http://www.lubbockonline.com/news/040697/albuquer.htm

Albuquerque residents die in auto accident

By ELIZABETH LANGTON

Avalanche-Journal

Two adults and a 2-month-old baby died Saturday morning in a fiery car crash north of Post.

Albuquerque, N.M., residents David Dewayne Thompson, 24, Jackie Irene Conn, 24, and Dalton Dewayne Thompson, 2 months, burned to death when their 1991 Oldsmobile exploded into flames, according to Department of Public Safety reports.

''I've been in the funeral business for 30 years and this is one of the worst I've seen,'' Garza County Justice of the Peace Dee Justice cq said.

As justice of the peace, Justice rules in death cases because the county has no medical examiner. Because of the extent of the damage, the bodies could not be identified at the scene. Justice sent them to the Lubbock County Medical Examiner's Office on Saturday for autopsies and identification.

The car was parked on the shoulder of U.S. 84 about 13 miles northwest of Post without any lights as the occupants slept, reports said.

About 3:35 a.m., high winds forced a tractor trailer headed northwest to veer off the road onto the shoulder. The truck driver did not see the car, reports said.

The truck struck the back of the car, and both vehicles slid into the center median, reports said.

The car immediately exploded, trapping the occupants inside, witnesses told authorities. The Oldsmobile was completely burned, Justice said.

The truck's driver, Hoyt Sunday of Paducah, was not injured. A passing driver called 911 on his cellular phone.

U.S. ARMY RECIPE FOR TRAGEDY, AGAIN AND AGAIN

Its late at night, SPC Jim Smith's been driving all night to get home from his unit. Rather than stop and sleep, he wants to get home immediately. He's falling asleep at the wheel. Or he's returning back to his unit and he must be there perfectly on time or he will be punished by UCMJ action that will ruin his military career. Its getting harder and harder for him to stay between the lines on the road. His headlights suddenly flash onto the rear of a car off to his right. "My goodness I'm in the wrong lane!" He swerves to the right to get behind the car in the lane in front of him. This is the last thing he remembers on this earth, the last thing before he hits the parked car, and dies, becoming yet another military Personally Owned Vehicle (POV) accident statistic. This tragedy is replayed too often both in peacetime and war. If you factor in all of the Soldier deaths by roadside bombs, RPGs, and accidents in war with peacetime car deaths and MORE SOLDIERS DIE IN GROUND VEHICLES THAN ANYWHERE ELSE.

Notice: anything that has to do with ground vehicles, the Army and marines screw up...they cannot operate them safely or wisely for tactical effect...they lack the basic empathy of anticipating how civilian divers will react to their non-barrier and non-marker constrained vehicle road blocks/check points....

WHY is this?

Maybe its because 1) American servicemen are products of an American school system that does everything it can to discourage THINKING and making learning a chore and a bore, and doesn't train them well to drive a civilian car 2) once in the service the authoritarian U.S. military culture damn well doesn't want them to THINK 3) the lazy, cheap American garrison mentality has ground vehicles PARKED in motor pools most of the time because its cheaper to do less than more and they do not trust subordinates nor want to educate/empower them. 4) American military would rather have you wake up early and do lawn care and other garrison BS all day so you are sleep deprived and pose less of a risk to question authorities.

Result is when American generals are forced to depart from their BS garrison lifestyle and actually DO THINGS in combat deployments like drive ground vehicles Soldiers are not alert, not mature and not skilled = FATAL ACCIDENTS.

Yahoo! News - Fatal U.S. Military Accidents Up in Iraq

www.yahoo.com/_ylh=X3oDMTB2MXQ5MTU3BF9TAzI3MTYxNDkEdGVzdAMwBHRtcGwDaW5kZXgtaWU-/s/135783/*http://story.news.yahoo.com/news?tmpl=story2&u=/ap/20050218/ap_on_go_ca_st_pe/iraq_us_military

By ROBERT BURNS, AP Military Writer

WASHINGTON - U.S. troops in Iraq (news - web sites) have suffered a rash of fatal vehicle accidents and other non-combat deaths in recent weeks, even as the number killed in insurgent attacks has declined.

Although details of recent accidents have not been made public, some officials believe the jump in their number can be explained in part by turbulence from the troop rotation that is now approaching its peak, with tens of thousands of troops arriving and like numbers going home.

"The sheer volume of soldiers on the ground and high volume of vehicular traffic may reflect a higher rate of individual accidents or non-battle injuries," said Maj. Richard Goldenberg, spokesman for the 42nd Infantry Division of the New York Army National Guard, which is commanding a mixed Guard/regular Army task force responsible for an area of north-central Iraq.

There currently are about 155,000 U.S. troops in Iraq, according to the U.S. military command in Baghdad. That is the highest number of the entire war, including the initial invasion.

The number of troops is expected to drop to about 135,000 over the next month or two as units that complete their one-year tours of duty in Iraq pack up and head for home. Some were held beyond their planned departure dates in order to provide extra security in advance of the Jan. 30 election.

In the first 16 days of February, there were 14 non-combat deaths, compared with 16 combat deaths.

January had the highest number of accidental or other non-hostile deaths for any month of the war, with 51. That included 30 marines and one Navy corpsman killed in a single helicopter crash, on Jan. 26. Even setting that accident aside, the Army alone had 18 non-combat deaths in January - the most for any month of the war except August 2003, when it reported 22.

January also had 47 combat deaths, down from 57 in December and 125 in November.

Although U.S. deaths in insurgent attacks have declined the past two months, the number of attacks has not. The U.S. military command in Baghdad said Thursday that in the two weeks since the Jan. 30 election there have been 1,012 insurgent attacks, compared with 1,876 from Jan. 1-29.

The spike in non-hostile deaths in January and February coincides with the troop rotation, which began in small stages last fall but reached its peak over the past two months. The last time there was a notable increase in non-combat deaths was during the previous troop rotation - in February and March of 2004, according to Pentagon (news - web sites) casualty statistics.

Fatal accidents and other non-hostile deaths are almost inevitable in a war zone, and during 2004 the number reported each month in Iraq stayed within a fairly narrow range - from a low of five in June to a high of 19 in March. The average during the year was 11 per month.

The latest surge in accidental deaths began in mid-January and has continued well into February.

This week alone, vehicle accidents killed at least eight Soldiers and marines. That includes three crashes on Wednesday that killed two marines, two Soldiers and one Iraqi civilian and wounded two Soldiers and two Iraqis. In addition, one Soldier died Wednesday on an unidentified U.S. base in Iraq from what the Army described only as a "non-combat injury."

