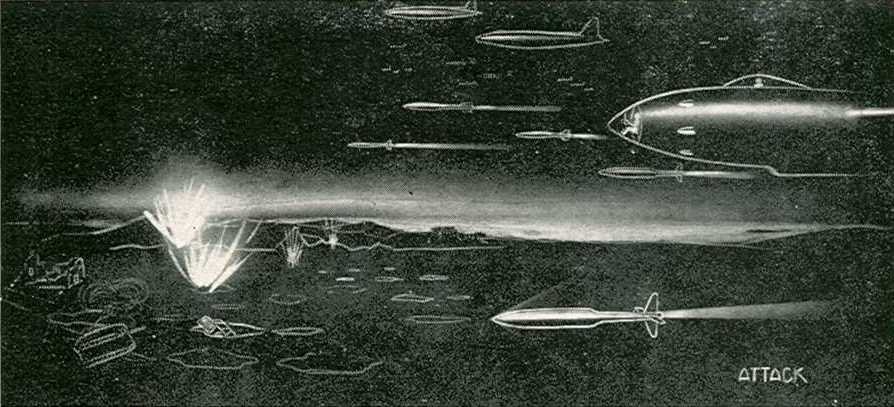

"It was 2,200 yeas later when sea power reached its full potential. Then, in the battle of Normandy, the Allied powers, using hundreds of seacraft of all types, invaded the Continent of Europe. The sea was used to its fullest. It is significant, however, that part of the invading forces were transported by AIR. It was significant because that battle saw sea power at its peak. AIR power was just beginning. And this is the critical point that we have arrived at, and this is the competition we are in. This media that envelops us we must use. We must imagine, design, and develop the means and methods of using it. We must--if our people and our institutions are to survive. For the people with their institutions who best learn how to use this media will survive in this highly competitive world.AIR power is now the decisive element in modern war. And by AIR power is meant every contribution to waging war that man has created and that can be flown. Men, weapons, ammunition, food, bombs, missiles, and all that it will take to fight a future war must FLY. Clearly, therefore, in the development of our AIR power and Airborne potential changes must be made in our ground force equipment as well as in our Air Force equipment.

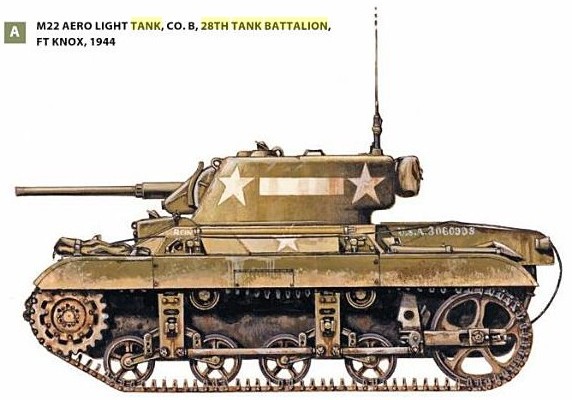

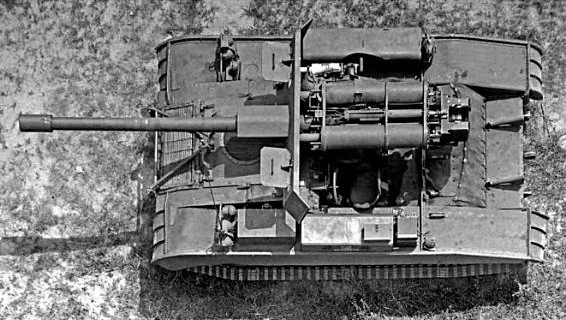

...The conventional type steel and cast iron earth-bound tank cannot in its present form win the battle with air-transported shaped-charge weapons. In its present form it is as exctinct as the elephants of Zama and the heavily armed knights of Agincourt. The entire Airborne-armored problem must be viewed in the light of the capabilities of modern shaped-charge [RPGs] and rocket weapons. The same is true of our communications equipment, tracks, reconnaissance vehicles, artillery, food, and in fact, everything must be flown.

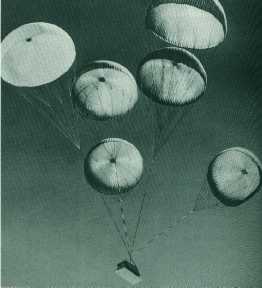

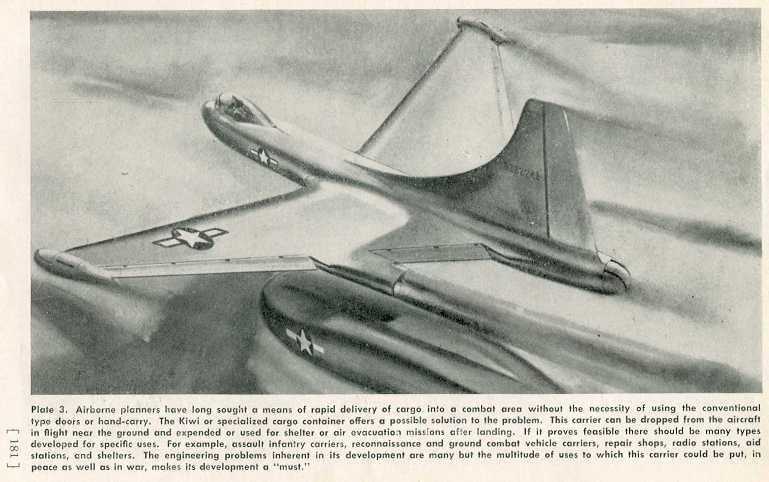

Organizations created to fight the last war better are not going to win the next. Nor is building an airplane around the ground weapons that won the last war an assurance that we will win the next. Keeping foremost in our minds the functional purposes of our means of ground combat, these means must be developed and produced so that they can be delivered to the battlefield in sufficient quantity to gain the decision. Not only must our airplanes, 'chutes, ..be developed but our ground fighting weapons and equipment as well. Only thus, will we attain a position of dominance in Airborne Warfare.

The nation that in the future has the best trained and equipped Airborne Forces has the best chance of survival. Indeed, more than this, only by having such security forces can any nation survive. For as long as these means of waging modern war are available to us, they are available to aggressor nations. And modern Airborne Forces of aggressor nations cannot be fought successfully with the weapons that fought past wars. Not if they are to be engaged at parity and beaten.

Airborne troops are our best national security and the world's most promising hope for international security.

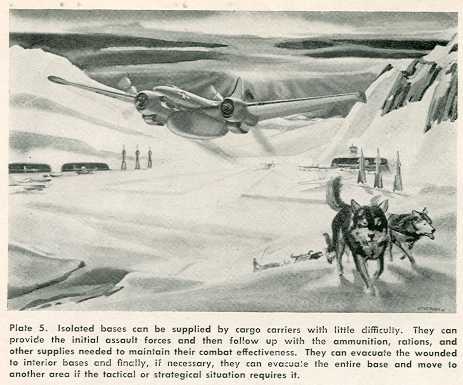

The knowledge of the existence of a well trained Airborne Army, capable of moving anywhere on the globe on short notice, available to an international security body such as the United Nations, is our best guarantee of lasting peace. And the nation or nations that control the AIR control the peace."

