GAVIN'S PARATROOPERS : THE TYPE OF MEN

UPDATED 1 August 2012

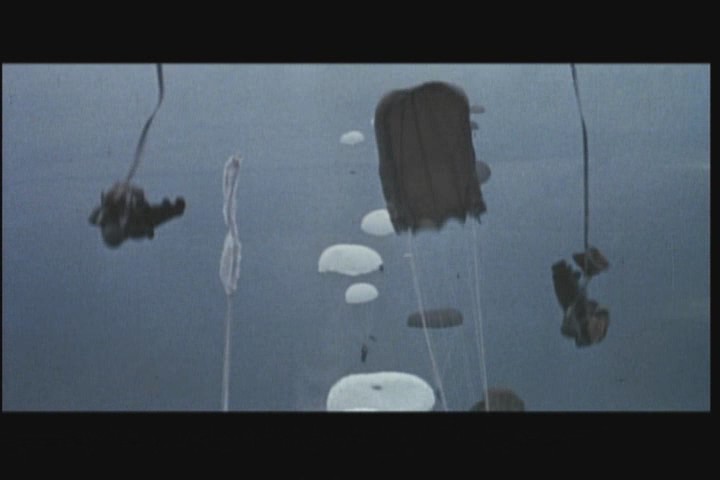

Actual Video clip of U.S. Army Paratroopers exiting a C-141B Starlifter

Actual Video clip of a C-130 Hercules combat equipment jump

youtube.com/watch?v=1nk5doxubyg

youtube.com/watch?v=1nk5doxubyg

THE RULE OF LGOPs

(LGOP = Little Groups of Paratroopers)

After the demise of the best Airborne plan, a most terrifying effect occurs on the battlefield. This effect is known as the rule of the LGOPs. This is, in its purest form, small groups of pissed-off 19-year-old American Paratroopers. They are well-trained, armed-to-the-teeth and lack serious adult supervision. They collectively remember the Commander's intent as "March to the sound of the guns and kill anyone who is not dressed like you..."

...or something like that. Happily they go about the day's work........

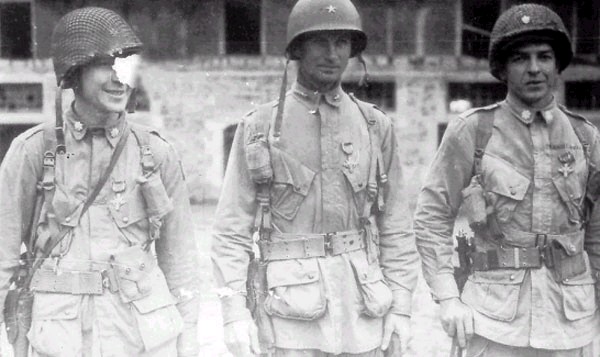

"Show me a man who will jump out of an airplane, and I'll show you a man who'll fight."--General James M. Gavin

"American Parachutists...devils in baggy pants...are less than 100 meters from my outpost line. I can't sleep at night; they pop up from nowhere and we never know when or how they will strike next. Seems like the black-hearted devils are everywhere..."

(An entry in a German officer's diary found after the Battle of Anzio)

Movie Trailer

youtube.com/watch?v=DKDPX8PEiVk

youtube.com/watch?v=DKDPX8PEiVk

NEW!

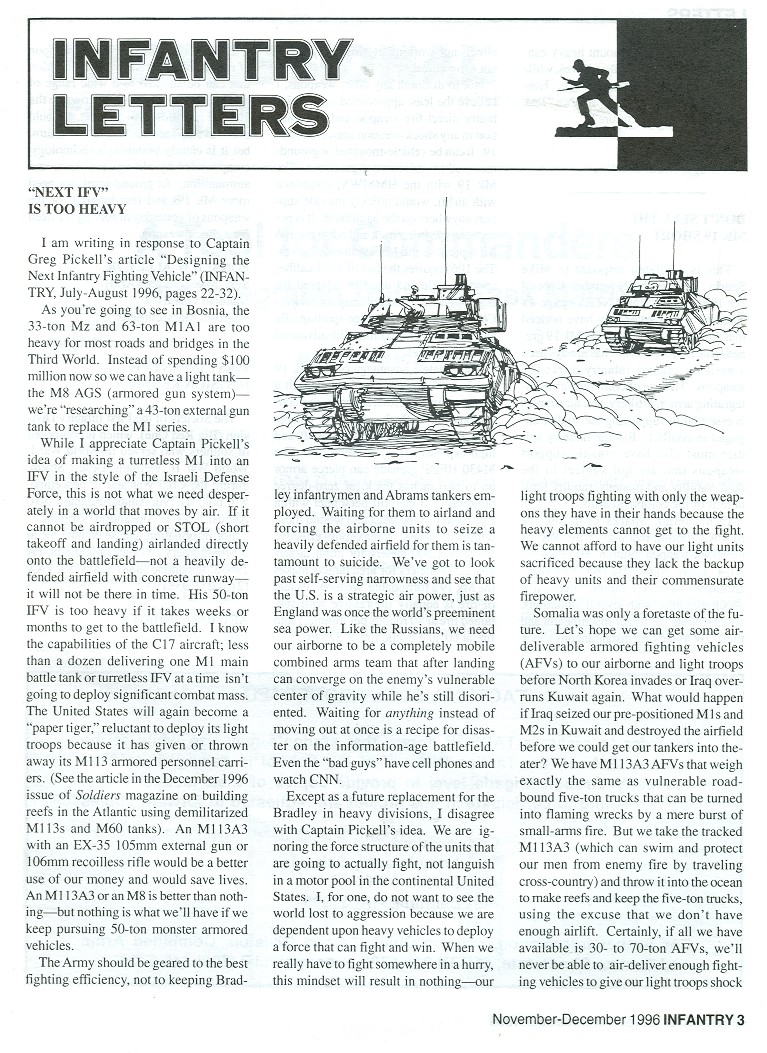

"Individuals had to be capable of fighting at once against any opposition they met on landing. Although every effort was being made to develop the communications and techniques to permit battalions, companies, and platoons to organize promptly, we had to train our individuals to fight for hours and days, if necessary, without being part of a formal organization. Equipment had to be lightweight and readily transportable....Since the beginning of recorded history, Soldiers have been drilled repetively to de-emphasize their individual behavioral traits and force them to adapt to larger combat formations. Perhaps the greatest efficiency in transforming each individual, squad, platoon, and so forth into a cog in a larger machine was demonstrated in the armies of Frederick the Great, and although machine weapons had changed all this, between World War I and World War II countless hours were spent on wheeling about and moving squads to the right and to the left, as though they were preparing to fight the wars of a century ago.All this had to be discarded as we sought to train the Paratroopers to the highest peak of individual pride and skill. It was at this time that the use of nameplates was adopted, the purpose being to emphasize the importance of an individual's personality and reputation. To the Soldiers of another generation, it seemed to suggest too little discipline and too much initiative given to individual Soldiers. We were willing to take a chance that this would not have a disrupting effect on larger formations. It did not, and there were many occasions in combat when the Paratroop officers, and NCOs effectively took over the command of larger formations of other units. Aside from the impact of this type of training on the Airborne formations themselves, it had a tremendous significance to the Army as a whole. The morale of the Airborne units soared, especially after their first combat, when they could see for themselves the results of their training".

Are you of the "another generation" ilk? Wedded to obsolete traditions? Who says we have to use silly, useless D & C to instill fighting discipline in Soldiers? Why not in the field like Gavin did? Learning SERE skills? The usmc didn't even put nametapes on its individual member BDUs (camies) until after the Gulf War TV coverage embarrassed them into it. How about this for 19th century robotics?

Think about it.

"Zero defects" mentalities do not inspire the men to give their best, we must create an atmosphere where subordinates can use their personality and initiative to get the mission done. Mission-type orders not robotics. To win on the future, non-linear urbanized battlefield, where we had only just arrived within hours by AIR will require the Soldiership like that of Chamberlain and his men on Little Round top. These men must be able to communicate freely and truthfully without concern over their ego, peer status or career concerns.

"The Mongols, a classic example of an ancient force that fought according to cyberwar principles, were organized more like a network than a hierarchy. More recently, a relatively minor military power that defeated a great modern power--the combined forces of North Vietnam and the Viet Cong--operated in many respects more like a network than an institution; it even extended political- support networks abroad. In both cases, the Mongols and the Vietnamese, their defeated opponents were large institutions whose forces were designed to fight set-piece attritional battles.

To this may be added a further set of observations drawn from current events. Most adversaries that the United States and its allies face in the realm of low-intensity conflict, such as international terrorists, guerrilla insurgents, drug smuggling cartels, ethnic factions, as well as racial and tribal gangs, are all organized like networks (although their leadership may be quite hierarchical). Perhaps a reason that military (and police) institutions have difficulty engaging in low-intensity conflicts is because they are not meant to be fought by institutions. The lesson: Institutions can be defeated by networks, and it may take networks to counter networks. The future may belong to whoever masters the network form."

"Cyberwar is coming" (Scroll down to Selection 3) by John Arquilla and David Ronfeldt International Policy Department RAND

[Editor's note: These guys are right on target at the source of our temporary foreign policy "loss" in Vietnam 1975-1991(?). However, war is not just a lethal sporting contest among combatants, its about whose IDEAS will dominate, in the case of FREEDOM, in the end the truth has won out over communism. However, if the forces of freedom were more open-minded and "networked" like the John Paul Vann did until he died stopping the 1972 NVA invasion or the enemy in general did, we could have won the struggle sooner on the battlefield and not just wait for cultural changes to do it for us. The men who fought in Vietnam need to know that their sacrifices did count-just ask the people of Thailand. But if we are to learn from our war there, we must not make excuses that the politicians "did this or that" when there is plenty to do at our own level within the military to network and "out guerrilla the guerilla".]

A noted Army writer and tactician responds:

"Mike:Nationally syndicated columnist and decorated Army officer, retired Colonel David Hackworth writes:

It's interesting that the two great Army developments of WWII were Armored warfare and Airborne warfare. (We'll leave aside marines and SOF for the moment.) A field-trained individual who can play LGOP really works well.I sure do agree that all of that D & C and similar obsolete stuff serves little purpose. Guess it makes someone feel good..."

"Gavin was such a good Soldier. Thx Mike."

An Army weapons analyst and Lieutenant Colonel writes:

Later,"Most of the Airborne troops were very well trained infantry, first. They already went through the "depersonalizing and rebuilding" process so that they would be competent 'cogs of the machine.' Then, and only then, were they given special training to bring them to a higher level.

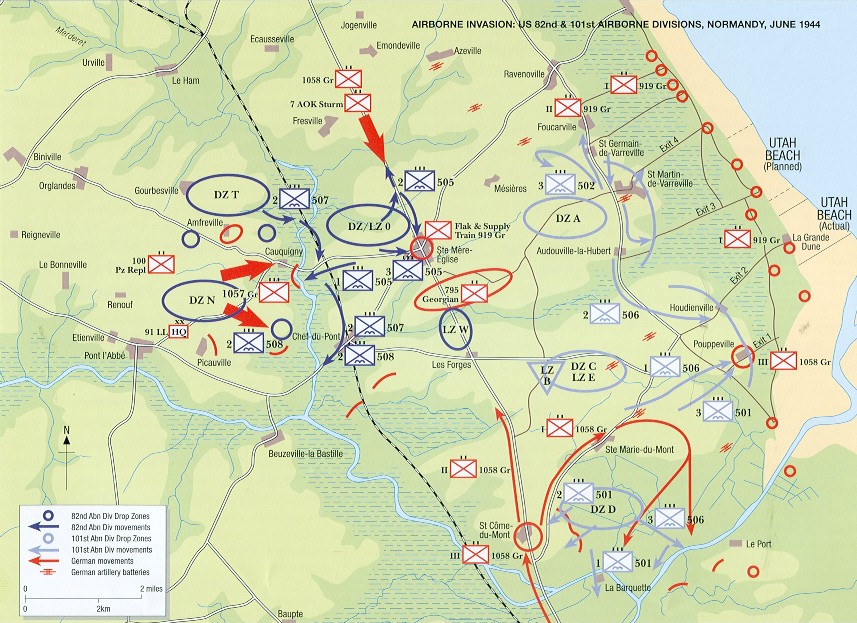

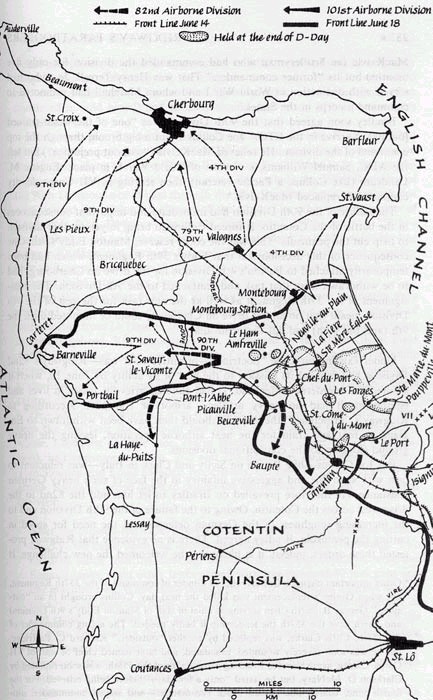

On another level, the Airborne WANTED to mirror a straight infantry division, with infantry regiments, divisional artillery, etc., etc. Their challenge was not only the lack of adequate communication, but the technical inability to to be consistently dropped in a cohesive formation at a specified drop zone. In practice, they were scattered and lost all over the battlefield and fought in little groupings of individuals and squads that wandered about until blundering and melding into ad hoc platoons and companies. Fortunately, such confused wandering also wreaked confusion upon the enemy, with reports and sightings coming in from EVERYWHERE!! This alone tied down considerable enemy forces, in addition to the troopers' sniping, ambushing, and other interdictions. Then, once the ground effort (which the Airborne drop was supporting) broke through for a linkup, all was forgotten in the glow of a successful operation (the ground effort)".