The names of those latest U.S. casualties had not been released as of Thursday.

The non-hostile deaths also include a Feb. 13 incident in which three Soldiers with the 3rd Infantry Division died in Balad, north of Baghdad, when their Humvee military vehicle overturned while on a combat patrol and plunged into a canal. Air Force Staff Sgt. Ray Rangel died trying to rescue the Soldiers in the canal. The 3rd Infantry Division arrived in Iraq in January.

For the entire war period, the Pentagon says 1,459 U.S. troops have died; 346 were non-hostile deaths.

MILITARY & CIVILIAN POV DEATHS

Let me be brutally honest---if I were a mom/dad who lost their son/daughter in a CAR ACCIDENT for the rest of my life I'd be raising bloody hell til cars and roads and drivers are made a hell of a lot safer.

Why are we not yet at the damn "tipping point" when 40,000 Americans dies each year in car accidents?

If I were President of U.S. I'd get a bill to me withing 24 hours to mandate no one drives a 2,000+ pound moving object called a car until they are LEGALLY RESPONSIBLE for everyone they might kill with it.

Teddy Roosevelt would have done this if he were alive today.

How many more have to die?

AOL News - Is 16 Too Young to Drive a Car?

http://aolsvc.news.aol.com/news/article.adp?id=20050302072509990030& ncid=NWS00010000000001

By Robert Davis, USA TODAY

Raise the driving age. That radical idea is gaining momentum in the fight to save the lives of teenage drivers -- the most dangerous on the USA's roads --and their passengers.

Brain and auto safety experts fear that 16-year-olds, the youngest drivers licensed in most states, are too immature to handle today's cars and roadway risks.

New findings from brain researchers at the National Institutes of Health explain for the first time why efforts to protect the youngest drivers usually fail. The weak link: what's called "the executive branch" of the teen brain --the part that weighs risks, makes judgments and controls impulsive behavior.

Scientists at the NIH campus in Bethesda, Md., have found that this vital area develops through the teenage years and isn't fully mature until age 25. One 16-year-old's brain might be more developed than another 18-year-old's, just as a younger teen might be taller than an older one. But evidence is mounting that a 16-year-old's brain is generally far less developed than those of teens just a little older.

The research seems to help explain why 16-year-old drivers crash at far higher rates than older teens. The studies have convinced a growing number of safety experts that 16-year-olds are too young to drive safely without supervision.

"Privately, a lot of people in safety think it's a good idea to raise the driving age," says Barbara Harsha, executive director of the Governors Highway Safety Association. "It's a topic that is emerging."

Americans increasingly favor raising the driving age, a USA TODAY/CNN/Gallup Poll has found. Nearly two-thirds -- 61 percent -- say they think a 16-year-old is too young to have a driver's license. Only 37 percent of those polled thought it was OK to license 16-year-olds, compared with 50 percent who thought so in 1995.

A slight majority, 53 percent, think teens should be at least 18 to get a license.

The poll of 1,002 adults, conducted Dec. 17-19, 2004, has an error margin of +/-3 percentage points.

Many states have begun to raise the age by imposing restrictions on 16-year-old drivers. Examples: limiting the number of passengers they can carry or barring late-night driving. But the idea of flatly forbidding 16-year-olds to drive without parental supervision -- as New Jersey does -- has run into resistance from many lawmakers and parents around the country.

Irving Slosberg, a Florida state representative who lost his 14-year-old daughter in a 1995 crash, says that when he proposed a law to raise the driving age, other lawmakers "laughed at me."

Bill Van Tassel, AAA's national manager of driving training programs, hears both sides of the argument. "We have parents who are pretty much tired of chauffeuring their kids around, and they want their children to be able to drive," he says. "Driving is a very emotional issue."

But safety experts fear inaction could lead to more young lives lost. Some sound a note of urgency about changing course. The reason: A record number of American teenagers will soon be behind the wheel as the peak of the "baby boomlet" hits driving age.

Already, on average, two people die every day across the USA in vehicles driven by 16-year-old drivers. One in five 16-year-olds will have a reportable car crash within the first year.

In 2003, there were 937 drivers age 16 who were involved in fatal crashes. In those wrecks, 411 of the 16-year-old drivers died and 352 of their passengers were killed. Sixteen-year-old drivers are involved in fatal crashes at a rate nearly five times the rate of drivers 20 or older.

Gayle Bell, whose 16-year-old daughter, Jessie, rolled her small car into a Missouri ditch and died in July 2003, says she used to happily be Jessie's "ride." She would give anything for the chance to drive Jessie again.

"We were always together, but not as much after she got her license," Bell says. "If I could bring her back, I'd lasso the moon."

Most states have focused their fixes on giving teens more driving experience before granting them unrestricted licenses. But the new brain research suggests that a separate factor is just as crucial: maturity. A new 17- or 18-year-old driver is considered safer than a new 16-year-old driver.

Even some teens are acknowledging that 16-year-olds are generally not ready to face the life-threatening risks that drivers can encounter behind the wheel.

"Raising the driving age from 16 to 17 would benefit society as a whole," says Liza Darwin, 17, of Nashville. Though many parents would be inconvenienced and teens would be frustrated, she says, "It makes sense to raise the driving age to save more lives."

By the Numbers

937 Fatal crashes involving 16-year-old drivers in 2003

411 Drivers who died in those crashes

352 Passengers who died in those crashes

Nearly 5X Times more likely a 16-year-old driver will have an accident, compared to a 20-year-old driver

10 percent Frequency that a 16-year-old driver's crash was alcohol-related (compared with 43 percent in drivers 20- to 49-years-old)

77 percent Frequency that a 16-year-old driver's crash involved "driver error"

Source: USA Today, Insurance Institute for Highway Safety

Focus on Lawmakers

But those in a position to raise the driving age -- legislators in states throughout the USA -- have mostly refused to do so.

Adrienne Mandel, a Maryland state legislator, has tried since 1997 to pass tougher teen driving laws. Even lawmakers who recognize that a higher driving age could save lives, Mandel notes, resist the notion of having to drive their 16-year-olds to after-school activities that the teens could drive to themselves."Other delegates said, 'What are you doing? You're going to make me drive my kid to the movies on Friday night for another six months?' " Mandel says. "Parents are talking about inconvenience, and I'm talking about saving lives."

Yet the USA TODAY poll found that among the general public, majorities in both suburbs (65 percent) and urban areas (60 percent) favor licensing ages above 16.

While a smaller percentage in rural areas (54 percent) favor raising the driving age, experts say it's striking that majority support exists even there, considering that teens on farms often start driving very young to help with workloads.

