www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,825400,00.html

THE LECTURE

Hear LTG Gavin predict in 1972 the condition of the world today!

VIDEO

www.youtube.com/watch?v=vsdRR5uOSnY

www.youtube.com/watch?v=vsdRR5uOSnY

www.youtube.com/watch?v=4-PDPS5oUFY

www.youtube.com/watch?v=4-PDPS5oUFY

www.youtube.com/watch?v=gvd_W_koDLk

www.youtube.com/watch?v=gvd_W_koDLk

AUDIO

www.library.ucsb.edu/speccoll

The Center for the Study of Democratic

Institutions Audio Archive

Program 569: Military Security Blankets

Army General James M. Gavin discusses his belief that the security of the United States no longer depends on weapons, armed forces, and holding areas of strategic value around the globe, but rather on less tangible factors such as the people's standard of living and the overall economic health of the nation. With Harry S. Ashmore, John Cogley, Sidney Holt, George McTurnan Kahin, Donald McDonald, and Robert Rosen. Mar. 10, 1972. [CSDI program number 569; UCSB tape number A8185/R7]

Listen: (28:30)

Download: Military Security Blankets (11.5 MB)

http://cylinders.library.ucsb.edu/audio/8000/a8185/cusb-a8185b.mp3

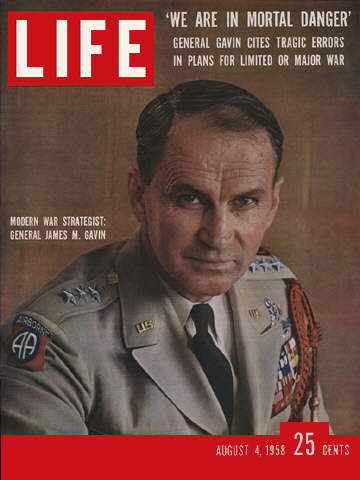

MAGAZINE ARTICLES

Atom-Age Army

TIME magazine, Monday, Aug. 11, 1958

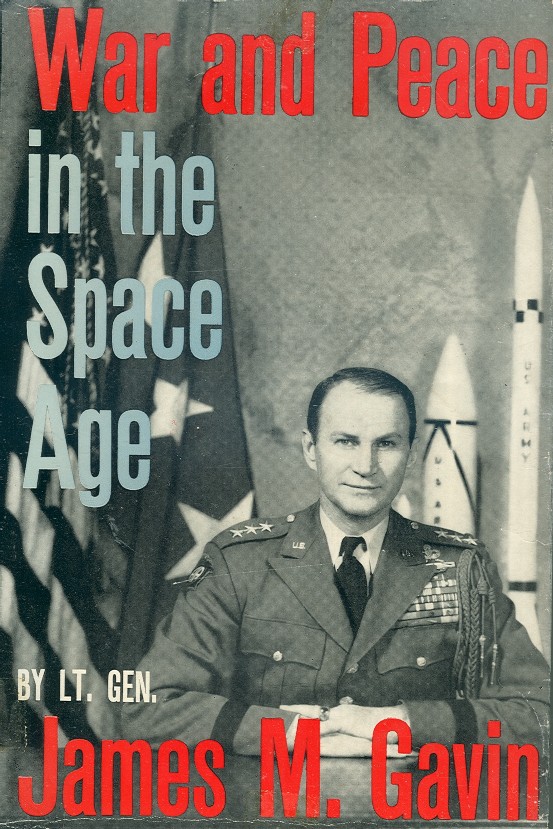

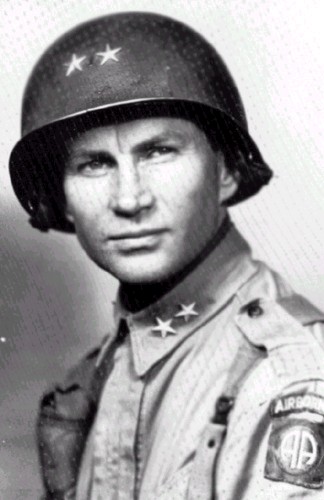

"I am not going out to write and raise a rumpus and things," said Lieut. General James M. ("Slim Jim") Gavin, 50, Army Research and Development chief, when he announced his retirement from the service seven months ago, after losing his battle to get a healthy boost in his 1959 budget (TIME, Jan. 13). This week LIFE published the second of two installments on Gavin's quickly written 304-page book, War and Peace in the Space Age (Harper; $5), a rumpus-raising attack on his old enemies and a sharp accusation that the Army is in bad shape technologically because the defense effort has been too concentrated on the Air Force. And this, he says, is doubly tragic, because:

1) limited wars using tactical atomic weapons are still more likely than the massive air-atomic one for which the Strategic Air Command is ready, and

2) SAC's big bombers will be useless in the missile age that is almost upon the world.

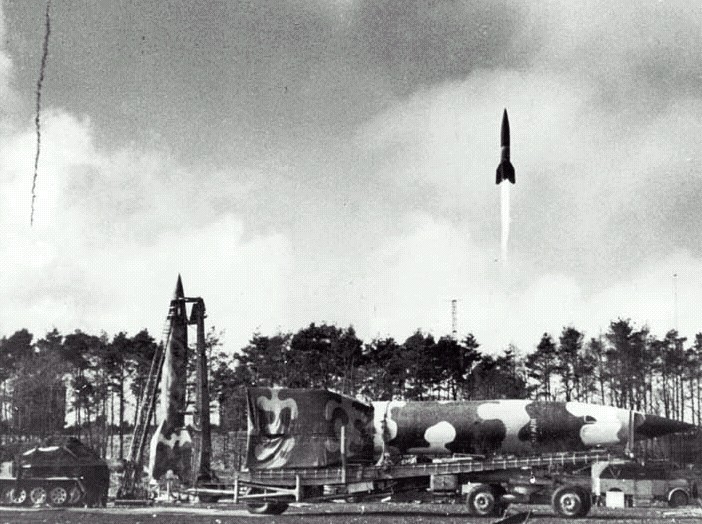

The manned atomic bomber, declares Paratrooper Gavin, will be out of business even before the intercontinental ballistic missile is on hand to replace it. Date for the bomber's "early obsolescence": the moment effective Russian "surface-to-air missiles carrying nuclear warheads are on the site in numbers." If such deterrent protection is to be retained, argues Gavin, "we will have to step up missile production so as to have, at an early date, an arsenal of combat-ready, mobile, intermediate and long-range missile systems."

Other targets at which Gavin fires:

EX-DEFENSE SECRETARY CHARLES E. WILSON.

Incompetent and corrupt Secretary of Defense Wilson

Gavin quotes an unnamed service chief on Wilson: "The most uninformed man, and the most determined to remain so." His "deception and duplicity," says Gavin, let him conceal slashes in combat-ready divisions by creating "Wilson" divisions out of paper groups of troops as far apart as Fort Benning, Ga. and the Panama Canal Zone. Wilson made good a foolish assurance to Congress that no additional Soldiers were needed for Formosan defense, charges Gavin, by shipping groups over without shoulder patches.*

U.S. INDUSTRY.

Industrial pressure, he charges, is partly responsible for "hundreds of millions of dollars being spent on obsolete weapons."

THE DEFENSE DEPARTMENT.

The Defense Department civil servants who, more permanent in the Pentagon than either politically appointed Secretaries or rotated military career officers, pervert the decision-making machinery. Though he does not name Defense Comptroller Wilfred J. McNeil, Gavin bombs the fiscal officer in the Pentagon who often rejects projects without understanding of military needs.

THE PRESIDENT OF THE U.S.

Dwight D. Eisenhower was "out of touch" with technological advances in weaponry, says Gavin, as far back as SHAPE days.

www.youtube.com/watch?v=mLzchVWGSrk

www.youtube.com/watch?v=mLzchVWGSrk

As Lieut. General James Gavin concluded his closed-door testimony before the Senate Preparedness Subcommittee one day last week, Chairman Lyndon Johnson scribbled out a press statement summarizing the testimony and handed it to Gavin. Old Soldier Gavin hurriedly looked it over and okayed it. With that began Round Two of the extraordinary story of Jim Gavin's proffered resignation from the U.S. Army (TIME, Jan. 13).

In the statement. Paratrooper Gavin, the two-fisted boss of the Army's Research and Development section, bluntly revealed his "intuitive" feeling that Army Chief of Staff Maxwell Taylor had reneged on an agreement to make him head of the U.S. Continental Army Command (with a fourth star for his shoulder). Furthermore, said Gavin, the Army had tried to transfer him to command of the U.S. Seventh Army in Europe (the same three stars), a step that was aimed at halting his ringing insistence that the Army's role was being whittled down.

"Genial Manager."

It was Lyndon Johnson's swift pencil that complicated the Gavin mess, since Gavin's fundamental reason for quitting-his failure to arouse sympathy for the Army's cause-was stuffed in at the end of the press statement. To make the mess messier, Army Secretary Wilber Brucker next day called a press conference to explain how it all started. Before Christmas, when Gavin sent word around that he planned to retire, Brucker called him into his office. "I urged General Gavin to be patient," explained Brucker in the tones of a genial office manager referring to his ambitious messenger boy. He appealed to Gavin to accept the Seventh Army job and a possible promotion a year later. Gavin refused.

The two bargained on, as Secretary Brucker told it, with West Pointer Gavin holding out for the Continental Army Command assignment, an anguished Brucker pleading that Gavin should at least stay on in his present job. At length Gavin promised to "reconsider," for despite his personal ambitions, he still felt strongly for the Army's cause.

Passionate Loser.

It dawned on Lyndon Johnson's subcommittee that Johnson's statements plus Brucker's account of bargaining with one of his generals over a duty assignment had indeed done an injustice to the record of a distinguished Soldier. Back to Capitol Hill next day went Jim Gavin for another run-through before the committee and another press statement. Said Gavin: "I can do better for the Army outside than in. I have no ax to grind. I am not unhappy with my Secretary. I am not going out to write and raise a rumpus and things."

With that, beribboned (two D.S.M.s, two D.S.C.s, a Silver Star) Slim Jim Gavin marched out of the hearing room, leaving behind, instead of a disturbing picture of an Army where high officials barter for stars, a picture of a passionate partisan who played the game and lost.

www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,936744,00.html

"Break up the Joint Chiefs"Monday, Dec. 23, 1957

As Chief of Staff, U.S. Army (1945-48), five-star General Dwight Eisenhower was one of the chief architects of the National Security Act of 1947, which set up the separate U.S. Air Force and was also designed-though with numerous compromises-to "unify" the armed services. As President of the U.S., Dwight Eisenhower has a better basic knowledge of how the services work than any President in modern history. Yet, paradoxically, one of the soft spots of his Administration record is that, during the regime of Defense Secretary Charlie Wilson, Ike let Pentagon administration get out of hand.

At his conference with legislative leaders last fortnight the President sat fuming while Congressmen asked sharp questions-and got limp answers from Pentagon officials-about interservice rivalries, overlapping missile programs and the whole organizational foul-up that makes it almost impossible to trace responsibility for any kind of failure in U.S. defense. No sooner had the congressional leaders left the White House than President Eisenhower called Defense Secretary Neil McElroy, into his office. His orders: find the right answers to the Pentagon's problems and put them into effect. Said the President: "You have a free hand."

More & Better.

It was not all that simple: before Neil McElroy could attack the Pentagon's problems he had first to know and understand them himself. And the same organizational tangle that brought on Ike's order is still working against McElroy-or his three subordinate service secretaries, or the 30 assistant and deputy secretaries-achieving the required knowledge and understanding. Never has that fact been more bluntly put than last week, when the Army's tough, brainy research and development chief, Lieut. General James M. Gavin, appeared before the Senate Preparedness Investigating Subcommittee.

Neil McElroy, said Paratrooper Gavin pointedly, is "the most able man who has come to that office [Secretary of Defense]." But McElroy needs more and better "professional military advice" than he has been able to get under the Pentagon system from the Joint Chiefs of Staff -or from assistant secretaries whose regimes, said Gavin, have lasted "somewhat on the order of a year and a half."

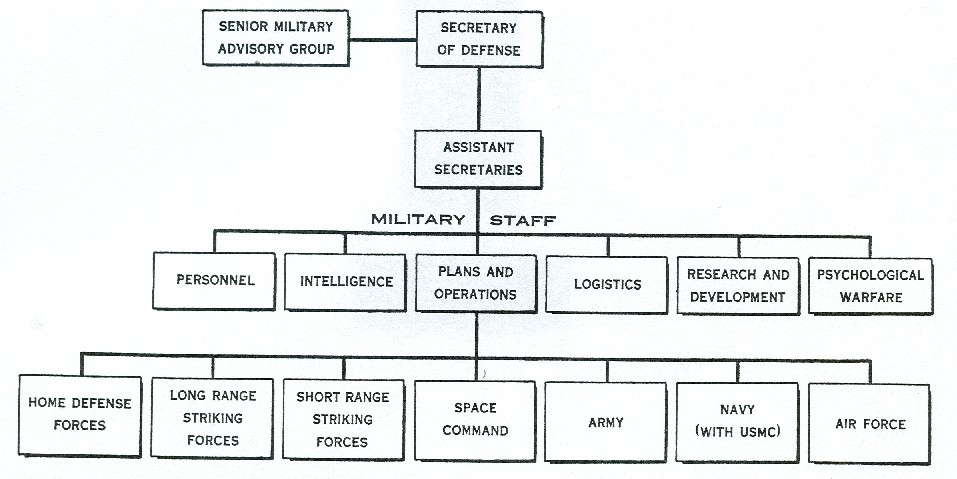

The Joint Chiefs of Staff is a sort of command-by-committee system (Gavin later emphasized that he was not talking about the individual competence of the present chiefs) and is not enough. Said Jim Gavin: "He [McElroy] needs more advice than the Joint Chiefs of Staff give him. I think really what is needed now is a competent military staff of senior military people working directly for the Secretary of Defense. I would have them take over the functions of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. I would have the military staff organized to handle operations, plans, intelligence, and in fact break up the Joint Chiefs of Staff."

Such a career staff, said General Gavin, should be drawn from all services, but should be "completely integrated across the board." Said Gavin: "The thing that disturbs a number of people, and I am included, is that there is no operational staff within the Department of Defense, and in the event of war it would have to be reorganized."