http://imabbs.army.mil/cmh-pg/104-13.htm

Airborne operations

army.mil/cmh-pg/documents/abnops/tabb.htm

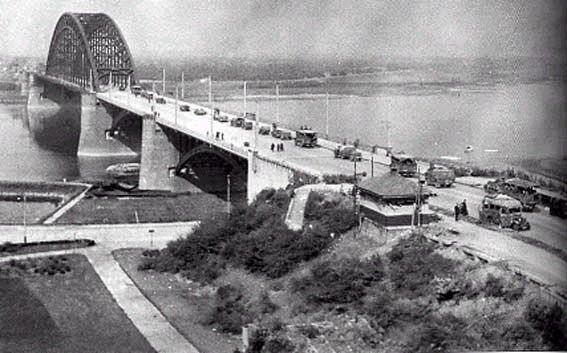

North Africa, Sicily, Normandy, and Eindhoven and Nijmegen

pim.nl/mg/pega1.htm

reocities.com/CapeCanaveral/Hangar/4602/kreta.htm

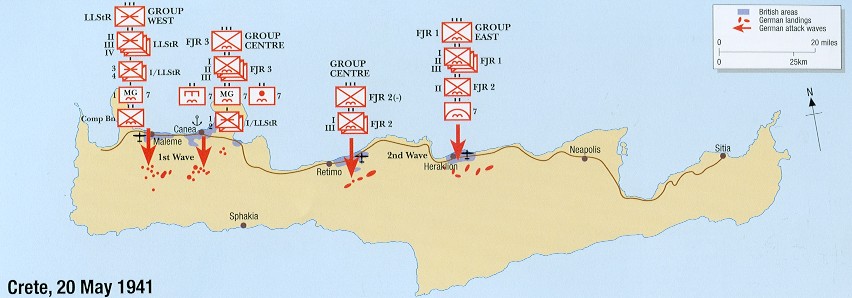

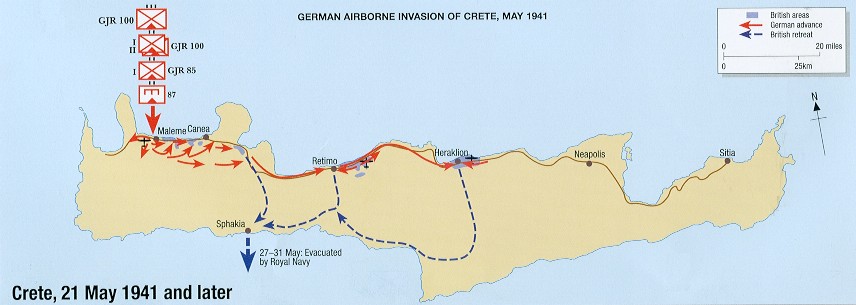

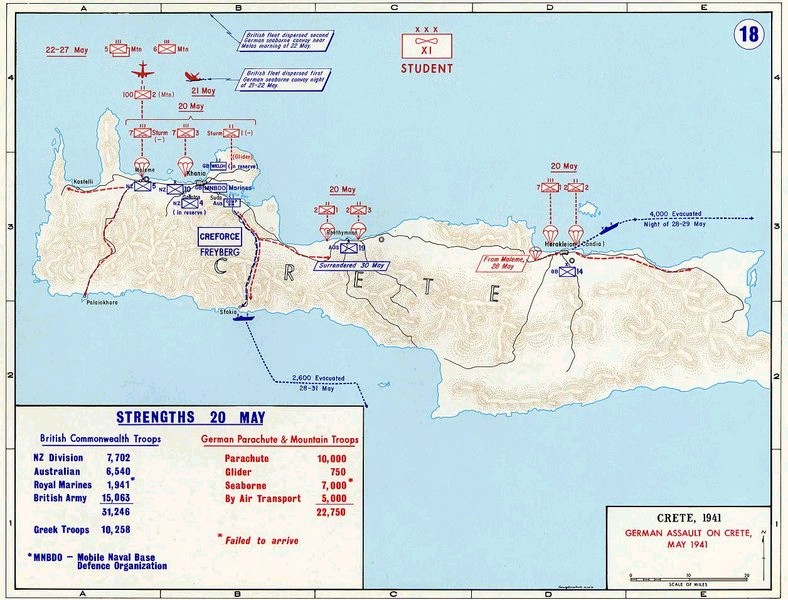

Crete

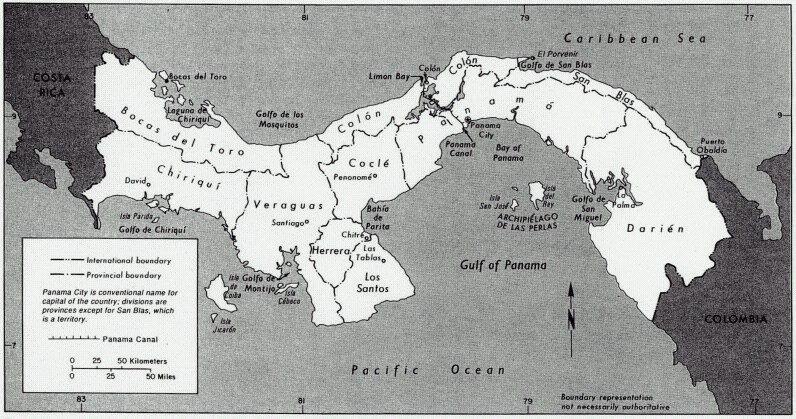

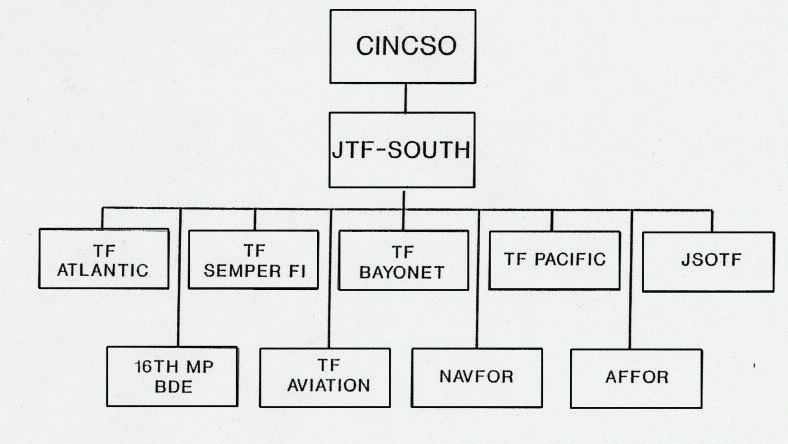

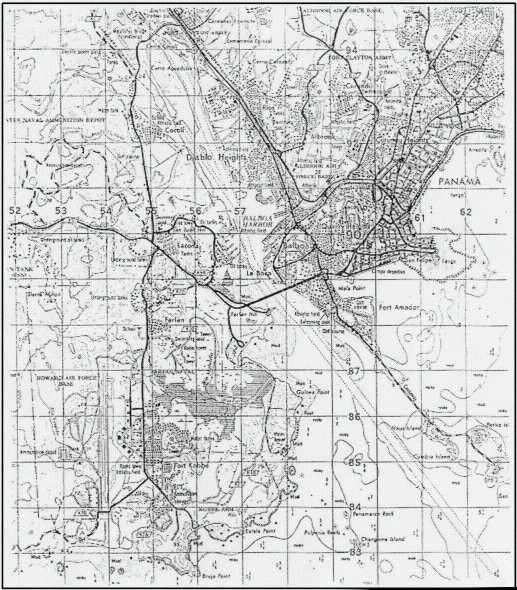

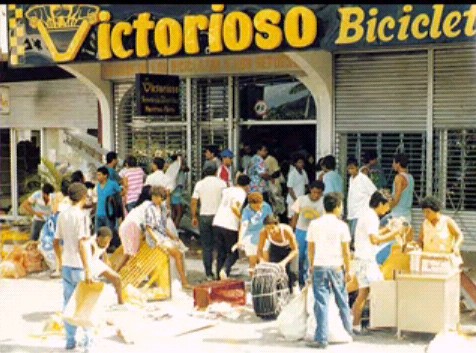

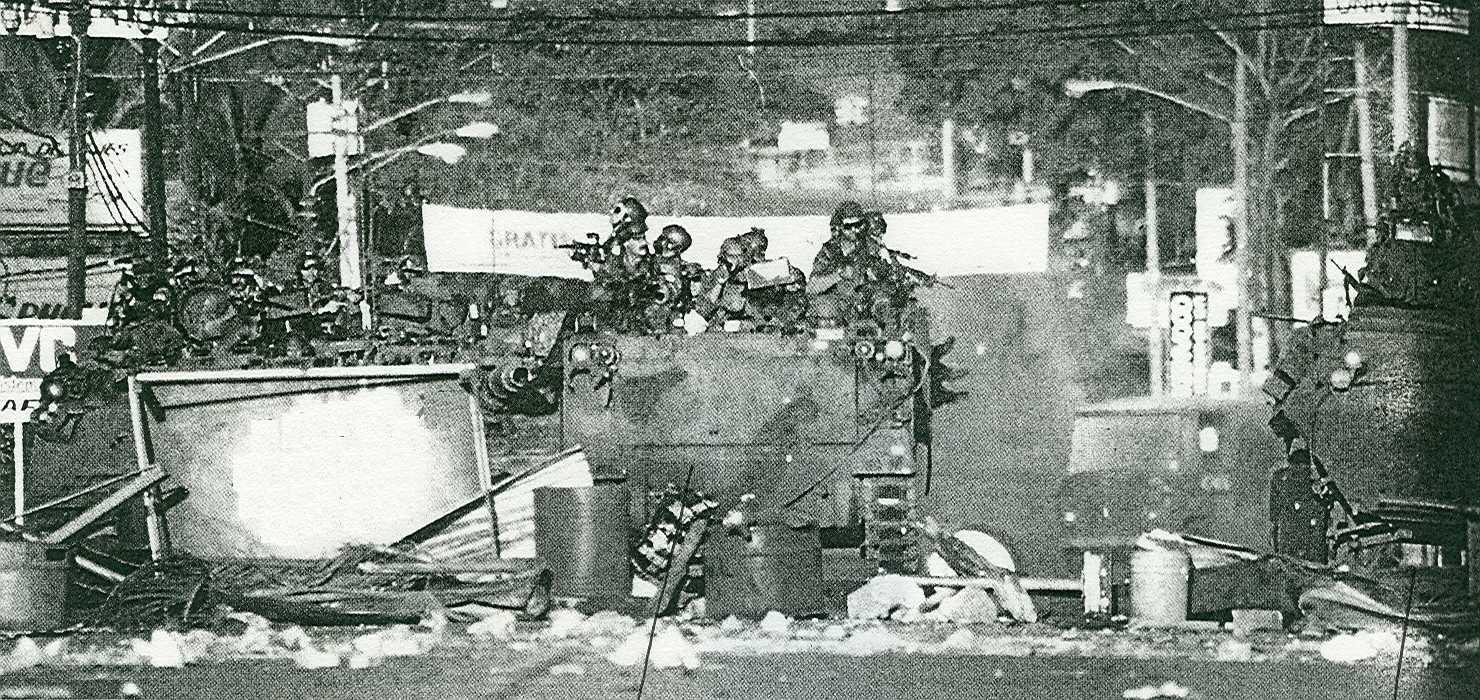

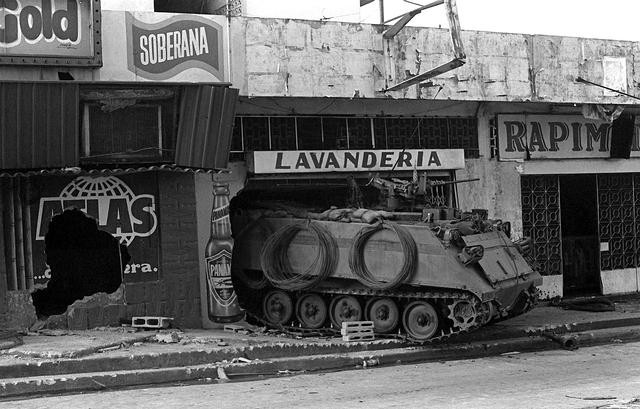

With today's technology jump delivery is very precise and Drop Zone selection can be done instantly from space and the air recon means. Crete was a costly victory for the Germans because of the "Ultra Secret" (German codes broken to reveal all classified messages) told the Allies exactly where their DZ and drop times were....yet the Allies were still pushed to the sea. It was still a victory and proof deep Airborne operations can work in spite of no amphibious forces around to help. If you click on the hypelink above or here on Crete, you'll see the Royal Navy sank the amphibious forces that the Allied Commander defending the island thought were necessary to win. He was wrong. Years later, on Grenada the same thing happened, the enemy expected sea attack from marines, but instead, the Rangers and 82nd Airborne came from long away and caught them by surprise. The invasion of Panama was a "deep" Airborne operation that worked as was The Russian seizure of Afghanistan and Czechoslovakia, though in the latter, ground forces were en route for link-up.

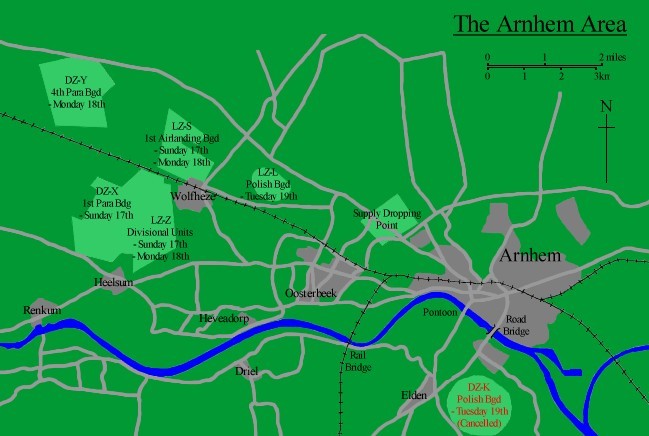

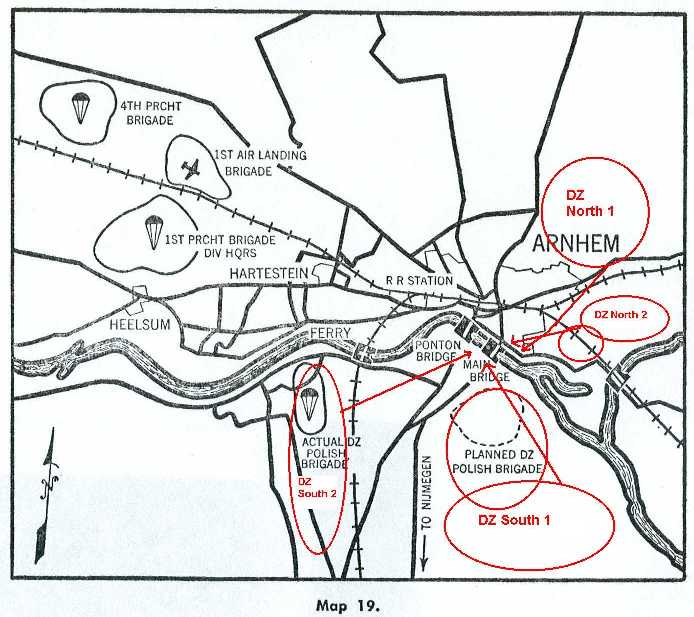

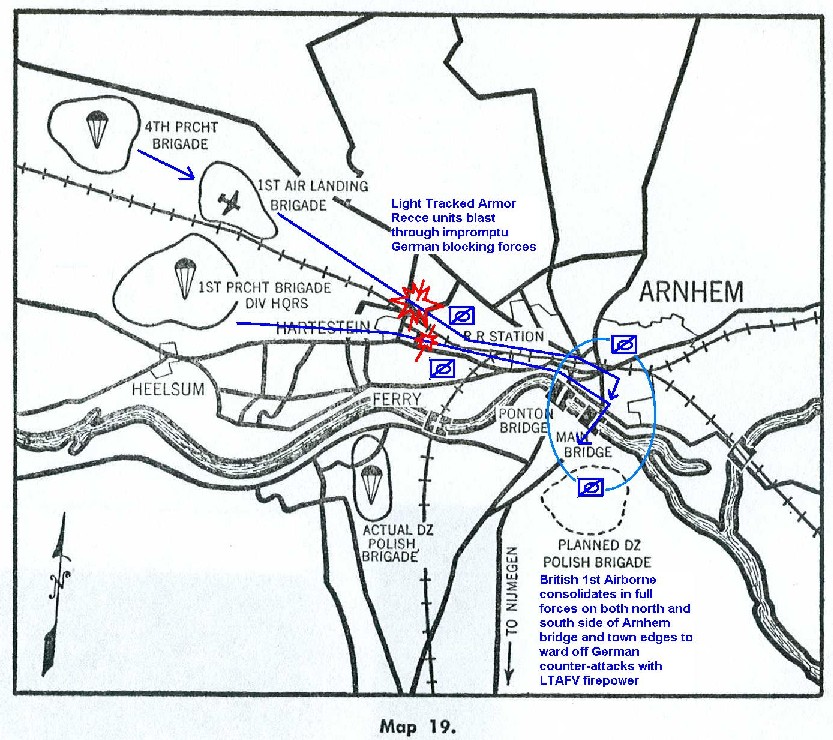

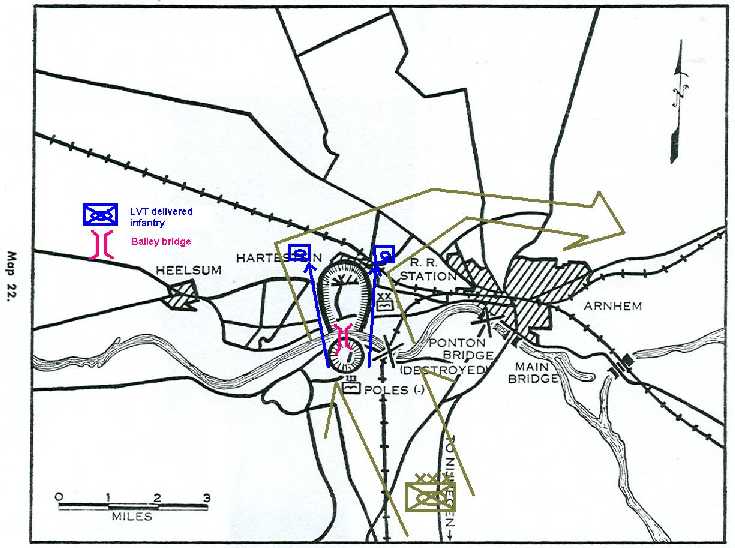

Had the British jumped south of Arnhem bridge, instead of 8 miles away at a 1 mph foot-slog, the entire battle would have been an undeniable Allied "deep" Airborne victory. Dien Bien Phu was a poorly selected firebase in the low ground, many other poorly defended positions have been over-ran that were established by ground and sea transport, also. In the Second Indo-China war, the U.S. set up better defended fire bases that were kept going by airdrop, most notably Khe Sanh. Deep airdrops of combat power can work, its what you do afterwards on the ground that is the key. If you sit still, the enemy is likely to gain the initiative whether you walked, flew or motored there. After the Paratrooper lands he must be MORE MOBILE than any enemy and that can be done by speed-marching, solving the Soldier's load, human powered vehicles and airdropped armor.