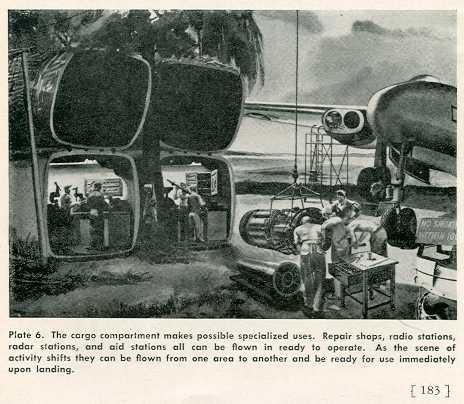

1st Tactical Studies Group OBSERVATIONS to Gavin's book are in DARK RED

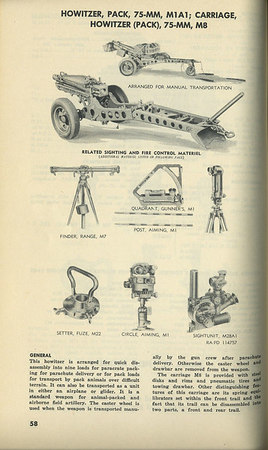

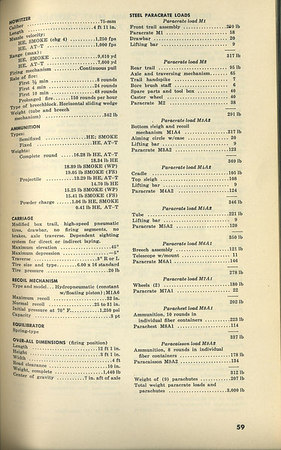

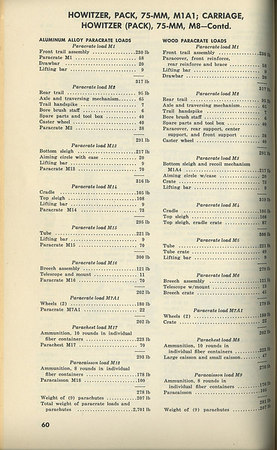

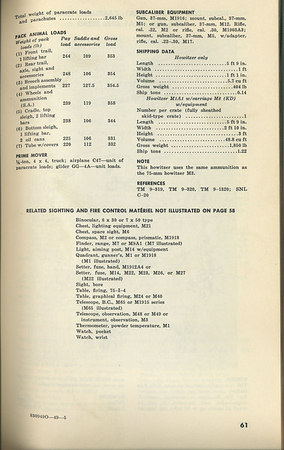

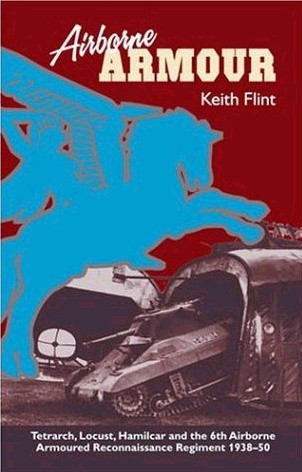

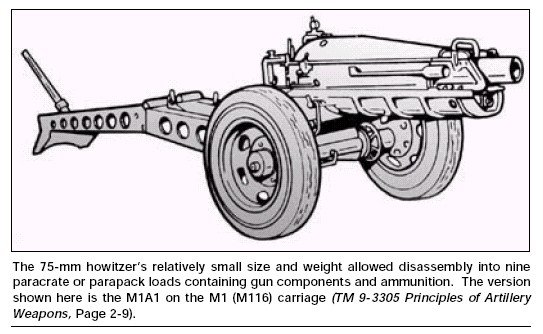

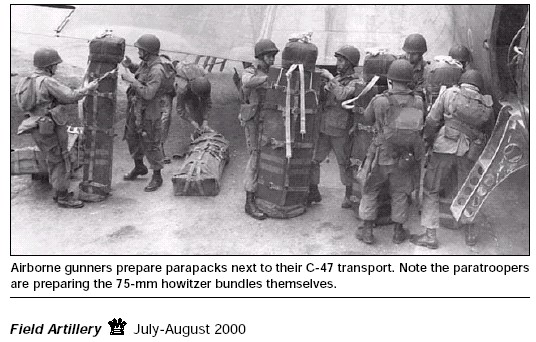

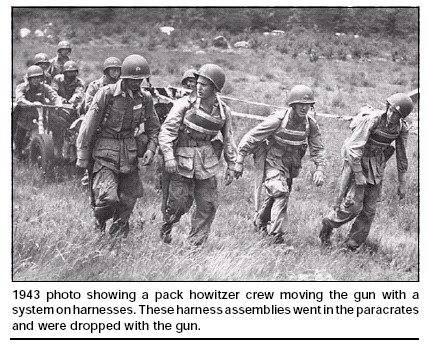

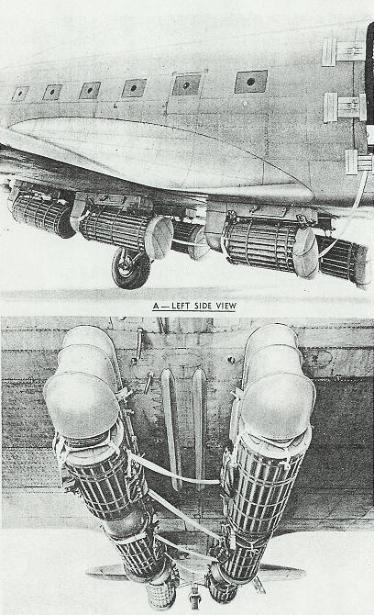

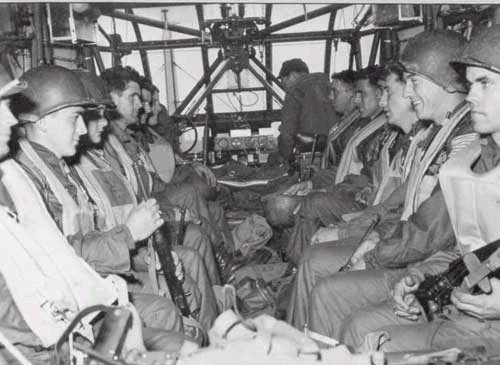

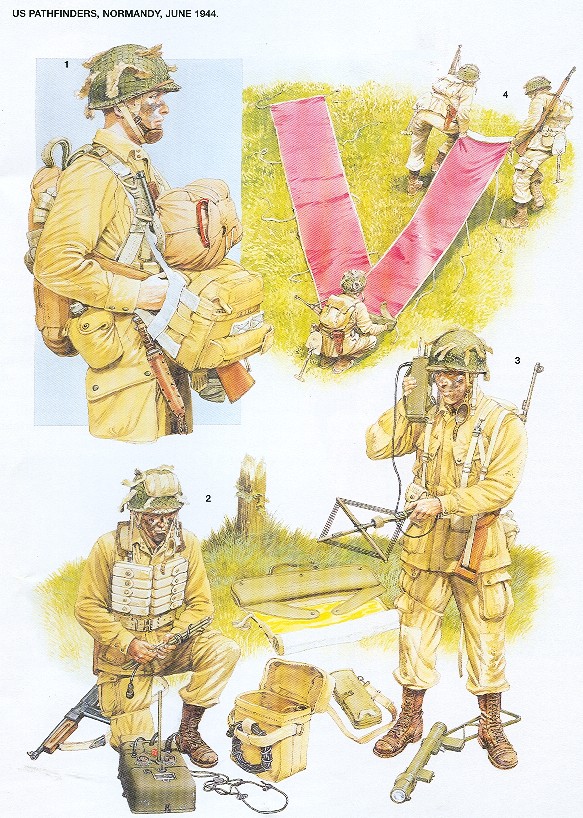

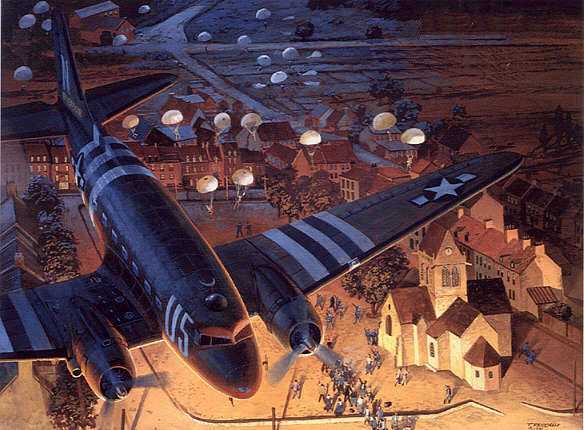

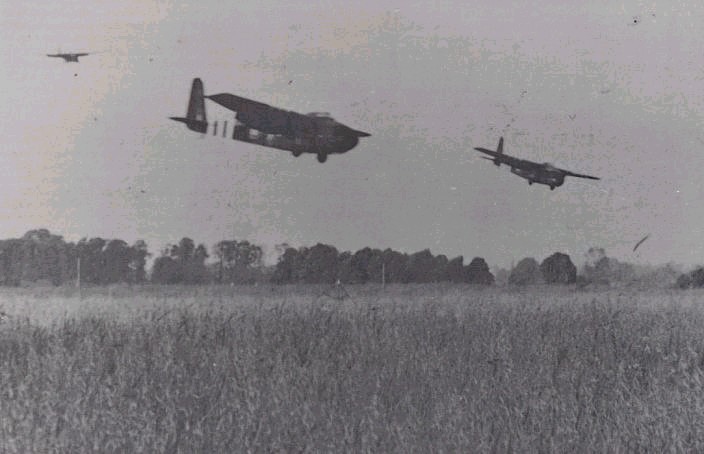

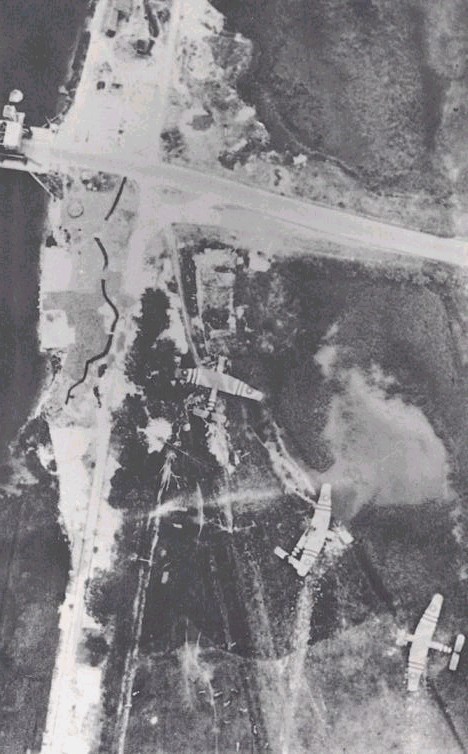

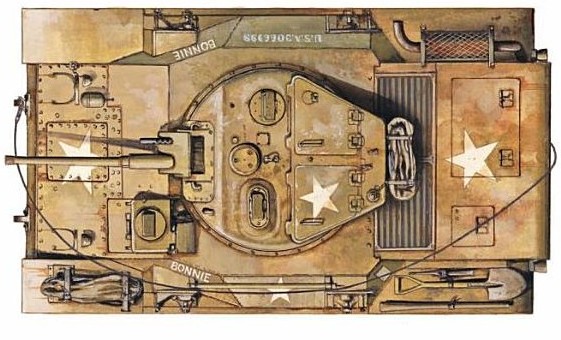

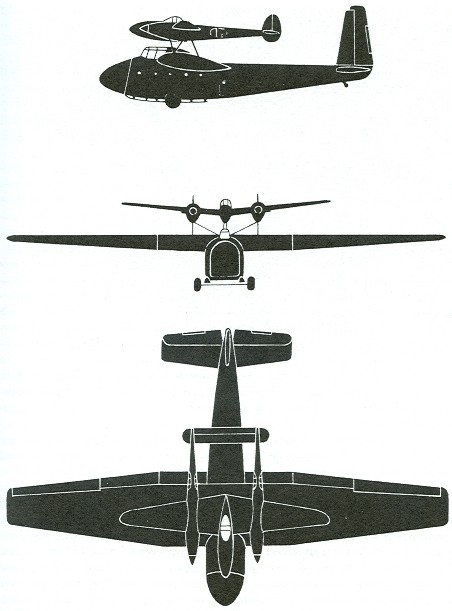

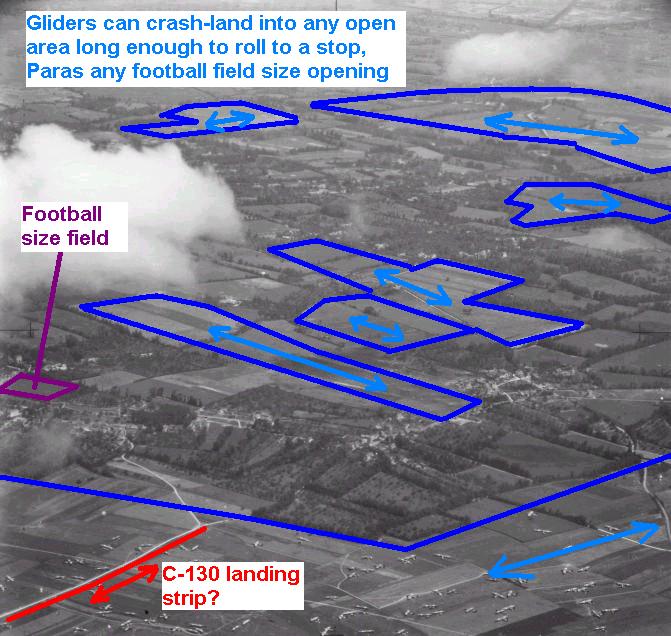

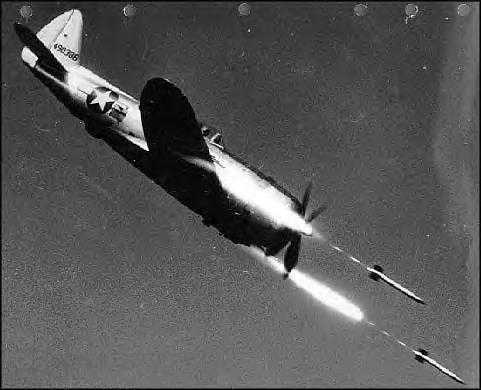

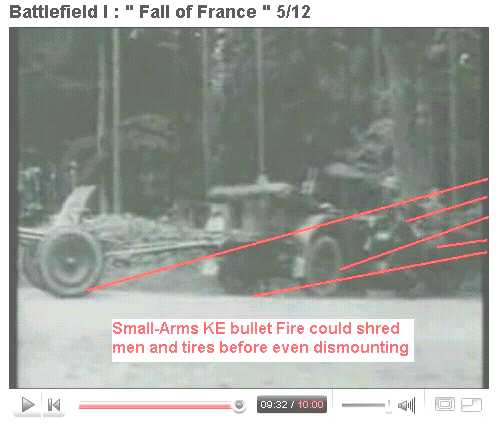

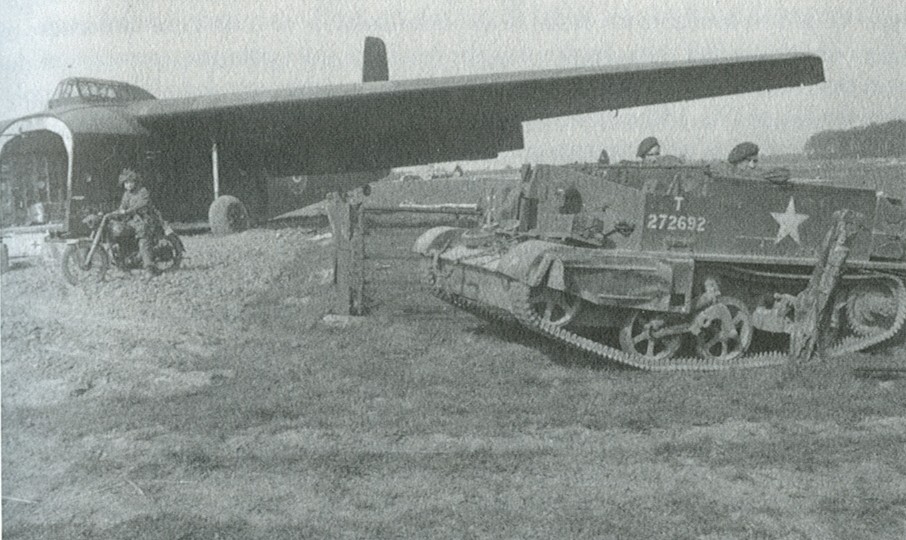

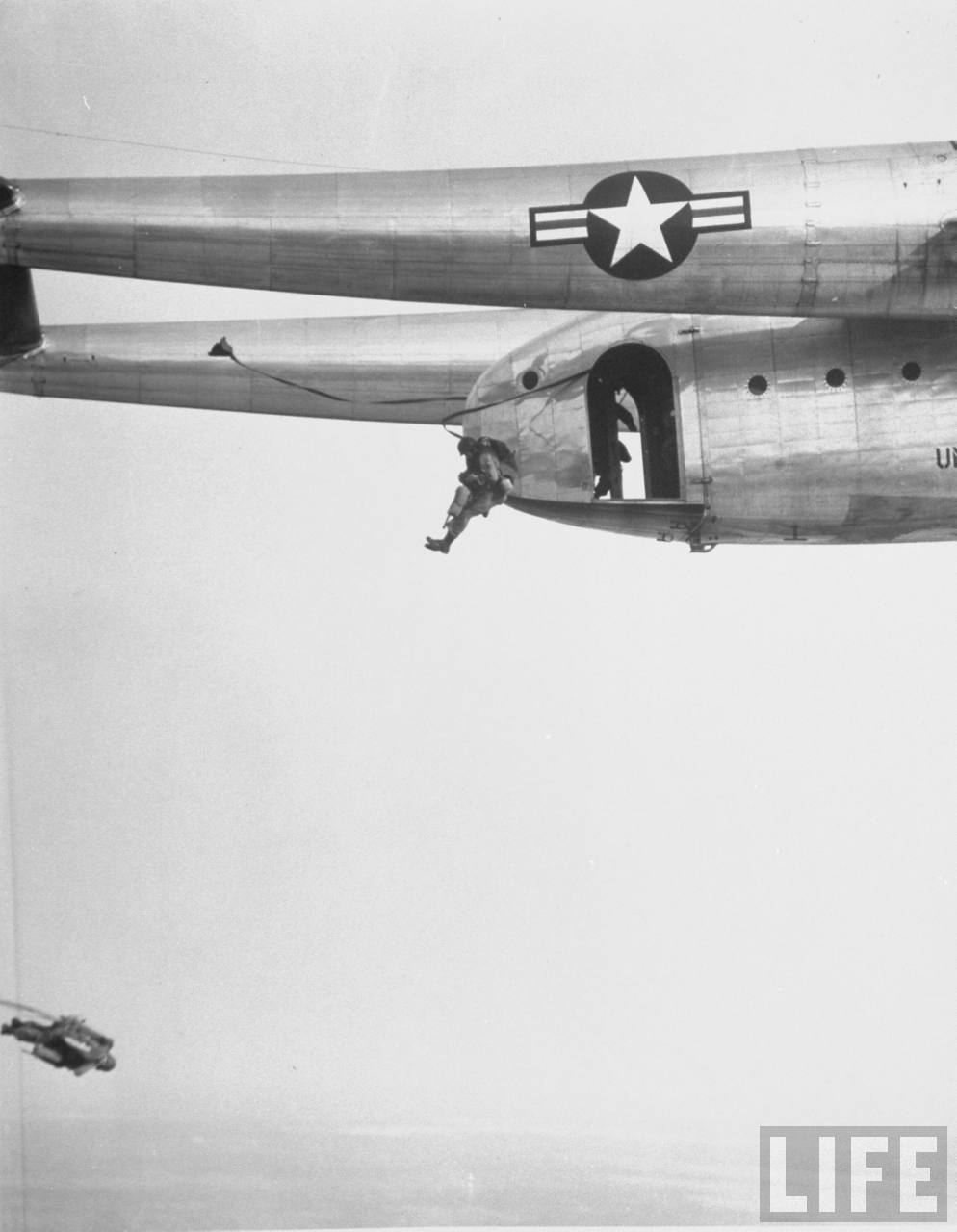

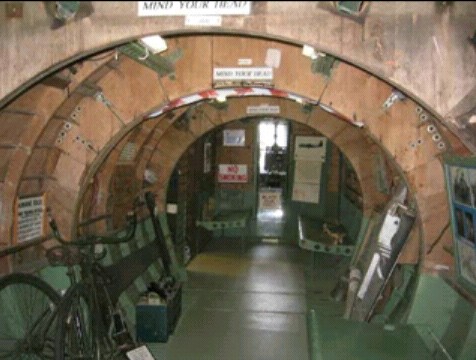

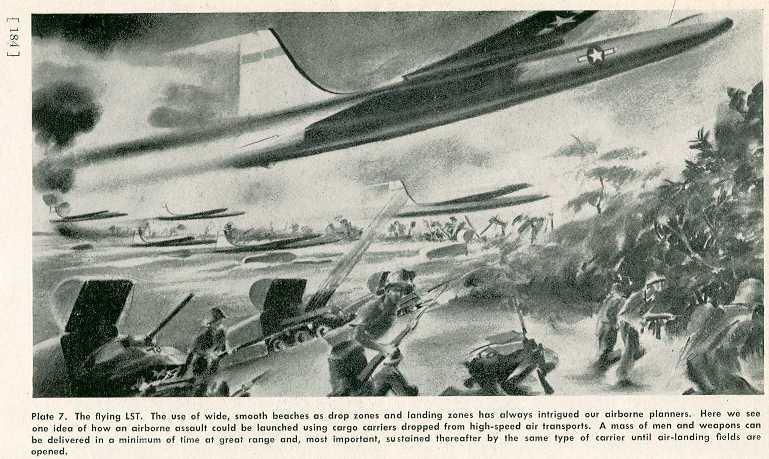

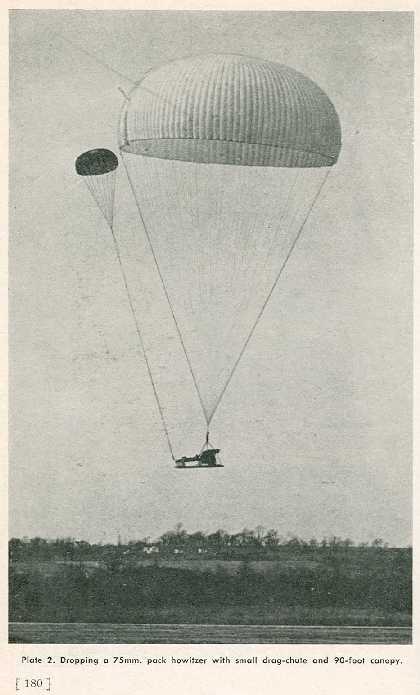

Gavin's paratroopers in WW2 were handicapped by civilian DC-3s in Army green (C-47 nickname: SkyTrains or Dakotas) that couldn't carry an intact platoon of men and easily caught fire without armor or self-sealing fuel tanks resulting in preventable losses of the 22 it did carry. Unable to parachute drop intact towed guns much less parachute dropping ground vehicles, this forced DC-3s to tow CG-4A Waco gliders that could carry either a towed gun or a jeep---but not both. The British in contrast, had larger Horsa and Hamilcar gliders that could carry both towed gun + prime mover and even Tetrarch or Locust light tanks or a pair of Bren gun open-top armored personnel carriers. They even had Halifax bombers that could parachute drop either two jeeps or a jeep and a towed gun from their bomb bays. For the Americans to get anti-tank guns to the fight they had to C-47-tow gliders--this meant large, open area landing zones had to be secured for the gliders to roll to a stop. Unlike the British Halifax bombers, DC-3/C-47s were without armament--the DC-3s were vulnerable to enemy fighter planes, so Gavin revolutionized airborne operations by night jumps which also protected the planes from anti-aircraft fires. To overcome the confusion of being in the dark, Gavin had his men memorize terrain features and sand table rehearse plans and contingency plans and be self-reliant and able to take the initiative in non-linear battlefield situations not be lemming marines. He created pathfinders to mark drop zones in the dark to improve assembly on top of objectives so they didn't have to walk far. Studying