(2 of 2)

First Things First.

At no point did Gavin actually advocate a "general staff system"-which conjures up images of Prussianism to many a skittish Congressman-and to all devout Navymen. But that was precisely what he was urging, just as retired Air Force General James Doolittle had urged a fortnight before when appearing before the Preparedness Investigating Subcommittee. In the minds of Jim Gavin and Jimmy Doolittle, and in the opinion of others among the nation's best military thinkers, Neil McElroy cannot even begin to solve the Pentagon's problems until he has a general staff, whatever it may be called. Their argument: only a general staff, standing above violent service loyalties and ambitions, can work out a single, integrated, sensible U.S. defense plan. And only within the context of a single, integrated, sensible defense plan can Neil McElroy start using his free hand to tackle the subsidiary problems. Among them:

ROLES & MISSIONS.

If he is to head off an interservice blow-up that will make past squabbles seem like mere brush fires, McElroy must redefine obsolescent service roles and missions assignments (air to the Air Force, sea control to the Navy, land to the Army) in the light of missile strategy, to which old geographic concepts no longer apply. Outer space, by present definitions, belongs to no single service; neither does defense against enemy space missiles. Neither, for that matter, does the missile itself. All the services are rushing in with proposals, claims, bids.

ADMINISTRATION.

The Defense Department must find a way to become an operational as well as a policymaking body in such grey areas as missile development. McElroy has promised a single manager for new space programs. Another critical problem is the increasing demand for an effective missile "czar," since neither Missile Director William Holaday nor Presidential Science Adviser James Killian has yet fulfilled that role.

EXPENDITURES.

McElroy's predecessor, Charlie Wilson, let costs get so far out of hand that he was forced to call an abrupt halt to military procurement before the end of fiscal 1957. He also had to reduce procurement programs for 1958 to an extent that caused havoc in the airframe industry. McElroy will probably have about $2 billion more than Wilson to spend, will have that much bigger a problem in trying to control the spending.

LIMITED WAR v. GENERAL WAR.

During Wilson's regime, big-war thinking dominated U.S. military policy and procurements. But there is a rising clamor for the U.S. to prepare itself equally for small, limited wars; the Army especially is driving hard for the men and equipment, including airplanes; is already on the way to having an air force of its own.

In his brief time in office, Neil McElroy has indicated that he may be a strong Defense Secretary. He will have to be: his is the awesome job of making up for past mistakes while presiding over the orderly and economical phasing-in of an entire new military technology, without weakening U.S. forces in being.

www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,867921,00.html

"A Real Big Brawl"Monday, Nov. 11, 1957

Into Washington's Sheraton-Park Hotel last week crowded 2,000 delegates to the third annual meeting of the Association of the U.S. Army, a private organization made up of Army and ex-Army men and a loud-speaking outlet for top-level Army propaganda. On hand to stir them on were the Army's senior commanders, striving both by indirection and by extraordinarily blunt talk to overturn Defense Department policy and win for the Army a major place in the missile world. Displayed around the hotel ballroom were Army missiles and parts of missiles; at the entrance a placard blazoned the Army's basic doctrinal claim to render the Air Force obsolete. "In the missile era," read the placard, quoting the Army's Lieut. General James M. Gavin, "the man who controls the land will control the space above it."

Jupiter & Zeus.

Continental Army Command's General Willard G. Wyman contributed a stinging attack against the Defense Department's "arbitrary," "rigid" and "dangerous" ruling that Army missiles must be limited to 200 miles ground-to-ground and 100 miles ground-to-air (TIME, Dec. 10).

Short-Range Army Honest John Unguided Rocket

www.youtube.com/watch?v=cpJeyiDLPXA

The MGR-1 Honest John rocket was the first nuclear-capable surface-to-surface rocket in the US arsenal. Designated Artillery Rocket XM31, the first such rocket was tested in 1951 and deployed in January 1953. The designator was changed to M31 in September, 1953 and were deployed in Europe several months later. It is important to note that alternatively, the rocket was designed to be capable of carrying ordinary high-explosive warheads, even though that was not the primary purpose for which it was envisioned since it lacked guidance accuracy to make small warheads effective.

The M31 consisted of a truck-mounted, unguided, solid-fueled rocket transported in 3 separate parts. Before launch they were combined in the field, mounted on an M289 launcher and aimed and fired in about 5 minutes. The rocket was originally outfitted with a W7 dial-a-yield nuclear warhead with a yield of up to 20 kilotons and later a W31 warhead with a yield of up to 40 kt. It had a range between 5.5 km (3.4 miles) and 24.8 km (15.4 miles).

In the 1960s Sarin nerve gas cluster munitions were also available for Honest John launch.

There were 2 versions: * MGR-1A had a range of 48 kilometers, takeoff thrust of 400 kN, takeoff weight of 2720 kg, diameter of 580 mm and length of 8.32 m. * MGR-1B had a range of 37 kilometers, launch thrust of 382 kN, launch weight of 2040 kg, diameter of 760 mm and length of 7.56 m.

Production of the MGR-1 variants finished in 1965 with a total production run of more than 7,000 rockets. The system was replaced with the MGM-52 Lance missile in 1973, but was deployed with NATO units in Europe and U.S. Army National Guard units as late as 1982.

www.youtube.com/watch?v=V1GF2kii9Hk

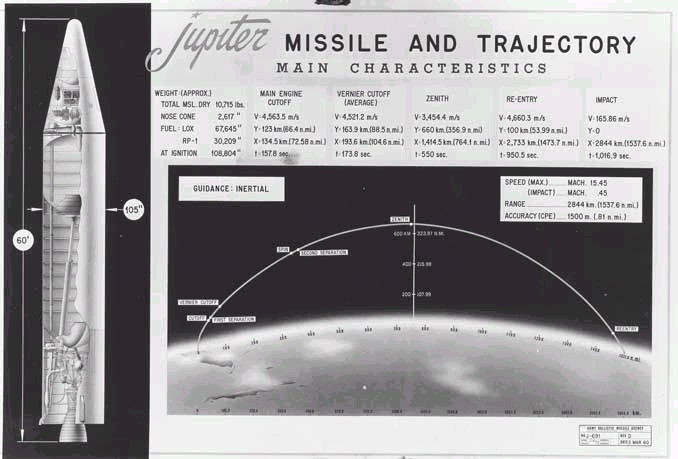

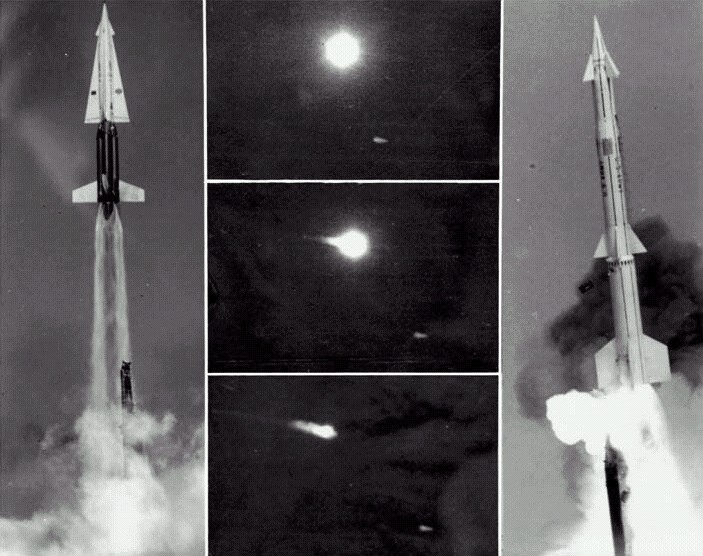

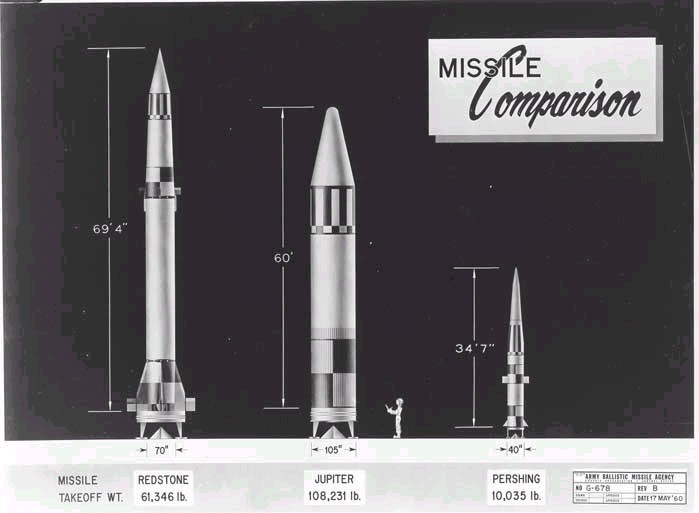

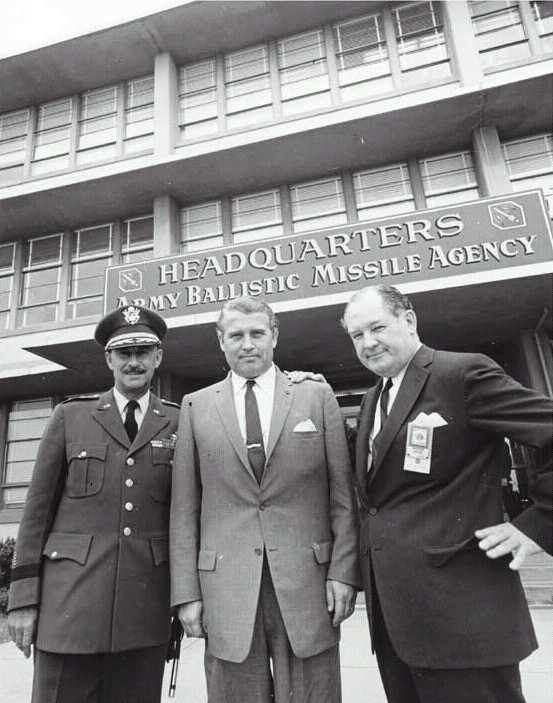

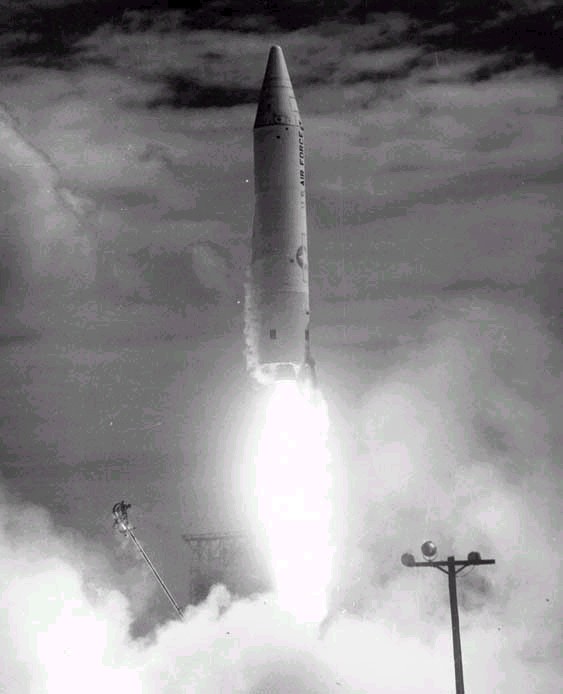

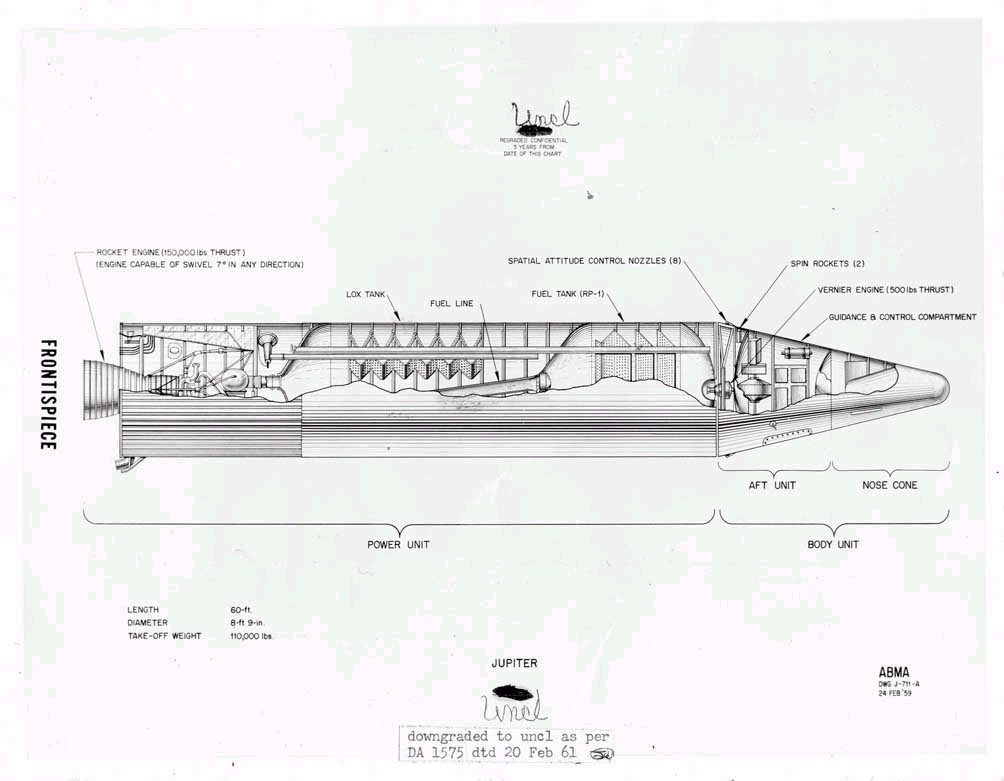

Army Secretary Wilber M. Brucker decorated the Redstone Arsenal's most famous missile scientist, ex-German Missileman Wernher von Braun, boosted the Army's claim that its 1,500-mile missile Jupiter is superior to the rival Air Force Thor and is in fact "the most advanced guided missile yet produced in the free world."

www.youtube.com/watch?v=ULeMVjbsKb8

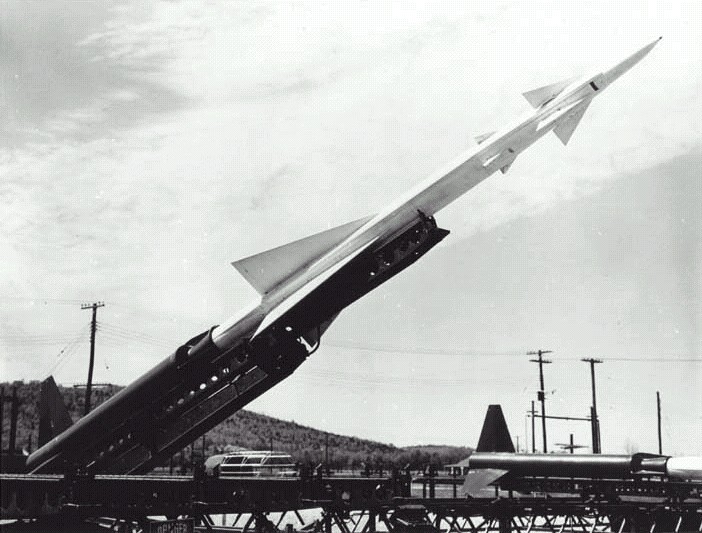

Army Chief of Staff General Maxwell Taylor staked Army's claim to the next but faraway great step in weaponry, the defensive missile system to stop the attacking missile. He plugged hard for an Army project called Nike Zeus-"which already partially exists in the form of research-and-development components"-as the basis for an anti-missile missile program, thus by inference downgrading the rival Air Force Wizard anti-missile project (as well as an Air Force Pentagon-corridor campaign to put the Army out of the defensive antiaircraft missile business altogether).