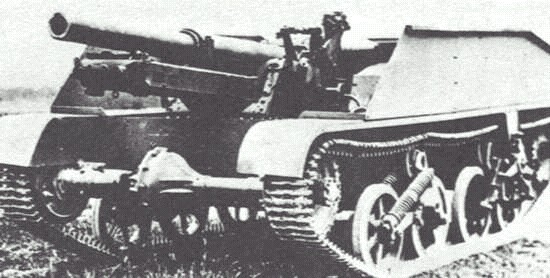

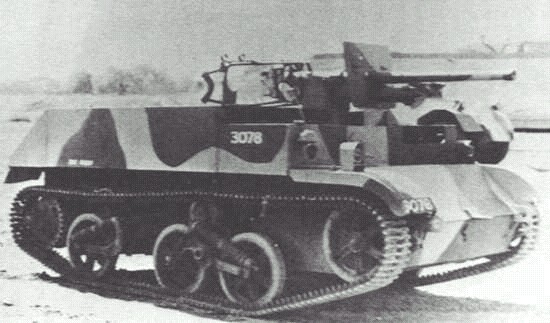

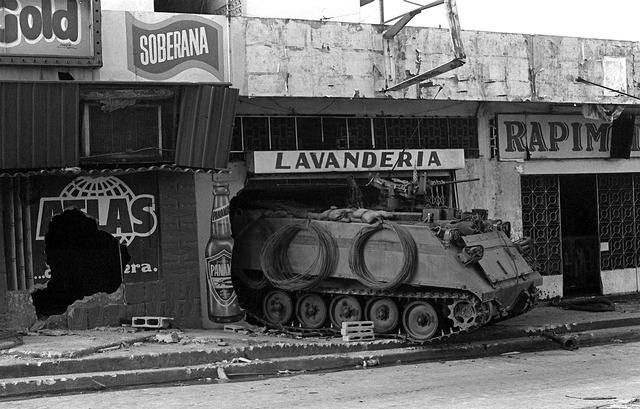

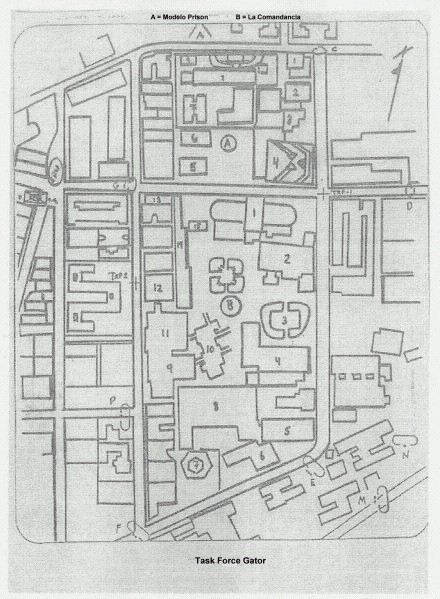

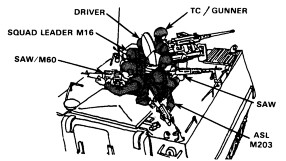

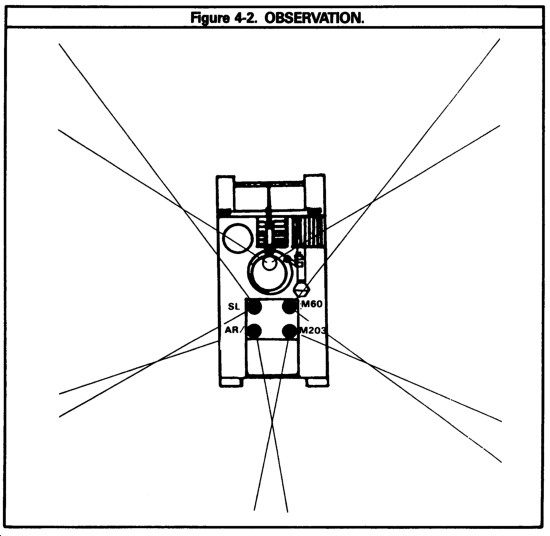

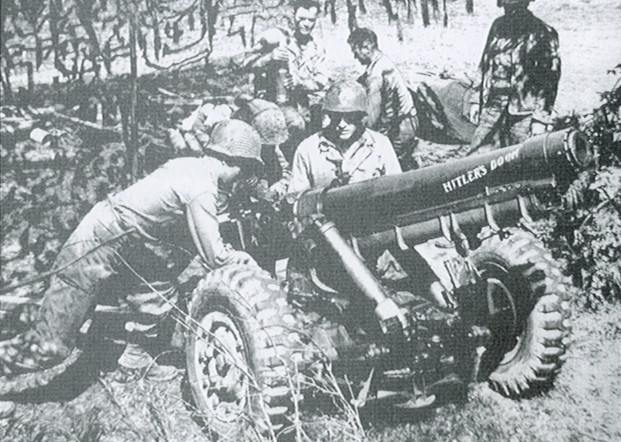

We are pushing hard for light Armored Fighting Vehicles (AFV aka TANKS) like the M113A3 Gavin and the M8 Ridgway Armored Gun System to be organic to the Airborne so it can fight actions like a Bostogne successfully and not end up like a 1943 "Cisterna" or 1993 "Somalia".

Good point about WWI: the U.S. Army Air Service was doing "Close Air Support" (CAS) to sweep the enemy during the 1918 offensives under the leadership of General Billy Mitchell personally directing the battles from SPAD XVI aircraft long before the usmc boasted "it invented CAS in the 1920s". By the end of the war, we were combining arms as we would have to do again in WWII.

"On the next day, before dawn, Pershing's main attack hit the Germans along the southern edge of the Saint-Mihiel salient while French Colonial troops under his command and the United States 4th Division pushed eastward from the salient's western edge. Overhead, our planes gave close air support and bombed and strafed supply installations and troop columns in the rear of the German lines. French tanks manned by Americans supported the infantry assaults. The United States Army's first modern battle had begun."Fighting Generals by Curt Anders, 1965, G.P. Putnam & Sons, NY

"Mike-

Interesting site. Thanks for showing me. Please keep me in mind for future areas of similar style. Although why anyone would want to jump out of a functional aircraft is still a mystery to me-"

XXXX XXXX

(Stillborne!)

God's design of the creation could easily be studied to find the principle of air resistance in action to gently descend from the air to the ground: leaves falling from a tree are a good example. It is believed that Chinese acrobats used parachute-like devices as long ago as 1306. The principle was recognized by several writers, and Leonardo da Vinci proposed the basic idea for parachutes in 1495. Leonardo da Vinci sketched a man-sized parachute with a man in mind to be lowered by it, even though no one had ever flown. He visualized it as a tool to escape from tall buildings and structures in event of fire. The dimensions he calculated as necessary to safely land a person 300 years before one was ever used are very close to the ones used today.

The first person to demonstrate the parachute in action was Louis-Sébastien Lenormand of France--in 1783 he jumped from a tower with two parasols. A few years later other French aeronauts jumped from balloons. André-Jacques Garnerin was the first to use a parachute regularly. He made a number of exhibition jumps, including one of about 8,000 feet (2,400 meters) in England in 1802.

In 1785, a French balloonist named Pierre Blanchard used a pet dog for his first idea of a parachute and dropped the dog several hundred feet, the dog ran off with the parachute and was never seen again.

In the 1800s, acrobats were dropping from balloons that resembled a parachute and a trapeze, they did this to liven up their act, because balloons got boring after awhile and they needed something else to keep the crowds interest, people watched mostly hoping to see a fatality.

The parachutes were rigid with stiffening rods to maintain there shape and tied to the bottom of the balloons, when it came time to jump a helper would cut the rope and they would ascend in their particular contraption.

It was an era of do it yourself designs some worked and some didn't. The ones that didn't were the unlucky ones (this could be considered an understatement).

One of the first parachutes was invented in 1837 by a man named Robert Cocking. Cocking developed a parachute like an upside umbrella, he felt being upside down it would control oscillations ( to bad he didn't know about an apex hole) He demonstrated in 1837 in England suspended from a balloon named Nassau, and piloted by Charles Green, who cut him loose.

The canopy was covered with linen and used stiffeners made of thin metal tubes to retain it's shape, the only trouble was it weighed 223 pounds . It worked fine at first, but the stiffening tubes started to give way , then a hole developed in the canopy, then it collapsed (it was the first parachute fatality).

After that England's interest in parachutes declined, but continued in America and Europe.

In 1884 the Baldwin Brothers developed a parachute similar to the one used today, it had no stiffeners, just a fabric canopy that was folded and stuffed into a soft container. The canopy was not attached to to the jumpers but to the balloons rigging and a harness was worn by the jumpers and attached to the chute, it was several years in development before they had a full size model and was first tested from 3000 ft, instead of being guinea pigs they used sand bags instead for the first drop, the parachute worked perfectly and they considered it a success.

They decided to demonstrate it publicly, and sold tickets for the event at Golden Gate Park in San Francisco, California on January 30, 1887. Thomas Baldwin the younger brother got elected for the task, the brothers took the balloon to 5,000 ft. before a sellout crowd.

Tom jumped and the chute worked perfectly opened within five seconds and he drifted slowly to the ground, and landed safely.

This do-it-yourself design also applied to airplanes with a lot of fatal results.

The Wright brothers finally got one to fly and it has been the "skies the limit" (Pilot, Engine, Airframe--PEA) every since, until the planes crash.

Now the interest in (and need for) parachutes really "took off".

Early parachutes were made of canvas, and later of silk. The first successful descent from an airplane was made by Capt. Albert Berry of the United States Army in 1912. In World War I, parachutes were used by observers to escape from captive balloons but were considered impractical for airplanes. Only in the last stage of the war were they finally used in aircraft.

In April 1914 Charles Broadwick invented the back pack container, his design resembled a sleeveless coat, the canopy and suspension lines were stowed on the back, the apex was attached to a static line on the back with a breakaway tie and a static line that could be hooked anywhere available, it similar to the design used today.

He demonstrated it to the army just a few months before WW 1, with his adopted daughter Tiny, then twenty years old. She had been jumping since she was fifteen years old.

She jumped from a Curtis biplane and used the risers to steer to a perfect landing. After that jump she was never seen again.

This amazed the General and his staff. The Generals report to the Army was great, but they ignored it, and later American pilots flew into combat without parachutes because the Generals thought they would abandon their planes at the very slightest chance of trouble, hence no parachutes.

During the war only Germans provided parachutes for their pilots, it was a canopy and suspension lines stored in a container. When it came time to depart the aircraft, they lifted the container from under the seat, stood on the seat and tossed the container over the side, then followed it, a little crude but it worked and all the other pilots envied them, especially since they had to ride theirs down in flames.

From the book, Into The Valley, by Col. Charles H. Young:

1918: Isolated French raids in WW I during which two-man demolition teams parachuted behind German lines to destroy communications.

1918, July-October: Small-scale Allied airborne resupply during the Mihiel and Meuse-Argonne campaigns.

Colonel Billy Mitchell attempted to get parachutes for his aviators, without success, but the Army did conduct some tests, and they were still testing when the war ended in 1918. But Colonel Mitchell thought of others ways to use parachutes. To him goes the distinction of suggesting the first Airborne parachute assault forces.

The idea of parachutes for military personnel to employ for 3D maneuver was first suggested by the late Colonel William (Billy) Mitchell, U.S. Army Air Corps during WWI even before they had chutes for American flyers!

His idea was to assign infantrymen to the Air Force and to jump them behind the enemy to cut them off and use the air force to protect them, but his idea was not used.

This is a letter I found in a book written by Colonel Billy Mitchell about his meeting with Gen. Pershing:

"I proposed to him that in the spring of 1919, when I would have a great force of bombardment planes, he should assign one of the infantry divisions permanently to the Air Force, preferably the 1st division; that we would arm the men with a great number of machine guns and train them to go over the front in our large airplanes, which would carry ten or fifteen Soldiers. We could equip each man with a parachute, so when we desired to make a rear attack on the enemy, we could carry these men over the lines and drop them off at a prearranged strong point, fortify it, and we could supply them by aircraft with food and ammunition. Our low flying attack aviation would then cover every road in the vicinity, both day and night, so as to prevent the Germans falling on them before they could thoroughly organize the position. Then we could attack the Germans from the rear, aided by an attack from our Army from the front, and support the maneuver with our great Air Force."

The war ended twenty five days after the meeting. The idea came from the mind of a visionary who wouldn't live to see his ideas come into being. But he was proven right.

Recent reports indicate the ITALIANS actually dropped Paratroopers in WWI! The first use of Paratroops goes back to WWI when Italian officers landed behind Austrian lines for reconnaissance.

Colonel Young continues:

1928: Italian pilots dropped supplies by parachute to the dirigible Italia, stranded at the North Pole.

1929-30: Italian paratroopers made mass jumps in North Africa.