the German's troubles jumping from the very small JU-52 jump door, he exploited the large C-47 jump doors by having every Paratrooper jump complete weapons and equipment and minimize separate container drops to just 75mm pack howitzers in pieces but roped together for fast re-assembly. Because supplies could only be dropped through small fuselage openings or under-wing shackles, they were spread out all over and difficult to recover from open areas where the enemy could fire, and paras lacked vehicles with armor protection.

All of these conditions are not true today so there is no excuse why the U.S. Airborne is still handicapped! The current U.S. Airborne is a disgrace to the memory of the Airborne forefathers sitting on laurels bought and paid for by others and accepting self-serving handicaps that don't exist.

GPS insures that t-tail aircraft not only drop EXACTLY where we intend, but tell paras on ground exactly where they are. No need for rolling open fields for gliders to roll, a single nitrogen inerted fuel tank C-17 t-tail ramp aircraft can drop 80 tons on supplies on pallets, and M113 Gavin light tracked armored fighting vehicles can be on these pallets to not only recover the supplies with forklifts but also transport para infantry and anti-tank weapons ready-to-fire on the vehicle not towed---at 60 mph under armor protection. Air refueling enables fighters to escort our t-tail transports but our transport aircraft could and should be armed with their own air-to-air missiles and radar-guided cannon to swat SAMs in self-defense. Delayed opening timer parachutes with small drogue chutes would enable every para to jump if needed from high altitudes around 10, 000 feet above enemy air defense and have his main chute open at low altitude for a normal jump. Furthermore, with M113 Gavins paras need not land on top of heavily defended objectives but can take them by surprise from indirect drop zones. An American Airborne that foot-slogs or rides in road-bound, wheeled trucks when it has the most airlift of any force in human history---more than enough to have hundreds of amphibious, cross-country-mobile light tracked AFVs in use---is a disgrace.

All of the handicaps of the WW2 Airborne are solved, we just need people with 21st century minds in today's Airborne who want to execute 3D maneuver warfare as a Gavin "Sky Cavalry" not sit on their asses and do taxpayer-funded, seize & hold WW2 re-enactments pretending they are crippled when its all in their minds.

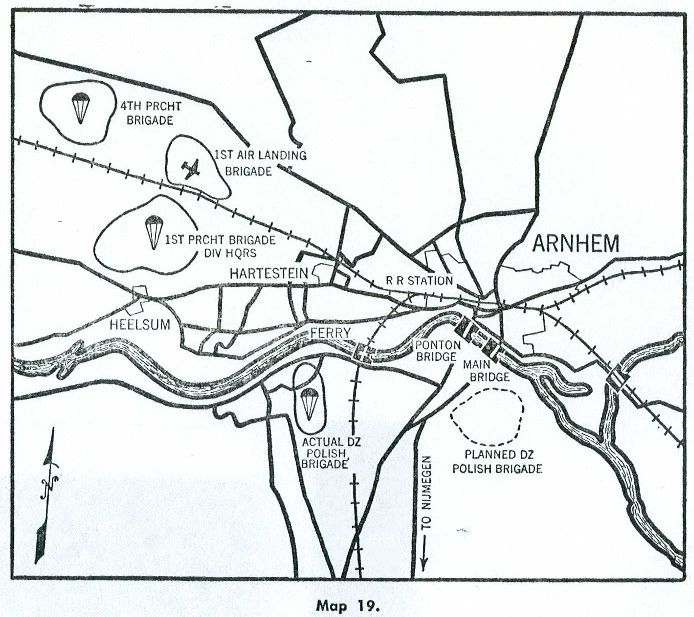

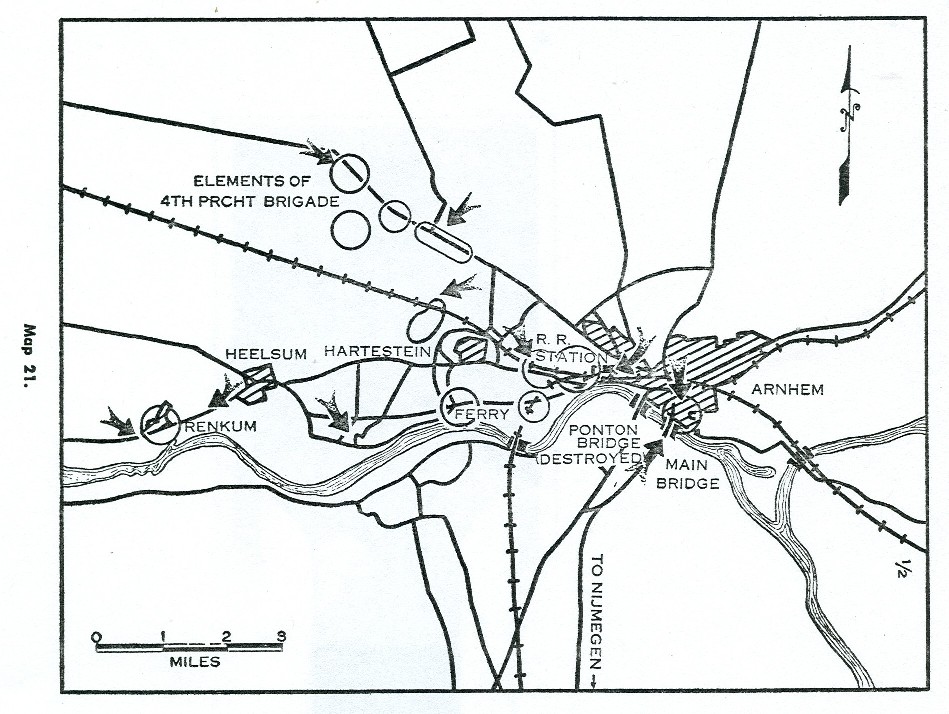

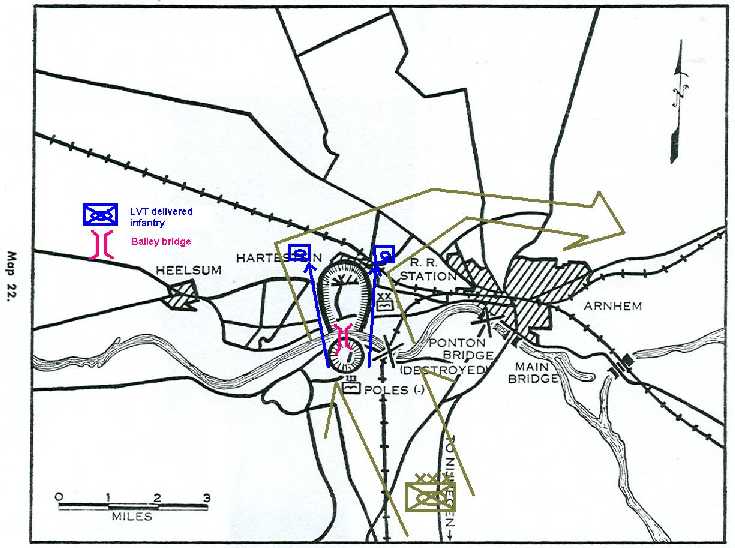

Furthermore, reading the war diaries of the British light troops surrounded near Arnhem below:

www.pegasusarchive.org/arnhem/war.htm

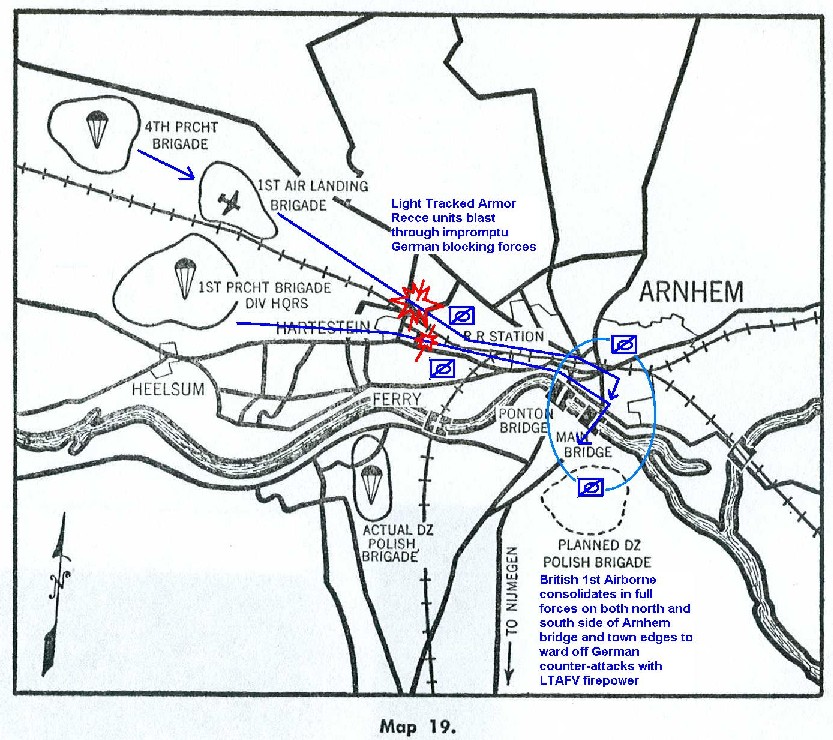

Its increasingly clear that 3D maneuver troops must have a "hard shell" in the form of their own light tracked armored fighting vehicles (LTAFVs) so enemy high explosive pounding of them will not attrit them to where they cannot hold a position. These light tracked AFVs should also have back hoes attachments so overhead cover fighting positions and hull-down vehicle positions can be created to bolster the baseline vehicle armor. LTAFV armored mobility also insures airdropped supplies---however they are scattered---can be recovered so even though the 3D force is in a non-linear situation with enemy all around, their fighting strength can be perpetuated indefinitely til the heavier 2D forces link up or they themselves implode the enemy resistance by their own maneuver actions.

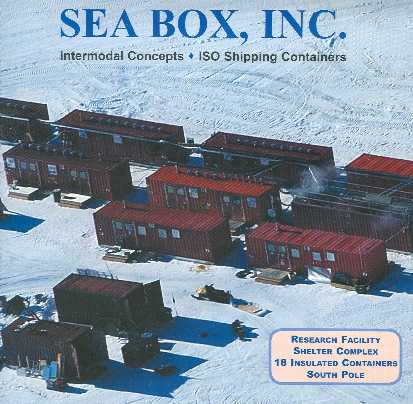

The other handicap light troops have against heavier enemy troops is that they don't have the supplies to artillery duel with them to keep them from laying down mortar, rocket and artillery pressures upon them since the latter has home field advantage of greater supplies in hand. The air-mechanized light force needs to never be outgunned and LTAFVs enable this because they can self-propel in a ready-to-fire manner tube and rocket/missile artillery that can through clever design keep the enemy's artillery shut down. Also notice how CAS fighter-bombers when overhead silence enemy guns---the AMS force should have its own "hip-pocket" air force of fighter-in-a-box (FINAB) aircraft in ISO container BATTLEBOXes delivered by KIWI pod aircraft right there on the scene operating from their airhead to do CAS as well as interdict enemy fighter-bombers and pesky UAVs from surveilling overhead to help target for the enemy.

FIRST EDITION

PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION by Major General William C. Lee USA (R) Page VII

CHAPTER 1: PARATROOPS OVER SICILY Page 1

CHAPTER 2: PLANS AND OPERATIONS IN THE MEDITERRANEAN Page 18

CHAPTER 3: BACK DOOR TO NORMANDY Page 37

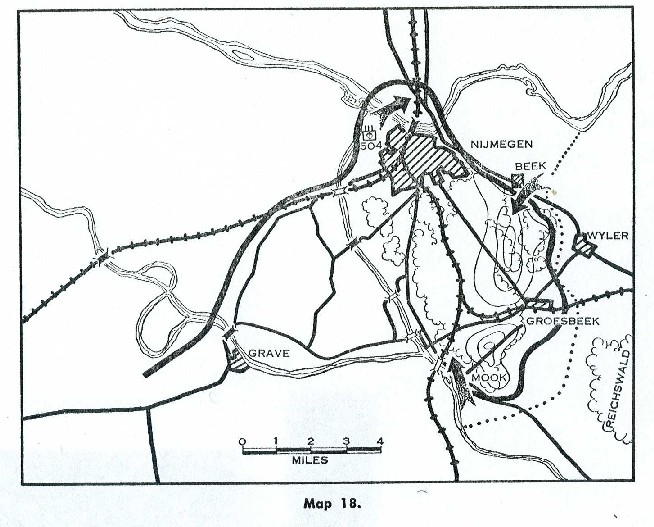

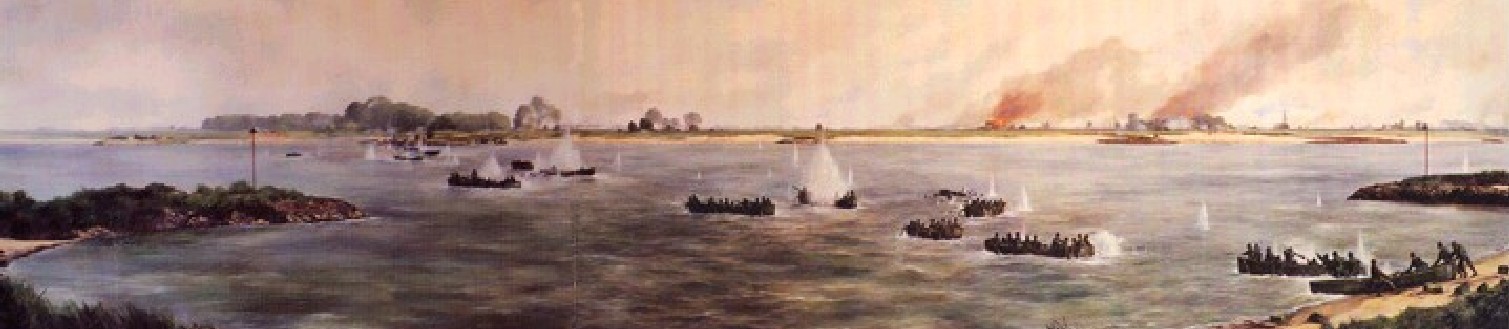

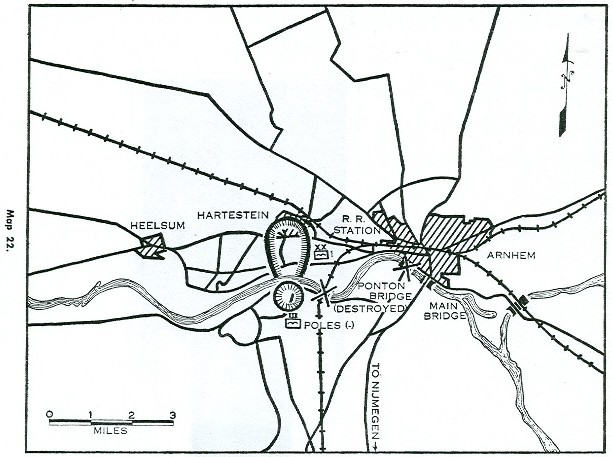

CHAPTER 4: HOLLAND: AIRBORNE ARMY'S FIRST TEST Page 68

CHAPTER 5: THE AIRBORNE OPERATIONS OF 1945. Page 123

CHAPTER 6: AIRBORNE ARMIES OF THE FUTURE Page 140

CHAPTER 7: ANTI-AIRBORNE DEFENSE Page 161

CHAPTER 8: THE USE OF AIRBORNE TROOPS IN THE FUTURE Page 170

INDEX Page 176

PHOTOGRAPHS Page 179

Page V

INTRODUCTION

THOUGH AIRBORNE WARFARE is new, the idea is old.

Throughout the centuries military men, watching the flight of birds or the drift of smoke on the wind, must have dreamed of the vertical envelopment. If we delve far enough back into history we would probably find that the ancient Chinese began the whole business by inventing the parachute. Records of old Peking indicate that they did. We know for certain also that in the fifteenth century, Leonardo da Vinci designed a parachute. In the eighteenth century, the Frenchman, Montgolfier, launched the first successful balloon, and late in the same century the famous European balloonist, Blanchard, made a parachute jump to save his life. After that, parachute jumps from balloons became common events and by the time the Wright brothers flew at Kitty Hawk the idea of the parachute was at least six centuries old. And it was over a hundred and fifty years ago, that Benjamin Franklin made his much quoted suggestion about the use of balloon-borne troops in war.

In more modern times, Mr. Winston Churchill and the late Brigadier General William Mitchell are both credited with advocating the use of parachute troops in World War 1. Even in relating it to World War II, we find that actual development of airborne warfare had progressed to a considerable extent at the time the Germans invaded Poland. By 1927, different armies of the world had carried out experiments of dropping equipment by parachute and transporting small numbers of fighting men by aircraft. In Texas the following year, our own Army dropped a small number of men by parachute with weapons and ammunition. In 1930, the Red Army dropped a group of military parachutists with equipment, and in 1936 it was reported that the Russians had dropped over five thousand parachute troops in a single operation during maneuvers at Kiev. By 1938, the Command and General Staff School of the U.S. Army was beginning to touch on airborne warfare in its theoretical tactical instruction. And, finally, in the Russo-Finnish War of 1939, came the significant

Page VII

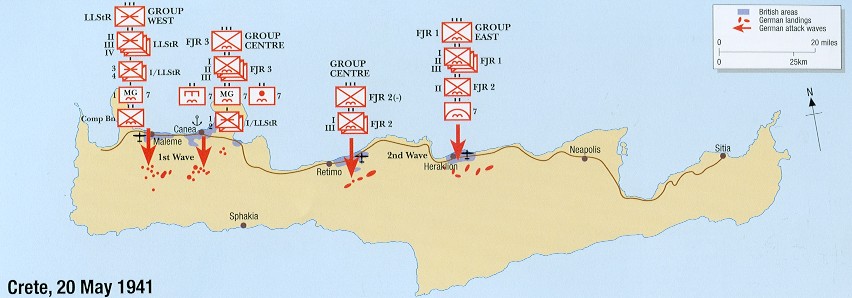

report that Russian parachute troops had been dropped in actual combat. At the outbreak of World War II, both the USSR and Germany had trained many thousands of parachutists, and the German Army had done considerable experimentation with gliders. Germany used airborne troops in large numbers with effective results in the 1940 invasion of Holland and the next year in the conquest of Crete.

Early in 1940, our own War Department had taken steps to develop American airborne units. Under the direction of Major General George A. Lynch, Chief of Infantry, in collaboration with the Chief of Air Corps, a program of development was approved and airborne troops for the first time became an integral part of the Army.

Thus it is a historical fact that airborne warfare, at least in the modern sense, was originated by the Russians and developed to a state of combat effectiveness by the Germans.

But it is also a historical fact that the American Army took this new instrument of warfare and, with the British, refined and improved it and unleashed upon our enemies airborne forces of such power and perfection as even they had not dreamed of.

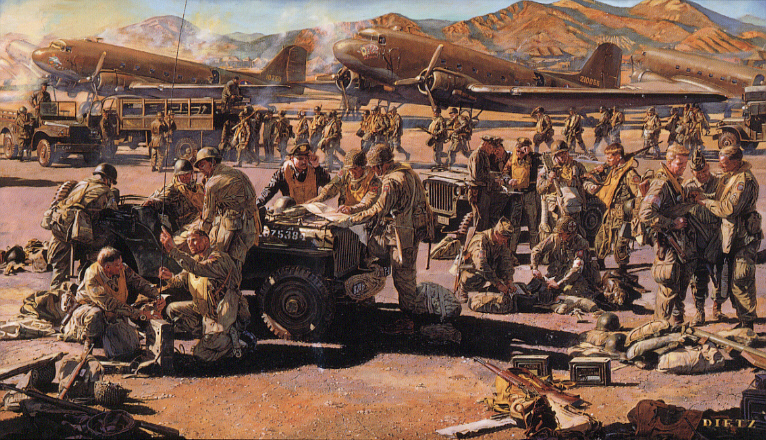

The pioneering phase of our airborne development began at Fort Benning, Georgia, with the organization of one small platoon of volunteer paratroopers. These pioneers, and the small group of intrepid aviators who worked with them, were the fountainhead of the mighty airborne forces that wrote such glorious pages in the history of World War II. The glory of those achievements rightly belongs to those who won the victories on the field of battle, but the unsung pioneers who blazed the early trails from the skies to the red clay hills of Georgia and the sand hills of North Carolina deserve at the very least a modest tribute. They too sweated out their fear of the unknown and charted new roads of courage. Many of them died in training that their successors might conquer in battle. When, in July 1943, the world was thrilled by the exploits of the 82nd Airborne Division in Sicily, there was not a man of the pioneer group whose heart did not swell with the fiercest pride in the realization of a dream come true.