Most strident Army performance of the week came from Lieut. General Stanley Mickelson, retiring chief of Army's Air Defense Command. So sharp was Mickelson's original speech that the Defense Department would not let him deliver all of it; the draft, however, had already been distributed to newsmen. Bitterly, the Mickelson text scorned the Air Force, derided the concept of airpower. Said the Army's General Mickelson, echoing a favorite line of the Army's General Gavin: "The Army points the way for America to shed herself of any stigma of the theory of mass destruction of civilian populations."

"Those Bastards."

Meanwhile, back at the Pentagon, the Air Force contingent was under direct orders to keep cool and dignified, to blow-off only in private. "Those bastards," said one high Air Force officer in private, "can't win in the Joint Chiefs of Staff, where they ought to take their case, so they went to the public. They're not going to get away with it. It isn't going to do them any good. It's going to be a real big brawl."

All in all, in a time of national crisis, it was quite a week for interservice rivalry. And quite a warning to the Commander in Chief that appointment of a tough, top boss for the missile program could not be long delayed.

www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,825005,00.html

Let the Army ...

Monday, Jun. 24, 1957

The failure of the first Air Force test Atlas gave underdog Army spokesmen new confidence in the bitter interservice fracas on U.S. missile dominance. Against Atlas's crash and the Air Force's bug-ridden 1,500-mile Thor missile, the Army touted its own relatively successful 1,500-mile Jupiter (TIME, June 10) and the new low-level-surface-to-air Hawk, made its boldest pitch yet for operational control of intermediate-range missilery (1,500 miles) now assigned to the Air Force.

Hawk SAM on all-terrain tracked carrier

Chief architect of the new approach is tough Lieut. General James M. Gavin, Army Research and Development boss, who before a Senate Appropriations Subcommittee last week flung a basic reverse-twist challenge to Air Force doctrine: "In the missile era, the man who controls the land will control the space above it. The control of land areas [rather than air] will be decisive." In effect, ex-Paratrooper Gavin was arguing that the Army, instead of the Air Force, should be assigned to the area defense (as well as point defense) of the U.S. against Soviet ICBM attack. The Army, said Gavin, is better oriented for the air-defense job of the future: "We want 100% air defense and we consider this attainable. There has been no schizophrenia in the Army about how to get an air defense. We haven't worried about [jet] interceptors. We have gone after missiles . . . Very little, if anything, is going to get through us."

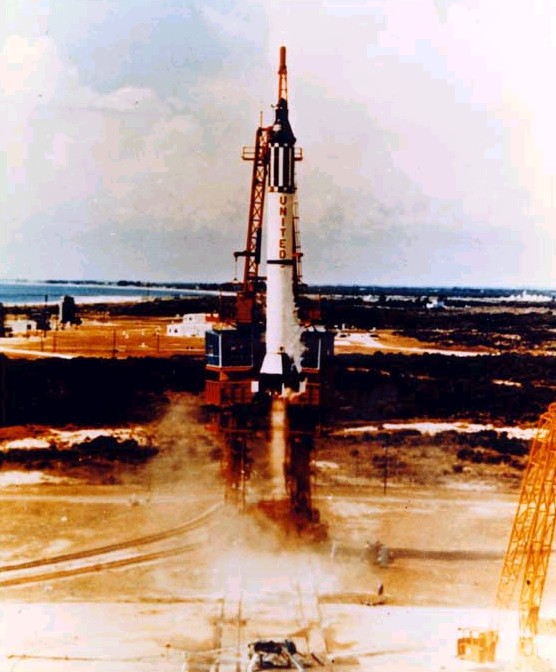

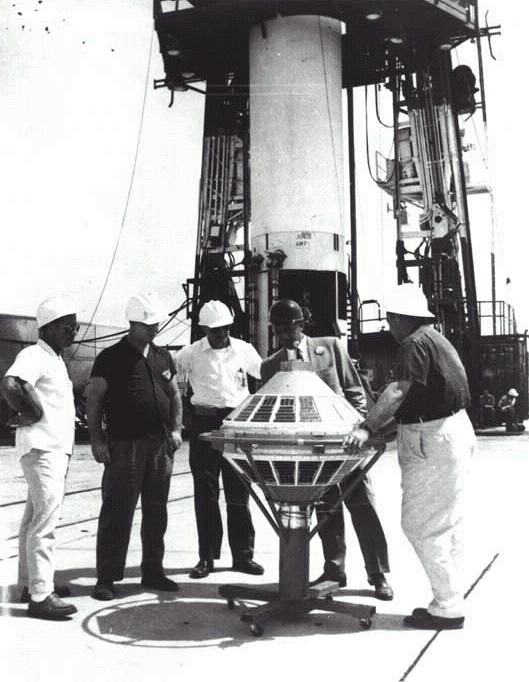

U.S. Army got America into Space, NOT NASA: First American Satellite in Orbit but could have beat the Russians had DoD Not Interfered, Army rockets put first American astronauts into space

www.redstone.army.mil/history/systems/redstone/welcome.html

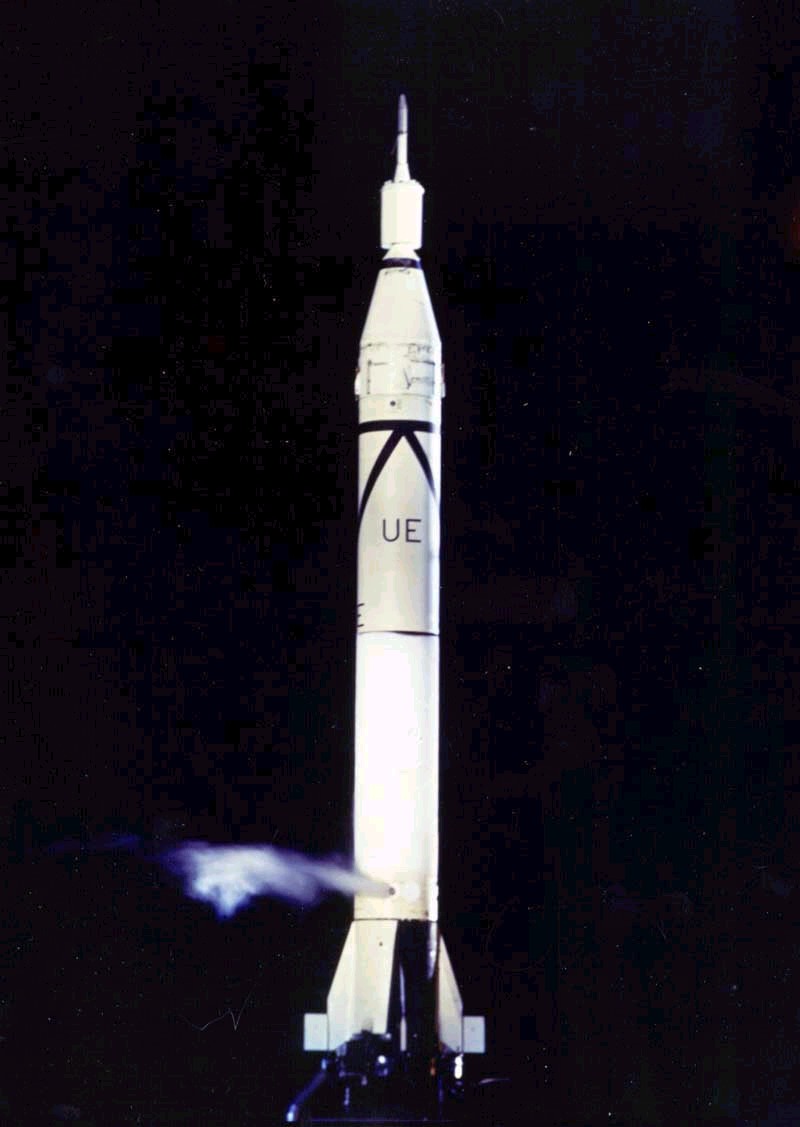

On 10 July 1951, the Office, Chief of Ordnance (OCO) formally transferred research and development responsibility for the REDSTONE project to Redstone Arsenal. The OCO officially assigned the REDSTONE missile its name on 8 April 1952. Also known as the Army's "Old Reliable," the REDSTONE was a highly accurate, liquid propelled, surface-to-surface missile capable of transporting nuclear or conventional warheads against targets at ranges up to approximately 200 miles. First deployed in 1958, the REDSTONE was the forerunner of the JUPITER missile. On 31 January 1958, the REDSTONE was used as the first stage in the launch vehicle used by the Army to orbit the EXPLORER I, the Free World's first scientific earth satellite. A modified REDSTONE carried CDR Alan B. Shepard, Jr. on his historic suborbital flight on 5 May 1961.

PROJECT "Mercury 7" Astronauts at Redstone Arsenal Meeting before Launches

With the deployment of the speedier, more mobile [smaller, solid-fuel] PERSHING missile system in 1964, the REDSTONE missile system was ceremonially retired at Redstone Arsenal on 30 October 1964.

www.youtube.com/watch?v=x7YABPisFGE

www.youtube.com/watch?v=x7YABPisFGE

http:// www.youtube.com/watch?v=1ba2KS3_FY0

www.youtube.com/watch?v=1ba2KS3_FY0

Pershing was a family of solid-fueled two-stage medium-range ballistic missiles designed and built by Martin Marietta to replace the Redstone missile as the United States Army's primary theater-level weapon. It was named for General of the Armies (6-Stars) John J. Pershing. The systems were managed by the U.S. Army Missile Command (MICOM) and deployed by the United States Army Field Artillery Corps.

Pershing IA

In 1964, a series of operational tests and follow-on tests were performed to determine the reliability of the Pershing 1. The Secretary of Defense then requested that the Army define the modifications required to make Pershing suitable for the quick reaction alert (QRA) role. The Pershing 1A development program was approved in 1965, and the original Pershing was renamed to Pershing I. Martin Marietta received the Pershing 1A production contract in mid-1967. The 2nd Battalion, 44th Field Artillery received equipment at Fort Sill in 1969. Project SWAP replaced all of the Pershing equipment in Germany by mid-1970 and the first units quickly achieved QRA status.

Pershing 1A was a "quick reaction alert" system and so had faster vehicles, launch times and newer electronics. The total number of launchers was increased from eight to 36 per battalion. It was deployed from May 1969 and by 1970 almost all the Pershing I systems had been upgraded to Pershing IA under Project SWAP. Production of the Pershing IA ended in 1975 and reopened in 1977 to replace missiles expended in training. In the mid-1970s the Pershing 1A system was further improved to allow the firing of a platoon's three missiles in quick succession and from any site without the need for surveying. 754 Pershing I/IA missiles were built with 180 deployed in Europe.[8]

The battalions in Europe were reorganized under new tables of organization and equipment (TOE); an infantry battalion was authorized and formed to provide additional security for the system; and, the 56th Artillery Group was reorganized and redesignated the 56th Field Artillery Brigade. Due to the nature of the weapon system, officer positions were increased by one grade: batteries were commanded by a major instead of a captain; battalions were commanded by a colonel and the brigade was commanded by a brigadier general.

The erector launcher (EL) was a modified low-boy flat-bed trailer towed by a Ford M757 5-ton tractor. The erection booms used a 3,000 psi pneumatic over hydraulic system that could erect the 5 ton missile from horizontal to vertical in nine seconds. The PTS and PS were mounted on a Ford M656 tractor. Launch activation was performed from a remote fire box that could be deployed locally or mounted in the battery control central (BCC). One PTS controlled three launchers-- when one launch count was complete, ten large cables were moved to the next launcher.

A repackaging effort of the missile and power station was completed in 1974 to provide easier access to missile components, reduce maintenance, and improve reliability. A new digital guidance and control computer combined the functions of the analog control computer and the analog guidance computer into one package. The mean corrective maintenance time was decreased from 8.7 hours to a requirement of 3.8 hours. The reliability increased from 32 hours mean time between failures to a requirement of 65 hours. In 1976, the sequential launch adapter (SLA) and the automatic reference system (ARS) were introduced. The SLA was an automatic switching device mounted in a 10 trailer that allowed the PTS to remain connected to all three launchers. This allowed all three launchers to remain "hot" and greatly decreasing the time between launches. The ARS eliminated the theodolites previously used to lay and orient the missile. It included a north seeking gyro and a laser link to the ST-120 in the missile. Once the ARS was set up, a cold missile could be oriented in a much shorter time.

MILESTONES

20 November '44 Ordnance Department entered into a research and development contract with the General Electric Company for study and development of long-range missiles that could be used against ground targets and high-altitude aircraft. This was the beginning of the HERMES project.

June '46 General Electric began a feasibility study of the HERMES Cl which later formed the basis for early REDSTONE missile research.