1931: The U.S. Army Air Corps flew a field artillery battery complete with equipment to Panama as a demonstration of "hemispheric defense." Two years later, in keeping with U.S. tacticians' preference for airlanding rather than parachute delivery during this period, the maneuver was repeated in Panama, but with a full battalion. Then, in maneuvers near Fort DuPont, Delaware, AAC Capt. George C. Kenney "astounded his colleagues" by airlanding an infantry detachment behind "enemy" lines.

youtube.com/watch?v=yPv8Bm-aE9o

youtube.com/watch?v=yPv8Bm-aE9o

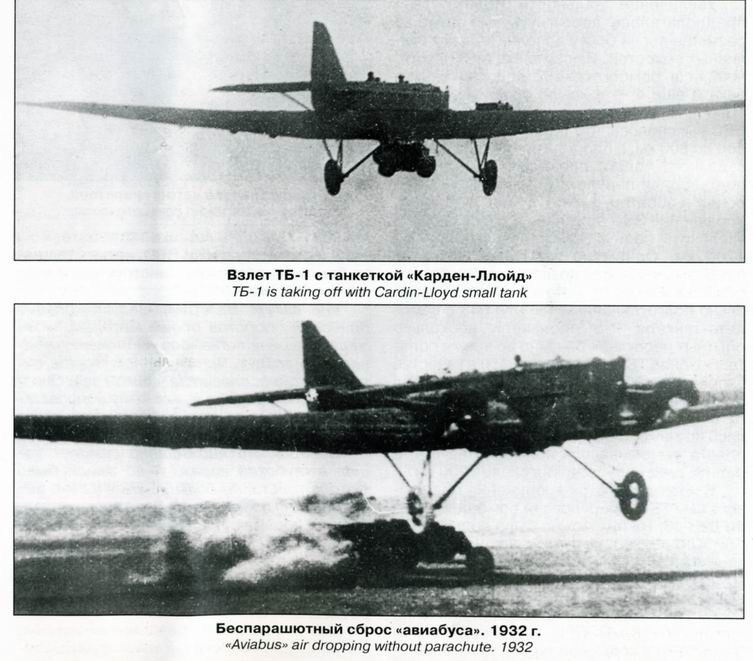

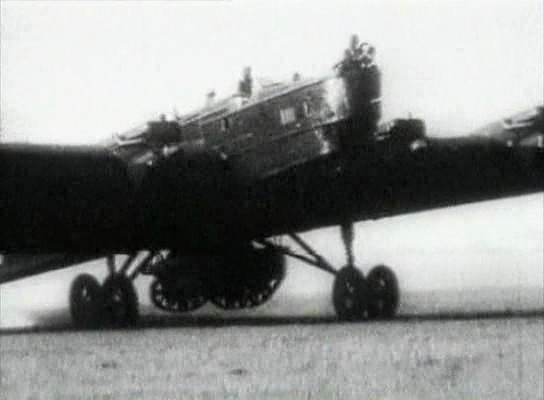

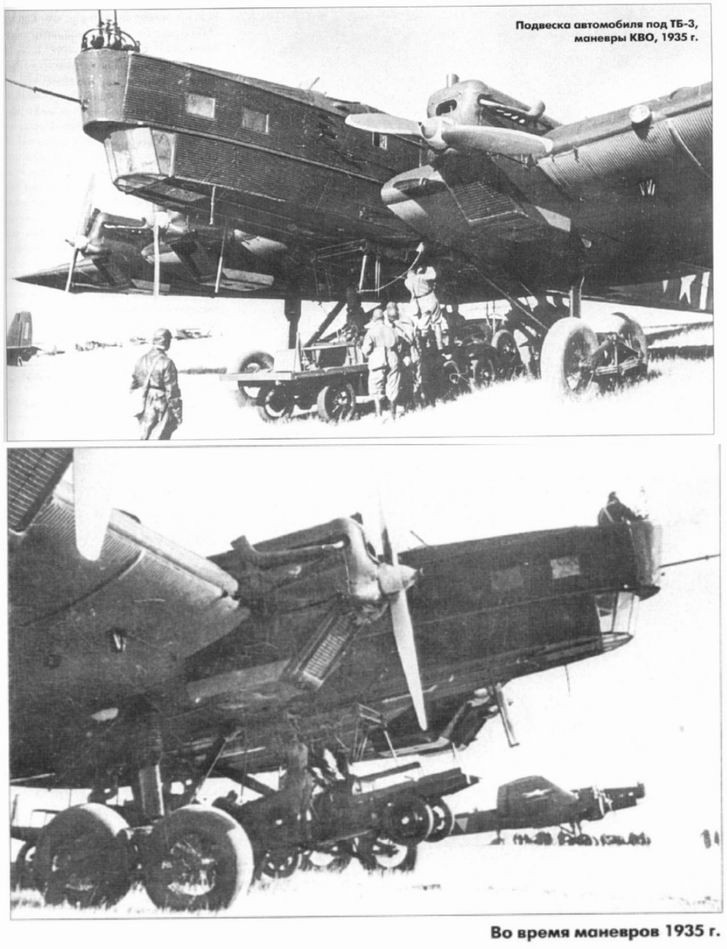

1933, 18 August: Soviet demonstration, Moscow; 46 paratroops jumped from two large bombers, and also dropped a small combat tank by parachute.

1935, 1 March: During Soviet airborne maneuvers at Kiev, two battalions of infantry were dropped; three 18-passenger gliders were also landed on these maneuvers. Gliders had been towed 1,170 miles-in triple-tow. All pilots involved were women.

1936, September-October: Soviet mass drop of 1,200 paratroops at Minsk, while 5,200 paratroops jumped in maneuvers at Moscow.

1938, 7 October: Germans airlanded a complete infantry regiment of 2,800 men in a wheat field near Freiwaldau, Silesia.

The American Army didn't completely abandon development of the parachute, and in 1919 a board was established at McCook Field to determine which type of parachute was suitable for American aviators. The board was headed by Maj. E.L. Huffman, who sent letters to known jumpers in the country to demonstrate equipment and techniques that might be purchased by the government.

One of the respondents was a circus performer known as "Sky High" Irvin, who had been jumping since the age of sixteen and had logged numerous jumps over the years. He presented the first free-fall parachute, a concept that required the jumper to manually release the canopy with a rip cord instead of a static line. The Irvin model used a harness instead of a coat. The canopy was thirty two feet in diameter, with twenty four suspension lines. Instead of being extracted by a static line, the canopy was deployed by a pilot chute that sprang from the container when the jumper pulled the rip cord.

Until this time, it was believed that free falls couldn't be tolerated by human beings, who would either be immobilized by the force of the airflow or by fear of the situation. Irvan proved them wrong by making a delayed-opening jump from 1,500 feet, which convinced the board to sign a contract with him for 300 parachutes. By 1922 a parachute was a required part of the uniform of the military and airmail pilots, and the design remained unchanged for the next fifty years.

The first nation to form a real Paratroop unit was Italy, which makes sense if they had dropped Paratroopers in WWI. The Initial collective drop was made at Cinisello Balsamo, near Milan, on 6 November 1927 from CA-73 troop carriers of the Regfa Aerornautica. The Italians used the Salvator static-line parachute and used no reserve, a policy decision that must have seemed mistaken to the unit's General Gutdoni as he fell to his death a year later, his Salvator streaming above htm m the dreaded "Roman candle" In the late 1930s, the Italians raised complete parachute battalions, and these later expanded into the Folgore and Nembo Divsions, destined to fight with distinction--but never to partake in full-scale Airborne operations during WWII.

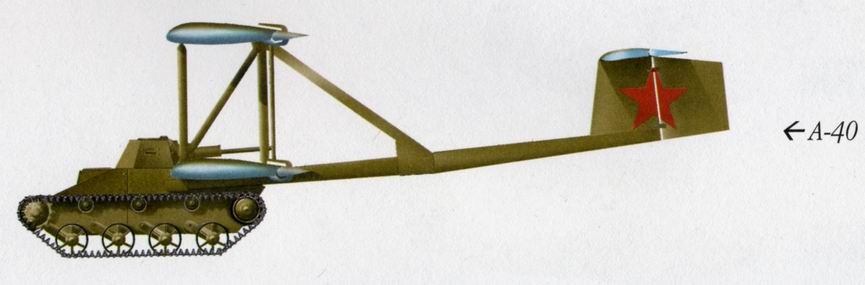

During the 1930s the Russians and Germans started using Airborne troops. The Russians even had bombers and gliders to deliver tanks and "people pods" on the wings of early aircraft to deliver Airborne troops.

The Russians formed Airborne units in 1935 and the Germans in 1937. The French also started in 1937, however the French were defeated before they could use them.

VIDEO: Paratroops in WW2 Europe & North Africa

Paratroopers

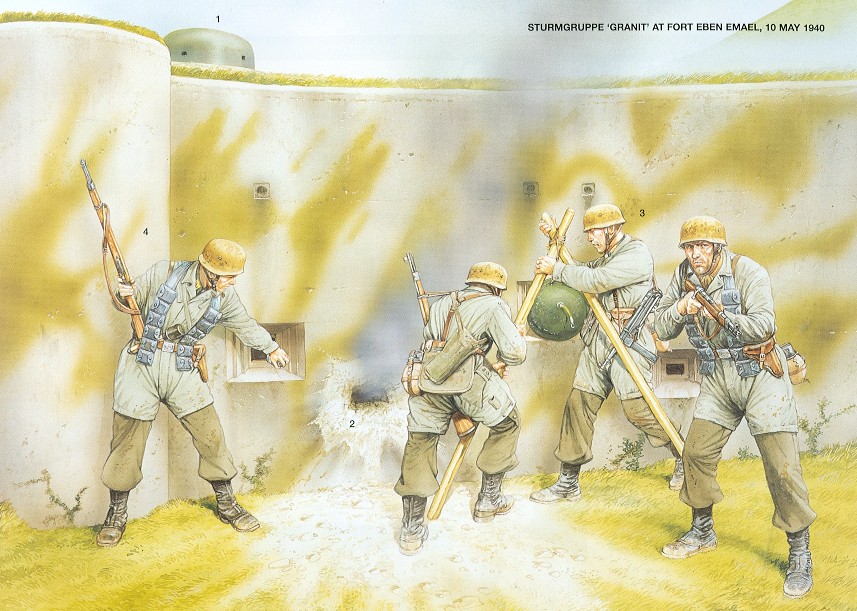

Part 1: German Airborne successes in Norway, Holland, Belgium

youtube.com/watch?v=Rrg4pCZAfu4

youtube.com/watch?v=Rrg4pCZAfu4

Part 2: British Paratroops created by Churchill, Corinth canal attack by German Paras

youtube.com/watch?v=6z_C4Wiypgc

youtube.com/watch?v=6z_C4Wiypgc

Part 3: Germans attack Crete continued, American and British Airbornes drop on North Africa and Sicily

youtube.com/watch?v=3Bl_bVQ5bjk

youtube.com/watch?v=3Bl_bVQ5bjk

Part 4: Russian Airborne used extensively, Italian fighting German Paras bitterly resist allies, American Airborne saves beach head at Salerno

youtube.com/watch?v=oqCd4r1apXk

youtube.com/watch?v=oqCd4r1apXk

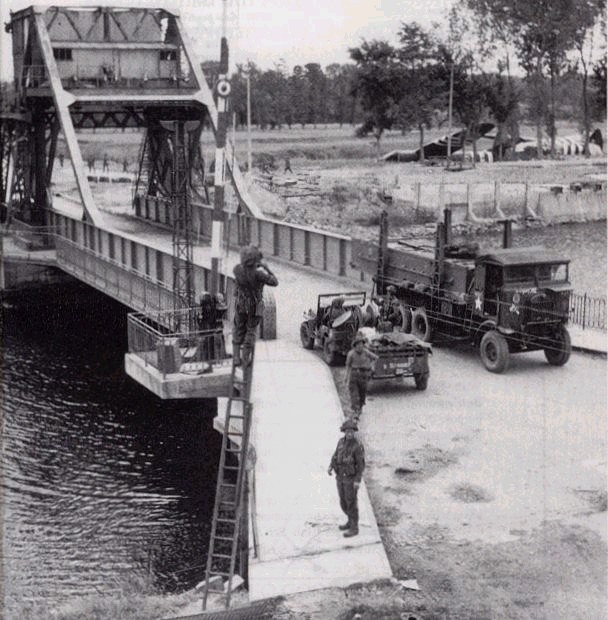

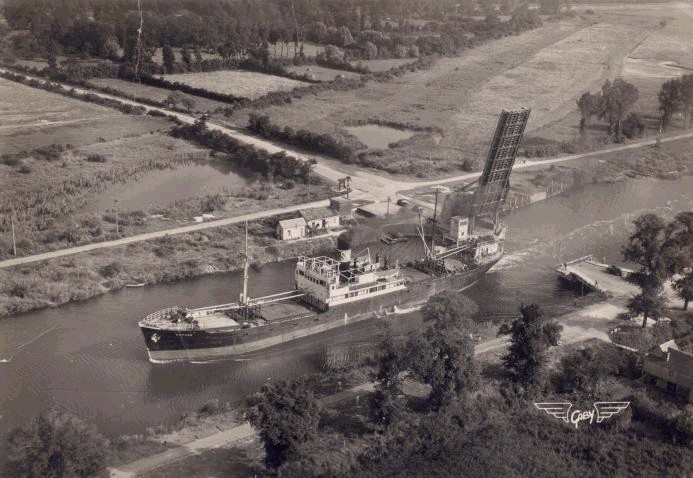

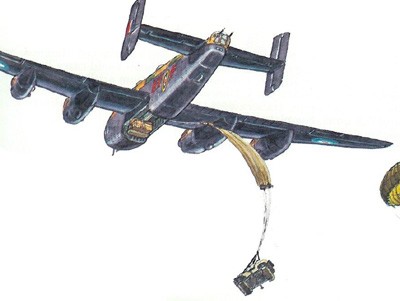

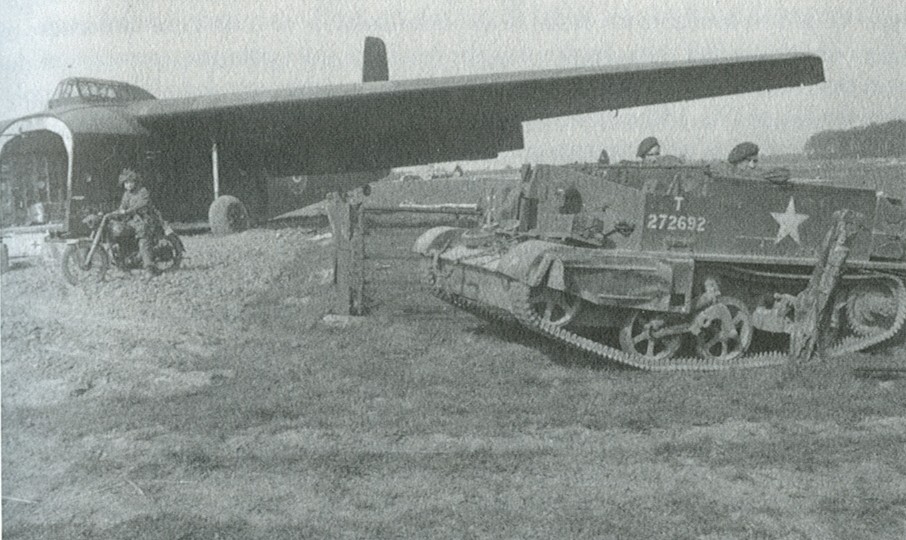

Part 5: Monte Cassino, D-Day, wrongly implies heavy equipment did not arrive when most did by glider including Tetrarch light tanks and Bren gun APCs

youtube.com/watch?v=xxvT0cF0OXk

youtube.com/watch?v=xxvT0cF0OXk

Part 6: Arnhem bridge operation, incorrectly states "armored" jeeps were lost, Battle of the Bulge

youtube.com/watch?v=j7hxl2ur3kY

youtube.com/watch?v=j7hxl2ur3kY

Part 7 Battle of the Bulge, Operation VARSITY

youtube.com/watch?v=PlJ4HztWi_s

youtube.com/watch?v=PlJ4HztWi_s

The success of the German Paratroopers in Holland, Belgium and Crete caused the United States to form an Airborne unit.

The first thing the United States did was to design a chute that could be used for military jumps since most chutes were only used by stunt jumpers.

The "AIR CORPS TEST CENTER" was commission to design and develop a chute for mass military jumps. They designed what was then called the T-4 and was the first chute to have four risers so it could be steered. They also developed the reserve parachute, something only the U.S. Airborne had. No other nation, at that time, used reserves.

German Fallschirmjaeger parachutes were hooked to a single "D" ring and hooked to the harness behind their head. The jumpers were unable to steer them and they landed where ever the wind took them, and contributed to many casualties and battlefield losses.

In April 1940, following the controversies, the War Department approved plans for the formation of a test platoon of Airborne Infantry to form, equip, and train under the direction and control of the Army's Infantry Board. In June, the Commandant of the Infantry School was directed to organize a test platoon of volunteers from Fort Benning's 29th Infantry Regiment. Later that year, the 2nd Infantry Division was directed to conduct the necessary tests to develop reference data and operational procedures for air-transported troops.

In July 1940, the task of organizing the platoon began. First Lieutenant William T. Ryder from the 29th Infantry Regiment volunteered and was designated the test platoon's Platoon Leader and Lieutenant James A. Bassett was designated Assistant Platoon Leader. Based on high standards of health and rugged physical characteristics, forty-eight enlisted men were selected from a pool of 200 volunteers. Quickly thereafter, the platoon moved into tents near Lawson Field, and an abandoned hanger was obtained for use as a training hall and for parachute packing.

Lieutenant Colonel William C. Lee, a staff officer for the Chief of Infantry, was intently interested in the test platoon. He recommended that the men be moved to the Safe Parachute Company at Hightstown, NJ for training on the parachute drop towers used during the New York World's Fair. Eighteen days after organization, the platoon was moved to New Jersey and trained for one week on the 250-foot free towers.

The training was particularly effective. When a drop from the tower was compared to a drop from an airplane, it was found that the added realism was otherwise impossible to duplicate. The drop also proved to the troopers that their parachutes would function safely. The Army was so impressed with the tower drops that two were purchased and erected at Fort Benning on what is now Eubanks Field. Later, two more were added. Three of the original four towers are still in use training Paratroopers at Fort Benning. PLF training was often conducted by the volunteers jumping from PT platforms and from the back of moving 2 1/2 ton trucks to allow the trainees to experience the shock of landing.