For those who oppose raising the minimum age, their argument is often this: Responsible teen drivers shouldn't be punished for the mistakes of the small fraction who cause deadly crashes.

The debate stirs images of reckless teens drag-racing or driving drunk. But such flagrant misdeeds account for only a small portion of the fatal actions of 16-year-old drivers. Only about 10 percent of the 16-year-old drivers killed in 2003 had blood-alcohol concentrations of 0.10 or higher, compared with 43 percent of 20- to 49-year-old drivers killed, according to the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety.

Instead, most fatal crashes with 16-year-old drivers (77 percent) involved driver errors, especially the kind most common among novices. Examples: speeding, overcorrecting after veering off the road, and losing control when facing a roadway obstacle that a more mature driver would be more likely to handle safely. That's the highest percentage of error for any age group.

For years, researchers suspected that inexperience -- the bane of any new driver -- was mostly to blame for deadly crashes involving teens. When trouble arose, the theory went, the young driver simply made the wrong move. But in recent years, safety researchers have noticed a pattern emerge -- one that seems to stem more from immaturity than from inexperience.

"Skills are a minor factor in most cases," says Allan Williams, former chief scientist at the insurance institute. "It's really attitudes and emotions."

A Peek Inside the Brain

The NIH brain research suggests that the problem is human biology. A crucial part of the teen's brain -- the area that peers ahead and considers consequences -- remains undeveloped. That means careless attitudes and rash emotions often drive teen decisions, says Jay Giedd, chief of brain imaging in the child psychiatric unit at the National Institute of Mental Health, who's leading the study.

"It all comes down to impulse control," Giedd says. "The brain is changing a lot longer than we used to think. And that part of the brain involved in decision-making and controlling impulses is among the latest to come on board."

The teen brain is a paradox. Some areas -- those that control senses, reactions and physical abilities -- are fully developed in teenagers. "Physically, they should be ruling the world," Giedd says. "But (adolescence) is not that great of a time emotionally."

Giedd and an international research team have analyzed 4,000 brain scans from 2,000 volunteers to document how brains evolve as children mature. In his office at the NIH, Giedd points to an image of a brain on his computer screen that illustrates brain development from childhood to adulthood. As he sets the time lapse in motion, the brain turns blue rapidly in some areas and more slowly in others. One area that's slow to turn blue -- which represents development over time -- is the right side just over the temple. It's the spot on the head where a parent might tap a frustrated finger while asking his teen, "What were you thinking?"

This underdeveloped area is called the dorsal lateral prefrontal cortex. The underdeveloped blue on Giedd's screen is where thoughts of long-term consequences spring to consciousness. And in teen after teen, the research team found, it's not fully mature.

"This is the top rung," Giedd says. "This is the part of the brain that, in a sense, associates everything. All of our hopes and dreams for the future. All of our memories of the past. Our values. Everything going on in our environment. Everything to make a decision."

When a smart, talented and very mature teen does something a parent might call "stupid," Giedd says, it's this underdeveloped part of the brain that has most likely failed.

"That's the part of the brain that helps look farther ahead," he says. "In a sense, increasing the time between impulse and decisions. It seems not to get as good as it's going to get until age 25."

This slow process plays a kind of dirty trick on teens, whose hormones are churning. As their bodies turn more adultlike, the hormones encourage more risk-taking and thrill-seeking. That might be nature's way of helping them leave the nest. But as the hormones fire up the part of the brain that responds to pleasure, known as the limbic system, emotions run high. Those emotions make it hard to quickly form wise judgments -- the kind drivers must make every day.

That's also why teens often seem more impetuous than adults. In making decisions, they rely more on the parts of their brain that control emotion. They're "hotter" when angry and "colder" when sad, Giedd says.

When a teen is traveling 15 to 20 miles per hour over the speed limit, the part of his or her brain that processes a thrill is working brilliantly. But the part that warns of negative consequences? It's all but useless.

"It may not seem that fast to them," Giedd says, because they're not weighing the same factors an adult might. They're not asking themselves, he says, " 'Should I go fast or not?' And dying is not really part of the equation."

Precisely how brain development plays out on the roads has yet to be studied. Giedd says brain scans of teens in driving simulations might tell researchers exactly what's going on in their heads. That could lead to better training and a clearer understanding of which teens are ready to make critical driving decisions.

In theory, a teen's brain could eventually be scanned to determine whether he or she was neurologically fit to drive. But Giedd says that ethical crossroad is too radical to seriously consider today. "We are just at the threshold of this," he says.

Finding Explanations

The new insights into the teen brain might help explain why efforts to protect young drivers, ranging from driver education to laws that restrict teen driving, have had only modest success. With the judgment center of the teen brain not fully developed, parents and states must struggle to instill decision-making skills in still-immature drivers.

In nearly every state, 16-year-old drivers face limits known as "graduated licensing" rules. These restrictions vary. But typically, they bar 16- year-olds from carrying other teen passengers, driving at night or driving alone until they have driven a certain number of hours under parental supervision.

These states have, in effect, already raised their driving age. Safety experts say lives have been saved as a result. But it's mostly left to parents to enforce the restrictions, and the evidence suggests enforcement has been weak.

Teens probably appear to their parents at the dinner table to be more in control than they are behind the wheel. They might recite perfectly the risks of speeding, drinking and driving or distractions, such as carrying passengers or talking on a cell phone, Giedd says. But their brains are built to learn more from example.

For teenagers, years of watching parents drive after downing a few glasses of wine or while chatting on a cell phone might make a deeper imprint than a lecture from a driver education teacher.

The brain research raises this question: How well can teen brains respond to the stresses of driving?

More research on teen driving decisions is needed, safety advocates say, before definitive conclusions can be drawn.And more public support is probably needed before politicians would seriously consider raising the driving age.

In the 1980s, Congress pressured states to raise their legal age to buy alcohol to 21. The goal was to stop teens from crossing borders to buy alcohol, after reports of drunken teens dying in auto crashes. Fueled by groups such as Mothers Against Drunk Driving, public support for stricter laws grew until Congress forced a rise in the drinking age.

Those laws have saved an estimated 20,000 lives in the past 20 years. Yet safety advocates say politicians remain generally unwilling to raise the driving age.

"If this were forced on the states, it would not be accepted very well," Harsha says. "What it usually takes for politicians to change their minds is a series of crashes involving young people. When enough of those kind of things happen, then politicians are more likely to be open to other suggestions."

http://aolsvc.news.aol.com/news/article.adp?id=20050301065609990011

Deadly Teen Auto Crashes Show a Pattern

By Jayne O'Donnell, USA TODAY

HOLLYWOOD, Fla. -- It was a double date like countless others: Two teenage girls and their teenage boyfriends, with plans to see a movie on a summer night.