Page VIII

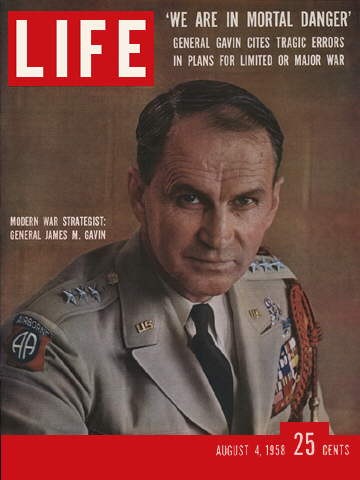

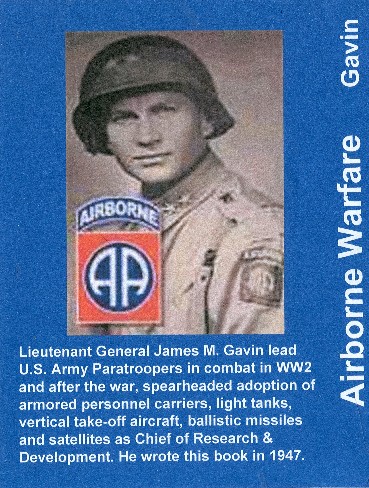

The author of this book was one of those pioneers.

It was a hot sultry day in August when Captain James M. Gavin, thirty four years of age, reported for duty with the Provisional Parachute Group at Fort Benning, Georgia. As a former enlisted man in the Regular Army and as a graduate of the United States Military Academy of the class of 1929, his service had been varied and broadening. His friends spoke exceedingly well of him, and he impressed his associates with his quiet dignified bearing, his appearance of lean physical toughness, and his keen and penetrating mind. His work as a battalion officer marked him for greater responsibilities and promotion to major, and then to lieutenant Colonel.

The rapid expansion of our airborne forces, immediately after the attack at Pearl Harbor, created many strange and complex problems and a vast amount of work, the activation of new units, the development of new types of weapons, all new equipment, new tactics and new methods of training were only a few of the arduous difficulties that confronted the builders of the new forces. Mistakes were made and many of them, but the building seems to have been fundamentally sound. No one man or no small group of men can be credited with this achievement. Many men and many elements made the project successful. But in the last analysis, the burden of building this great new force fell on the shoulders of the staffs of the Airborne Command of the Ground Forces and the Troop Carrier Command of the Air Forces, and on those staff officers in Washington who directed the planning on the higher levels. These were the architects and not the least of them was Gavin. In the building of this force, Gavin was a dynamo of intelligent energy. As the head of the Plans and Training Section of the Parachute Group, and later the Airborne Command, he wrote many of our basic training doctrines and our first textbooks on airborne training and tactics. By late 1942, he had received his colonelcy and the command of his own regiment. In January 1943, his regiment was assigned to the 82nd Airborne Division, and on the night of July 9 of that year he commanded the airborne

Page IX

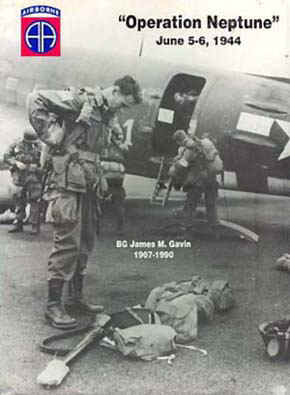

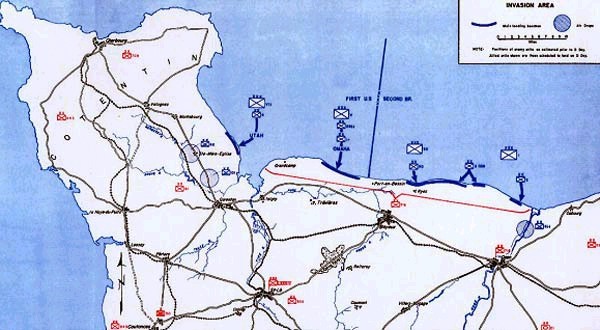

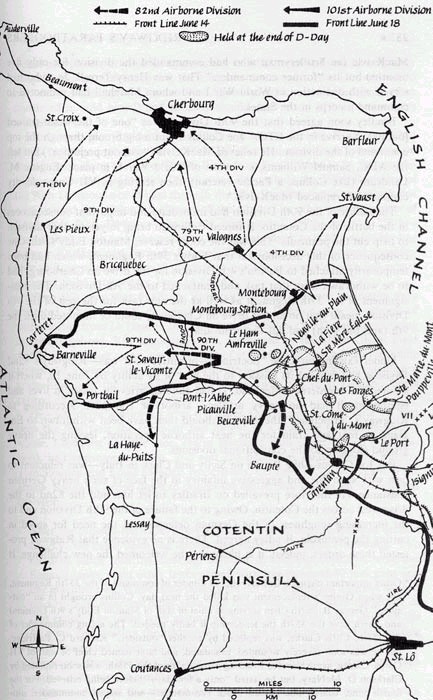

combat team which spearheaded the American assault of Sicily. This book is Gavin's story of that assault as well as all the airborne combat that followed until the end of the war, and it is his interpretation of those events as applied to future war. From Sicily to Italy to England, Jim Gavin continued to pioneer, and to win his battles. In rising from Colonel to Brigadier general he continued to learn warfare. As airborne adviser to the Supreme Allied Commander in London, he was determined that costly mistakes made in Sicily must not be repeated in Normandy. Upon his arrival in England from Italy, he was immediately enmeshed in the intricate details of operational plans of the Allied airborne forces, working closely with the British and American airborne commanders. The success of those forces on D-Day is all the evidence needed of the brilliancy of his work. As assistant division commander of the 82nd Airborne Division he led the assault parachute echelon of that division into Normandy.

And later, on the elevation of Major General Matthew B. Ridgway, the division commander, to the command of the Airborne Corps, Gavin was made division commander and a Major General at the age of thirty-seven. He commanded the division throughout the rest or the war in its brilliantly successful operations in Holland, Belgium and Germany. As a young and dynamic commander he represents, to my mind, the type of American leadership produced in our greatest war. He writes here of a revolutionizing experiment in the art of war. Americans will do well to read his story and study his conclusions with care. There are many of us that served in our armed forces during the recent war who are old enough to remember the days of the youth of the gasoline engine. We are not old men yet as years are counted, and our memories are young enough to retain vivid recollections of the horseless buggies and flying crates. But in these days when the skies of the world are flecked with the swift, sleek machines that have telescoped time and distance, it seems a marvel that during one short lifetime the coarse oil of the earth could have revolutionized so completely our way of life and our manner of warfare. Perhaps Soldiers of past ages have always felt the same about the revolutionizing inventions of their times. Perhaps the wheel, gunpowder and the steam engine created in contemporary military men the same consciousness of accelerating destructiveness that many of us feel today. But in the past, new weapons of war have always brought new means of defense and, except for temporary periods, the delicately balanced scales of attack and defense have tended to balance. In the past, too, time moved more leisurely than now. It took hundreds of years to revolutionize warfare through the use of gunpowder, but the internal-combustion engine did it more recently in less than half a century. And now atomic energy and new methods of propulsion are increasing vastly the tempo of war with shocking suddenness. The scales are out of balance and victory favors the attack. No nation can consider itself secure from devastating aggression, and those of our leaders who fully comprehend the danger are filled with a sense of urgency to produce a pattern of peace that will endure.

But until the statesmen of the world can devise such a peace we of America must read the signals of danger and build our defensive forces accordingly. In the rebuilding of our armed forces, we must project into the future the significant developments of our past experiences. Changes in organization and equipment are indicated by certain developments in many components of our armed forces. For instance, airborne warfare and atomic energy have come out of this last war to change many of our former strategic concepts of the time and space factors of land warfare. These developments are in their infancy, crude and immature, their surfaces hardly scratched. We read that already designs are planned for missiles, aircraft and their adjuncts which startle the imagination even after what it has known. As scientific development gradually brings these craft and these weapons to completeness and perfection, the future employment of all land forces becomes inescapably involved. And should war scourge this earth again, vast armadas of the air will fly whole armies and their accouterments over hemispheres and oceans in hours instead of the days and weeks and months it formerly took to move them overseas.

Page X

To understand modern war one must have seen it at first hand, shared in it, shouldered a part of its terrible responsibilities, and known the cost in toil and blood and destruction. Our future army and future ways of war must be built on the knowledge of those who have done these things, and it is from them we must learn. They are the experts. This book is by an expert-an expert in airborne warfare. It is surprising that so very little has been published for public reading about such a significant and outstanding military development, especially in its relation to our future defensive needs. General Gavin's book helps greatly to fill this pressing need and I know of no man better fitted than he is to write it, either by experience or the ability to think clean and clear. His qualifications are complete.

