UPDATED 12 September 2009

THE NUCLEAR ERA -- SOVIET AIRBORNE DEVELOPMENT (1953 - 1968)

In the second post-war period of Soviet Airborne development, nuclear warfare dominated Soviet thought. This period extends roughly from the time of Stalin's death (1953) to the end of the sixties, when the Soviet pendulum swung back toward non-nuclear conventional war.

Based on the premise that a future war would begin with a nuclear exchange, the Soviets shifted from the large concentrations of forces used in World War II to smaller, more mobile forces. The smaller forces would be less of a target in a nuclear environment, while mobile forces would be better able to rapidly exploit the effects of nuclear weapons use. They proceeded to mechanize and motorize all elements of the force, tailoring them to fight and survive in an atomic environment.(7) Their weapons development resulted in a new generation of tanks (T-55 and T-62), artillery, air defense artillery and vehicles. Simultaneously, Soviet theorists began to tailor operational Airborne employment concepts to this new vision of nuclear war.

Accepting the premise that general war would likely begin with a nuclear exchange, the Soviets greatly expanded the mission of their Airborne forces. The perceived a gap in the time between the execution of a nuclear strike and the time when the ground units could reach the target area. Airborne forces would be used to close this gap. The rapid insertion of Airborne forces, immediately following nuclear strikes, would be used either to seize and hold objectives or to quickly destroy enemy forces remaining in the target area. With this fundamental change in mission, the Airborne forces would have to be more lethal, mobile and survivable than they were in World War II.

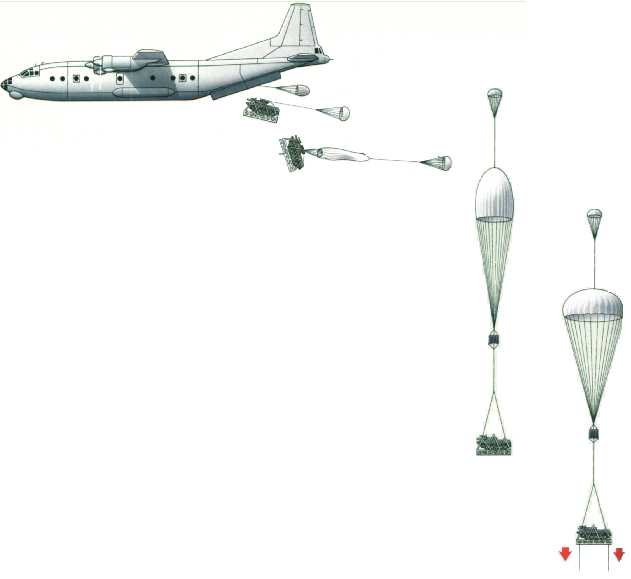

Recognizing the fact that the Airborne potential for increased mobility and survivability was limited by the lack of adequate transport aircraft, the Soviet Military Transport Aviations (VTA) created the first true assault aircraft, the Antonov AN-8 Camp. The AN-8 Camp, fielded in 1956, was equipped with a large rear-loading door and tail gun turret. The aircraft was estimated to have a combat range of 2,000 miles and capable of carrying about 50 troops.(8) The airlift capability of the VTA was further enhanced by the fielding of the AN-12 Cub in 1961 and the AN-22 Cock in 1965. The An-12 Cub, similar in size and capacity to the U.S. C-130 Hercules, can transport over 44,000 pounds of equipment or 80 Paratroopers and is still in service. The AN-22 Cock was designed primarily to transport outsized cargo and, with its 176,000 pound payload capacity, has substantially increased the airlift capability of the VTA. (9) With the development of these transport aircraft, the severe equipment weight limitations, imposed on the Airborne since their inception, were greatly minimized. The Soviets could now focus on the development of equipment required by the Airborne to accomplish their expanded mission: to rapidly exploit the effects of nuclear strikes.

It is important to understand that the Soviet development of Airborne forces was directly shaped and influenced by detailed analysis of their historical experience. Using the results of this detailed historical analysis, and "based on their perceptions of future war, the Soviets designed the force structure and equipment necessary to implement their ideas." (10)

[Editor: In contrast we have suffered from WWII victory-disease resulting in a smug attitude often unwilling to innovate]

An indication of where-the Soviets were going with their Airborne forces appeared in the 1966 issue of Military Thought which stated,

"troops which constitute the [Airborne] force need the same qualities which are inherent in the troops attacking from the front: a high degree of maneuverability and the possession of all types of weapons, equipment and material means."