But this one ended in grief. Sixteen-year-old Gerald Miller swerved his sport-utility vehicle to miss a car stalled on Interstate 95. The SUV, traveling about 78 mph, rolled five times. The boys were injured. The girls -- Casey Hersch, 16, and Lauren Gorham, 15 -- were thrown from the SUV and died.

To many who knew the victims, the crash seemed like a cruel act of fate, a freak tragedy beyond anyone's control. But it fit a common formula for teen deaths on the USA's roadways: Put a 16-year-old boy at the wheel of an SUV. Add two or three teens, including at least one other boy. Send them out at night. Finally, let them travel fast -- and unbelted. Those common factors emerged when USA TODAY examined all the deadly crashes involving 16-to-19-year-old drivers in 2003. About 3,500 teenagers died in teen-driven vehicles in the USA that year - a death toll that tops that of any disease or injury for teens. The South proved to be the deadliest region.

More than two-thirds of fatal single-vehicle teen crashes involved nighttime driving or at least one passenger age 16 to 19. Nearly three-fourths of the drivers in those crashes were male. And 16-year-old drivers were the riskiest of all. Their rate of involvement in fatal crashes was nearly five times that of drivers ages 20 and older, according to the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety.

Teen Brains Not Developed

New medical research helps explain why. The part of the brain that weighs risks and controls impulsive behavior isn't fully developed until about age 25, according to the National Institutes of Health. Some state legislators and safety activists question whether 16-year-olds should be licensed to drive.

Sixteen-year-olds are far worse drivers than 17-, 18- or 19-year-olds, statistics show. Tellingly, New Jersey, which has long barred 16-year- olds from having unrestricted driver's licenses, for years has had one of the lowest teen fatality rates in the USA.

Other jurisdictions, too, have found the only sure way to cut the teen death toll is to limit unsupervised driving by 16-year-olds. Seven states and the District of Columbia don't give unrestricted licenses to anyone under 18. In Britain and Germany, teens can't drive until ages 17 and 18, respectively.

Rules that restrict driving at 16 have clearly had a positive effect, the insurance institute says. As the proportion of 16-year-olds in the USA with driver's licenses has declined from a decade ago, so has the proportion of 16-year-olds involved in fatal crashes. But the rate among those who are licensed has shown no improvement.

On an average day in the USA, 10 teenagers are killed in teen-driven vehicles. Some days are far worse. Crashes that occurred on one of the deadliest days of 2003 - Nov. 1 - killed 26 teens.

The death toll could swell in coming years. A record 17.5 million teens will be eligible to drive once the peak of the "baby boomlet" hits driving age by the end of this decade - 1.3 million more than were eligible in 2000.

Horrific as teenage deaths are, the collective response from their families is often one of grim acceptance. Jeffrey Runge, a former emergency room doctor who's now head of the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, shudders to recall how some parents reacted to hearing their teens had just died in a crash.

"It was amazing how many people would say, 'I guess it was just his time,' " Runge says.

Runge acknowledges that safety advocates have failed to adequately publicize what's known about why teens die in crashes. State laws often don't restrict behavior that's linked to many teen fatalities.

Nearly all states have some form of "graduated licensing" programs that limit driving privileges for new teenage drivers. In some states, the rules restrict whom teens can transport and when they can drive. Teen fatalities have declined in states with the programs, according to a new report by the insurance institute.

But the institute and other safety experts note that despite those programs, thousands of teens are still being killed on the roads. The reason, they say: Graduated licensing rules are poorly enforced and often riddled with loopholes.

When Risks Rise

A review of crash statistics finds clear patterns. The risk to teen lives rises when:

· A 16-year-old is at the wheel.

Along with their higher rate of involvement in fatal crashes, 16-year- olds make driving errors, exceed speed limits, run off roads and roll their vehicles over at higher rates than do older drivers involved in fatal crashes.

"They're the youngest, so they are all inexperienced at that age," says Allan Williams, the institute's former chief scientist. "They're pushing the limits, trying out new things ... and they don't really have the controls over risk-taking in terms of judgment and decision-making."

· They're riding with other teens.

Forty percent of 16-year-old drivers involved in deadly single-vehicle crashes in 2003 had one or more teen passengers. Teens' risk of dying nearly doubles with the addition of one male passenger, the insurance institute says. It more than doubles with two or more young men in the car.

Jackie Swanson, 18, had two passengers -- her 16-year-old cousin, Thomas, and a 17-year-old friend, James Newton -- and was driving about 90 mph when she lost control of a Firebird convertible in a 2003 Louisiana crash. Swanson struck another car, scaled a guardrail and went airborne across several lanes of traffic. The three unbelted teens were ejected and killed.

Thomas Swanson, Thomas' father and Jackie's uncle, says the loss forced him to relapse temporarily into cocaine addiction. "I was trying to bury the deaths with the drugs," Swanson says.

· They're in teen-driven cars after dark.

Teen drivers are three times as likely as drivers 20 and older to be involved in fatal crashes between 9 p.m. and 6 a.m., the institute says, and 16-year-olds die at night at twice the rate as in the daytime. It's harder to see at night, so it's harder to react quickly to obstacles. Inexperienced drivers are more vulnerable to making errors after dark.

Jennifer McElmurray, of Evans, Ga., who turned 16 in February 2003, was driving that June when she lost control of her car and hit a stand of trees. Her car was engulfed in flames. McElmurray survived the crash, but her two male passengers, ages 16 and 17, died. The nighttime curfew for new drivers was midnight; the sheriff was called to the scene at 11:56 p.m.

· The young driver loses control.

Driver error is involved in 77 percent of fatal crashes involving 16- year-old drivers but in less than 60 percent of crashes with drivers 20 and older.

About a third of all 16-year-old drivers and a quarter of 17-to-19- year-old drivers involved in fatal crashes rolled their vehicles. Rollovers often occur when a driver overcorrects and runs off the road. Inexperienced teens are most likely to do so.

On a July night in 2003, Jessie Bell, 16, was following a car driven by her boyfriend on a Missouri highway with a 65-mph speed limit when she lost control. The vehicle rolled into a ditch, and she died.

· They're in an unsuitable vehicle.

Because they're in the age group most likely to be involved in a crash, teens should occupy vehicles least likely to roll and most protective when they crash, highway safety experts say. Yet, teens often wind up in small cars, which are especially vulnerable when hit by larger vehicles, or in SUVs, which are more prone to roll over.