Less than forty-five days after organization, the first jump from an aircraft in flight by members of the test platoon was made from a Douglas B-18 over Lawson Field on 16 August, 1940. Before the drop, the test platoon held a lottery to determine who would follow Lieutenant Ryder out of the airplane and Private William N. (Red) King became the first enlisted man to make an official jump as a Paratrooper in the United States Army. On 29 August, at Lawson Field, the platoon made the first platoon mass jump held in the United States.

The first parachute combat unit to be organized was the 501st Parachute Battalion. It was commanded by Major William M. Miley, later a Major General and Commander of the 17th Airborne Division, and the original test platoon members formed the battalion cadre. The Civilian Conservation Corps cleared new jump areas and three new training buildings were erected. Several B-18 and C-39 aircraft were provided for training. The traditional Paratrooper cry "GERONIMO!" was originated in the 501st by Private Aubrey Eberhart to prove to a friend that he had full control of his faculties when he jumped. It was from a western movie they had seen the night before, so on a dare PVT Eberhart yelled the Indian warriors name so all could hear. That cry was adopted by the 501st and has been often used by Paratroopers since then.

The 502nd Parachute Infantry Battalion, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel William C. Lee with men from the 501st as cadre, was activated on 1 July, 1941. The 502nd was far below strength, and 172 prospective troopers from the 9th Infantry Division at Fort Bragg, NC were needed. The response to Lieutenant Colonel Lee's call for volunteers was startling: more than 400 men volunteered, including many noncommissioned officers who were willing to take a reduction in rank ("take a bust") to transfer to the new battalion.

Airborne experimentation of another type was initiated on 10 October, 1941 when the Army's first Glider Infantry battalion was activated. This unit was officially designated as the 88th Glider Infantry Battalion and was commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Elbridge G. Chapman, Jr. Lieutenant Colonel Chapman later became a Major General and commanded the 13th Airborne Division.

As more Airborne units were activated, it became apparent that a centralized training facility should be established. Consequently, the facility was organized at Fort Benning on 15 May, 1942. Since that date, the U.S. Army Parachute School has been known by a variety of names: The Airborne School (1 January, 1946); Airborne Army Aviation Section, The Infantry School (1 November, 1946); Airborne Department, The Infantry School (February, 1955); Airborne-Air Mobility Department (February, 1956); Airborne Department (August 1964); Airborne-Air Mobility Department (October, 1974); Airborne Department (October, 1976); 4th Airborne Training Battalion, The School Brigade (January, 1982); 1st Battalion (Abn), 507TH Parachute Infantry, The School Brigade (October, 1985); and the 1st Battalion (Abn), 507TH Infantry, 11th Infantry Regiment (July, 1991).

The first Airborne Regiment, the 501st was formed in April of 1941 and the first U.S. Army jump school was started at Ft. Benning, GA. The idea for the 250 foot towers came from Coney Island, N.Y. They were built for the 1940 World's Fair, and are still there today. The rest were put together from scratch. With the advent of World War Two, the United States Armed Forces foresaw a need for highly mobile units that the Allies could quickly insert into the theater of battle. An experiment began at Fort Benning, Georgia where a group of volunteers began jumping out of "perfectly good aircraft" while in flight. Thus was born the American Paratroopers. Following great debate and an arduous command decision, the United States Army began forming Airborne units for combat. On 14 March 1941, Company "A", 504th Parachute Battalion was constituted and then activated on 5 October 1941 at Fort Benning, Georgia.

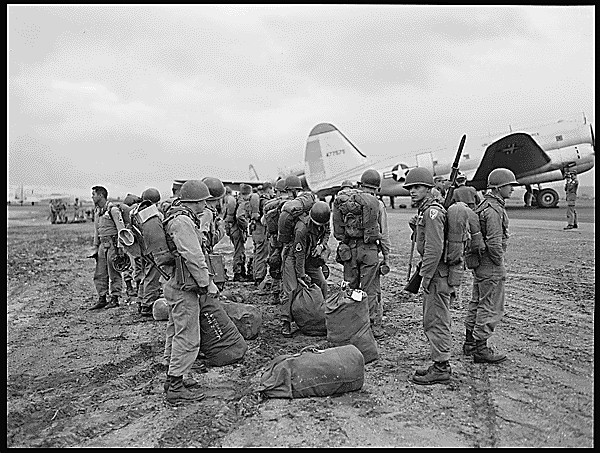

Early Paratroops at the Louisiana Maneuvers

The 504th moved to Fort Bragg, North Carolina for training in February 1942, and became part of one of the Army's first Parachute Infantry Regiments. The 503rd and 504th Parachute Infantry Battalions were joined together to form the 503rd Parachute Infantry Regiment, with the 504th being renamed Company "D", 503rd Parachute Infantry on 24 February 1942.

Although several types of headgear insignia have been worn by parachute and glider organizations since 1942, an insignia peculiar to the Airborne was not authorized until 1949 and did not appear in Army Regulations until 1956. The authorization was first mentioned in AR 670-5 (dated 20 September, 1956), which stated, "Airborne insignia may be worn when prescribed by commander...The insignia consists of a white parachute and glider on blue disk with a red border approximately 2 1/4 inches in diameter overall."

In December, 1943, the all black "555th Parachute Infantry Company (Colored)", later re-designated Company A, 555th Parachute Infantry Battalion (and remembered by many as the "Triple Nickel"), arrived at Fort Benning for Airborne training. This training event marked a significant milestone for black Americans in the combat arms. The first troops in the unit were volunteers from the all-black 92nd Infantry Division stationed at Fort Huachuca, Arizona. After proving their skills, the battalion was not sent overseas, but was deployed to the western United States for "Operation FIREFLY," dropping in to fight forest fires set by Japanese incendiary balloons in the Pacific Northwest. During this mission, the 555th earned the nickname the "Smoke Jumpers." In 1948, after full integration of the Armed Forces was finally effected, black Americans were finally given their full rights as American combat Paratroopers and made their first combat jump while attached to the 187th Regimental Combat Team during the Korean War.

As an independent battalion, the 503rd sailed to Scotland in June 1942, becoming the first American parachute unit to go overseas in World War Two. It was attached to the British 1st Airborne Division for training. The training included mass tactical jumps from C-47 aircraft at 350 feet, extensive night training, and speed marching for 10 miles to and from the training area daily; and on one occasion, 32 miles in 11 hours. On 2 November, as the 503rd was staging for Operation TORCH, the invasion of North Africa, it was reorganized and re-designated as Company "D", 509th Parachute Infantry. On this momentous day, as C-47's flew over the English countryside, the 509th Paratrooper was born.

The first U.S. Army Airborne Divisions were created on August 15 1942. The 82nd and the 101st. Then came the 11th, 13th and 17th Airborne Divisions. The following listing/descriptions takes this history to the present day. An "AIRBORNE" operation defined here as either airdropping with parachutes and/or airlanding from fixed-wing aircraft into "drop zones" or "assault zones".

Worldwide the beret of the Paratroops is bordeaux-red. This goes back to 1944 when a British Paratrooper suffered a head injury through a jumping accident. When he put his olive-green beret onto his head it changed with the colour of his blood into bordeaux-red. It was then decided that the colour should be changed into bordeaux-red because of the fact that Paratroopers have to get along with extreme dangers. Over the years more and more armies in the world copied these berets and so did the Bundeswehr in 1970. The U.S. Army Airborne wears a maroon red beret.