WILLIAM C. LEE

Major General, USA, Retired

Dunn, North Carolina

8 June 1947

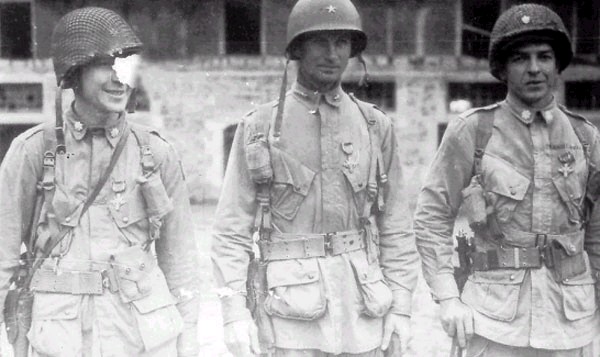

Generals Gavin, Taylor and Lee right after the end of WW2

Page XI

CHAPTER 1: Paratroops Over Sicily

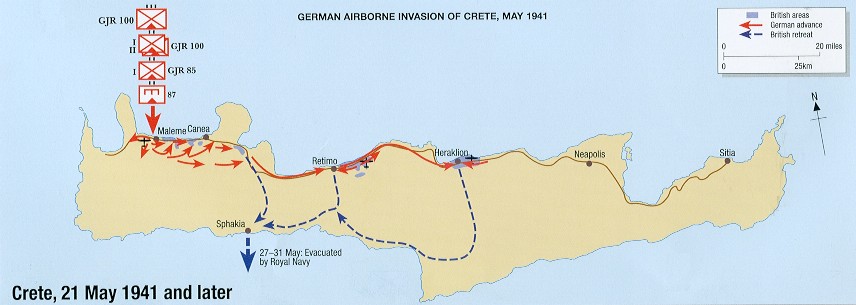

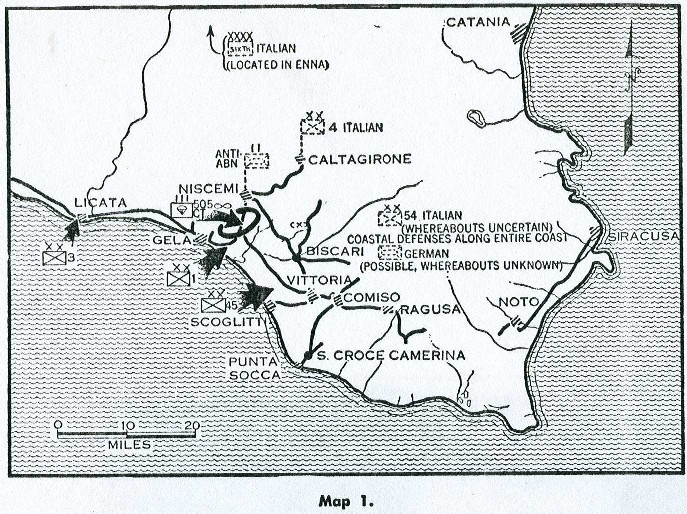

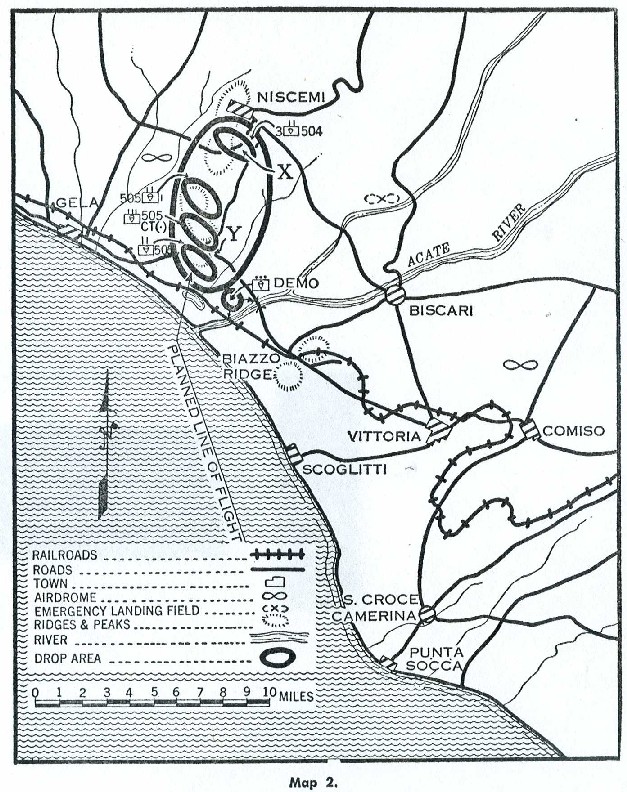

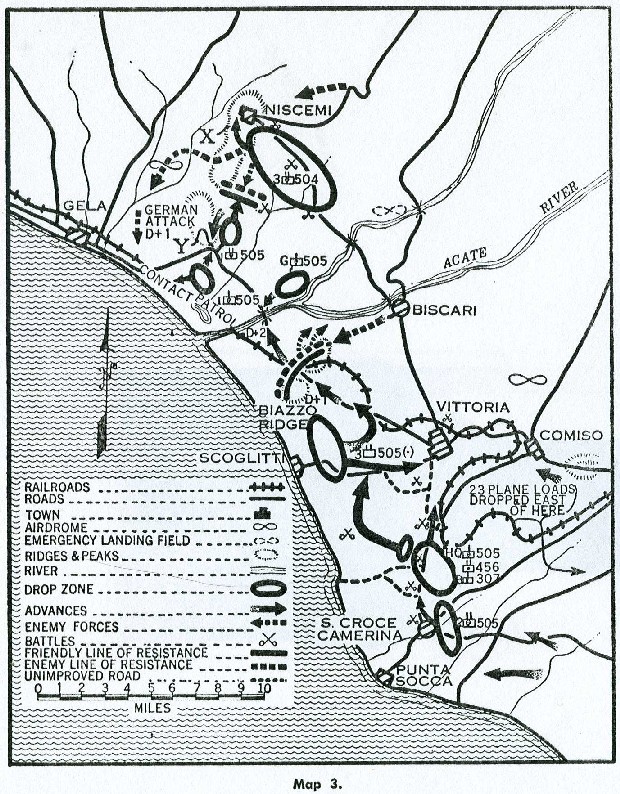

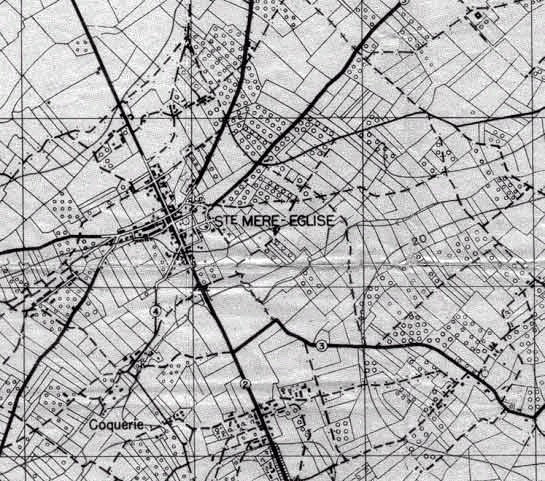

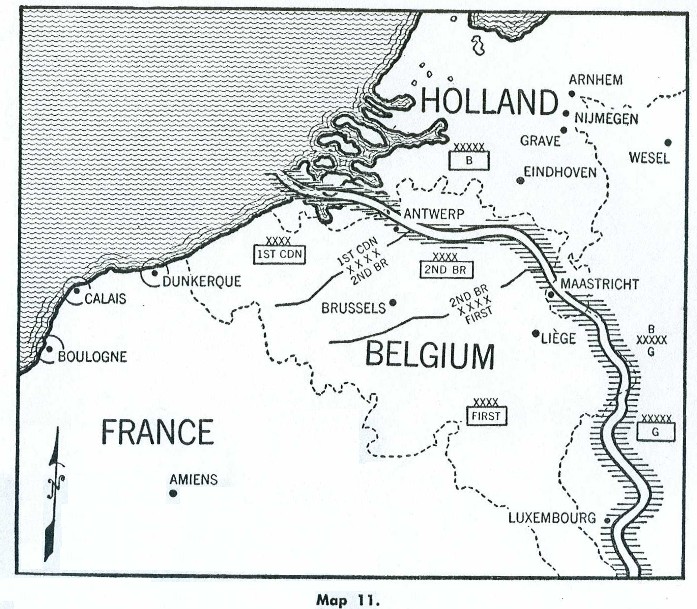

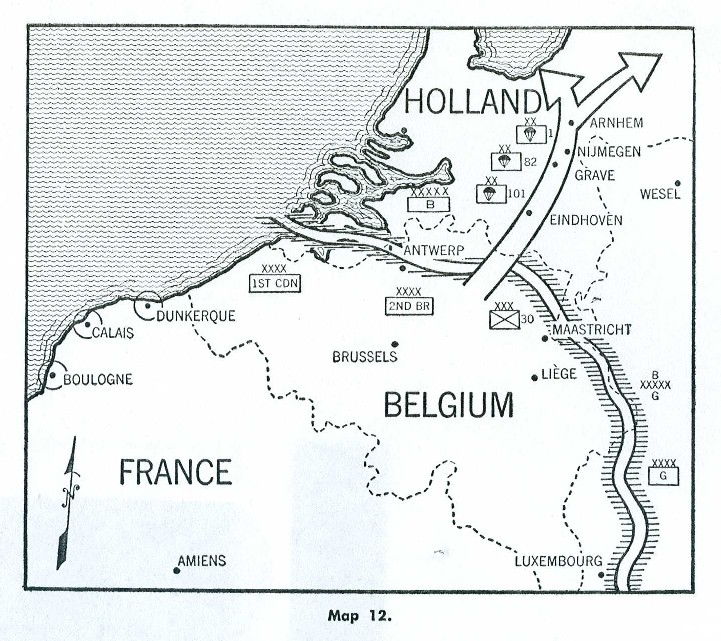

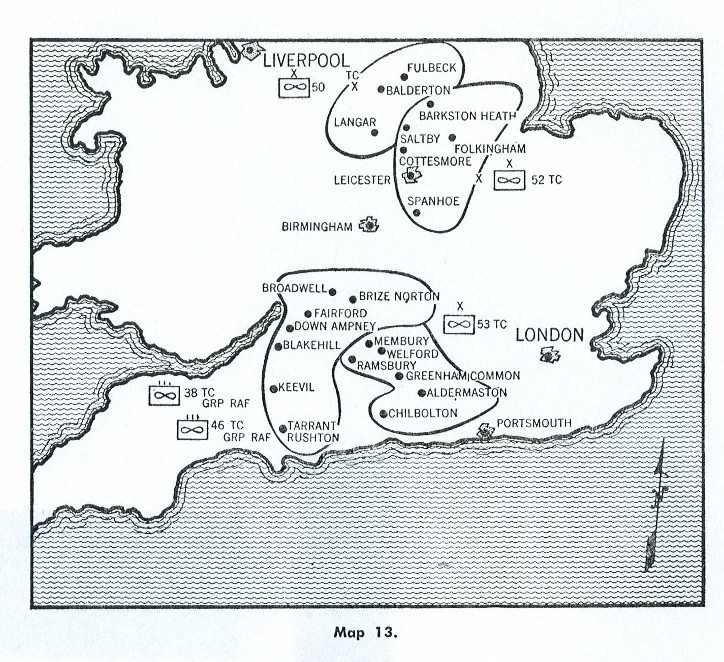

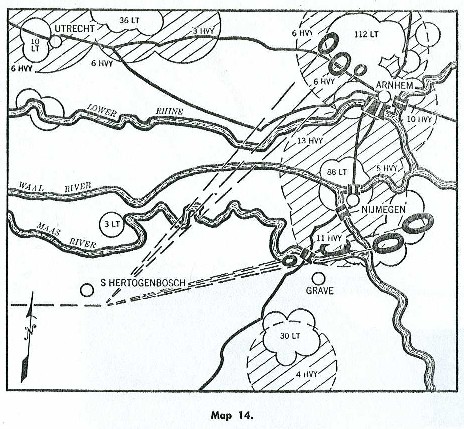

SICILY IN JULY OF 1943 was the birthplace of American airborne technique. It was, as well, the crucible into which were thrown the brain storms, the cocktail cerebrations, and the intensely cherished unorthodox combat tactics of a young army. Theories originally conceived, nurtured and brought to apparent maturity without the test of battle were exposed to their first test. How well they fared, how well they fought, and what our airborne forces accomplished are questions not even partially answered to date. But the toddling tot that later became the First Allied Airborne Army was born in Sicily and survived a very rugged delivery. This Airborne Army was conceived in the planning staffs and headquarters of the North African Theater of Operations and the U. S. Seventh Army. The final Sicilian invasion plan envisioned an amphibious assault at Licata, Gela, and Scoglitti (see Map 1) by the U. S. 3rd ["Rock of the Marne"], 1st ["The Big Red One"] and 45th ["Thunderbird" National Guard] Infantry Divisions. The II Corps, commanded by General (then Major General) Omar N. Bradley, consisted of the two divisions on the right, the 1st and 45th. After landing, the airborne troops were to be attached to this corps. The plan of invasion called for one parachute combat team (CT) of the reinforced 82nd Airborne Division to drop between Caltagirone, where large enemy reserves were known to be, and the 1st Division's beaches. After the D-Day landings, the combat team was to be built up by successive air and sealifts in the zone of the Seventh Army [commanded by General George S. Patton] and participate in the conquest of the island. The 505th Parachute Combat Team (reinforced) made the initial assault with orders to seize key terrain south of Niscemi for use as an airhead and to block enemy movement toward Gela from the north. It was to destroy enemy communications and deny by fire the use of Ponto Olivio airfield. Particular attention was to be paid to the strong point at "Y" (see Map 2). This locality, heavily wired and mined, consisted of sixteen mutually-supporting reinforced concrete pillboxes and blockhouses. The strong point controlled all traffic on the Gela-Caltagirone and Gela-Vittoria

Map 1

roads. The road net at "X" also was to be seized, blocked, mined and held. After contact with the 1st Infantry Division, the CT was to assist it in its advance. The 505th Parachute Combat Team (reinforced) consisted of the following: 505th Parachute Infantry Regiment; 3rd Battalion, 504th Parachute Infantry; 456th Parachute Field Artillery Battalion; Company B, 307th Airborne Engineer Battalion; and Signal, Medical, Air Support, and Naval Support detachments. The force totaled 3,405 troopers, requiring 227 x C-47s for transport. The mission posed a number of problems never before encountered. Should the transports fly in formation as other American combat aircraft were being flown, or should they fly "bomber-stream" as the British were flying? Should the drop take place before or after the amphibious landing, or at the same time as the landing? Should the drop take place under cover of darkness, or in daylight hours? There were a number of opinions on these problems, all of them supported by strong statements and the firm belief of our critics in their own opinions.

Map 2

Flying the transports in formation offered some advantages. It would permit a quick mass delivery of the troopers on their objectives. Offsetting this was the inflexibility of formation flying. This might prove costly in the event of hostile interception and' heavy flak. Formation flying would require intensive pilot training. On the other hand, an accurate delivery of troops from a formation would require fewer skilled navigators and the troops

Page 3

would be delivered en masse, over the objective, and not by single drops. Even if delivered at the wrong area, each unit would still be a complete force. It was finally decided to fly in nine-ship formations, with approximately one and one-half minutes between each flight. Serials contained up to fifty-two airplanes. The column was thirty-six minutes long. The timing of a drop is always a difficult problem to decide. Training experience had led us to believe that at least a half-moon would be necessary both for the flight and the drop. Moonlight would greatly facilitate the assembly and reorganization of the troops. On the target date selected, July 10, 1943, the moon would be almost full. The ideal solution would be to complete the dropping of all units before the moon set. This would then give us several hours of darkness to carry out defensive organization and operations against the enemy. We believed that the risk of interception by hostile fighters eliminated the possibility of a daylight drop, and by day extensive enemy ack-ack would cause heavy casualties. So, proper timing made it necessary for the parachute troops to land several hours before the amphibious troops. The decision was made to drop the leading airborne elements three hours and fifteen minutes before the beach assault.