Two years ago, Runge caused a stir when he noted he would never let his inexperienced teens drive a vehicle with a two-star (out of five) rollover rating from the safety administration. Only SUVs and pickups score that low in the ratings.

Terry Khristian Rider, 16, died after he was partly ejected from the GMC SUV he was driving in a 2003 crash in Orangeburg, S.C. His uncle, John Rider, says Terry borrowed the vehicle to drive his girlfriend home before midnight. "Those things are kind of top-heavy, and it doesn't take a whole lot of correcting to roll them," Rider says. "I think it's wrong for people to let kids drive (SUVs)."

· They drive in more dangerous regions.

Eight of the 10 states with the highest teen-driver fatal crash- involvement rates are in the South. Highway safety officials from Southern states, including Alabama, Louisiana and Mississippi, say lax enforcement of speeding or alcohol laws and many rural, tree-lined roads that provide little margin for error make their states deadlier for young drivers.

Kim Proctor, Mississippi's highway safety chief, blames weak seat- belt laws in her state, Florida and Kentucky and difficulty in getting many pickup drivers and minorities to buckle up.

Parents Have no Idea

Kathy Schaefer, the mother of Florida crash victim Casey Hersch, and Melissa Herberz, Lauren Gorham's mother, had no idea of the odds their daughters were facing the July night they were killed.

"I was a very controlling parent," Schaefer says. "But I never thought my child would be killed in a car."

To this day, Schaefer frequently stays in her bedroom all day, mourning the loss of her only child.

The mothers didn't know that the vehicle their daughters were in at the time - a Ford Explorer Sport Trac SUV with a pickup bed - had earned a low two-star government rollover rating. Nor did they recognize the risk the girls faced with a 16-year-old boy driving several passengers. Male teen drivers are about 75 percent more likely than female teen drivers to be involved in fatal crashes, the insurance institute says.

Florida had the fourth-worst teen fatal-crash rate in 2003. It isn't among the 28 states that restrict how many passengers 16-year-old-drivers can have, and it's one of 30 states that forbid police to stop drivers solely for not wearing safety belts; none of the teens was belted.

Florida does have an 11 p.m. driving curfew for 16- and 17-year-old drivers. The crash occurred just after 9 p.m.

Highway safety officials around the USA complain that many state legislators, pressured by parents, have refused to tighten laws to bar teens from driving at night or from having teen passengers, despite clear evidence those factors sharply raise the risk of teen deaths.

Safety officials note that of the 38 states with nighttime driving restrictions, more than half don't start those restrictions until at least midnight - when, they say, most younger teens are not out.

"There's so much research that has shown (graduated licensing) makes a huge difference that we have been trying almost desperately to get (our law) upgraded," says Alabama traffic safety chief Rhonda Pines. Alabama lets 16-year-olds drive after midnight if they're returning from a hunting or fishing trip and have their parents' consent. The state also lets 16-year-olds have up to three teen passengers, in addition to family members.

There are also regional disparities in how alcohol and speeding prohibitions are treated. In Mississippi, where fatalities often occur on tree- lined roads, only one county authorizes sheriffs to use radar guns. Speeding laws are seldom enforced on those roads, Proctor says.

Some states will license even teens who got speeding tickets while driving with a learner's permit.

James Champagne, chairman of the national Governors Highway Safety Association, laments what he calls a casual attitude toward alcohol abuse in his home state of Louisiana. Yet Champagne, a former state police lieutenant colonel, notes it isn't easy to enforce graduated licensing. "Police will look at it as a priority depending on what importance the public puts on it," says Champagne, the Louisiana governor's highway safety director.

Those who advocate graduated licensing say the laws assume parents will enforce them. But interviews with safety officials and crash reports suggest parents often let teens skirt the laws, don't know the rules or aren't aware their kids are driving. The parents of at least two teens killed in 2003 car crashes thought their kids were washing, not driving, the car.

"We don't have police officers on every corner," Champagne says. "Too many parents expect the police to be the parent."

Hard to Move Forward

Gayle Bell was doing everything that seemed appropriate for a parent when Jessie died in her crash. But she no longer thinks 16-year-olds are old enough to drive. Jessie was ejected from her Chevrolet Cavalier coupe in El Dorado Springs, Mo. Bell says the grieving "melts your body down."

Jessie got her license in March 2003 and her car three months later. She was driving the next month, at night, when she crashed.

"Really, the only way to get the experience is to go out and drive," Bell says. "If I had to swerve, I would know how to do it. Jessie really didn't."

Marvin Zuckerman, a psychologist and former professor at the University of Delaware, for years has studied another reason, beyond inexperience and immaturity, why teens tend to be risky drivers. He calls it "sensation seeking."

In driving terms, it's a desire to derive a thrill from the experience. Zuckerman doesn't think full licenses should be awarded until age 21. His research has found that the desire to take risks and act impulsively peaks around age 19 or 20. "It's no coincidence the peak accident rates are in those age ranges," Zuckerman says.

James Avello, 18, Hersch's former boyfriend, who recovered from injuries he suffered in the crash, says the loss of their friends has had little effect on the driving of his classmates at Chaminade-Madonna College Preparatory School. Avello sold his SUV in favor of a less rollover-prone Mazda Millenia sedan. But many teens, he says, drive their own, often-sporty, cars to school on major highways.

Gerald Miller, 18, the driver in the crash, transferred to another high school after enduring death threats from classmates who blamed him for the deaths, says his mother, Geralyn. She says her son needed intensive therapy.

On the 8th of every month, Schaefer visits the spot on I-95 where her daughter was killed on July 8, 2003. It's marked with an Eeyore, Winnie the Pooh's slow but lovable donkey sidekick. Her daughter's volleyball coach gave her that name during a lackluster performance, and it stuck.

After the crash, Casey Hersch's mother and stepfather moved out of the family home to try to escape their anguish. The family still owns the home, now unoccupied. Casey's bedroom, filled with Eeyores, remains untouched. Schaefer still runs the girl's volleyball team concession and goes to school soccer games. Those are about the only commitments in life that she keeps.

"A mother's life is all about being devoted to her child," says Schaefer, who chose laughter as her cell phone ring tone because she so seldom hears it anymore. "One crazy night took everything away."

(Contributing: Barbara Hansen, Anthony DeBarros and Robert Davis )

03-02-05 11:21 EST

WHERE'S THE WAILING WALL FOR THE 40,000+ AMERICANS WHO DIE EACH YEAR IN AUTO CRASHES?