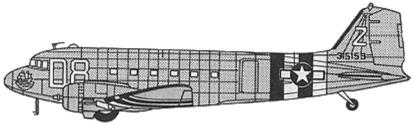

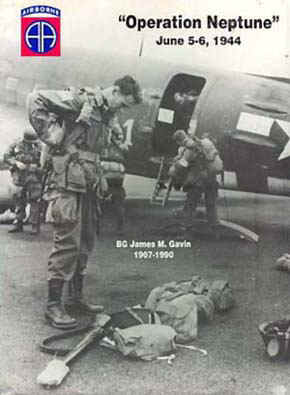

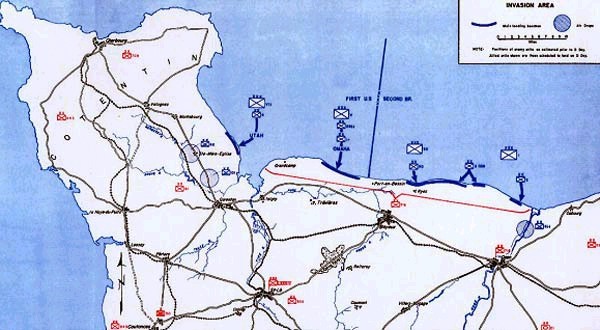

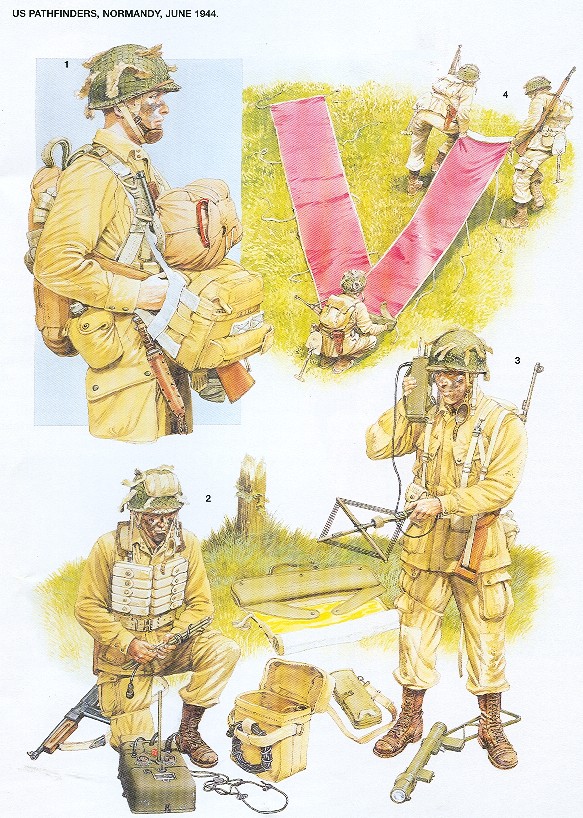

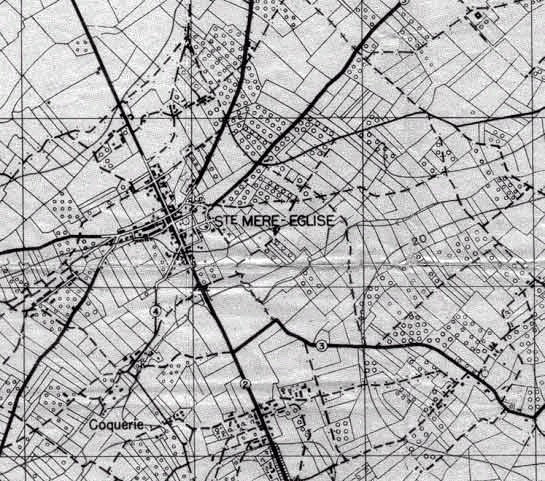

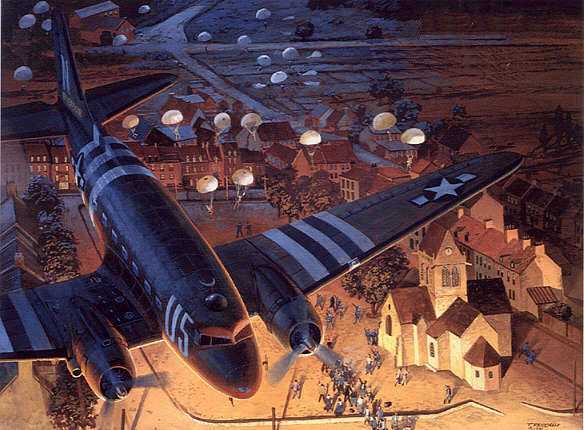

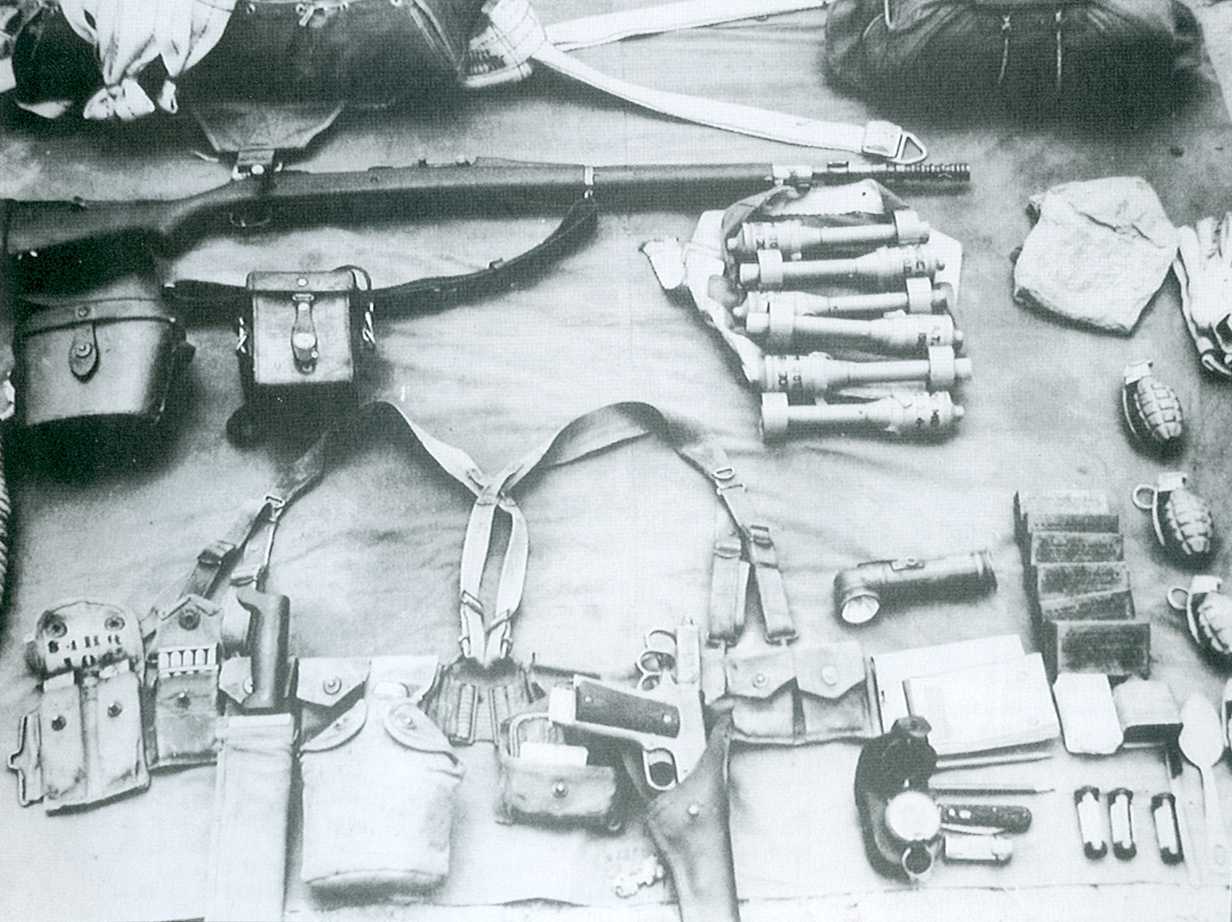

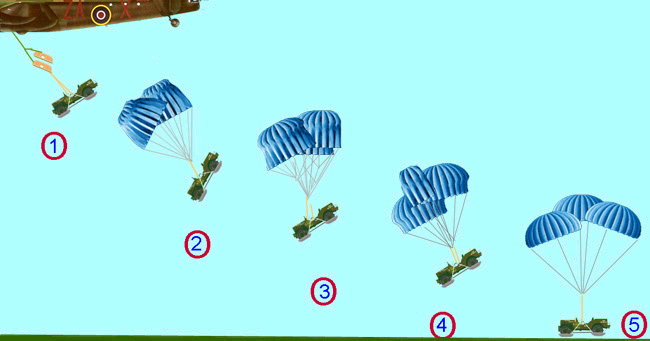

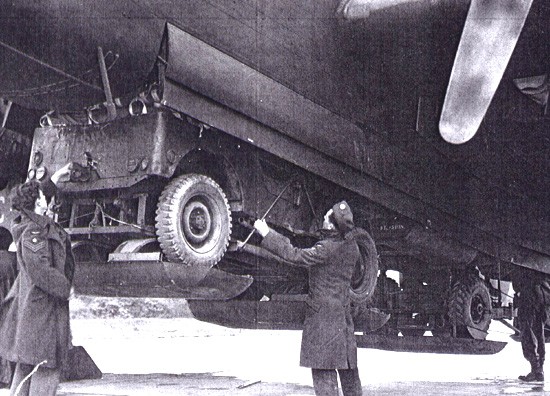

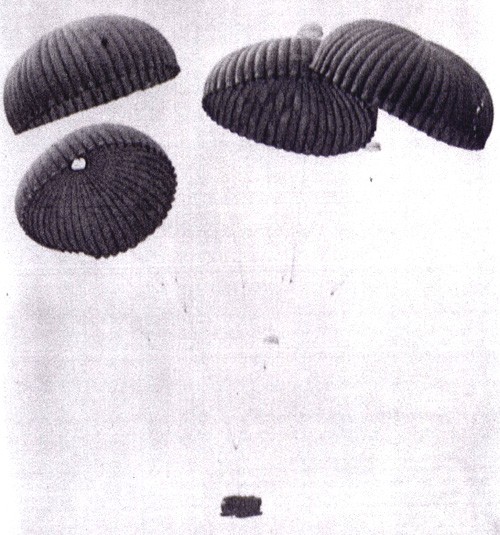

Gavin's paratroopers in WW2 were handicapped by civilian DC-3s that couldn't carry an intact platoon of men and easily caught fire without armor or self-sealing fuel tanks resulting in preventable losses of the 22 it did carry. Unable to carry intact towed guns much less parachute dropping ground vehicles, this forced DC-3s to tow gliders that could carry either a towed gun or a jeep---but not both. This meant open area landing zones had to be secured for the gliders to roll to a stop. Without armament, the DC-3s were vulnerable to enemy fighter planes so Gavin revolutionized airborne operations by night jumps which also protected the planes from anti-aircraft fires. To overcome the confusion of being in the dark, Gavin had his men memorize terrain features and sand table rehearse plans and contingency plans and be self-reliant and able to take the initiative in non-linear battlefield situations not be lemming marines. He created pathfinders to mark drop zones in the dark to improve assembly on top of objectives so they didn't have to walk far. Studying the German's troubles jumping from the very small JU-52 jump door, he exploited the large C-47 jump doors by having every Para jump complete weapons and equipment and minimize separate container drops to just 75mm pack howitzers in pieces--but roped together for fast re-assembly. Because supplies could only be dropped through small fuselage openings or underwing shackles, they were spread out all over and difficult to recover from open areas where the enemy could fire, and paras lacked vehicles with armor protection.

All of these conditions are not true today so there is no excuse why the U.S. Airborne is still handicapped! The current U.S. Airborne is a disgrace to the memory of the Airborne forefathers sitting on laurels bought and paid for by others and accepting self-serving handicaps that don't exist.

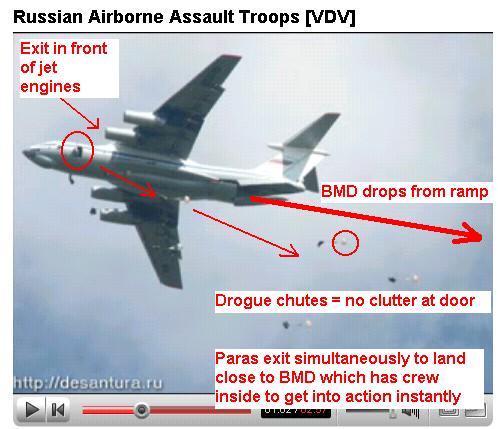

GPS insures that t-tail aircraft not only drop EXACTLY where we intend, but tell paras on ground exactly where they are. No need for rolling open fields for gliders to roll, a single nitrogen inerted fuel tank C-17 t-tail ramp aircraft can drop 80 tons on supplies on pallets, and M113 Gavin light tracked armored fighting vehicles (aka light tanks) can be on these pallets to not only recover the supplies with forklifts but also transport para infantry and anti-tank weapons ready-to-fire on the vehicle not towed---at 60 mph under armor protection. Air refueling enables fighters to escort our t-tail transports but our transport aircraft could and should be armed with their own air-to-air missiles and radar-guided cannon to swat SAMs in self-defense. Delayed opening timer parachutes with small drogue chutes would enable every para to jump if needed from high altitudes around 10, 000 feet above enemy air defense and have his main chute open at low altitude for a normal jump. Furthermore, with M113 Gavins paras need not land on top of heavily defended objectives but can take them by surprise from indirect drop zones. An American Airborne that foot-slogs or rides in road-bound, wheeled trucks when it has the most airlift of any force in human history---more than enough to have hundreds of amphibious, cross-country-mobile light tracked AFVs in use---is a disgrace.

All of the handicaps of the WW2 Airborne are solved, we just need people with 21st century minds in today's Airborne who want to execute 3D maneuver warfare as a Gavin "Sky Cavalry" not sit on their asses and do seize & hold re-enactments pretending they are crippled when its all in their minds.

Furthermore, reading the war diaries of the British light troops surrounded near Arnhem below:

pegasusarchive.org/arnhem/war.htm

Its increasingly clear that 3D maneuver troops must have a "hard shell" in the form of their own light tracked armored fighting vehicles (LTAFVs) so enemy high explosive pounding of them will not attrit them to where they cannot hold a position. These light tracked AFVs should also have back hoes attachments so overhead cover fighting positions and hull-down vehicle positions can be created to bolster the baseline vehicle armor. LTAFV armored mobility also insures airdropped supplies---however they are scattered---can be recovered so even though the 3D force is in a non-linear situation with enemy all around, their fighting strength can be perpetuated indefinitely 'til the heavier 2D forces link up or they themselves implode the enemy resistance by their own maneuver actions.

The other handicap light troops have against heavier enemy troops is that they don't have the supplies to artillery duel with them to keep them from laying down mortar, rocket and artillery pressures upon them since the latter has home field advantage of greater supplies in hand. The air-mechanized light force needs to never be outgunned and LTAFVs enable this because they can self-propel in a ready-to-fire manner tube and rocket/missile artillery that can through clever design keep the enemy's artillery shut down. Also notice how CAS fighter-bombers when overhead silence enemy guns---the AMS force should have its own "hip-pocket" air force of fighter-in-a-box (FINAB) aircraft in ISO container BATTLEBOXes delivered by KIWI pod aircraft right there on the scene operating from their airhead to do CAS as well as interdict enemy fighter-bombers and pesky UAVs from surveilling overhead to help target for the enemy.

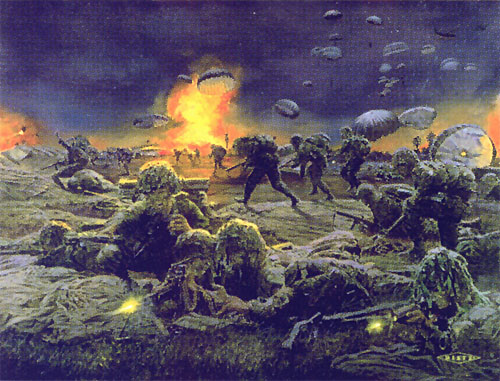

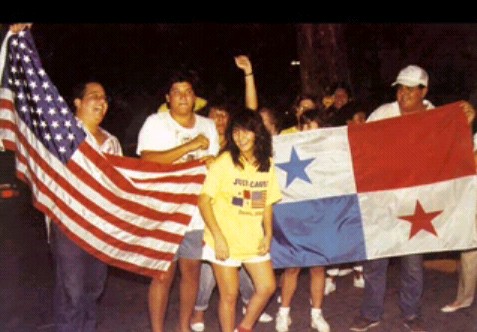

Grenada 1983: Rangers jump under 500 feet to take Point Salines airfield

Date: 8 November 1942

Unit: 509th Parachute Infantry Battalion (PIB)

Operation: Torch

Troopers: 556

Country: Algeria

Dropzone: Tafaraquoi, La Senia

Aircraft: C-47

Type Air delivery: Day Mass low-level tactical personnel static-line jump after long-range deployment from England.

In the first U.S. airborne operation of the war, the 60th Troop Carrier Group of the 51st Wing flew 39 x C-47s non-stop in a night flight from England to points near Oran, carrying the 2nd Battalion of the 503rd Parachute Infantry (soon redesignated the 509th Parachute Infantry Battalion), whose task it was to capture key airfields in advance of the amphibious Allied invasion force. Confusion regarding the intentions of the French forces in the region quickly compounded problems associated with poor planning, failed communications, excessive distances, and inadequate training. Soon, however, a number of small, improvised airborne operations were developed for key points, mostly airfields, across Algeria and eastward in the race for Tunis. These operations were conducted by the 60th, 62rd, and 64th Groups of the 51st Wing, commanded by then-Col. Paul L. Williams. Airborne troopers for these operations included the 509th and the British 1st Parachute Brigade (comprising a total of three battalions), which began arriving in Algeria on 11 November, transported by the 62nd and 64th Groups.

"You Have Your Orders" by Jim Dietz

The training paid off when the 509th spearheaded the Allied invasion of North Africa. The longest Airborne operation in history (so far) occurred 8 November 1942. After a C-47 flight of over 1600 miles from England, the battalion seized Tafarquoi Airport in Oran, Algeria by parachute assault. On the night of Saturday, November 7th, 1942, just eleven months to the day, after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, 556 Paratroopers of the 509th Parachute Infantry Battalion, under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Edson Duncan Raff, took off from England to jump into French Northwest Africa in the initial step to liberate Europe from German occupation. The battalion's mission was to seize two French airfields at Tafaraqoui and LaSenia to deny their use by enemy fighters. Operation Torch, as the amphibious landing in North Africa was codenamed, was an unusually complex military operation. Without any secure bases in the operational area, Allied forces had to deploy from bases in England and travel a great distance to the landing areas. In the Airborne plan of Operation Torch, the 39 x C-47 aircraft of the Paratroop Task Force, commanded by Colonel William C. Bentley, flew 1500 miles over the mountains of Spain, across the western Mediterranean Sea, to arrive badly scattered over the North African coast west of Oran, Algeria, at dawn on November 8th. Nearly out of gas, several aircraft landed in the desert without dropping their Paratroopers, several aircraft were shot down by enemy fighters, several planeloads jumped early and were captured in Spanish Morrocco, while the main force with Lieutenant Colonel Raff also jumped early some 35 miles east of the objective airfields. Although he broke several ribs in a hard landing, Lieutenant Colonel Raff continued to lead his Paratroopers toward their objectives. After a full day and a night forced march, a company of weary Paratroopers reached the airfield at Tafaraoui on the morning of November 9th. Both airfields had already been captured by Allied amphibious forces.

Date: 15 November 1942

Unit: 509th PIB

Operation: Torch

Troopers: 350

Country: Algeria

Dropzone: Youks les Bains

Aircraft: C-47

Type Air delivery: Day Mass low-level tactical personnel static-line jump

One week later, after repacking their own chutes (every man was his own Rigger in those days), the battalion conducted their second combat jump on 15 November 1942 to secure the airfield at Youk-Les-Bains near the Tunisian border. From this base the battalion conducted combined operations with various French forces against the German Afrika Korps in Tunisia. At 9:30 a.m. on November 15, 1942, 350 Paratroopers from the 509th Parachute Infantry Battalion jumped onto the enemy occupied airfield at Youks Les Bains in Algeria for the battalion's second combat mission in just seven days. In spite of the injuries sustained on his earlier jump, Lieutenant Colonel Raff, the 509th Battalion Commander, led this mission as well. The Paratroops landed on a cleared area adjacent to the runway. Within twenty minutes the Paratroops had assembled, secured the airfield, and accepted the surrender of the French Third Zouaves Regiment, which defended the airfield. Lieutenant Colonel Raff ordered his Company "D" to dig in around the airfield and dispatched his Company "E" on foot to secure another airfield at Tebessa, fifteen kilometers away. Soon after the Paratroopers secured the second airfield at Tebessa, again without opposition, a German JU-52 transport attempted to land there but was shot down. After a week, the Paratroopers of the 509th Parachute Infantry were reinforced by an American tank destroyer company and some British engineers. With this added force, Lieutenant Colonel Raff's Paratroopers began conducting sorties across the border into Tunisia to attack German Paratroop and Italian forces around Gafsa. The aggressive actions of the 509th Parachute Infantry Battalion from Tebessa southward to Gafsa succeeded in protecting the Allied flank during the drive eastward towards Tunis. The 3rd Regiment of Zouaves (French Algerian Infantry), awarded their own Regimental Crest as a gesture of respect to the American Paratroopers. This badge was awarded to the battalion commander on 15 November 1942 by the 3rd Zouaves' Regimental Commander, and is worn today by all members of the 509th Infantry.

Date: 24 December 1942--

Unit: 509th PIB, Hdqt's. Co. Two French Paratroopers-

Troopers: 32 -

Country: Tunisia

Dropzone: El Djem

Aircraft: C-47

Type Air delivery: Day, Mass, low-level tactical personnel static-line jump

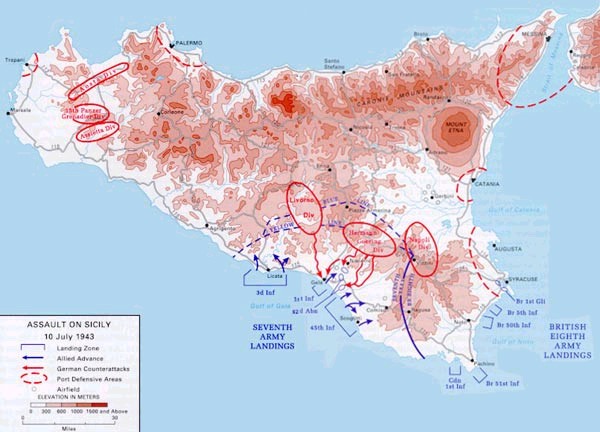

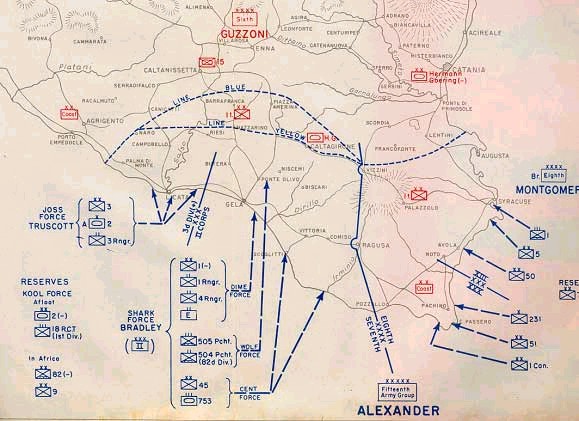

Date: 9 July 1943

Unit: 504th Parachute Infantry Regiment 3rd Battalion (Jumped first); 505th Regimental Combat Team (RCT), Includes: 505th PIR, 456th PFA & Co. B, 307th Engr.

Operation: Husky I

Troopers: 3,406

Country: Italy

Dropzone: Gela, Sicily

Aircraft: C-47

Type Air delivery: Night Mass low-level tactical personnel static-line jump, wing shackle bundle drops, Gliders

Date: 10 July 1943

Unit: 504th Regimental Combat Team (RCT), Includes: 504th PIR, 1st & 2nd Btn.; 376th PFA & Co.A, 307th Engr.