1 June 49 Redstone Arsenal was reactivated from standby status as the site of the Ordnance Rocket Center.

28 October '49 The Secretary of the Army approved the transfer of the Ordnance Research and Development Division, Sub-Office (Rocket) at Fort Bliss, Texas, to Redstone Arsenal. Among those transferred were Dr. Wernher von Braun and his team of German scientists and technicians who had come to the United States under "Operation Paperclip" during 1945 and 1946.

15 April '50 After its transfer to Redstone Arsenal, the aforementioned sub-office was redesignated the Ordnance Guided Missile Center.

10 July '50 Office, Chief of Ordnance directed that the Ordnance Guided Missile Center conduct a preliminary study of the technical requirements and possibilities of developing a 500-mile tactical missile that would be used principally in providing support for the operations of the Army Field Forces. 11 September 50 Ordnance Department directed that the HERMES contract with General Electric Company be amended to transfer responsibility for the HERMES Cl project to the Ordnance Guided Missile Center.

10 July '51 The Office, Chief of Ordnance formally transferred the responsibility for conducting the research and development phase of the HERMES Cl project to Redstone Arsenal

1 April '52 The Office, Chief of Ordnance (OCO) disapproved Redstone Arsenal's proposed development plan for what would become the REDSTONE missile. The arsenal had intended to implement the manufacturing program for these missiles by creating an assembly line in its own development shops. The OCO, however, required that the development effort be done by a prime contractor. Nonetheless, delays in the acquisition of production facilities for the prime contractor caused Redstone Arsenal to fabricate and assemble the first 12 REDSTONE missiles along with missiles 18 through 29.

8 April '52 The REDSTONE missile system officially received its popular name. Previously, this missile was known at various times and places as the HERMES Cl, MAJOR, URSA, XSSM-G-14, and XSSM-A-14.

October '52 Chrysler Corporation issued a letter order contract to proceed with active work as the prime contractor on the REDSTONE missile system. This contract was definitized on 19 June 53.

20 August '53 The first REDSTONE research and development missile was flight tested.

15 June '55 Chrysler Corporation received the first industrial contract for the REDSTONE.

1 February '56 Responsibility for prosecuting the REDSTONE program was transferred from Redstone Arsenal to the newly activated Army Ballistic Missile Agency (ABMA).

15 April '56 The first REDSTONE missile battalion, the 217th Field Artillery Missile Battalion, was formally activated at Redstone Arsenal.

19 July '56 The first REDSTONE missile to be fabricated and assembled by Chrysler Corporation was flight tested.

20 September '56 JUPITER-C Missile RS-27, a modified REDSTONE, achieved the first deep penetration of space with an altitude of more than 680 miles and a range of over 3,300 miles.

8 August '57 JUPITER-C Missile RS-40 a modified REDSTONE, was successfully launched. Its nose cone was the first to be recovered from outer space. The nose cone carried the first missile mail ever delivered over intermediate range ballistic missile (IRBM) range.

9 September '57 The 40th Field Artillery Missile Group, the first heavy missile group organized in the U.S. Army, was transferred from Fort Carson, Colorado, to Redstone Arsenal.

2 October '57 The first REDSTONE missile firing in which troops actually participated occurred.

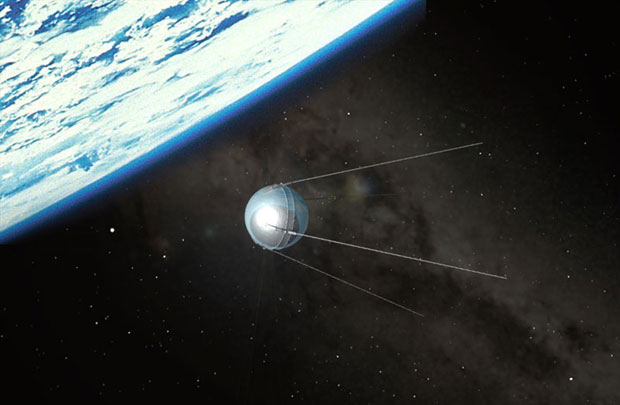

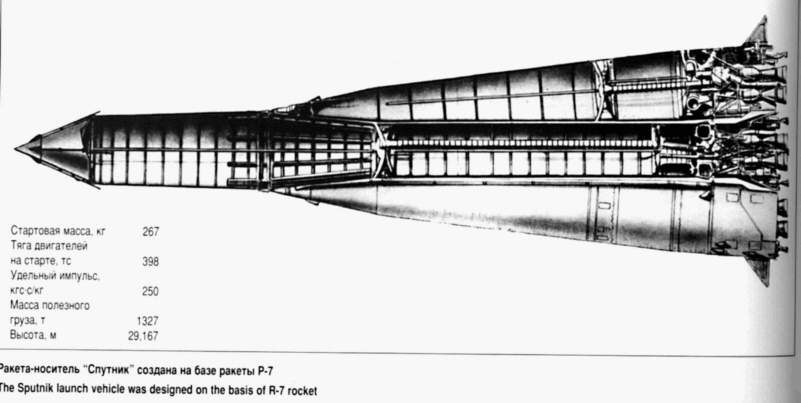

4 October '57 The U.S.S.R. launched SPUTNIK I.

8 November '57 The Secretary of Defense directed that DA modify two JUPITER-C missiles (modified REDSTONEs) and attempt to place an artificial earth satellite in orbit by March 58.

31 January '58 ABMA successfully launched JUPITER-C Missile RS-29, a modified REDSTONE, which placed EXPLORER I--the first U.S. satellite--into earth orbit.

16 May '58 The first successful troop launching of a tactical REDSTONE missile occurred at Cape Canaveral , Florida.

June '58 The REDSTONE became the first large U.S. ballistic missile to be deployed overseas, joining the NATO Shield Force.

2 June '58 The first overland firing of a large U.S. ballistic missile by combat troops occurred. A REDSTONE was successfully launched by the 40th Field Artillery Missile Group (Heavy) at White Sands Missile Range.

31 July '58 A REDSTONE missile was fired to an altitude in excess of 200,000 feet and a nuclear device of a megaton was detonated. This was the first such accomplishment by the United States.

24 October '58 The REDSTONE underwent static firing at White Sands Missile Range, the first time such a test had been conducted there.

November '58 The last REDSTONE research and development missile was flight tested. Of the 37 missiles flight tested for research and development purposes, 27 were successfully launched.

16 January '59 NASA issued a request to ABMA for eight REDSTONE missiles to be used in PROJECT MERCURY.

15 March '60 A REDSTONE missile successfully fired from White Sands Missile Range lofted a "flying TV station" for the first time.

10 June '60 The REDSTONE missile was launched over the largest trajectory ever attempted over land (120 miles).

19 December '60 MERCURY-REDSTONE 1 (MR-1) was successfully launched, proving the system's operational capabilities in a space environment.

31 January '61 The second MERCURY-REDSTONE (MR-2) test flight carried a chimpanzee named Ham into space.

5 May '61 MERCURY-REDSTONE 3 (MR-3) carried Commander Alan B. Shepard, Jr., on his historic suborbital flight.

21 July '61 The last MERCURY-REDSTONE flight carried Captain Virgil I. Grissom to a peak altitude of 118 miles and safely landed him 303 miles downrange.

25 June '64 The REDSTONE missile was classified as obsolete.

30 October 64 In a ceremony on the parade field at Redstone Arsenal, the REDSTONE missile was ceremonially retired.

December '64 The initial REDSTONE production contract awarded to Chrysler in October 52 was closed out.

www.redstone.army.mil/history/explorer/explorer.html

Dr. Ernst Stuhlinger of the Army Ballistic Missile Agency revealed in a speech at the Army Science Symposium at the United States Military Academy, West Point, New York, during July 1957 that practically all components necessary for a successful satellite launch were available at the Army Ballistic Missile Agency. These components, he said, were left from the earlier Project Orbiter and were also available from the Jupiter-C reentry test vehicle program. He also indicated that the Army Ballistic Missile Agency had an orbit evaluation program, first projected by the Guided Missile Development Division in 1954. It consisted of a computer program that would provide scientific data on the oblateness of the earth, on the density of the upper atmosphere, and on high altitude ionization.

Among other things Dr. Stuhlinger noted in his speech was his observation that the 300-pound payload of the Jupiter-C reentry test vehicle missile could be converted to a fourth rocket stage plus an artificial earth satellite. In stating that the projected program had also included studies on high atmospheric conditions, on ionized layers of great altitudes, on the lifetime of satellites, on the earth's field of gravity, on mathematical studies of orbiting satellites, on recovery gear, on protective coverings for nose cones, and on radio-tracking and telemetering equipment (such as the highly sensitive micro-lock, a small continuous wave-radio transmitter developed by the Jet Propulsion Laboratories for Project Orbiter), Dr. Stuhlinger added strength to the rumors, rife at that time, that the Department of the Army was engaged in an unauthorized satellite project. Because of these rumors, the Secretary of Defense ordered the Department of the Army to refrain from any space activity. Following this, the Department reaffirmed its close cooperation with Project Vanguard and denied that any of its research programs interfered with the intended tactical uses of the Redstone.

Then, the Soviet Union launched Sputnik I on 4 October 1957. A month later, the Soviet Union orbited a second, larger satellite. In this country, Project Vanguard faltered when it experienced repeated failures- The Secretary of the Army then submitted a proposal for a satellite program to the Secretary of Defense [Wilson] during October. He pointed out that eight Jupiter-C missiles were available and with slight modification would be capable of launching artificial satellites. He suggested that the Department of the Army be authorized to pursue a 3-phase satellite program using these Jupiter-C missiles. The first phase of the proposed program provided for launching two Jupiter-C missiles in which the nose cone would be replaced by a fourth stage containing instrumentation that would be packaged in a cylindrical container-the satellite. In the second phase of the proposed program, the Army would launch five of the Jupiter-C missiles that would orbit satellites equipped with television facilities. The third and last phase of the proposed program also involved the launching of a Jupiter-C. In it, the nose cone would be replaced by a 300-pound surveillance satellite.

On 8 November 1957, the Secretary of Defense directed the Department of the Army to modify two Jupiter-C missiles and to attempt to place an artificial earth satellite in orbit by March 1958.

Eighty-four days later, on 31 January 1958, the Army Ballistic Missile Agency (ABMA) launched the first U.S. satellite-Explorer I-into orbit.

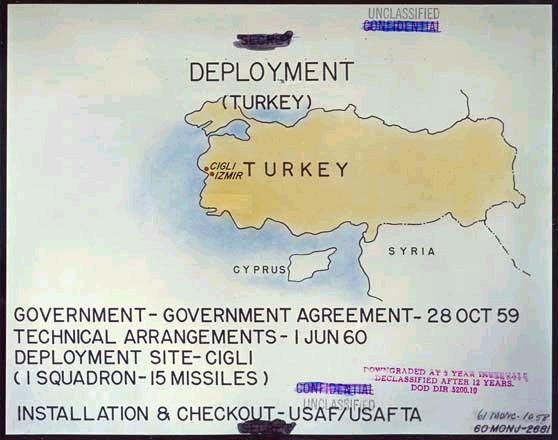

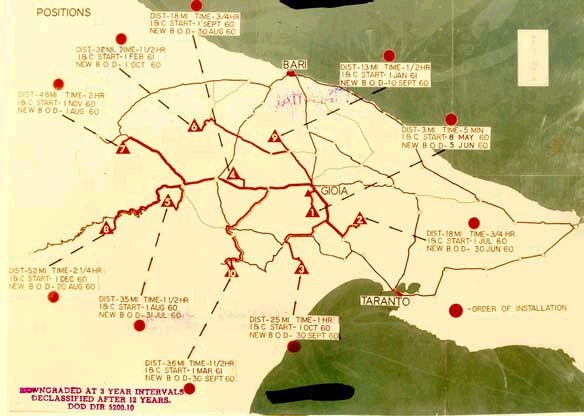

And it was the U.S. ARMY's IRBMs that were deployed first overseas with nuclear-warheads to smother any idea of the Soviets invading and taking over Europe. It was U.S. ARMY Jupiter IRBMs that deployed to Turkey and Italy (in stupid fixed sites by the moronic pampered USAF instead of the tactically sound mobile means designed by the Army) that were there as bargaining chips to get the Soviets to back down and take their IRBMs out of Cuba, preventing the world from being drawn into World War III.

Had it not been for the U.S. ARMY been ready in both conventional and nuclear forces despite the efforts of Secretary of Defense Wilson and Ike's disastrous "New Look" policies, we would have not just lost Korea, we would have had only USAF massive retaliation nuclear bombers to counter Soviet aggression, and if used we probably wouldn't even be here today.

Two months after retiring as the U.S. Army's Director on Research and Development, Lieutenant General James M. Gavin delivered his own atomic bombshell in response to setbacks in Korea, Hungary and the Soviets beating us into space with the Sputnik satellites; the masterpiece War & Peace in the Space Age. Mrs. Jean Gavin tells me that he dropped everything else he was doing in early 1958 and wrote the book from sun up to sun down, as a devoted Army wife she finally got to a chance to work on her golf game. Frustrated that America's defense was being thwarted by institutionalized complacency, General Gavin had had enough of suffering in silence and decided it was time to blow-the-whistle with an immediate after action review (AAR) on the battles going on within the newly formed but flawed Department of Defense (DoD) in order to save the day and find a way to win. This was the trademark of Gavin all through his life as a situational leader--- fighting for his family, his Paratroopers, his army and his citizens; a struggle to assess the situation and meet immediate demands, then learning how to get ahead and stay ahead by daring to change the situation and stack-the-deck in our favor.

Historical Significance

Without Gavin's book, America's post-WW2 defense establishment cannot be understood.

Gavin was there when DoD was born in 1947 and fought for its first decade to not fall into a defeatist, institutionalized rut that its still in today. We got lucky because the Soviet Union imploded economically in 1989, but that luck was engineered because just enough of Gavin's ideas were adopted after he had left the scene to prevent a take-over of Europe---of course no credit was given to him for this since he dared reveal the Pentagon's "dirty laundry" to the light of public scrutiny. Gavin's unselfishness to do what it took to force DoD to change was a gamble that saved America and the free world but at the cost of him becoming Secretary of Defense. The book is a blueprint for reforming DoD and was an obvious prima facie case for Gavin to be the next administration's SecDef to reform that organization into what is should be and still needs to be.