When 58,000 Americans died heroically defending freedom in Vietnam, we built a wall and remembered them. When 40,000 Americans die each year going to the store to feed their children, take them to school, go to church, do we even stop to mourn their loss of human potential? How many could have discovered cures for diseases? We'll never know because our inefficient POV transportation system killed them. Were their deaths any less heroic? Maybe its time we stop this BS.

There were 365,000 crashes into parked motor vehicles in 1995. This was 5.5% of ALL motor vehicle accidents. 43,000 people were injured in these accidents. 458 PEOPLE DIED.

--NHTSB Traffic Safety Facts, 1995, page 54 Table 32 "Crashes by harmful event, manner of collision, and crash severity

Reader's Digest seems to be doing the best job trying to alert apathetic Americans to road safety:

Rear-end collison explodes gas tank of state trooper

Teen drivers: what you can do to keep them alive

Thrilled to death: teen drivers

Worst 5 areas in the U.S. to drive

SAFER EMERGENCY STOPS ALONG ROADS

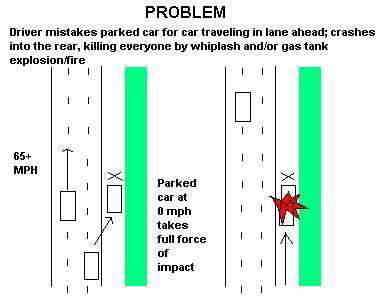

The cause of the highway parked vehicle collisions is people pulling their car over to the shoulder of the road and drivers nearby not being alert thinking that it is a car moving in front of them. The excuse "the parked car should've had his flashers on" is a tired one and the dead people cry out against it, because it doesn't work. Even with the flashers on, it still looks like a car, because it is a car. Its very easy to swerve behind the taillights thinking its the proper lane to be in and within seconds its a fiery head-on collision with the full force taken by the parked car.

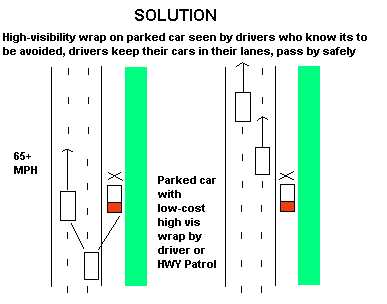

The solution, we need a low cost, plastic wrap in blaze orange and black with reflective strips that highway patrol officers can carry by the box in the trunk of their car. When they see an abandoned car on the side of the road, they can stop and put the wrap on the rear end of the car, so it will look like a large construction barrel, etc. and not be confused with moving cars. One of these rear end safety wraps should be required safety equipment on every American car coming out of the factory and be in the trunk of every American car by the year 2001, by Federal Legislation. Unit commanders can order their men to have them in order to pass vehicle inspections.

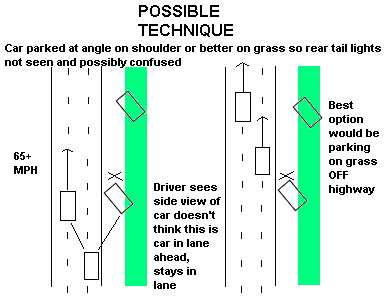

Another solution is to pull off the shoulder and onto the grass and point the car nose to the left so the rear of the car is not seen and confused as a car moving up ahead.

MERGING LANE COLLISIONS

A second major cause of accidents is swerving into a lane where there is another car. Every car has a blind spot where the rear view mirror cannot see a car in another lane. The one dollar solution is a blind spot mirror that can be stuck on the rear view mirror by the driver's window. This should be mandatory on all cars by the 2001, by Federal Legislation. Again, Soldiers must have one in order to pass post vehicle inspections.

CRASH-WORTHY CARS, ANYONE?

ALL cars should have their speed restricted to 70 mph, PERIOD. A lot of so-called ivory-tower "safety experts" make the excuse that safer cars would only encourage drivers to drive more recklessly. Lets end their excuses for laziness by stopping the speedomoter at 70. THEN------cars should be designed to survive a 70 mph impact in ANY direction. If there is a will there is a way. NASCAR cars can survive even worse impacts. So there is no excuse why the 360/70 mph goal couldn't be met with a hidden roll cage and strengthened car body. America's lazy "cannot-do, make-excuse-BS attitude needs to be overcome with good old fashioned, give-a-damn-about-your-neighbor "CAN-DO" that built this country in the first place.

Babies too small for car seats or on airplanes need a safer way to be carried then to be loose on the mothers lap. We need a special baby carrier harness that would carry the baby in a pouch at the mother's front but would have an attachment so the shoulder/car safety belt clips into the harness while on the lower end the mother's harness clips in to the car's female end. This universal safety carrier (USC) would also have a horizontal adapter for airline lap belts. U.S. Army Natick Labs could help design this item.

Why in the world do airliners not have shoulder safety belts like cars? An airplane is moving at hundreds of miles an hours when it crashes, yet passengers have only a lap belt which we instruct them to tuck their heads into a pillow to try to avoid the forward whiplash. Why in the hell are we doing this? Why are their no safety belts of any kinds on school buses? Safety belts will not only save school children lives but will also enable the bus driver to control the children better. Put a car shoulder and lap type safety belt on every single airline and U.S. Military transport aircraft when using passenger-type seats. Believe me, every American is familiar with the car type seat belt and would appreciate the greater safety of this kind of belt when flying on commercial airliners, and all school buses. These kinds of belts should be mandatory on all U.S. airliners by Federal Decree by the year 2001.

Secondly, airliner seats should face REARWARD like they do in military aircraft with passenger seats so of all accidents take place:the back is in a supported upright position instead of the ridiculous head down position prior to a crash.

AVOID DANGEROUS AREAS

State Farm Insurance lists the most dangerous intersections where 1/3 of all accidents take place:

Top 10 Dangerous Intersections

| They also list by state: |

Many crashes could be avoided with low-cost improvements

State Farm Insurance, the nation's largest auto insurer, says about one-third of all crashes happen at intersections. And a significant number of them are deadly. The National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) counted 8,814 fatal crashes at or near intersections in 1999--about 23 percent of all fatal crashes in the nation.

What types of crashes occur?

What types of crashes occur at intersections? "The rear-end collision seems to be the most common, probably because vehicles often are required to stop at intersections.

Side-impact or angle collisions, potentially serious.

Frontal collisions are probably the least common.

Why do these crashes happen?