A night parachute operation had never before been attempted by any army so organization and training for it offered many new problems. The many intangible and indefinable difficulties of fighting at night in hostile territory when every object appears to. be and often is the foe, all had to be overcome. Rapid assembly and reorganization of the troops appeared to be the greatest. Lacking combat experience, it was difficult to determine just how much security to sacrifice for speed. The actual combat proved that the assembly and reorganization were conducted too cautiously. Many visual aids could have been used to great advantage. Intensive, thorough training that built up boundless confidence in every man and in his unit was the only solution. The basic load of combat equipment for the individual parachutist was checked and rechecked. Complete plane loads were

Page 5

weighed and checked in every detail. The complete loads of all units from squad to regiment were tried in all possible combinations, to arrive at the most efficient combat load. The complete lack of combat experience brought forth many original ideas. All were considered, tried, and either accepted or rejected. Replicas of the operational areas, particularly strong point "Y," complete to scale, were set up near Oudjda, French Morocco. Troops attacked with ball ammunition, and, as far as possible, realistically rehearsed their combat roles in every detail. In the final combat team drop rehearsal, token loads were dropped to check pilot accuracy. If the spirit of the troopers and their desire to fight the German was any criterion, they looked like winners. But the actual mechanics of night assembly and reorganization and initiation of combat still left much to be desired. In the final pay-off, this requires intensive training and much experience to be done well.

On June 10, the CT commander [Colonel Gavin-EDITOR], accompanied by two battalion commanders and three commanders from the 52nd Troop Carrier Group, flew to Malta, where the group made a night reconnaissance of the operational area. The reconnaissance was flown under conditions exactly as they would be one month later, the night of D minus 1 and D-Day. All check points and terrain showed up clearly in the moonlight, exactly as we had memorized them from the photographs. There was little reaction from the ground defenses. Considerable flak, however, came up from Ponto Olivio airdrome and vicinity, and several searchlights scanned the sky from around Biscari. All units were dispersed in bivouacs in the Kairouan take-off area ready to go, by July 4.

Final briefings were held and the planes took off exactly on schedule the evening of July 9. The final order included a paragraph that soon had real meaning. All pilots and troopers were told that every jumper and every piece of equipment would be dropped on Sicily. No one would be returned. If a pilot and jumpmaster could not locate the exact drop zone, the troops would jump and fight the best way they could.

Page 6

These orders were followed.

What happened after the take-off can best be told by some of the participants. This is the story told by Captain Edwin M. Sayre, who commanded Company A of the 505th, and was probably the first to land on the island:

A Company took off at 2030 hours for the first check point at Malta. I do not know whether or not we saw Malta as I had never seen it before, but when we were due to arrive there I thought I saw a light. In any event, we continued and about fifteen minutes before the scheduled jump time, we could see flashes of gunfire through the door of the plane, on the left. This surprised me, because I had expected to see Sicily appear on the right. There was considerable firing and the pilot turned to the right away from the island. We figured out later that we had hit the coast of Sicily somewhere between Noto and Siracusa. (As a matter of fact, 23 plane-loads [506 men] of this 1st Battalion of the 505th jumped near Noto where they met the British Eighth Army and joined in the ground fighting with it.)

We circled to the right, going out to sea, and came back in toward the southern coast. We followed along the shore until we saw the lake which was a check point. The squadron then turned in toward the island. About one minute after the turn, we met heavy ack-ack, apparently coming from the Ponto Olivio airdrome, The squadron turned to the right to avoid this fire and shortly thereafter the green light was given. It was about 0035. "The planes were under heavy machine-gun fire when we jumped and there was a lot of firing on the ground. By 0230, I had assembled fifteen men from the company and contacted the battalion executive officer. Company A was to attack a point from which about four machine guns were firing. We first attacked at 0300. The point from which the machine guns were firing was a garrison surrounded by pillboxes and was pretty strong. The attack was held up until about 0530, at which time fifty more men had been assembled. The attack was resumed and the garrison was killed or captured by 0615. It was held by one hundred Italians, with German noncoms from the Hermann Goering Panzer Di-

Page 6

vision. We could hear a lot of fire in the valley-up toward Niscemi and down toward the beach. At about 0630, Lieutenant Colonel Gorham, the battalion commander, arrived with about thirty troopers from headquarters. He ordered us to consolidate our position, since it commanded the road leading from Niscemi to the beaches.

At about 0700, a German armored column was seen about 4,000 yards away, coming from Niscemi. It was preceded by a point of two motorcycles and a Volkswagen. We let the point come into our position and then killed or captured the men. The armored column stopped about three thousand yards away when the point was fired on. Our position was then attacked from the front by two companies of Germans. We let them approach to within one hundred yards and then pinned them down in the open ground. Most of them were killed or captured.

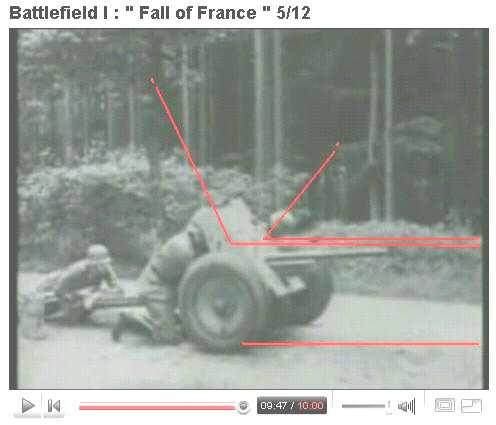

www.youtube.com/watch?v=YjVpKS9n2n8

www.youtube.com/watch?v=YjVpKS9n2n8

At the same time, tanks hit us from the flank. Two of six attacking tanks were knocked out and two more were damaged by a bazooka squad. The tanks withdrew. During this fight, Colonel Gorham sent patrols to the high ground which was the regimental objective, and to the "Y". They reported that the crossroads at the "Y" was guarded by about thirty Italians in pillboxes surrounded by barbed wire. There was no one on the high ground.

Colonel Gorham moved our force to the high ground, using about fifty prisoners to carry the wounded.

After we had organized on the objective, a large part of our force moved out to capture strong point "Y", leaving about a squad and one officer to cover us from the north. When about four hundred yards from the strong point, heavy naval gunfire was seen falling about one hundred yards north of the pillboxes, but it could not reach the pillboxes which were in defilade. One of our Italian prisoners was told to go to the pillboxes and ask for their surrender. The occupants were told that if they did not surrender we would bring the naval gunfire right down on the pillboxes. We didn't have any communication with the Navy, but the men in the pillboxes didn't know that and surrendered. Our men moved into the pillboxes at about 1045.

Page 7

A few minutes, later four German tanks approached from the north. When troopers in the pillboxes fired on them, they withdrew. At 1130, scouts from the 2nd Battalion of the 16th Infantry, 1st Division, contacted us at strong point "Y". Colonel Gorham then attached all of our troops to the 16th Infantry and we advanced to the north. Shortly after this I [Captain Sayre] talked to Major General Ridgway by telephone and reported that the regiment had accomplished its mission, capturing strong point "Y" and seizing the high ground northwest of it.

We continued the attack with the 16th Infantry, finally capturing some high ground about a mile north of the crossroads, toward Niscemi, at 1900. The battalion remained in place that night and launched another attack at dawn, July 11, its objective being a hill to its immediate front. About one hour after the hill was taken, a strong German counterattack, consisting of about a battalion of infantry and about twenty tanks, hit our position. When it looked like the tanks would overrun us, a number of the men moved back. We drove the German infantry off but the tanks managed to get through us.

The next night we again attacked toward Niscemi and again, at about 0900, the Germans counterattacked, using several Mark VI tanks plus some [light] Mark IVs. We had good artillery support from the 1st Division and the tanks were finally stopped about one hundred yards from our position. During this action, Colonel Gorham was killed while engaging a tank. The following morning Niscemi was captured by the 1st Division and we were ordered to rejoin our combat team.

The Combat Team commander [Colonel Gavin-EDITOR] told this story:

I flew in the lead ship of the 316th Troop Carrier Group, commanded by Colonel McCauley. All preparations went according to plan. Just before I boarded the plane a messenger from base operations informed me that the latest reports showed a 35-mile-an-hour wind over the target area. [Usually training jumps are cancelled if the wind exceeds 15 mph.] But there was nothing we could do about it. Our ships rendezvoused over the take-off area and we started for Sicily. I had memorized the route and times and knew we should

Page 8

pass the island of Linosa at 2230. But 2230 came with no sign of Linosa. I thought perhaps we were slightly off course and correction would be made before reaching Malta. Malta was a big target and certainly would not be missed. The lights would be on, so I expected no difficulty in recognizing it.

The troops were resting easily, overloaded with equipment but anxious to go. A few were sleeping. It was 2300 but there was no sign of Malta. Up to this point, we had seen no recognizable landmarks. The ocean appeared rather choppy. After flying on for some time, I became concerned about our location, and after a discussion with the navigator, it was decided that we must have missed Malta, since it was long overdue. Figuring the course that would bring us to Sicily if the 35-mile wind had blown us eastward, we made a left turn and the flight continued. Around this time we saw a number of vessels, all apparently headed for Sicily. They gave us an anxious moment, since we knew that we would probably draw fire if we flew over any ships. Our route had been changed several times to avoid-these convoys.

About midnight, the crew chief told me that land was in sight, evidently Sicily. Soon we could see occasional fires and tracers.

We turned and flew parallel to the coast for some time. All troops prepared to jump and we turned in toward the coast. I had memorized all the terrain surrounding the landfall we should have passed. We were supposed to fly over a large lake, the one I had already flown over a month before. But we saw none of the recognizable landmarks. It was almost time to jump. Finally the green light in the plane came on and we went out. There was some scattered firing on the ground when we left the planes. One C-47 crashed and blew up on the drop area.

The firing increased. Buildings and trees were moving by swiftly as we came in for the landing, a sure sign of a strong wind. Immediately after landing, reorganization and assembly were begun but many men were missing. After half an hour about 15 were assembled. We could hear a great deal of firing from all directions. We captured an Italian soldier but obtained no worthwhile information. We started to move toward where the drop

Page 9

zone should be. A few men were picked up during the night. My group finally consisted of myself, S-3, S-1, and several enlisted troopers. A number of the troopers had been injured in landing and fell by the wayside. Others were lost or engaged in small fights.

Up to this point, just before daylight, we had seen no familiar landmarks and we weren't sure whether or not we were actually in Sicily. Just before daylight, heavy naval shelling opened up to the west and south. We were happy to see it, since it proved at least that we were actually in Sicily. Based upon the location of the shelling and my knowledge of the naval support plan, we started west at once. About two hours after daylight, we engaged in a small-arms fight at close quarters. One trooper and three or four of the enemy were killed. Firing could still be heard in the surrounding country where parachutists were fighting wherever any enemy could be found.

Because of the hostile attitude of the civilians, and our inability to engage any major enemy force on favorable terms, we holed up just before noon. We moved out toward Gela before darkness and at 0230, we met Company I, 179th Infantry, 45th Division [National Guard], about five miles southeast of Vittoria. This was our first information of our exact location. We passed through Vittoria about 0500, picking up a number of troopers, and continuing toward Gela. Several miles west of Vittoria, we met the 3rd Battalion, 505th Parachute Infantry. We pushed westward. Our first contact with the enemy in force was where Biazzo Ridge crosses the Gela-Vittoria road.

About a mile short of the ridge, some Soldiers of the 45th Division stopped me and said that the Germans held the road ahead and that we should not try to go through. The situation looked about just right to take them on, since we now had about two hundred and fifty paratroopers, so we continued our march. A German motorcyclist, with an officer in a sidecar, was surprised and captured. He told us that large German forces were apparently astride the Gela-Vittoria road and moving in strength from Biscari to Vittoria. We could hear a great deal of firing. Since the

Page 10

road had to be opened to the 1st Division, where we hoped the rest of the 505th Combat Team was engaged, we continued our advance. German forces occupied the ridge and placed heavy small-arms fire on our leading elements. The Germans soon were driven off the ridge, which then was occupied by a platoon of Company B of the 307th Airborne Engineer Battalion.

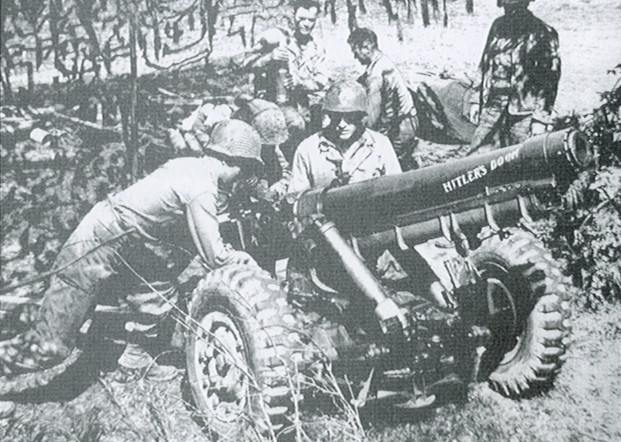

Our entire force, reinforced by one platoon of Company L, 180th Infantry, 45th Division, several Sailors, and other miscellaneous groups which happened to be around, attacked toward the Acate River, in the face of intense fire. The Germans reacted violently. They counterattacked at noon, with about six Mark VI [Tiger heavy] tanks. These overran the assault elements of the parachute force and penetrated as far as the combat team CP, just over the top of the ridge. A staff officer dispatched [S-1 Major Al Ireland by bicycle] to General Bradley's II Corps Headquarters obtained a liaison party from a 155mm battalion (189th Field Artillery), also a company of Sherman [medium] tanks and a Navy artillery support party. At 1600, the Navy and the 155s fired on the Germans and quieted them down.