Operation: Husky II

Troopers: 2,304

Country: Italy

Dropzone: Gela, Sicily

Aircraft: C-47

Type Air delivery: Night Mass low-level tactical personnel static-line jump, wing shackle bundle drops, Gliders

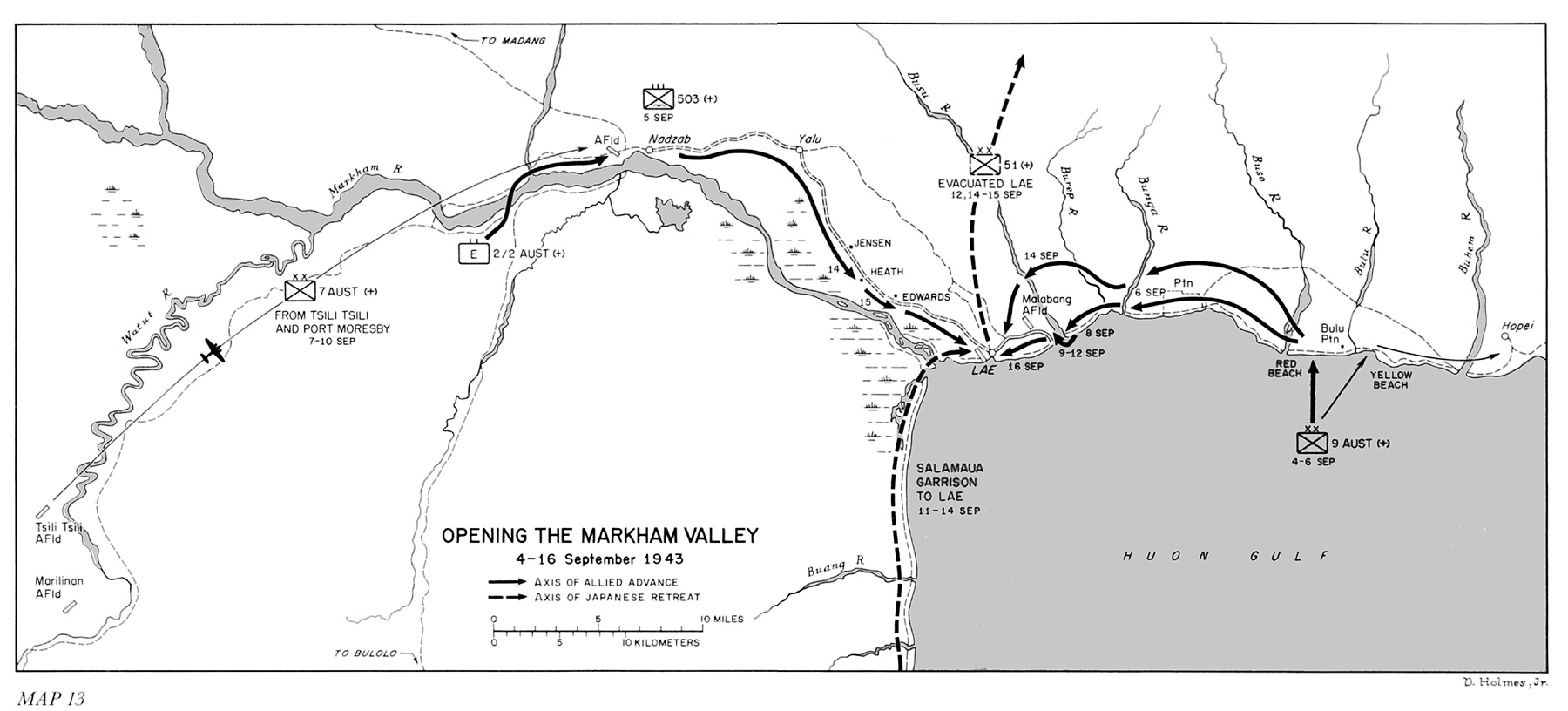

Date: 5 September 1943

Unit: 503th PIR and 2/4th Australian Infantry Force

Troopers: 1,700

Country: New Guinea

Dropzone: Nadzab, Markham Valley

Aircraft: C-47, A-20s (smokescreens)

Type Air delivery: Day Mass low-level tactical personnel static-line jump, wing shackle bundle drops

youtube.com/watch?v=wuz0TpzqwWY

youtube.com/watch?v=wuz0TpzqwWY

First American airborne operation in the Pacific took place at Nadzab, New Guinea. The American 503rd PIR dropped from 85 x C-47s of the 374th and 375th Troop Carrier Groups, 54th TC Wing, in a mission to secure the airfield at Nadzab and prepare it for airlanding the Australian 7th Division, which was to then push toward Lae from the west and link up with Allied amphibious invasion forces moving in from the east. The same aircraft that carried in the 503rd and some Australian artillerymen who were hastily trained as parachutists, also airlifted 420 planeloads of infantry Soldiers by 11 September. The paradrop, which took place in daylight as General MacArthur circled above in a B-17 observation bomber, was well coordinated, accurate, and effective. Along with several key Troop Carrier maneuvers in the States during the summer and late fall, strong support by General Ridgway, and in conjunction with the soon-to-follow emergency missions at the Salerno beachhead, this mission contributed to a renewed commitment to Airborne-Troop carrier by American military leaders.

1st R.A.R's lineal history goes back to the 65th Battalion, 2nd Australian Imperial Forces (A.I.F.), engaged in the fight against the Japanese. That unit was a part of the Australian 7th Division A.I.F. In 1943 a U.S. unit was to jump on a Japanese fortified area in New Guinea, elements of the 7th Australian Division, A.I.F were hastily chosen to jump with them in the form of and Australian Artillery Section of 2 x 25 Pounders, from the ranks of the 7th Australian Division, A.I.F. came a Section of 2/4th Artillery Battery under command of Lt Pearson. The 33 men in the Section had two days hasty Parachute Training prior to the big day, at which time 2 of the originals were injured and ruled out. They were replaced on the day by two that had not jumped at all. On the Big Day, 5 September 1943, The U.S. 503rd Parachute Infantry Regiment (P.I.R) went through the door over NADZAB in New Guinea, the 2/4th Artillery Section went out the door with them. The jump master considered they were not trained well enough and thus made them jump without side arms. Their side arms/small arms went out the door in a pannier, after hitting the Landing Zone, they had one of their guns up and firing within 2 hours of the jump. Those gunners of the 7th Australian Division, A.I.F., didn't know then that they were setting the pace for another Australian Unit to join with the 503rd, some 22 years later on another foreign airstrip when 1st R.A.R. whose lineal history goes back to the 7th Australian Division, A.I.F., were to join with the Sons of the 503rd P.I.R. at Bien Hoa, Vietnam.

Airlift historian and Vietnam C-130 combat veteran, Sam McGowan writes:

"...the Airborne assault on Nadzab, an airstrip in the Markham Valley in Papau New Guinea in the fall of 1943. If there is a single World War II battle that deserves to be studied by modern advocates of Airborne and Airland operations, Nadzab is it.The attack on Nadzab was planned and executed by the air staff of the Fifth Air Force, the air element of the Southwestern Pacific Command of General Douglas MacArthur. Lt. Gen. George C. Kenney, the Fifth Air Force commander, conceived the attack as a means of catching the Japanese forces at Lae in a pinch between Airborne and Airlifted troops attacking from the northwest and infantry attacking up along the Huon Peninsula (sometimes called the Lae Peninsula) from the southeast. Nadzab was the fruition of a plan Kenney conceived in early 1943 after American and Australian troops, many of whom had been airlifted across the Owen Stanley Mountains, defeated the Japanese force at Buna, a village southeast of Lae. Kenney conceived an Airborne attack at a time when he had no Airborne forces at his disposal. During a visit to the United States in the spring of 1943 Kenney requested the assignment of an Airborne Division to his command. Instead of a Division he got a Regiment, the 503rd Parachute Infantry (the 11th Airborne Division arrived in the Pacific in time for the invasion of the Philippines.)

During the interim prior to the arrival of the first American Paratroops in the Southwest Pacific, Kenney ordered the construction of a secret advanced airfield on the north slopes of the Owen Stanleys less than a hundred miles south of Lae. The new field, at a village known as Tsili-Tsili (and pronounced Silly-Silly) was constructed entirely by airlift. Engineers and construction materials were flown into an existing strip at Marlinan, about four miles from the new site. (The Marlinan strip was not suitable for use by fighters, but it was suitable for C-47s.) Originally the engineers planned to use jeeps and trailers to transport materials between the two bases, until someone came up with the idea of sawing Army trucks in half and transporting the halves in C-47s, then reassembling them in the field. It was not until the base was ready for fighters that it was detected by the Japanese. An attack caught a formation of C-47s as they were approaching to land. At least one transport was shot-down before U.S. fighters broke up the attack.

The Nadzab attack was planned as a two-fold operation. American Paratroops airlifted from Port Moresby would jump onto an existing, but lightly defended, airstrip and secure the field while the C-47s returned to Marlinan to pick up/airland Australian infantry who had been prepositioned there by airlift in anticipation of the operation.

On the morning of the attack the drop formation of some 90 x C-47s from the 374th, 317th and 375th Troop Carrier Groups took off from Seven Mile Aerodrome at Port Moresby and assembled over the field. While the C-47s were assembling into drop formation, then heading out for the drop zone at Nadzab three groups of powerfully armed B-25 strafers were taking off from other airfields in the area. Though factory produced versions of the B-25 gunships would later serve in the Pacific, the airplanes at Nadzab were mostly conventional B-25 medium bombers that had been converted in the field into forward-firing gunships. The bombardier's position was removed from the airplane and the nose was filled with a battery of eight .50-caliber machineguns while additional guns were installed in pods mounted on the sides and bottom of the bombers, giving each B-25 a battery of 12-14 .50-caliber Heavy Machine Guns firing forward along the longitudional axis of the airplane. In addition to the machineguns, each B-25 carried a bomb-bay full of small parachute-fragmentation bombs, bombs that floated to earth beneath parachutes to detonate right above the ground, spraying fragments in every direction.

Minutes before the C-47s arrived over the Nadzab drop zone, a very large force (as many as 90 ships) of B-25 gunships hit the airfield. After strafing the drop zone, the B-25s dropped their loads of parafrag bombs. As the last B-25 left the field a flight of A-20s came over and dispensed a cloud of smoke around the DZ to conceal the troopers from the enemy postions in the trees. Above the airstrip a flight of three VIP-carrying B-17s observed the operation. General Kenney was in one airplane, General Douglas MacArthur (who was erroneously referred to by some of his men as "Dougout Dug") was in another. A fighter cover of P-38s and P-39s kept the Japanese fighters at bay.

The Paratroopers landed under the concealment of the smoke without taking a single casualty from enemy fire. Within minutes after they were on the ground, the Japanese on the airfield surrendered with very little resistance. The Paratroops hurriedly secured the airfield perimeter and prepared the airstrip for the arrival of troop carrying C-47s that began arriving in the afternoon. As the C-47s arrived, the Australian infantry assembled and, along with the American Paratroops, began attacking toward Lae.

Now that, folks, is how an Airborne operation is supposed to work, as conceived by General Billy Mitchell and further developed in the minds of men like Kenney, who had served as an observer in Europe in 1940. The Airborne attack was swift and sure, and it followed behind a massive aerial attack by heavily armed fixed-wing gunships who literally swept the area with heavy machinegun fire. The Allies had previously achieved aerial superiority, the gunships suppressed the fire of the Japanese troops who were in the vicinity of the previously determined-to-be lightly defended area and the troops jumped onto a DZ where they met little resistance.

I might also add that the operation was planned and executed, not by a massive staff in Washington, at Fort Bragg and at Scott or Eglin, but by a commander and staff in the field who knew the area and the military situation, and who tailored their operation for the conditions. In fact, the whole thing was carried out by a single command that included heavy bombers, medium bombers, fighters and transports as well as Airborne forces and infantry. And it worked.

The U.S. Army Paratroopers of the 1/503rd PIR roar over the smoke in C-47s and jump in at an incredibly low 250 feet! The airfield is taken over quickly with light casualties as the Kenney/MacArthur, Air/Ground team began their amazing run of spectacular victories against the Japanese without the thousands of friendly casualties the frontalist approach used by the Navy/mc in the North Pacific received.

ibiblio.org/hyperwar/USA/USA-P-Rabaul/USA-P-Rabaul-11.html

Nadzab: The Airborne InvasionThe Jump

Capture of Nadzab had been spectacularly effected on 5 September. This mission, assigned to Col. Kenneth H. Kinsler's 503rd Parachute Infantry Regiment, was coupled with the additional mission of preparing the airstrip for C-47's carrying Maj. Gen. George A. Vasey's 7th Australian Division from Marilinan and Port Moresby.[17]

www.youtube.com/watch?v=5zo4PTMg9uA

Reveille for the men of the 503rd sounded early at Port Moresby on the morning of 5 September. The weather promised to be fair, although bad flying weather over the Owen Stanleys delayed take off until 0825. New Guinea Force had prepared its plans flexibly so that the seaborne invasion on 4 September would not be slowed or altered if any threat of bad weather on 5 September delayed the parachute jump, but Kenney's weathermen had forecast accurately.

The paratroopers and a detachment of

--207--

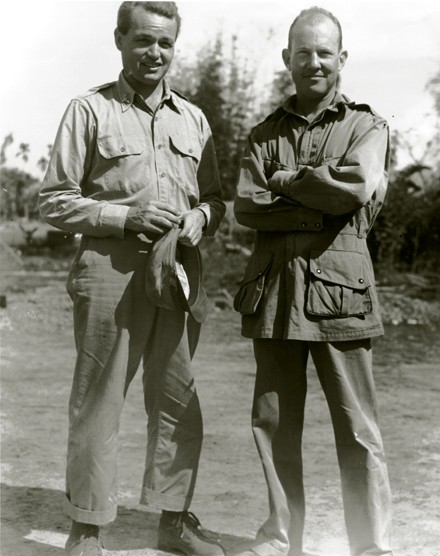

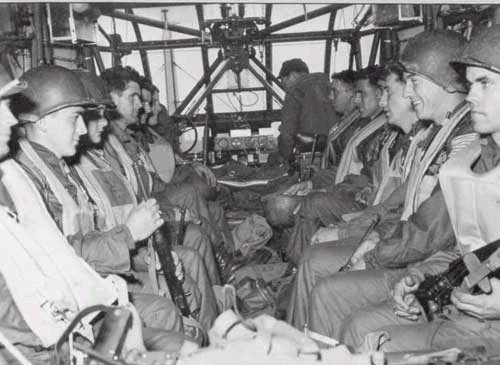

C-47 TRANSPORT PLANES LOADED WITH PARACHUTE TROOPS for the drop at Nadzab. Two men at left are General Kenney and General MacArthur.

2/4th Australian Field Regiment which was to jump with its 25-pounder guns reached the airfield two hours before take off. [18] There they put on parachutes and equipment. The 54th Troop Carrier Wing had ninety-six C-47's ready, and the troops boarded these fifteen minutes before take-off time.

The first C-47 roared down the runway at 0825; by 0840 all transports were aloft. They crossed the Owen Stanleys, then organized into three battalion flights abreast, with each flight in six-plane elements in step-up right echelon.

An hour later bombers, fighters, and weather planes joined the formation over Marilinan, on time to the minute. All together 302 aircraft from eight different fields were involved. The air armada then flew down the Watut Valley, swung to the right over the Markham River, and headed for Nadzab. The C-47's dropped from 3,000 feet to 400-500 feet. The parachutists had stood in their planes and checked their equipment over Marilinan, and twelve minutes later they formed by the plane doors ready to jump.

In the lead six squadrons of B-25 strafers with eight .50-caliber machine guns in their noses and six parachute fragmentation bombs in their bays worked over the Nadzab field. Six A-20's laid smoke after the last bomb had exploded. Then came the C-47's, closely covered by fighters.