Gavin reveals the startling revelation that the U.S. Army had wanted to and had the ability to launch the first satellite into space long before the Russians did it but DoD civilian mandarins and the ruling U.S. Navy Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff did not want the Army to get the money and the glory so America as a whole suffered a severe strategic defeat. When America finally did put a satellite into orbit, it was on an Army rocket. When it put a man into space, it was on an Army rocket. The U.S. Army created America's ballistic missiles yet DoD ran by the USAF mafia took this role/mission away and gave the fruit of the Army's labor to the USAF when they finally admitted their manned heavy bombers might not get through to reach the Soviet Union in an all-out nuclear war. John S. Brown writes in the September 2006 issue of Army magazine:

"Revolts" against civilian superiors by generals and admirals have been infrequent, and rarely have gone well or accomplished much. An exception lies in the resignations of Generals Matthew Ridgway, Maxwell Taylor and James Gavin to protest the Eisenhower administration's "New look," which threatened to gut the Army and rely upon strategic weapons alone to keep the peace. Each of these three wrote a thoughtful book-Soldier: The Memoirs of Matthew B. Ridgway; The Uncertain Trumpet; and War and Peace in the Space Age, respectively-outlining their visions of what the defense paradigm should look like. Collectively considered, these became the basis for the full spectrum "flexible response" that served us so well through the rest of the Cold War.

"Flexible Response" to prevent Eisenhower/Nixon republican disasters after Korea, namely Indochina, Suez, Hungary, Lebanon, Quemoy, Tibet and Laos based on a non-working nuclear doomsday deterrent propelled JFK to the White House. General Taylor became his confidant and Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff but Ridgway remained in retirement.

Gavin Paid a Heavy Price for Writing the Book

Why didn't President John F. Kennedy appoint Gavin to be SecDef but instead made him Ambassador to France?

The answer, I believe is this book scared many influential people with its many sound but drastic ideas, threatening their military, industrial, congressional and think-tank (MICC-TT) rackets. If Gavin were SecDef, he'd turn the Pentagon around from a bloated, financially wasteful boondoggle back into a lean, efficient and effective Department of War---and this scared the socks off an America weary of the sacrifices of WW2 and who wanted to get back to the suburbs with the G.I. educational bill, work and making babies. The air force's siren's song was (and still is) that if America just paid for big, heavy bombers that could drop nuclear weapons on the enemy's civilian cities (allegedly "Strategic" Bombing), we'd scare all potential enemies to leave the baby boomers alone by this threat of mutually assured suicide. All the monies saved by not having to pay for amies and navies--just air forces---could go instead to paving inter-state highways, shopping malls and schools for the suburbanites. The problem is that don't-attack-or-else-I-will commit-suicide is an empty bluff as we surely would not kill ourselves for other countries and it doesn't stop the enemy from attacking with non-nuclear means as the "asymmetric" aggressions on South Korea in 1950 and Hungary in 1956 proved. Gavin's first sin was to call for more expenditures to field a flexible, small wars force to fight these "limited" wars when the MICC-TT racketeers only wanted to waste billions on "general wars" aka mythical WWIIIs that would be somehow prevented by threat of East-West national suicides. DoD wanted to spend, spend and spend on its mythological wars while ignoring the actual wars raging in the present. Does this sound vaguely familiar?

In 20-20 hindsight, what spoiled Gavin's chances for SecDef more than even daring to spend monies on the army and navy for small wars less than WWIII, was the "N" word---NUCLEAR.

People are scared to death of nuclear weapons.

Nuclear = death = certainly.

Ending of the 1965 movie, Dr. Strangelove

www.youtube.com/watch?v=-gb0mxcpPOU

www.youtube.com/watch?v=-gb0mxcpPOU

In contrast, Gavin, the great humanitarian, first wants wars to take place on BATTLEFIELDS not against civilians in cities. Next, to close-the-door to Soviet asymmetric attacks exploiting our unreadiness to fight on battlefields he sees small, air burst nuclear weapons as the certainty-of-death provider that coupled with early guidance means can even the odds in our favor if the communists---who can crack the whip on their population gang up on the west with superior numbers of men, tanks, airplanes and ships. If all possible doors of aggression are closed, Gavin instructs us that this means tactical violence can be avoided, we can attain our goals by not fighting which is the aim of sound STRATEGY. To do this, Gavin wants small, tactical nukes on everything; nuclear surface-to-air missiles to clear the skies of Soviet aircraft and incoming ballistic missiles, nuclear bazookas to wipe out Soviet tank formations, mobile, nuclear ballistic missiles to demolish their command and control, supplies and reserves and to even drop into the water to erase missile-firing submarines threatening the American homeland. He wants small nukes to be the "kentucky windage" to take up the slack for any missile guidance imprecision to get a sure effect, and in terms of anti-ballistic missile defense it still is the only "Star Wars" defense that we know will work, the American public was and still is not willing to accept the radiation to avoid blast and heat deaths. This is simply too many nukes in too many places for the American public to accept however desirable from a military point of view, so Gavin was too radical in the eyes of the JFK administration that wanted to bean count with Harvard Business theory men like Robert MacNamara, and we all know the disaster this brought on a few years later in Vietnam.

As Gavin left the service, small, mobile tactical nuclear ballistic missiles were indeed fielded by the U.S. Army into Europe and many have come to the conclusion that these were the things that actually prevented the Soviets from swarming through Fulda Gap; vindicating his vision just enough and long enough for the wall to go down.

Book Not Understood

The next question is, why was this booked ignored by the general public though highly influential in the inner circles of the Pentagon and the Washington beltway?

How many ideas (concepts) can you hold in your head at one time?

The majority of the human beings in the world are LINEAR, thinkers. They can only hold 1 idea in their head at any time and this makes them easily steered by the unscrupulous to do their bidding. Not thinking and having blinders on, brings on a certain type of complacent comfort even if it means certain death arriving after living an unfulfilled life. At the time of Gavin's youth, President Teddy Roosevelt saw this coming and secured major American land areas from urbanization in order to challenge ourselves so machines are misdirected into subsidizing too much comfort and convenience.

Gavin, a man who welcomed challenges, who welcomed problems---could hold many ideas in his head at the same time as a NON-LINEAR thinker. A problem that defies an easy, singular solution that requires multiple solutions does not depress Gavin, he wades into the situation and starts shooting "bad guys" with innovative means, assembling a PATTERN for success. Clearly, Gavin had read British General Francis Tucker's book, The Pattern of War and adopted his concept that wars can be seen as having distinct personalities if one can stand back and objectively fathom the many ideas at work and sort them out. War and Peace in the Space Age is clearly Gavin sorting out for the reader the current and future pattern of war---IF---and this is a big IF---the reader can keep several ideas in his head simultaneously. If he cannot, the book will scare the living feces out of him or her. Too complicated and too terrifying. Gavin realizes that war has indeed gotten far too complex and points out that having civilians without ANY military experience running DoD is a fatal error and events since 1958 grow in tragic intensity highlighting this systemic disease that must be corrected.

One way the linear dismiss the book is by wrongly concluding that its "dated" because Gavin uses nuclear weapons on many of his innovative war means and the book's title "Space Age" is too happy 1950s-ish. The facts are that Gavin only uses nukes to compensate for early guidance means lacking pinpoint impact into their targets, a situation not true today thanks to microprocessor chips (computers). Every time you read the word "nuclear" in Gavin's book, replace it with "precision guided warhead" unless some large area explosive effect is needed and you will quickly see that his book is spot-on in relevancy and prescient in its dire warnings for today and in the future. This concept book should be re-printed perhaps with a new title, "War and Peace in the Guided Missile Age" and made required reading for every officer and NCO in the U.S. military.

To my surprise, the book after the initial warning morphs into a mini-autobiography where Gavin reveals how he came to be the over-achieving and unsung superhero of the 20th century, working behind the scenes on our behalf. War and Peace in the Space Age is actually an autobiography-concept book.

Part 1 Autobiography: The Man

Gavin gets it. The enemy is death and death is hastened by COMPLACENCY. If you stay still, you stop growing. You stop, you die. True in life as in war. To live you have to keep moving, to keep growing and challenging yourself. Born in 1907 to two Irish-American parents who had just gambled everything to come over from Europe, he was orphaned at the age of two. The pioneer spirit of his parents was not in vain, as he was adopted by the Gavin Irish-American family in Pennsylvania. However, as he grew up in a harsh and strict environment he soon learned that America in the 1910s had stopped expanding westward and in his area had settled into a deadly complacency mining coal. The lack of mobility in thought and life from the crowded cities of the old world of Europe had returned. Gavin fought against it even at an early age. He sold newspapers everywhere and anywhere, he worked at a barbershop, he ran a gas station when the industrial age brought on the automobile. On his time off, Gavin marched himself over the next mountain to see what the countryside of his part of the earth offered in natural beauty. He finds books in an old church and reads every one. Yet, filled with all of these possibilities, when he returned on foot back to his coal-mining town, he simply could not get ahead within the narrow parameters there to improve the lot of his family or even get a high school education past grade school. In an amazing act of wisdom and courage, Gavin realized at 17 years old that no amount of stay-in-your-lane struggle (what we call "FIDO" in the Army) would achieve victory and decided like his parents to risk it all and move to New York City with only a few dollars in his pocket to find and if necessary make a winning situation, to Get It and Drive On (GIDO).

Saving the Gavins

First thing Gavin does in New York is to illegally enlist under-age into the Army. This is an important case illustrating how society can set up rackets which outsiders cannot win. Underage, Gavin would need his step parent's permission to join the Army and he candidly reveals that they would not support him in this with a mere signature because it would mean tacit admission that their complacent lifestyle in coal country was lacking. Don't get me wrong, America needs coal. However, it doesn't need coal at the cost of destroying the lives of the miners needed to get it. You could say Gavin should have waited another year til he was 18, but to say this would to show a lack of empathy and understanding for people locked into no-win situations. That's not how the human spirit and life works. There is no guarantee that in a year Gavin would have still had the courage or opportunity to reinvent himself by fleeing to New York City. You could say, "of course Gavin would have had the courage a year later". You will read later, that even the always battling-against-the-odds, Gavin can "run out of gas". During the tests for Admission into West Point, he couldn't remember any Shakespeare plays and turned in a blank essay. An unsung hero gave him a break, Lieutenant Black conducting the test ordered him to go back and write something which Gavin did and it was just enough to get him appointed to the U.S. Military Academy. Who is to say that if Gavin did not get into West Point that he wouldn't have reached the end of his rope and gone back to his coal mining home town or some other walk of life and how many men would have died because of it? Gavin reminds me very much of Jimmy Stewart's George Bailey in the great post-WW2 1946 movie, "Its a Wonderful Life", except for his greatest common denominator effect to come to pass, he has to go into the service like Bailey's brother does in the story. Also notice I said opportunity---who is to say, the lonely and unloved orphan wouldn't have fell in love with a girl, married and got her pregnant, locking him into fatherhood and immediate financial demands? My mom was an orphan and all her life it affected her ability to love and be loved. To be abandoned by your parents or by world circumstance is and incredibly demoralizing start in the world that requires immense personal courage to overcome.

The lesson to learn here for America today is that EVERY high school graduate needs to leave home and neighborhood and do two years of national service to open their minds and build character to all the positive possibilities of life and not just go into being a worker/consumer. The racketeer powers-that-be certainly do not want this, but this is what America needs if it is to survive beyond the 21st Century.

So Gavin bends-the-rules in order to win and joins the Army as an enlistedman, learning the fundamentals of foot infantry combat techniques in the 1920s. Sometimes the rules have to be bent and the prevailing groupthink refused and Gavin offers an excellent poem on how mankind owes a lot to men who disobey for the common good. Gavin sends home the majority of his meager Army paycheck to his step-parents back home. He spends hours of his time in the library reading to learn more about life and the world and gets accepted into West Point as a self-taught man without benefit of high school.

Saving the Army

At West Point, lacking High School Gavin is in severe catch-up mode, self-teaching himself math late at night but is strong in History so he focuses on his weak areas. He catches up then gets ahead, then climbs to the top few of his class. He then is posted to flight school where he slams into a can't do situation where those running the show want nearly everyone to fail. Gavin, has enough inner confidence now to realize it was not his fault and shrugs off a formal school failure that would end many's careers today. Moreover, he did not retaliate against aviation because of a personal set-back and became the most important post-WW2 Army aviation proponent without letting his lack of being a pilot make him feel unworthy or unqualified for some strange reason. Later, Gavin would become a qualified pilot and rightly call on as many officers as possible to be able to fly to spread ownership of Army Aviation throughout the organization so its fully valued by all parts not become an elitist club, which is yet another wisdom the Army has ignored to our ruin since 1983 when Army Aviation as a separate branch unto itself was created.