It is here that the Soviet evolution of their Airborne forces has differed most from the U.S. For all the Airborne forces dropped during World War II, "maneuver was largely at the speed of the infantryman, [As it still is in the U.S. however,] Soviet recognition of this inherent weakness has been the key to the further development of their [Airborne] forces." (12) The Soviet concept of the Airborne assault has the landing of the force as simply the beginning of the operation. Secondary mobility, the ability of the assault troops to maneuver after the airdrop, is the essential capability that will justify the significant expenditure of resources required to execute an Airborne operational

The Soviets' earliest attempt to solve the secondary mobility problem of the Airborne came with the introduction of the ASU-57 assault gun in 1957. This vehicle, designed "specifically" for the Airborne, has a 57-mm gun and a troop compartment aft for six personnel. Limited secondary mobility for the Airborne infantry troops was now possible. A few years later the ASU-85 assault gun, again designed specifically for the Airborne forces with an antitank capability, the ASU-85 also enhanced their secondary mobility as Paratroopers were routinely transported on the outside of the hull. (14) These two systems, the ASU-57 and the ASU-85, were organized into assault-gun battalions in the early 1960s, one in each Airborne division. Along with the additional firepower provided by the RPU-16 towed multiple rocket launcher and the air defense provided by the ZU-23, the Airborne Division was in much better shape to accomplish its mission of rapidly exploiting nuclear strikes. Although, by the late 1960s the Soviets had begun to reconsider their "single option" of fighting a nuclear war, it was clear that Soviet thought regarding operational Airborne employment was transitioning from passive, static missions to concepts based on maneuver.

CONTEMPORARY SOVIET AIRBORNE DEVELOPMENT (1968 - 1988)

As noted above, with the appearance of nuclear weapons, the importance of the Airborne troops to the Soviets significantly increased. The unique ability of these troops to rapidly exploit the results of nuclear strikes motivated the Soviets to commit tremendous amounts of research, time and money into the modernization of their Airborne forces. However, following Khrushchev's fall from power, the Soviets assessed Khrushchev's "single-option" nuclear strategy and decided that conventional war without nuclear weapons use was possible.

Starting in the early 1970s, the Soviets prepared themselves for a conventional war with the possibility of nuclear escalation, the equivalent of war in a "nuclear-scarred" environment. This was the Soviets' version of the "flexible response." (15) The switch from nuclear to conventional operations had serious implications for the Soviet Airborne forces. The Airborne troops continue to have, as an important mission, the destruction of enemy nuclear resources. However, the Soviets believed that without the use of nuclear weapons to suppress enemy air defenses and disrupt the enemy's mobile reserves, an Airborne operation onto a well defended objective would be impossible. (16)

With the change of strategy toward conventional war, the Soviets determined that their conventional forces, lightened to permit the rapid exploitation of nuclear strikes, needed to be strengthened. The new emphasis produced a surge in technology as new equipment was fielded to increase the combat power of the conventional units. New generations of tanks, artillery, rockets, missiles and a true infantry fighting vehicle (the BMP) appeared. The expanding ground forces grew in size and, although still tank heavy, reflected the combined arms balance necessary for success in a conventional war. All Divisions grew in manpower and mobility with mechanized infantry, artillery and tank improvements. (17)

The conventional war environment also surfaced a new Soviet concern, the need for depth. The Airborne forces could provide the Soviets this deep attack capability, along with the newly formed forward detachments and operational maneuver groups[OMGs]. Large-scale deep strike Airborne operations, of operational or strategic significance, would now be available for use in a theater offensive.

For the theorists, the primary concern for the Airborne forces was the issue of survivability in a more lethal environment, especially without the benefit of the support of nuclear weapons. (18) Without the

nuclear weapons to suppress the air defenses and interdict the enemy's mobile reserves, the ability of the Airborne to accomplish their mission was questionable. Furthermore, the expanded role of the Airborne also put less emphasis on the requirement for a quick linkup with a ground force at some point after landing, further risking their survivability. It was clear that to accomplish their expanded mission, the Airborne forces required greater firepower, protection and mobility.