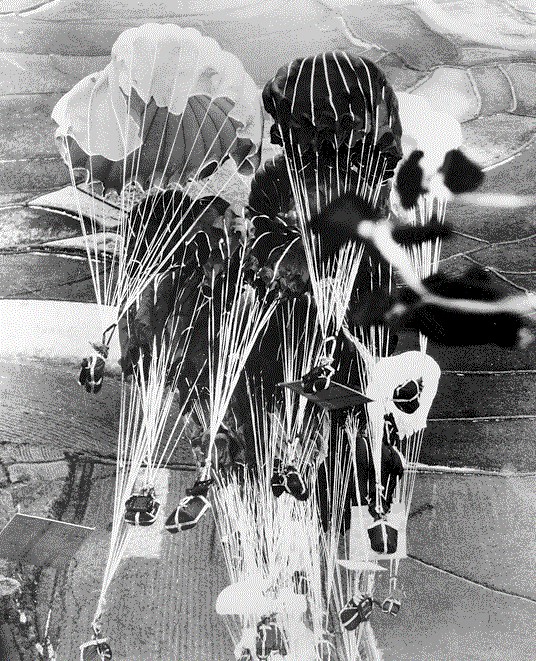

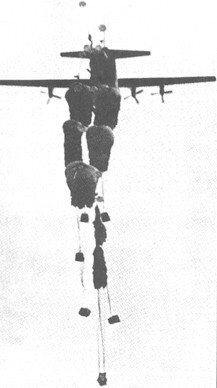

The paratroopers began jumping from the three columns of C-47's onto separate jump areas about 1020. Eighty-one C-47's carrying the 503rd were emptied

--208--

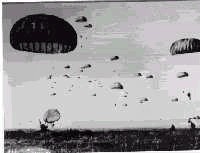

AIRDROP AT NADZAB, MORNING OF 5 SEPTEMBER 1943. The paratroopers began jumping from C-47's onto separate jump areas about 1020.

in four and one-half minutes. All men of the 503rd but one, who fainted while getting ready, left the planes. Two men were killed instantly when their chutes failed to open, and a third landed in a tree, fell sixty feet to the ground, and died. Thirty-three men were injured. There was no opposition from the enemy, either on the ground or in the air. Once they reached the ground, the 503rd battalions laboriously moved through high kunai grass from landing grounds to assembly areas.

Five B-17's carrying supply parachutes stayed over Nadzab all day. They dropped a total of fifteen tons of supplies on ground panel signals laid by the 503rd. The Australian artillerymen and their guns parachuted down in the afternoon. The whole splendid sight was witnessed by Generals MacArthur and Kenney from what Kenney called a "brass-hat" flight of three B-17's high above. MacArthur was in one, Kenney in another, and the third B-17 was there to provide added fire power in case the Japanese turned up.

The 503rd's 1st Battalion seized the Nadzab airstrip and began to prepare it to receive C-47's. The 2nd and 3rd Battalions blocked the approaches from the north and east. As soon as the parachutists had begun landing, the Australian units that had come down the Watut River--the 2/2d Pioneer Battalion, the 2/6th Field Company, and one company of the Papuan Infantry Battalion--began landing on the north bank of the Markham. They made contact with the 503d in late afternoon and worked through the night in preparing the airstrip.

--209--

The next morning the first C-47 arrived. It brought in advance elements of the U.S. 871st Airborne Engineer Battalion.

Twenty-four hours later C-47's brought in General Vasey's 7th Division headquarters and part of the 25th Australian Infantry Brigade Group from Marilinan, where they had staged from Port Moresby. Thereafter the transports flew the Australian infantry and the American engineers directly from Port Moresby. By 10 September the well-timed, smoothly run operation had proceeded fast enough that 7th Division troops at Nadzab were able to relieve the 503rd of its defensive missions. Enough American engineers had arrived to take over construction of new airstrips.

The 503rd's only contact with the enemy came in mid-September when the 3rd Battalion ran into a Japanese column at Yalu, east of Nadzab. The parachute regiment was withdrawn on 17 September. It had lost 3 men killed jumping, 8 men killed by enemy action, 33 injured jumping, 12 wounded by the enemy, and 26 sick.[19]

This was, comparatively, small cost for the seizure of a major airbase with a parachute jump. Nadzab paid rich dividends. Within two weeks the engineers had completed two parallel airstrips six thousand feet long and had started six others.

The Advance Against Lae

The 25th Australian Infantry Brigade Group moved eastward out of Nadzab toward Lae on 10 September while General Wootten's 9th Division troops were forcing a crossing over the Busu River east of Lae. The Markham Valley narrows near Lae, with the Atzera Range on the northeast and the wide river on the southwest. A prewar road in the Atzera foothills connected Nadzab with Lae, and a rough trail on the other side of the Atzeras paralleled this road from Lae to Yalu, where it intersected the road. Thus while some troops blocked the trail at Yalu, and the 2/33rd Australian Infantry Battalion guarded the line of communications, the 2/25th Australian Infantry Battalion advanced down the road and part of the 2/2nd Australian Pioneer Battalion moved down the north bank of the river.

When a small group of Japanese offered resistance to the advance at Jensen's Plantation, toward the lower end of the valley, the 2/25th Battalion drove it back and on 14 September captured Heath's Plantation farther on. The 2/33rd Australian Infantry Battalion then took over and pushed on toward Lae. By now the Australians had come within range of Japanese 75-mm. guns and found the going harder. But an assault the next day cleared Edward's Plantation and enemy resistance ended.

The advance elements of the 25th Brigade entered Lae from the west the next morning, 16 September. In the afternoon the 24th Brigade, which had advanced from the east and captured Malahang Airdrome on 15 September, pushed into Lae and made contact with the 25th Brigade. Lae had fallen easily and speedily. The Japanese had vanished.

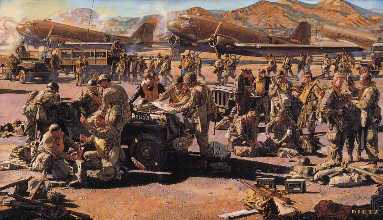

"Eight hours to Glory" by legendary artist Jim Dietz shows the 505th PIR getting ready for the Salerno jump

Date: 13 September 1943

Unit: 504th Regimental Combat Team (RCT) Includes: 504th PIR, 376th PFA & Co. "A" 307th Eng.

Operation: Avalanche

Troopers: 1,300

Country: Italy

Dropzone: Paestum, Salerno

Aircraft: C-47

Type Air delivery: Night Mass low-level tactical personnel static-line jump

Date: 14 September 1943

Unit: 505th Regimental Combat Team (RCT). Includes: 505th PIR, 456th PFA & Co.B 370th Engr.

Operation: Avalanche

Troopers: 2,105

Country: Italy

Dropzone: Salerno, Paestum

Aircraft: C-47

Type Air delivery: Night Mass low-level tactical personnel static-line jump

Salerno was one of the bloodier, more critical operations of the Second World War. For a time the action hung in the balance as strong enemy counterattacks smashed and threatened the very existence of the initial beachhead. This was the opening struggle of the long and bitter Italian campaign.

The Fifth Army held the beachhead at Salerno for four days but were danger of losing it to advancing German assaults and needed assistance quick. The only choice was to utilize the 504th Parachute Infantry Regiment, which had been performing mock assaults, in an effort to provide relief to the dwindling forces of the Fifth Army.

On September 13, 1943 1st and 2nd Battalions were alerted that they would be performing a parachute assault. "Another dry run", was the cynical comment of most men. Nevertheless, each man gave his equipment a last minute check - just in case. Early chow was eaten and immediately afterward the troops fell in at their bivouac areas in the appointed plane loading formations; then marched to the battered and roofless hangars where they picked up their chutes.

The first troopers to board planes were the Pathfinders of the 504th who would be establishing and mark the drop zone which was located in the middle of the Fifth Army. These men devised a plan to mark the drop zone with a flaming "T" using sand and gasoline.

While the Pathfinders were on their way to the fight, the rest of 1st and 2nd Battalion were hard at work. Officers were checking maps and information to decipher the best course of action to help save the Fifth Army and save the beachhead. Noncommissioned officers had Soldiers hard at work issuing parachutes, performing maintenance checks on weapons, and starting to load planes. None of these paratroopers knew the location of this jump or what type of fighting was expected. It was not until the men were seated in the planes that the mission was disclosed. In probably the quickest briefing of any comparable operation of the war, men of the 504th were informed that the Fifth Army beachhead in Italy was in grave danger of being breached and that the 504th was to jump behind friendly lines in the vicinity of the threatened breakthrough in order to stem the German advance.

Under the cover of darkness the planes left for the beachhead. Flying in a column formation they passed over the clearly marked DZ and unloaded their much needed support. With the exception of eight planes which failed to navigate properly to the DZ, but whose planeloads were subsequently accounted for, there was little difficulty or confusion experienced in completing the operation. The regiment assembled quickly and moved to the sounds of cannon and small arms fire within the hour. Later checks revealed that, amazingly, only 75 men had suffered injuries as a result of the jump. In exactly eight hours the 504th had been notified of its mission, briefed, loaded into planes, jumped on its assigned drop zone, and committed against the enemy.

By dawn the regiment was firmly emplaced in a defensive sector three miles from Paestum and Southwest of Albanella. The days of the 14th and 15th of September were spent in anticipation of a tank attack that threatened from the Calore River region to the North. The 2nd Battalion assisted in the repulsing of one tank attack across the Sele River while E Company, on a reconnaissance in force of the same area, encountered scattered and small elements of the enemy. The regimental recon platoon patrolled the area several miles to the front and battalions also sent out reconnaissance and combat patrols of their own with particular emphasis on the Altavilla sector. Hostile artillery fire was spasmodic and largely interdictory in character. Air activity was confined principally to friendly craft, though the enemy in groups of two and three would occasionally make an appearance over 504th positions only to be driven off by intense fire from supporting anti-aircraft units. On the morning of the 16th, the regiment marched four miles to occupy the town of Albanella, where at noon, Colonel Tucker issued to the battalion commanders the order to seize and hold the high ground surmounting Altavilla. The area in the region of Altavilla for several years had been a firing range for a German artillery school; consequently there was no problem of range, deflection, or prepared concentrations that the enemy had not solved long before the advent of the Americans. Needless to say, hostile artillery and mortar fire was extremely accurate and capable of pinpointing with lethal concentrations such vital features as wells, trails, and draws. During the three days that the 504th occupied the several hills behind Altavilla, approximately 30 paratroopers died, 150 were wounded, and one man was missing in action.

The days that followed were, in the words of General Mark Clark, Commander of the 5th Army, "responsible for saving the Salerno beachhead." They included repelling tank attacks and small enemy forces. As the 504th took the high ground at Altavilla, the enemy counterattacked, and on the night of the 17th, it became evident that help had to be secured if the 504th, now completely cut off from friendly forces, was to hold these key positions so necessary for the security of the beachhead. The Commander of 6th Corps, General Dawley, suggested the unit withdraw. Epitomizing the determined spirit of the Regiment, Colonel Tucker vehemently replied, "Retreat, Hell! -- Send me my other battalion!" The 3rd Battalion then rejoined the 504th, the enemy was repulsed, and the Salerno beachhead was saved. This, the first contact with the enemy for men of the 504th since Sicily and the first time that the regiment had been committed as a unit in any single tactical operation, was a battle that turned the tide of the German onslaught on the Salerno beachhead and frustrated their attempts to contain the Fifth Army within the confines of the coastal plain reaching as far as Altavilla. On 1 October 1943, the 504th became the first infantry unit to enter Naples and 3rd Battalion became the first U.S. parachute unit to receive a Presidential Unit Citation as a result of the fierce fighting.

The 504th fought hard in all battles they encountered in Italy. Nothing reflected this more than a diary entry of a German officer found at Anzio. The passage read:

American parachutists...devils in baggy pants...are less than 100 meters from my outpost line. I can't sleep at night; they pop up from nowhere and we never know when or how they will strike next. Seems like the black-hearted devils are everywhere...To this day the paratroopers of the 504th PIR are still known as "The Devils".

Date: 14 September 1943

Unit: 509th PIB

Operation: Avalanche

Troopers: 640

Country: Italy

Dropzone: Avellino

Aircraft: C-47s

Type Air delivery: Night Mass low-level tactical personnel static-line jump

While the 82nd Airborne Division dropped inside American lines to reinforce the Salerno beachhead, the 509th was assigned the mission of cutting enemy supply lines behind the German defensive positions. The 509th launched its third parachute assault at Avellino, Italy, only to find that the valley DZ was occupied the night before by the 6th German Armored panzer Division. The 509th operated independently for some two weeks behind German lines in company and platoon size elements disrupting the German rear area. Separate units scrounged for food and water among the Italian civilians until the unit finally reassembled in Salerno on 28 September 1943. Total casualties were 123 killed or captured including the 509th commander and his entire staff.

Date: March 5-May 17 1944

Unit: Chindits and 1st USAAF Air Commandos

Operation: Thursday

Troopers: 15, 000 men

Country: Burma

Landing Zones: "Broadway" and "Pacadilly"

Aircraft: C-47s, Waco gliders

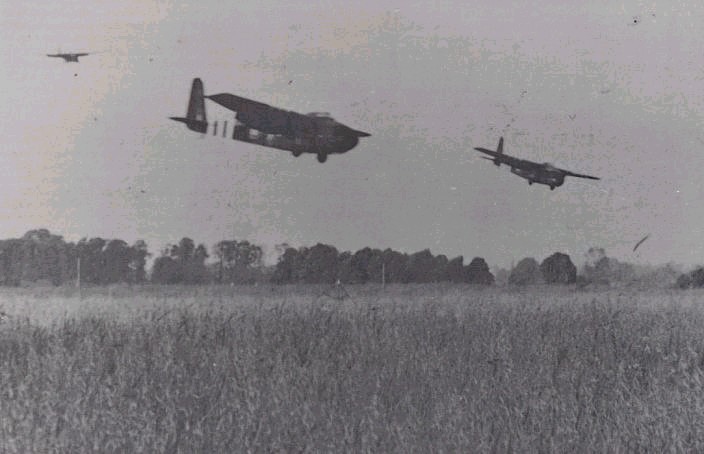

Type Air delivery: Night Daylight glider assaults and resupply landings with mini-bulldozers to clear landing strips for C-47s to airland troops, pack mules, pack howitzers

1944, 5 March-17 May: American glider missions into Japanese-held Burma; first use of double-tow in combat. At the Quebec Conference of August 1943, British Major General Orde Wingate was assigned the task of assisting U.S. General Joseph W. Stilwell's two Chinese divisions in opening up the supply route from India through northern Burma into China. Since the spring of 1942, airsupply from the Assam valley of India over the high, rugged, and remote Himalayas had offered the only viable means of supplying forces in the region around Kunming, China. For these purposes, the Air Transport Command, in conjunction with assigned troop carrier and combat cargo outfits and British RAF transport units, delivered tons of vital supplies through extreme conditions-including attacks by Japanese fighter aircraft-over "the Hump."

1944, 5 March-17 May: American glider missions into Japanese-held Burma; first use of double-tow in combat. At the Quebec Conference of August 1943, British Major General Orde Wingate was assigned the task of assisting U.S. General Joseph W. Stilwell's two Chinese divisions in opening up the supply route from India through northern Burma into China. Since the spring of 1942, airsupply from the Assam valley of India over the high, rugged, and remote Himalayas had offered the only viable means of supplying forces in the region around Kunming, China. For these purposes, the Air Transport Command, in conjunction with assigned troop carrier and combat cargo outfits and British RAF transport units, delivered tons of vital supplies through extreme conditions-including attacks by Japanese fighter aircraft-over "the Hump."

Legendary British Major General Orde Wingate

In preparation for Wingate's Burma operations, to begin in early 1944, a special AAF unit which came to be known as the 1st Air Commando Group was formed lead by Colonel Phil Cochrane...

Colonel Phil Cochrane and a Paratrooper

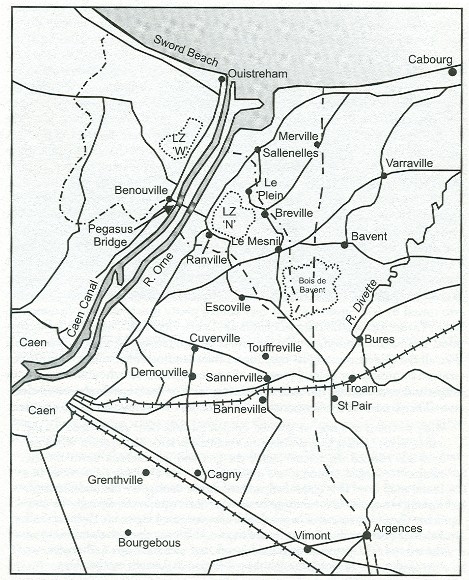

and went into training for purposes of flying Wingate's troops into battle, evacuating the wounded, providing airsupply and direct air support.