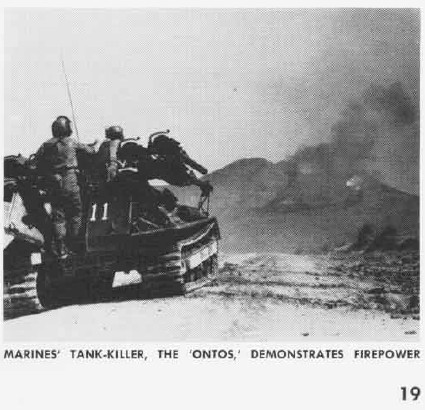

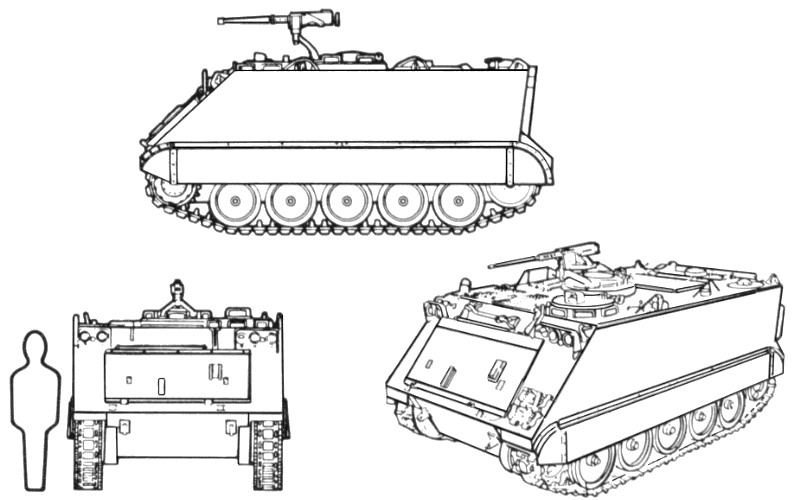

Gavin attends other service schools to get a broad mind on war, which is yet another good idea even the cash-strapped Army of the '30s could do and we need to do today. During tactics discussions, the idea of motorizing infantry in wheeled trucks was examined and found wanting. Thousands of men packed in trucks would extend for literally hundreds of miles in bumper-to-bumper traffic and be an extremely vulnerable target. The conclusion was the infantry would be better off walking then in vulnerable, road-bound wheeled trucks yet here we are today with the Stryker/Humvee truck non-sense with thousands of Americans dead/wounded in Iraq/Afghanistan being blown up along roads/trails that we knew to avoid way back in the 1930s. Gavin in his later 1954 article in Harper's magazine "Cavalry and I don't Mean Horses" would condemn the road-bound nature of the garrison complacent Army in the Korean war debacle and call on air-transportable, light tracked armored fighting vehicles like the Ontos assault gun and M113 armored personnel carrier to be created.

Gavin is appointed to teach tactics at West Point and he sees the build-up of Nazi Germany through intelligence reports into a cross-country mobile, tracked mechanized army and air force working together far superior to the warmed-over WW1 style foot-slogging doughboys backed by artillery mentality of the U.S. Army. He realizes that just catching up to the Germans by copying their war machines would leave us always a step behind and when we actually enter the war we could indeed lose it. Gavin was yet again now in a race to keep up and get ahead and change the situation to enable victory as he had done before when he left his coal mine town, self-taught himself to get into West Point and struggled as a cadet to survive, then thrive to graduate high in his class. Now it was not himself that was dangerously behind the power curve, it was the U.S. Army and drastic measures were in order once again.

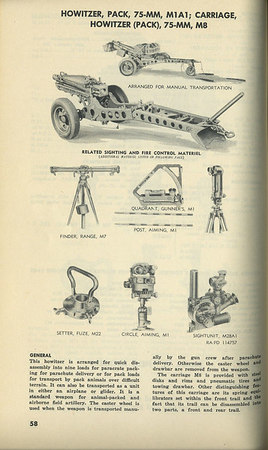

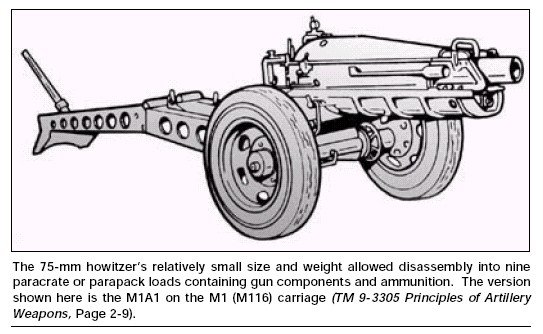

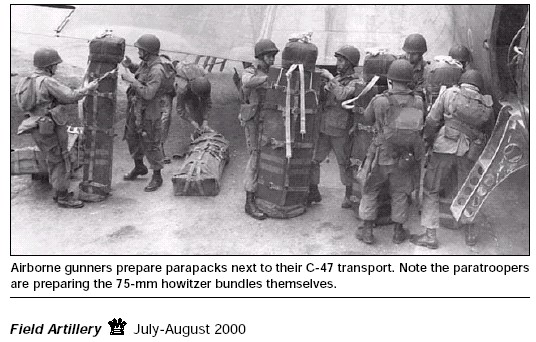

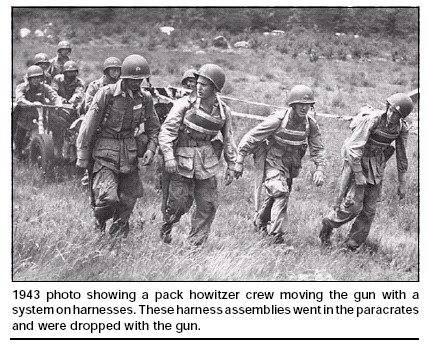

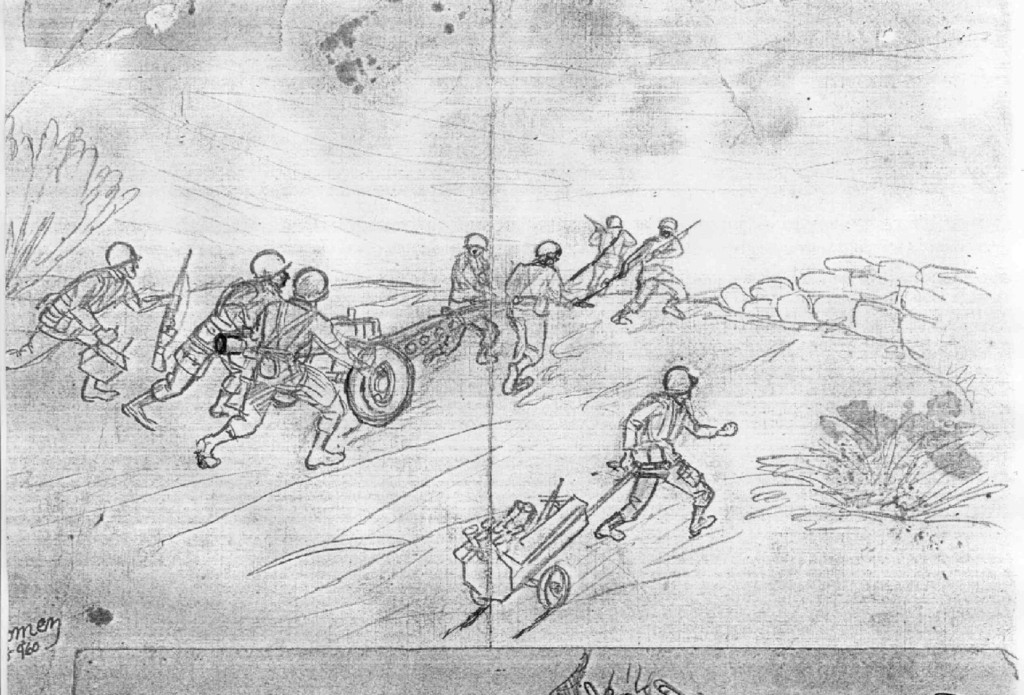

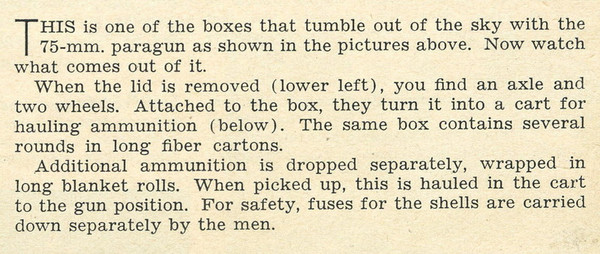

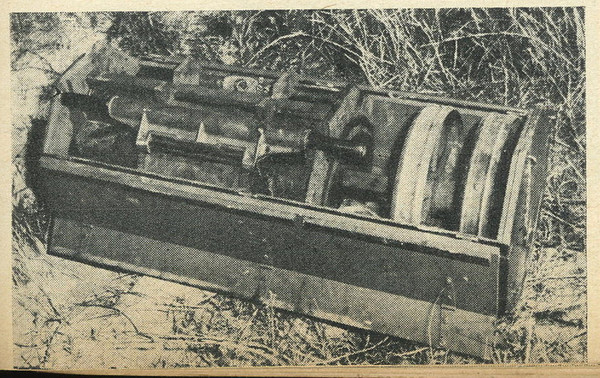

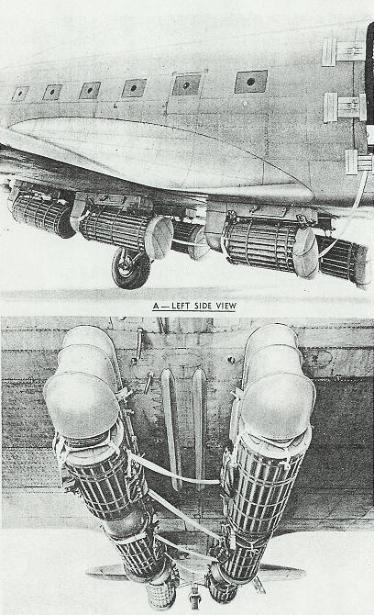

Saving the Paratroopers

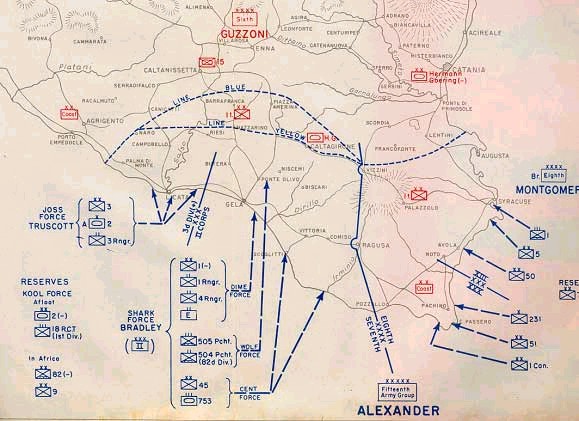

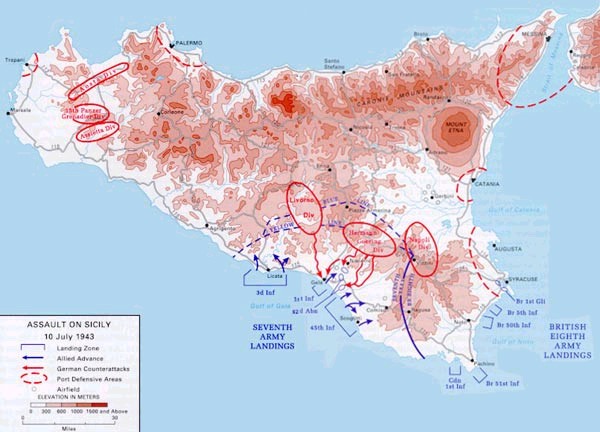

Looking over the German mechanized infiltration style of "lightning war" (blitzkrieg), the decisive factor was that their attacks preceded by parachute and glider troops landing deep behind enemy lines and disrupting the enemy's control of the situation and opening up key terrain points for the tracked tank forces backed by close air support aircraft to pour through. Stonewall Jackson had done the same thing in the U.S. Civil War which resembled WW2 when it was fought with mobility more so than WW1 when it was fought with frontal assaults. Gavin again the gambler, puts in his paperwork to get assigned to the U.S. Airborne being formed at Fort Benning, Georgia but is denied by a typical bureaucratic narrow-minded seeing only the local situation, technicality. Gavin bends the rules and pulls some strings knowing what is at stake even if no one else knows what he must do. He gets into the Airborne and promptly writes the "book" on how to conduct parachute MANEUVER operations, not just seize and hold terrain objectives but to defeat enemy forces far ahead of the main body as a defacto "cavalry". The father of the American Airborne is really not Lee or Ryder, its Gavin. He has his men march mercilessly for 10, 20 miles, stop and think they are to rest, then has them move again to learn how to think well under pressure and confusion. He has the men jump with ALL their equipment to be ready to fight and not to land without their weapons and rely on finding containers which killed many German Fallschirmjaeger on Crete in 1941. He reveals that American 75mm pack howitzers were bundle dropped from under C-47s in 9 separate pieces with their own cargo parachute but connected together by a rope so they all landed together for rapid assembly into firing order. His preparation of his Paratroopers to fight with small unit initiative in non-linear situations was first put to the test on Sicily in 1943.

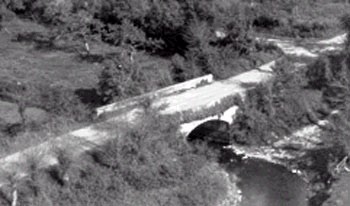

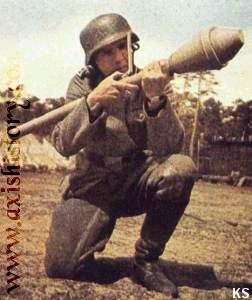

Knowing he would face German Mark VI Tiger heavy tanks, Gavin secures the use of top-secret 2.36" Bazooka rocket launchers to bolster his pack howitzers. After assembling his men after a scattered night jump, he barely holds onto Biazza Ridge as the bazooka rockets often bounce off the German tanks. Those brave men who knock out a German tank with a bazooka get a patch he designed but behind the scenes Gavin is irate that so many of his men had to die due to inadequate weapons because America was asleep before the war. The Germans, capture some bazookas and improve it by increasing its size and begin using their versions on our weakly armored M4 Sherman tanks. Gavin points out that we keep the pathetic bazooka as-is even into the Korean war where in 1950, it bounced off the 100 Russian T-34/85 medium tanks leading the North Korean invasion. The Germans field a disposable anti-tank rocket launcher, the Panzerfaust and Gavin's men get their revenge by capturing truckloads of them and printing instructions in English so they used them against the Germans to knock their tanks out--another little-known secret of why the American Airborne was so more effective than other less imaginative units. The lesson that we should aggressively capture and use enemy weapons against them especially in non-linear situations where our ammunition supplies may not get through is still unheeded in the U.S. Army.

Gavin creates Pathfinders to improve parachute drop accuracy by radio beacons, colored infared lights and radar, a practice that today has resulted in pin-point accuracy that critics of 3D maneuver warfare refuse to admit. The dispersal of men on the desired location is actually a good thing making them harder to engage. Later battles covered in detail in his previous book, Airborne Warfare reveal his frustration with their foot immobility and inability to defeat enemy tanks. Gavin has gliders land 57mm anti-tank guns towed by jeeps (light, unarmored wheeled trucks) but these take time to get ready to fire unlike a light tank with a turret or an assault gun in the hull. Gavin offers the opinion that the "Bridge Too Far" offensive failed because two allied officers lost battle maps to the Germans who then swarmed against the British Airborne's drop zones west of Arnhem over the roads leading to them. He also says that if we had spent less money on B-17 heavy bombers trying to incinerate German citizens and factories and had more C-47 transports we could have landed all of the British Airborne on the first day and got to Arnhem in full force instead of just LTC Frost's battalion as the later units had to wait to jump in on the succeeding days and were then blocked by the Germans.