Hereafter, drops would have to be made in weakly held or vacant sectors of the enemy rear, with quick overland strike against the target. Without fuller mechanization of these forces these tactics would be impractical. In addition, large static formations of Airborne troops would make a tempting target for enemy nuclear forces. To survive, the (Airborne forces) would have to remain dispersed and mobile, concentrating only for the assault, reinforcing the need for a mechanized Airborne division.(19)

The requirement to react to the enemy's armored, mobile counterattack forces, further detailed the need for heavier antiarmor firepower and equivalent mobility in the Airborne forces. These collective requirements led to the development of the BMD (Boevaia Mashina Desantnaia -- landing combat vehicle), an Airborne infantry fighting vehicle, designed specifically for the Airborne forces. The BMD may be the most important improvement of Airborne equipment and armament in the history of the Airborne.

The BMD, tested in 1970 and revealed to the public in 1973, is an armored, amphibious vehicle capable of being airdropped by multi-parachute or parachute retro-rocket system.

[BMD-1] and was initially armed with a 73-mm smoothbore gun, a Sagger antitank guided missile and three machine guns (two bow-mounted and one coaxial). It carries an Airborne squad of up to seven men, counting the driver, and has a cruising range of 320 kilometers. (20)

[Editor's note: since the author has written, the BMD-2 model has entered service with a stabilized 30mm auto-cannon and better signature-less ATGMs mounted. The BMD-3 is also being introduced. Russian Paratroops exit the FRONT of IL-76 aircraft while their BMDs simultaneously heavy drop out the rear ramp, resulting in a tighter and faster forming up on the ground. This is possible since their parachutes do not use static-lines trailing deployment bags that would get sucked into the IL-76's engines---upon exit Russian Paratroops have a small drogue chute open to stabilize their body upright for a short freefall and delayed opening of their round canopy automatically with manual rip-cord back-up.

The Soviets have been quite specific about the importance of the BMD. In 1977, Army General V.F. Margelov noted how the BMDs "greatly increased the maneuver capabilities of units on the battlefield and opened broad possibilities for the full mechanization of the force" (21) From the Soviets' view the BMD radically changed the nature of Airborne operations. The BMD allows Airborne battalions to drop on several smaller drop zones, widely separated and away from their objective. These battalions can then assemble, as a regiment or even as a division, away from the objective, greatly increasing their security and survivability. (22) The forces could even attack the objective simultaneously, from several different directions.

Initially, a company of 14 BMDs was attached to every rifle battalion, providing mobility to one-third of the division's rifle squads (23).

[Editor: EXACTLY what we propose be done to one company in one rifle battalion in each of the 82nd Airborne Division's Ready Brigades: 14 M113A3 Gavins as a start towards operational maneuver capabilities, and to fill the shock action vacuum when the M551 Sheridan and M8 Buford Armored Gun System light tanks were taken away or not purchased as promised.]

However, by 1980, the Soviets had decided that a one-third mobile Airborne division was still two-thirds foot mobile and went to the full mechanization of their Airborne divisions. The result is an Airborne Division clearly more comparable to a mechanized or light armored unit than to an [light] Infantry Division. With the increase in their secondary mobility the Soviets also worked to increase the firepower of their Airborne forces. Besides the significant increase in firepower that accompanied the addition of the 348 BMDs per Division and their mounted weapon systems, the Soviets have also modernized the rest of their combined arms team. Several variants of the BMD[-2] have had their AT-3 Sagger replaced by the AT-4 Spigot or AT-5 Spandrel, and a limited number [Editor: now all BMD-2s] have also had their 73-mm gun replaced by the long-barreled 2A42 30-mm [auto-] cannon. (24) In the artillery,

[Editor: Our Airborne's 105mm and 155mm towed howitzers can direct-fire, too, but do not have gunshields or anti-tank rounds for this purpose]

The M1975, 122-mm multiple rocket launcher, mounted on a GAZ-66 light truck, has replaced the old towed 140-mm system.

[Editor: the U.S. Airborne IS getting a MLRS 270mm rocket pod on a 5-ton FMTV truck called HIMARS to redress our artillery disadvantage

However, the most recent change to the Airborne artillery has come with the introduction of the 2S9, a 120-mm self-propelled howitzer, mounted on a BMD chassis and replacing the [hand-loaded, indirect-fire-only] M-1943 120-mm mortar in the Airborne battalions.