A traditional way to answer this question is to ask, "What did the driver (or drivers) do to cause this crash?" From that viewpoint, there are many possible answers: Red-light running. The Insurance Institute for Highway Safety (IIHS) says running red lights and other signal violations -- such as disobeying yield and stop signs -- is the most frequent cause of urban crashes. Violating traffic controls accounts for 22 percent of all urban crashes and 27 percent of the injuries that result from them, according to the IIHS. Motorists are more likely to be hurt in crashes caused by red-light running than in any other type of urban crash.

Overall, according to the IIHS, red-light running accounts for more than 200,000 injuries and more than 800 deaths per year.

Failure to yield.

It may take the form of a driver attempting a left turn in the face of oncoming traffic, or perhaps trying to make a right turn on a red light when the way isn't clear.

Following too closely, or tailgating -- a key factor in rear-end collisions.

Speeding, including trying to "beat" a red light by speeding up and hitting another car whose driver anticipated a green light.

Inattentiveness, such as talking on a cellular phone, tuning a radio or eating while driving, or simply being preoccupied and not paying enough attention to traffic.

Occasionally, the car ("My brakes failed") or external factors ("I slid on the wet pavement" or "I was blinded by the sun") may be blamed for the crash.

All of these are legitimate responses to the question of what caused the crash. But in many cases, they may not tell the whole story.

Could the intersection be at 'fault'?

For example, let's take the left-turning driver who is broadsided by an oncoming car. The police report will say this crash was caused by the left-turning driver's "failure to yield"; he'll be judged at fault and may receive a ticket. But why did this crash happen?

Suppose there is no left-turn signal at this intersection and the driver got tired of waiting for traffic to clear and decided to take a chance.

Or maybe there is a left-turn signal, but it doesn't stay green long enough for all the waiting drivers to make their turns. So one driver follows another into the intersection after the light has turned red.

Or perhaps the line of sight--a driver's field of vision -- at the intersection is so fuzzy that the driver of the left-turning car couldn't see the oncoming vehicle in time to avoid the crash.

In other words, something about the intersection itself may have contributed to the crash--and in most cases, something probably can be done about it.

Traffic engineering experts have estimated that between 30 percent and 60 percent of all crashes could be prevented or made less severe through road improvements -- a key component in making intersections more driver-friendly.

Once a community has identified a hazardous intersection, a professional study often is needed to determine exactly what's causing the crashes, what can be done to prevent them, and how much the fixes would cost.

The study begins with visits to the site to find out such things as why "near misses" occur; how much congestion exists and to what extent it delays getting through the intersection; and whether any signal timing or line-of-sight problems exist. Later, police reports for several years will be analyzed to see what times of the day, week and year crashes occur at the intersection; exactly where in the junction they happen; and how such factors as weather, pavement conditions and lighting may be contributing to crashes.

After analyzing this information, traffic engineers can determine what the problems are and propose solutions for each. Some problems--such as faulty signal timing -- are relatively easy and inexpensive to solve. Others--the need to widen the intersection to add left-turn lanes, for example--are more time-consuming and costly to fix. To help local officials decide which options to pursue, engineers can also forecast what kinds of crash and injury reductions can result from improvements and how long it would take for funds spent on them to be offset by lower costs from fewer crashes.

What can be done to reduce crashes?

Solutions, of course, will vary with each intersection. The Insurance Institute for Highway Safety (IIHS) and State Farm recommend these measures that can be taken to reduce intersection crashes: Better traffic-signal timing aimed at reducing unnecessary stops and preventing rear-end collisions. Also, brief red-in-all-directions signals would prevent some cross-traffic crashes.

Adding left-turn-only lanes and allowing left turns only when traffic from the opposite direction is stopped.

Improving the visibility of signals, such as by making them brighter, or larger, or installing an additional signal head.

Giving pedestrians time to start across an intersection before turning vehicles are allowed there, and more time to cross wide, busy roads. Ensuring that pedestrian facilities such as sidewalks, cross walks, pedestrian signals, push-button activation of signals and letdown ramps are available and operating properly.

Removing signal lights at intersections with a low traffic volume and replacing them with four-way stop signs or roundabouts--yield-at-entry traffic circles. This actually improves safety in many situations. A signal-removal program in Philadelphia reduced crashes by an estimated 24 percent.

Where appropriate, converting two-way stop signs to four-way stops. This has been shown to reduce crashes by 40 percent to 60 percent and injury crashes by 50 percent to 80 percent.

Making more widespread use of roundabouts, which slow down drivers and make some types of crashes less likely. A study by the IIHS and researchers at two universities showed that roundabouts reduced overall intersection crashes 39 percent and injury-producing crashes 76 percent.

Use of "traffic calming." This term refers to a variety of measures designed to slow down vehicles, such as speed bumps, rumble strips and the narrowing of streets (through on-street parking, plantings and wider sidewalks) to encourage drivers to go to other streets better able to handle a high traffic volume.

Ensuring that speed limits are appropriate for the street and neighborhood.

Installing skid-resistant pavement cuts down on rear-end crashes, especially in rainy or snowy weather.

Improving lighting at intersections makes it easier for drivers to see all the traffic and reduces nighttime crashes.

If running red lights is a significant factor, Red Light Cameras may be the answer.

Usually, a camera is mounted on a pole and wired to a traffic signal, with sensors buried in the intersection. If a vehicle crosses the sensors while the light is red, that triggers the camera, which produces a photo showing the car, its license plate, and the date and time of the violation. Police mail a ticket with the photo to the vehicle's owner.

Several studies have shown that, these cameras, in use in at least several dozen cities, do reduce red-light violations. The IIHS says such violations dropped 42 percent in Oxnard, Calif., and 44 percent in Fairfax, Va., after red-light cameras were introduced. Injury crashed as Oxnard intersections with traffic signals declined 29 percent. In both cities, there was a spillover effect; violations and crashes dropped not only at intersections where the cameras were installed, but also at other junctions. A NHTSA pilot program reduced red-light running in 28 of 31 target communities. Based on preliminary results of programs in three areas, the Federal Highway Administration said photo radar should reduce red-light violations by 20 percent to 60 percent.

A poll conducted for the Advocates for Highway and Auto Safety in 1998 showed that 65 percent of the public supports use of red-light cameras; this increased to 74 percent in a 1999 poll. However, only 12 states and the District of Columbia allow such cameras. The Advocates and other groups are promoting legislation that would permit red-light cameras in other states. State Farm supports this type of legislation.

Solving the problem of driveways contributing to crashes because they are too close to intersections. This can be done by consolidating driveways; closing them; moving them as far back from the intersection as possible; and planning future driveways to minimize interference with traffic flow at the intersection.