As the Russians close in from the east, Gavin is ordered to cross a river to take ground before the Russians get there, but he is not ready and needs more time to get his assault boats. General Dempsey says there is no time and he would provide LVT-4 "Buffalo" amphibious armored tractors to lead his men across, which gives Gavin his first taste of the flexibility of having your own tracked armored mobility can provide. What is still a huge mystery is why these amtracks, landing craft and glider-delivered light tanks and Bren gun tankettes with 75mm pack howitzers were not used at Arnhem to break through even in spite of the Germans knowing our plans?

Saving America

As WW2 ends, Gavin runs into the victorious Russians who are already imbued with the communist "party line" that they had single-handedly won the war all by themselves. Try finding pictures before 1989 of American supplied equipment in Soviet "Great Patriotic War" markings. Gavin points out for the communist system to work and have its people deny themselves creature comforts to feed war production they have to be consistently lied to by government controlled press. Soon we are no longer allies but mortal enemies. The atomic bombs are dropped on Japan and we occupy the home islands lest the Russians barge in. Americans eager to embrace peacetime complacency are fed the lie from their own air force that air bombing ended the war with Japan when clearly it was maneuver that surrounded Japan that coupled with Russia declaring war on them and expelling their army from Manchuria that made them surrender.

Gavin points out how the points system (pardon the pun) began to rip the competent get-the-job-done men out of the Army, leaving combat-less men with M24 Chaffee light tanks in storage at the outbreak of the Korean war where Task Force Smith flown in by measly C-54s was over-run by T-34/85 medium tanks when their 2.36" bazookas failed. Gavin criticizes the lack of USAF airlift as a key factor but we know now today that there were C-124 Globemaster IIs and C-119 Flying BoxCars available to fly in M24 Chaffee lighttanks as well as a Navy Landing Ship Tank that delivered dozens of wheeled trucks and towed artillery pieces to TF Smith. The fault was also the Army's for wanting to fight WW1 style with foot/truck infantry-artillery when cross-country mobile light tanks were available and could be delivered.

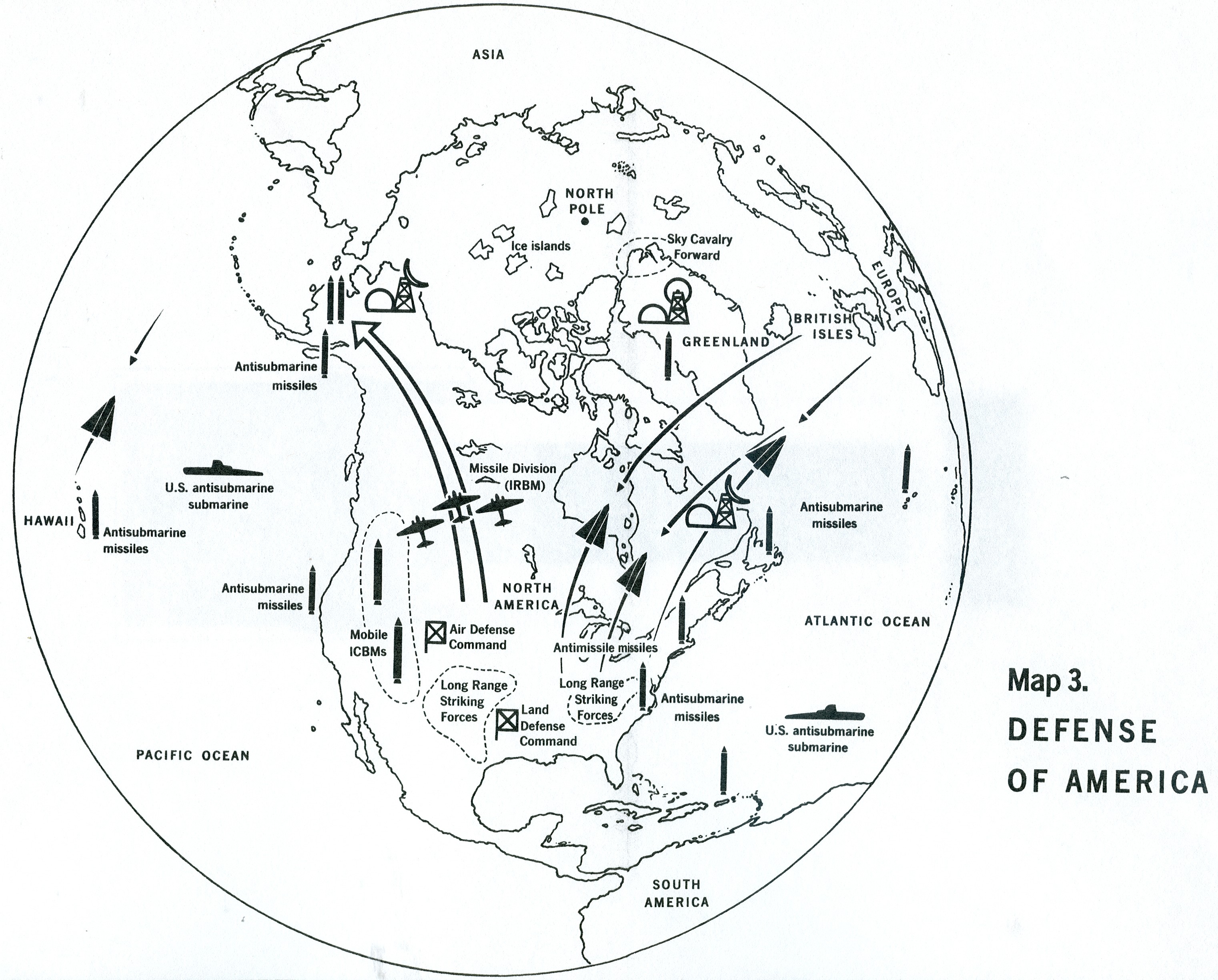

Another revelation in the book was that during the Korean war, Gavin and his VISTA group participated in General MacArthur's Inchon landings and investigated why the Army was notgetting close air support from the USAF's jets while the USMC and USN had some prop plane F-4U Corsairs and A-1 SkyRaiders to save the day. Gavin's VISTA group report called on the USAF to get several hundred C-124s long-range and C-123 short-range transports and the Army to get 9-ton Ontos light tracked assault gun/reconnaissance vehicles that could easily be carried en masse inside them to form a "Sky Cavalry", but the report's measures were not adopted.

Part 2 Concept Book: The Vision

Limited wars need specialized forces

Gavin understands that limited wars need QUALITATIVELY superior forces not just large war forces in smaller amounts. This is a reality that today is not understood nor accepted by our "full spectrum" racketeers who insist that any Soldier or marine can do small, sub-national conflicts well. Gavin laments that when we are not fighting with nuclear weapons or to take a nation-state military down in formal battle we fight unconventional enemies poorly. Gavin is implying that the Army's lighter forces should tackle these limited wars but as the years have played out these tend to be narcissistic egomaniacs who over simplify war to what they can carry in their hands and lack the willingness to use technology and machines (tanks and airplanes etc.) to get the qualitative edge we need.

America must pioneer the high ground of Space and not become complacent

Clearly ahead of his time, Gavin sees space as the overarching physical medium for earth war and wants space militarized by the United Nations so it doesn't become a free-for-all for control.

Gavin was ready to put satellites into orbit first but the selfish Navy Chairman of the Joint Chiefs, Admiral Radford conspired with the Secretary of Defense Wilson to sabotage America's space program out of inter-service back-stabbing.

I disagree with Gavin that interservice rivalry is not a problem when clearly he shows it is.

Totalitarian Sovs are more focused

Its refreshing to read Gavin because he's not such an American cheerleader that he cannot see some virtue in what the enemy does. Gavin notes that in totalitarian regimes the powers of the people can be focused by force to get benefits stronger than free countries floundering without consensus, but he warns that this forced unity is not even close to the powers of unity that free people can create if they can be convinced to work together.

We can come up with better ideas through freedom if we challenge ourselves

America is at its best when physically challenged--Gavin wants us to conquer and explore space and not become selfish consumers. He's right about human nature and has no illusions of America being any different than other peoples if we do not challenge ourselves.

4th Dimension of Strategy Means Winning Without Fighting

Gavin explains how actual war is about getting your will accomplished and this is best done without fighting through the mind. This 4th dimensional warfighting is way above the understanding of today's hate-filled morons who just want to kill ragheads as if murdering enough of them will somehow destroy their IDEAS which are actually bullet and bomb-proof. Gavin wants the greater ideas of freedom to win over by merit not by force alone.

Sovs asymmetric ploys

Its fascinating that Gavin suggests that in this 4th dimensional warfare that the Soviets might have actually egged us on to waste billions on bombers which they knew they could shoot down. If applied today its possible that the enemies of America have egged on our Army and marines to buy sexy wheeled trucks which they can easily blow up by laying a bomb in the road. Americans who think smugly that we are so superior to all the people's of the earth cannot even fathom that our enemies may actually be several moves ahead of us in their actions.

Pre-emptive war immoral: Gavin Nails the Neocons Before they were even CONceived

On pages 250-251, Gavin explains liberal and conservative "Cold War" attitudes and thinking which amazingly predicts the sick attitudes of today's neo-conservatives (neocons) which are really Leo Strauss marxists in democratic sheep's clothing. Since they don't give a damn about people in general; their attitude is kill them before they kill us (pre-emptive war); and have no interest whatsoever in security assistance or any assistance to prevent nation-states from falling into chaos by tangibly solving social ills. Straussians believe that the common people need to be fed a national myth to keep them docile as documented by BBC film maker Adam Curtiss in his series "The Power of Nightmares".

Part 1: "Baby, Its Cold Outside"

http://video.google.com/videoplay?docid=881321004838285177

http://video.google.com/videoplay?docid=881321004838285177

Part 2: The Phantom Victory

http://video.google.com/videoplay?docid=4602171665328041876

http://video.google.com/videoplay?docid=4602171665328041876

Part 3: The Shadows in the Cave

http://video.google.com/videoplay?docid=2081592330319789254

http://video.google.com/videoplay?docid=2081592330319789254

In a previous series, "The Trap" he showed how the neocons to contain communism set up sham democracies to actually keep dictatorships in power while keeping the populace docile with consumerism. Curtis explains how consumerism is manipulated by corporations in his epic series "The Century of the Self" in 2002 broadcast by the BBC as a four-part series. The series tracks how American elites have aggressively used the modern behavioral sciences to persuade, coerce and manipulate the American public into accepting the corporate-government world's version of events as their own.

Part 1: Racketering corporations see people as just emotional, irrational idiots not thinking citizens as per Freud, they go on a binge of consumption and great depression follows

http://video.google.com/videoplay?docid=8953172273825999151

http://video.google.com/videoplay?docid=8953172273825999151

Part 2: FDR saves country but consumerism is re-engaged after WW2 to scare people into building MICC-TT, Freud's daughter stresses social conformity to suppress irrational desires, business provides social conformity products.

This video focuses on one of the most skillful and amoral expert of all the experts in mass manipulation, Edward Bernays. Bernays got his first taste of the power of propaganda during World War I. He advised US presidents from Woodrow Wilson to Einsehower and served numerous corporations and business associations. One of his biggest fans was Hitler's propaganda chief, Joseph Goebbels, a fact about which Bernays bragged proudly.

In this clip, we see a pattern that Bernays used over and over again: turn a harmless entity into a fearsome enemy through lies and manufactured news items. Then use the "threat" to justify attack. The subject of this video is Bernays campaign against the democratically elected government of Guatemala in 1953, but you'll have no trouble seeing that this very same method is being used today (Iraq).

www.guba.com/watch/2000915704

www.guba.com/watch/2000915704

Part 3: Sick of conformity and manipulation by corporations, public wants their desires let loose during wild 60s, society's inhibitions are cause of misbehavior, self fulfillment becomes the goal, instead of society classes, corporations pander to the psychological categories of people

www.guba.com/watch/2000915747

www.guba.com/watch/2000915747

Part 4: Give the People What They Want---Public deceived into thinking products will satisfy them, Corporations and Governments get Control; their elected officials are "products", too consumer-based politics pandering to the mob's primal desires, internally-driven bringing about greater and greater physical reality disconnect--possible ecological collapse as we over indulge and consume, destroying spaceship earth; irrational consumers no longer rational citizens abrogating their social fabric to corporations who have no loyalty to them to provide them jobs out-sources product construction to overseas slave labor to increase profits; disaster coming unless we BOYCOTT their products and make them produce ECOFRIENDLY PRODUCTS BUILT BY US and we demand what's BEST not racketeering thru government intervention thru elected officials we elect not bought by the corporations

http://video.google.com/videoplay?docid=1122532358497501036

http://video.google.com/videoplay?docid=1122532358497501036

After this shamocracy failed in post-communist Russia, they installed a phony "democracy" in Iraq hoping that having an influx of outsider corporations coming in to govern would set up a consumerist society. The Iraqis are not satisfied with a Shia FACTIONOCRACY and certainly not with their nation being a vassal state to American corporations to exploit.