[Editor: we can get a 120mm direct/indirect fire capability on a light air-droppable vehicle using the M113A3.

The 2S9 is also capable of replacing the D-30 122-mm towed howitzer in the artillery regiments, and the ASU-85 assault gun in the assault gun battalion. (26) The ten kilometer range and anti-tank capability of the 2S9 provides a quantum leap in capability for the Airborne division. (27) The significance of this trend toward self-propelled mobility is that by eliminating many of the [wheeled vehicle] prime movers, the Soviet Airborne is benefiting from a substantial increase in firepower without increasing their overall airlift requirements. (28)

Concurrent with the evolution of the Airborne forces, the Soviets worked extensively on the development of helicopter operations. Study and experience highlighted the vulnerability of forces parachuted into combat. So, as early as the 1950s, the helicopter was considered as an alternate means of insertion. Experiments with helicopters began in the mid-1960s and with the added lift provided by the Yak-24 Horse, the MI-6 Hook and the MI-10 Harke in the late 1950s, the helicopter seemed better suited to perform some of the missions previously performed by the Airborne troops. (29)

By 1960, tactical experimentation and the impressive increase in the Soviet helicopters' lift capabilities convinced the Soviets of the efficiency of air assault operations. Exercises involving helicopter-lifted forces increased. Air assault forces were used to maintain the tempo of the advance and could be used

to quickly cross water obstacles, defiles or to seize key terrain behind enemy lines. Their use in the 1967 Dnepr exercise included, for the first time, the use of U.S. Vietnam style door guns and rocket pods for clearing the landing zone. (30) The addition of two new helicopters to the Soviet inventory in the 1970s, further confirmed their commitment to helicopter operations. The MI-8 Hip troop transport and the MI-24 Hind attack helicopter provided both an increased lift capability and the accompanying fire support needed for successful Air assault operations. Until the late 1960s, Soviet Air assault theory stated that Airborne troops, by virtue of their training in operations behind the enemy lines, were best qualified for helicopter assault operations. However, in the 1970s the Soviets switched to the view that ordinary motor rifle troops could be used as Air assault forces instead of Airborne troops. (31) This probably reflects the Soviets' analysis of the American experience with large-scale air assault operations in Vietnam.

Also in the 1970s, the Soviets introduced a new unit into their force structure - the Air assault Brigade. These specialized Air assault brigades, created as front level assets, contain both Airborne and Air Assault units and are capable of both tactical and operational level missions. (32) The Soviets' current Air assault concepts provide for the use of helicopter operations, in lieu of Airborne operations, at the tactical level and have helped focus their Airborne development toward the operational and strategic level missions that only Airborne forces are capable of performing.

However, it took the continued modernization of the VTA to enable the Airborne forces to project their power at the operational and strategic level. The Soviet airlift modernization efforts continued with the fielding of the IL-76 Candid in the early 1970s and the AN-24 Condor in the mid-1980s. The IL-76 Candid is similar in size to the

U.S. C-141 Starlifter and capable of carrying three BMDs or 125 Paratroops. The AN-124 Condor is capable of airlifting over 330,000 pounds (compared to the U.S.'s C-5 Galaxy payload of 290,000 pounds) or 320 Paratroops (compared to 155 Paratroops in the C-141 Starlifter). Finally, the newest Soviet airlifter, the AN-2225 Mechta, fielded in 1989, is the largest aircraft ever made, with a payload of over 500,000 pounds. Additionally, the VTA continues to improve its airlift capability by producing over 50 new airlift aircraft each year, mostly IL-76 Candids. In contrast, the U.S. has produced less than 50 airlift aircraft in the next four years-assuming the C-17 is funded and fielded as planned.

Not only have the Soviets modernized their Airborne forces and their airlift forces, but they have also demonstrated the willingness to commit these strategic forces, first in Czechhoslovakia in 1968 and then in Afghanistan in 1979. The Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia highlighted the Soviets' potential for large-scale Airborne troop employment in a force projection role. The Airborne division, which spearheaded spearhead the invasion of Afghanistan. This time a BMD-equipped Airborne force of division-size landed in Kabul and moved quickly to seize key points in the city. Kabul was secured in one day. (34) Although able to air land in both cases, these forces were well prepared, and equipped to conduct a forced entry if required.