Do "fixes" work?

What happens when specific intersections are targeted for improvement? Do crashes actually drop? Two pioneering projects of this type indicate they do: Three Detroit intersections were selected for upgrading in a project sponsored by AAA Michigan and Wayne State University. Fifteen months after the improvements were completed, crashes were down 39 percent to 48 percent -- and injury crashes were reduced 34 percent to 70 percent.

An improvement program at six intersections in Vancouver -- funded by the Insurance Corporation of British Columbia -- reduced rear-end collisions up to 40 percent.

State Farm wants to encourage a widespread expansion of this type of activity. That's why the company has a project aimed at making intersections safer and reducing the number of crashes, deaths and injuries that occur at them.

It began in June 1999 with the announcement of the 10 most dangerous intersections in the United States, based on State Farm's 1998 claim data and the percentage of vehicles insured by the company in areas in which these intersections are located.

State Farm offered up to $100,000 for improvements at each of these 10 intersections. In addition, the company said it would provide up to $20,000 for professional engineering studies of each intersection that made a "most dangerous" list in an individual state or province.

By June 2001, studies either were ongoing or had been completed at about 100 of the 172 intersections that were on State Farm's 1999 state and provincial lists. The company expected to provide about $2.4 million for studies and intersection improvements.

State Farm has now announced new lists of most dangerous intersections in the United States and many states and other jurisdictions, based on its 1999 and 2000 claim data and taking into account the severity of crashes, including injuries and amount of damage to vehicles. It expects to provide more than $5 million for studies and improvements on these intersections.

Over the last four decades, State Farm has initiated or supported numerous measures designed to reduce the damage to people and cars that results from crashes. This includes eliminating roadside hazards; encouraging use of seat belts; getting air bags into cars; improving car head restraints; and looking at ways to reduce deaths and injuries of children in crashes. Safety improvements are among the factors that help insurance companies control premiums. State Farm was able to reduce its auto insurance premiums almost $2.7 billion in 1998-2000. The company also returned about $2.6 billion in dividends to its customers between 1997 and 2000.

Funding the upgrading of intersections is consistent with State Farm's past support of car and road safety. The company also hopes to support local officials in their efforts to determine intersection upgrading they can do on their own.

What can drivers do?

But it's not a problem that only traffic safety experts can solve. You, the driver, can do your part to help reduce intersection crashes. For example: Don't speed through intersections. Look in each direction before proceeding.

Watch out for drivers trying to beat the signal change.

Know how the rules of the road apply at intersections -- who has the right-of-way at a four-way stop, for example.

Don't follow other vehicles too closely (they may stop suddenly).

Remember to watch for pedestrians and cyclists.

Signal your turns and lane changes. Never change lanes in an intersection. Make sure you are in the correct lane well before you must turn.

Don't try a left turn in the face of oncoming traffic unless you're sure you can do it safely. Don't disobey signs or signals that restrict turns.

Don't turn right on a red light unless you can do so safely.

Don't try to "beat" signal changes; a driver on the cross street may jump the gun.

Watch for emergency vehicles and funeral processions. Beware of motorcycles, which are often hidden by blind spots.

While waiting to turn, keep your wheels straight to avoid being pushed into another lane if you are hit from behind.

Don't enter an intersection if traffic is backed up on the other side. You might not be able to clear the intersection before the light changes and you'll be stuck in the middle.

In bad weather, be aware of slick pavement; adjust your speed so you'll have more time to stop if necessary.

Intersection safety tips

State Farm Insurance, the nation's largest auto insurer, says about one-third of all crashes happen at intersections. And a significant number of them are deadly. The National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) counted 8,814 fatal crashes at or near intersections in 1999 -- about 23 percent of all fatal crashes in the nation.

When approaching an intersection: Try to enter the correct lane for your intended action well in advance of reaching an intersection. Be sure to signal before changing lanes.

Watch for caution signs warning you of special circumstances at intersections such as turn restrictions, pedestrian crossings, or construction. Signs get knocked down, so beware of the drivers ahead of you.

Watch for other vehicles changing lanes abruptly. Sideswipe collisions are common around intersections. Stay out of other drivers "blind spot" where they can't see you in the rear- and side-view mirrors.

Maintain a safe distance between your car and the vehicle in front of you. Rear-end crashes are also very common near intersections.

Be alert to brake lights or turn signals beyond the vehicle ahead of you.

Anticipate when others will slow down.

After checking to your left when turning right, always look ahead and right before accelerating. Vehicles ahead of you may stop for pedestrians crossing the street. This is a very common rear-end crash.

Watch for pedestrians in all directions before making a turn at an intersection. Also, keep an eye out for cyclists going straight through the intersection, either on your right or on the sidewalk.

Don't adjust your radio or stereo, dial your cell phone, or be distracted by other things when entering an intersection. Inattention is a common cause of crashes.

If vehicles are stopped at an intersection with no signs, use extra caution when approaching them. They are usually stopped for a good reason.

Don't tailgate. You never know when the person ahead may turn or stop when approaching an intersection. Tailgating behind large trucks is especially hazardous. You can't see around them, nor can you see traffic signals ahead. You may enter the signal during the red phase.

When crossing an intersection: Watch for cross-traffic. Running a red light, intentionally or not, is a leading cause of intersection crashes.

Be alert to traffic from the opposite direction turning across your lane in an intersection. Even though you may have the right of way, some intersections allow left-turns without a green arrow.

Don't race a yellow light. Don't assume you are safe crossing on a yellow light.

Always stop behind the marked stop line or crosswalk. Keep your wheels straight and your foot on the brake while you wait.

Don't enter an intersection if traffic is backed up on the other side. You may get stuck in the middle of the intersection if the traffic doesn't move.

Don't change lanes while driving through the intersection. If you are not in the correct lane before entering the intersection, change lanes after you have cleared the intersection.

Treat a non-functional traffic signal as an "all-way stop." When you get to your destination, be a good neighbor and call local officials about the disabled signal.

1st TSG (A) tip: AVOID THE MOST DANGEROUS INTERSECTIONS BY ROUTE PLANNING!

LEADERSHIP that cares would take these actions NOW.

FEEDBACK!!!

Senator_Max_Cleland@cleland.senate.gov (Senator Max Cleland)

Thanks again for writing and for your input".

"Thank you for your e-mail. I appreciate having the benefit your

views on road safety and I do understand your position. Please

be assured that I will consider your thoughts.

Sincerely,

Max-

Return to U.S. Army Airborne Equipment Shop

Return to U.S. Army Airborne Equipment Shop