THE TRAP

Part 3: Kissinger backing of brutal dictators in order to contain communism, neocons think we should instead expand negative freedom at gunpoint to roll-back communism, armed struggle + bureaucratic shia islam = freedom? wtfo?, reagen neocons export sham democracy (like in Iraq today), a falsade placebo for the people

www.youtube.com/watch?v=YAqE0J15lGE&NR=1

www.youtube.com/watch?v=YAqE0J15lGE&NR=1

Part 4: Reagen admin lying about Sandanistas having chemo weapons from Sovs etc., liberal democracy hubris, Soviet collapse results in economic collapse

www.youtube.com/watch?v=uzlR5DMLfF8

www.youtube.com/watch?v=uzlR5DMLfF8

Part 5: Yeltsin restores order by force, corporations owned by racketeers have Yeltsin in hock, Putin takes charge, imprisons the robber barons, negative consumerism liberty failed in Russia, neocons back in power lying to America to get them to war

www.youtube.com/watch?v=6ghvI2R1tM8

www.youtube.com/watch?v=6ghvI2R1tM8

Part 6: Bremer fires all capable people like Pol Pot did except without murdering them to get clean slate, country given over to foreign corporations to be governed, massive corruption, typical falsade democracy like during Reagen era, no social contract, rebellion began, we become the French and start torturing/coercion, pre-emptive war manifests as pre-emptive crime arrests, our so-called freedom aka consumersim is not going to hack it in the future

www.youtube.com/watch?v=zZuFpWii2jg

www.youtube.com/watch?v=zZuFpWii2jg

Clearly, General Gavin did NOT advocate exporting shamocracy around the world but REAL, representative democracy that would result in American corporations losing their defacto colonial empires where resources are plundered and people work in sweat shops as slaves. This kind of "freedom" requiring real social change and reforms obviously took too much effort and harmed the corporate masters and mentality of the fuck-you neocons so they decided a sham form of freedom, based on consumerism is that all that is needed to placate the masses.

Gavin's brilliant and moral outlook on societal reform is best seen in his 1968 book, Crisis Now which clearly advocates engaging in direct solving of people's problems not shutting them up with consumer goods.

Surevillance Strike Complex

The main idea of his book is that space offers the ultimate "observation post" to direct fire--possibly nuclear fire on the people below and Gavin as a former artillery enlistedman understands this. Gavin is proposing a surveillance strike complex (SSC) a comprehensive system where we can see all our enemies from space, air, land and sea and be able to express mail a nuke by a guided missile if need be.

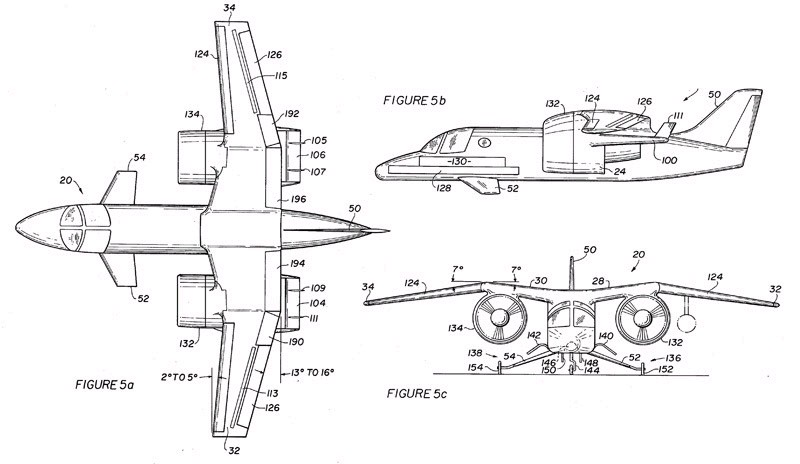

Guidance/nukes, Mobile Ballistic Missiles

Gavin fully understands that a mobile missile like the German V-2s were impossible to counter-target and joined this with guidance to make the world's first precision guided surface-to-surface missiles under his tenure as Army Research & Development Chief. He wants this mobility for SSMs to be even greater through the use of transport aircraft though the USAF is luke-warm to anything but manned bombers and fighters.

SHE--not nukes labels show relationship or you lose the relationship in minds of the linear

Nuclear weapons are really super high explosives (SHE), Gavin understands this but isn't terrified of them and wants to use small nukes to gain certainty of target destruction. Perhaps had Gavin used SHE instead of "nukes" he would not have scared readers and been more "safe" as a Secretary of Defense.

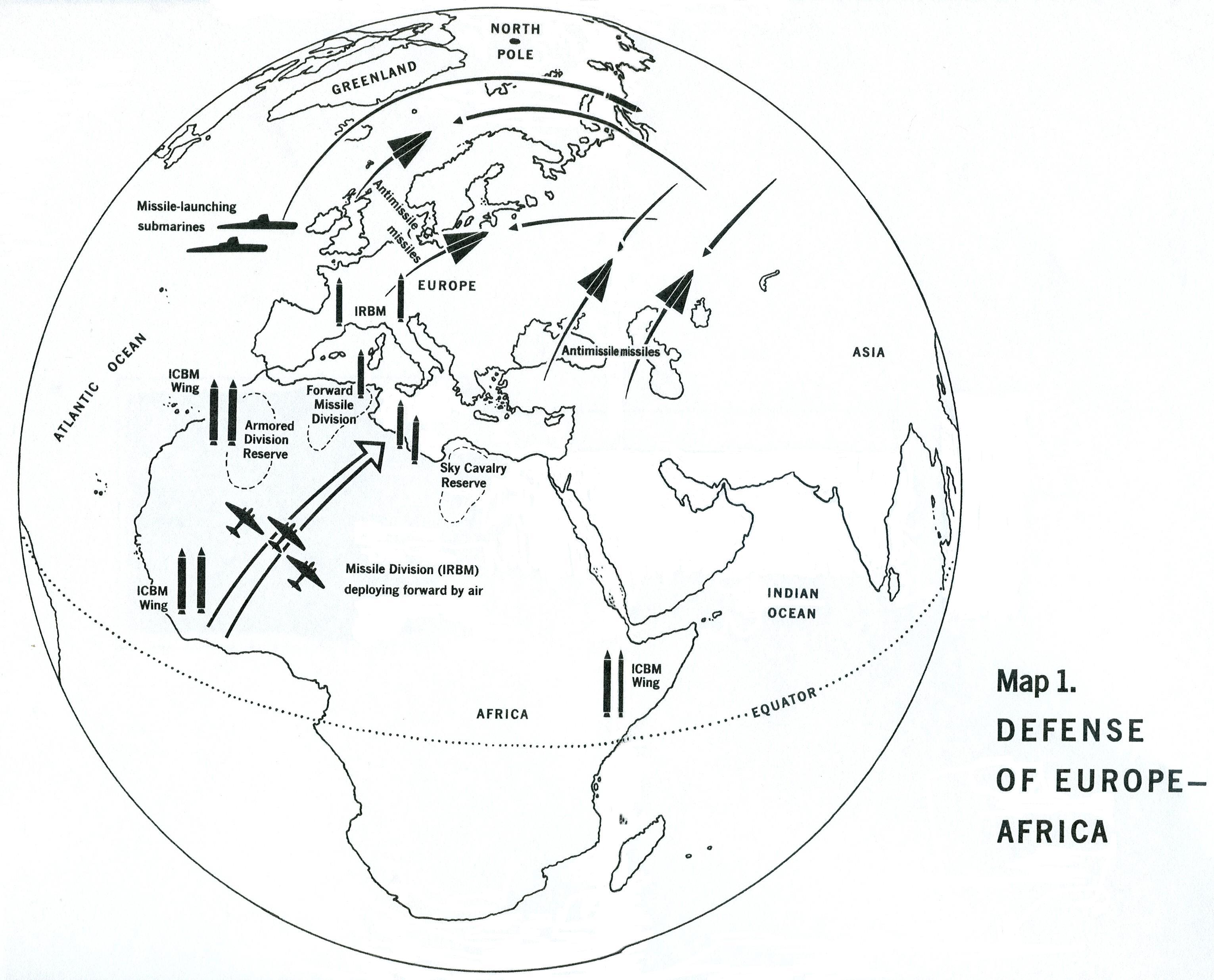

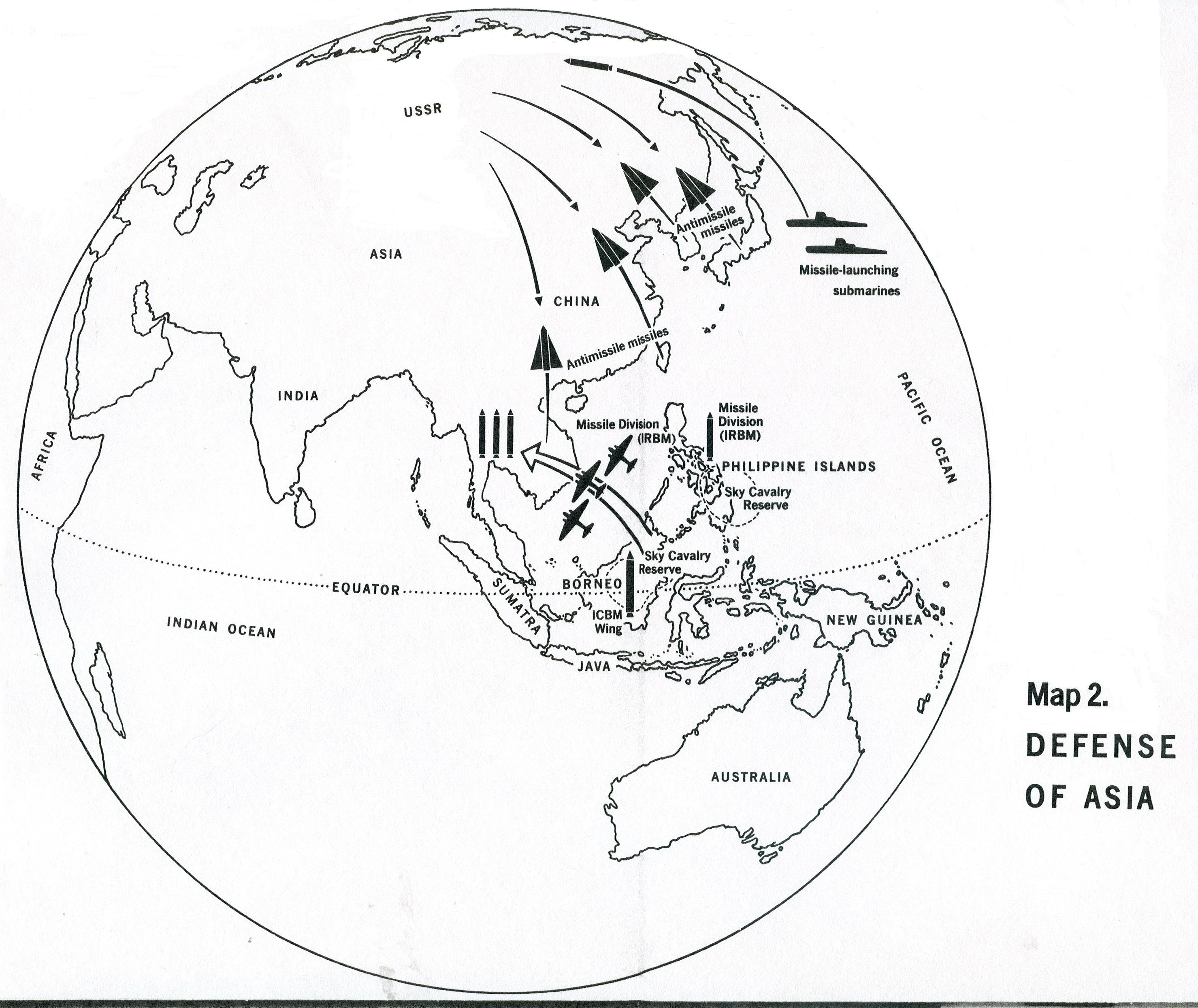

Strategic Use of Terrain

To evade the reach of the SSM, Gavin proposes we look out to Africa and spread our mobile missile forces out to there and at the same time improve relations with those countries. Had we kept with mobile SSMs in this way we could have blocked Soviet communist inroads to these countries, many of whom still suffer economically to the present day. Gavin's book explains why the USAF is averse to mobile missile basing since be on your toes requires an alertness that a static location should have but seems to not need and can be manned like a 9-to-5 job--which is how America's ICBMs are operated today.

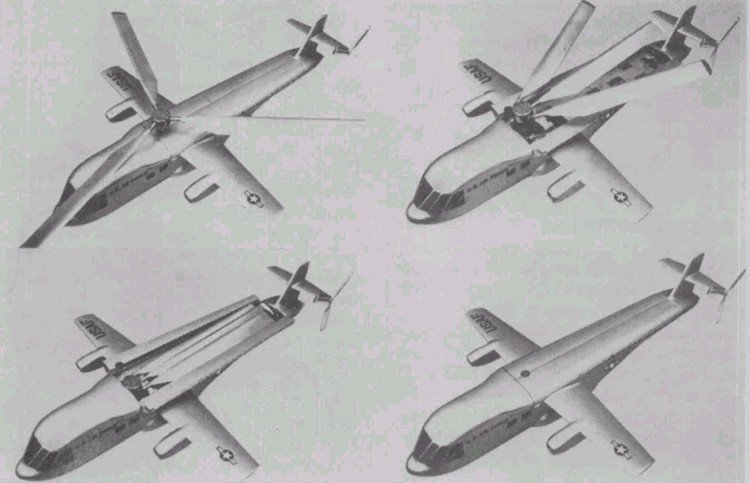

SkyCavalry

Gavin's Sky Cavalry is clearly not just foot-sloggers from helicopters. Gavin wanted VTOL fixed-wing aircraft delivering track-laying vehicles not victims from vulnerable, slow helicopters. Those that want to buy into cliches' and have never read General Gavin's actual words are quick to pin the helicopter air-mobile initiative on him when he was never satisfied with it and complacent with it or anything else. Those that persist with helicopters in the Army disgrace General Gavin's memory and fail to live up to his vision.

Everything Mobile and Armored

An adjunct to the understanding of how lethal the non-linear battlefield is, General Gavin WANTS EVERYONE IN TRACKED ARMOR starting with his baseline M113. Gavin discovers while commanding in Germany that the tracked armored vehicle forces are the only ones with the mobility to disperse and concentrate as needed with protection from nuclear bomb blast, heat and radiation effects. That the Army has still failed to do this, 6 decades later is inexcusable.

DoD is clueless and must be reformed: Clueless civilian mandarins

Gavin explains how the 1947 act creating the Department of Defense (DoD) has been a complete disaster--the people running the Pentagon are clueless. The Joint Chiefs only care abouty their service and the civilians over them have no basis for an educated military opinion of their own. The civilian secretaries are usually taken from business which means they are inclined to racketeer junk for pork. Gavin just doesn't curse the darkness--he offers a tangible solution: provide the civilian secretaries military officers freed from towing their service party line. Of course, his sensible ideas were rejected.

The MICC-TT racket