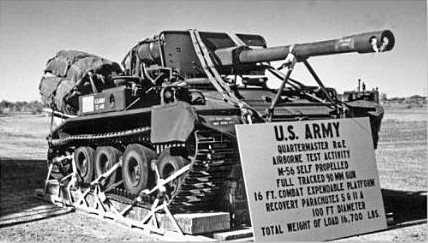

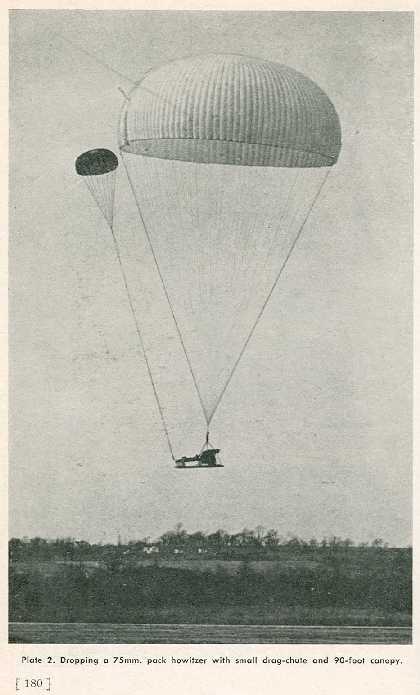

DOWNLOAD U.S. Army Field Artillery Journal ARTICLE "Cannons under canopy":

www.combatreform.org/fajournalcannonsundercanopyJULAUG2000.pdf

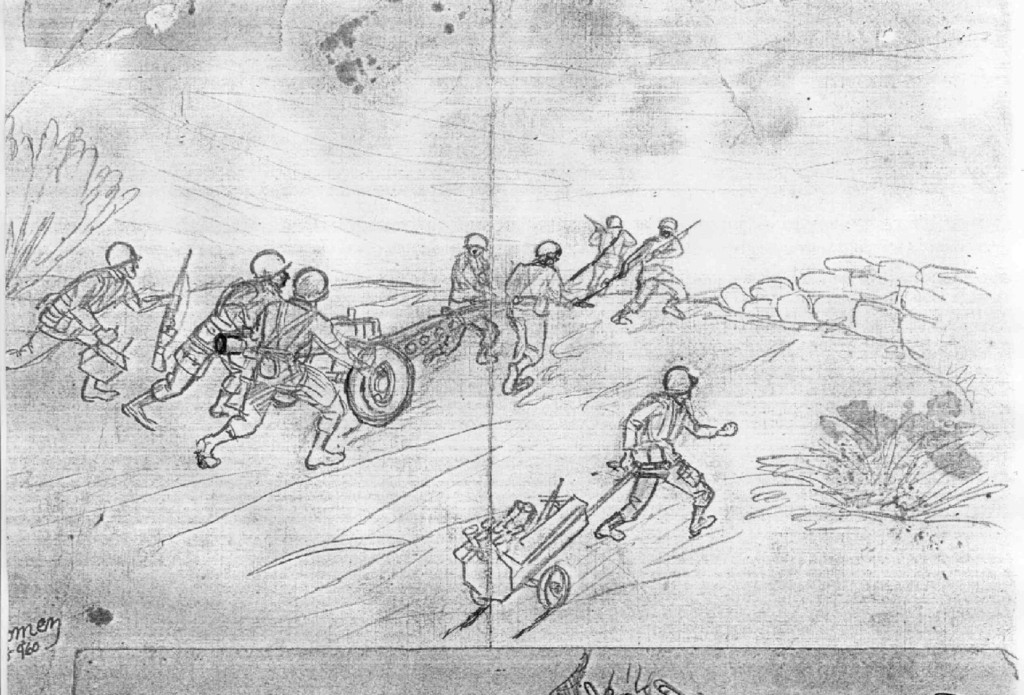

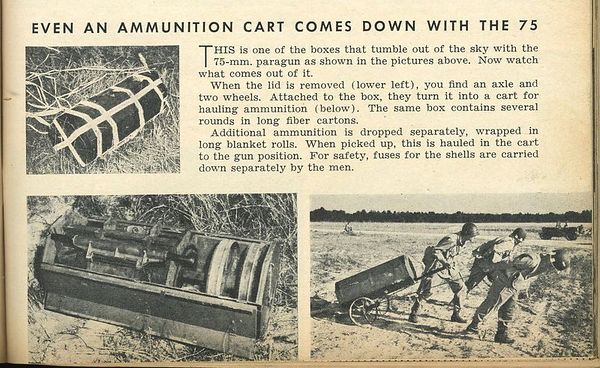

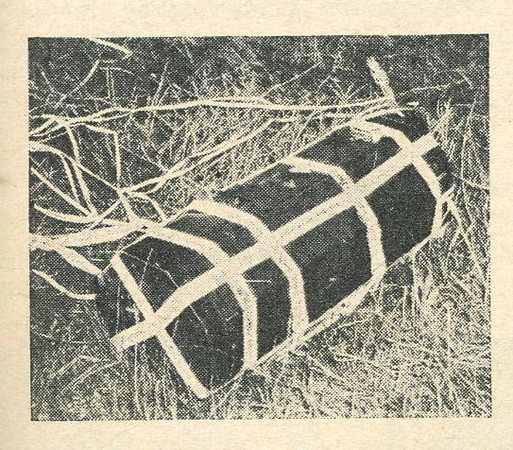

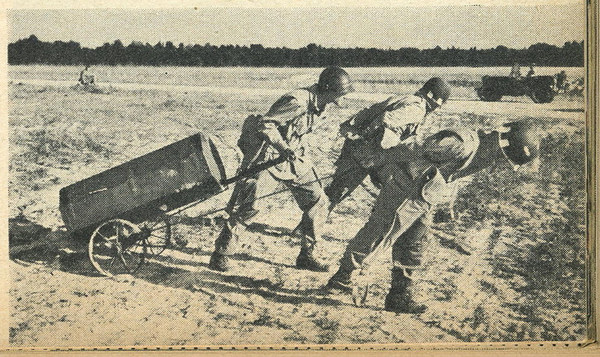

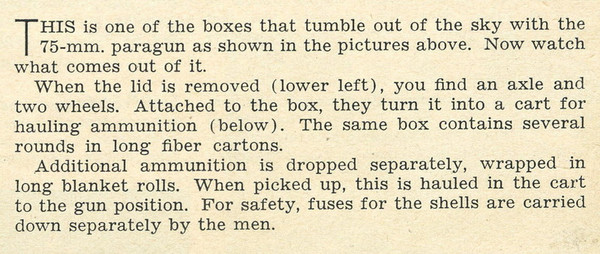

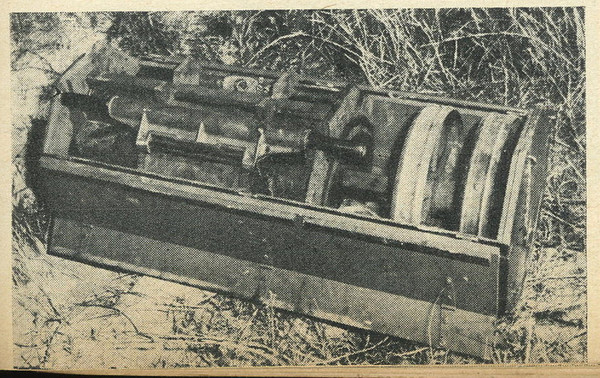

Gavin and his comrades got the idea of equipment containers made into carts from studying the German Airborne victory on Crete in 1941 though not being too dependant on them, by having each Paratrooper jumping in his own equipment using lowering line loads.

Up to this time we had had no artillery support except two 75mm pack howitzers, which were being effectively, used as antitank (AT) guns.

German prisoners all said that their force consisted of a battle group from the Hermann Goering Panzer Division that was moving from Biscari toward Vittoria together with another group moving from Niscemi to Gela. Some of the first prisoners taken said they had been in Sicily for several years in Luftwaffe ground crews and had just been transferred to the Hermann Goering Division. All German troops fought exceptionally well. All this day, July 11, our parachute force was being augmented by troops coming from the southeast. Approximately one hundred men, mostly engineers of the 307th Airborne Engineer Battalion, had joined by dark.

As a final effort on this day, we planned an attack to jump off at 2030, in which we would use every available man, clerks, runners and what not, this attack supported by the company of Sherman [medium] tanks which had just arrived. The attack jumped off on schedule and completely overran the German positions, cap-

Page 11

Map 3.

turing one Mark VI tank complete and destroying three others which were abandoned by the Germans during the night on the road to Biscari. We also captured twelve six-inch Russian mortars and a number of trucks, motorcycles, and a large quantity of small arms and ammunition. By 2200, we had consolidated our gains and at daylight we continued to the Acate River, where we were held up by orders from Corps Headquarters. The next day a pa-

Page 12

trol got through to Gela and contacted the remaining elements of the 505th Combat Team, which had fought with the 1st Division. By this time, our force on Biazzo Ridge was about two thousand strong. We reported to the commander of the 82nd Airborne Division, Major General Matthew B. Ridgway, at his CP [command post] three miles east of Gela, and the combat team came under division control.

Because of the 35-mile wind, the 505th Combat Team had flown considerably to the east of its originally planned course. Thus Malta was missed, and most of the troop carrier units arrived at the east coast of Sicily, with landfall first appearing on the left, instead of approaching the southern coast, with landfall first appearing on the right, as anticipated. When the planes did arrive over the island, the dust and haze stirred up by the pre-invasion bombing had obscured most of the check points and drop zones.

In addition, many pilots were under heavy fire for the first time.

In spite of these handicaps, they made a courageous effort to deliver their troops to the proper drop zones, some of them circling out to sea and making several run-ins. The collective limitations of bad weather, ground haze, inexperience and lack of better navigation means made the task almost impossible. The troops were delivered as shown by Map 3.

The 3rd Battalion of the 504th Parachute Infantry, the unit farthest north, was scattered widely over an area generally southeast of Niscemi. In the subsequent fighting, the paratroopers destroyed all enemy communications that they could get their hands on, attacked enemy troops and vehicles along roads, and denied the enemy the use of the road from Niscemi to Biscari. One group of between 95 and 100 troopers, under Lieutenant George J. Watts and Lieutenant Willis J. Ferrell, organized a strong point around a large chateau at the southern side of Niscemi. The Germans made repeated attempts to dislodge them, and failing to do so, tried to ignore them and by-pass the chateau, which overlooked the main Niscemi-Gela road. The paratroopers made several sorties on German troops moving south toward Gela. Finally, the German movement changed and started back northward. A

Page 13

German battalion stopped along the road for a break and was ambushed, suffering heavy losses. These troopers held their position continuously, inflicting heavy losses on the enemy until relieved by other elements of the 505th CT and the 16th Infantry, 1st Division, on D plus 3. Lieutenant Watts and Lieutenant Ferrell, both gallant young paratroopers, were later killed near Venafro, Italy. Farther south, Lieutenant Colonel Arthur Gorham, with elements of the 1st Battalion of the 505th, succeeded in blocking all German movement southward toward the "Y" and finally captured and occupied the "Y" itself. When the 1st Division resumed the attack northward, this battalion worked with it. The bulk of the 1st Battalion was dropped near Noto, on the east coast of the island, where it captured the town and fought with the British Eighth Army for several days.

The 3rd Battalion of the 505th landed Company I exactly on its drop zone. This company had the mission of establishing patrol and radio contact with the assault elements of the 16th Infantry. It was also to light a large bonfire at one end of the lake as a signal for the amphibious troops. The house and haystack were set afire by Lieutenant Clark, 2nd Platoon, Company I, as the signal. The leader of the 3rd Platoon, Lieutenant Vandevegt, reached the railroad at 0230. He placed demolitions as planned and shortly after daylight contacted the advance elements of the 16th Infantry.

The Italian resistance was intense, but spotty and short. Company G of the 3rd Battalion dropped several miles east of its drop zone, near the highway crossing over the Acate River. It attacked and destroyed the Italian force guarding the crossing. It set up an all-around defense in this vicinity, patrolled vigorously and, all in all, turned in a fine performance. It was commanded by Captain James McGinity, later killed leading his battalion in Normandy.

The remainder of the 3rd Battalion was dropped southeast of the Acate River. It was picked up by the combat team commander [Gavin] on D plus 1 and participated in the fight on Biazzo Ridge.

The 2nd Battalion of the 505th was dropped as a unit east of S. Croce Camerina. Many of these troops landed on or near pill-

Page 14

boxes and in well-organized defensive areas. Despite its initial difficulties, the battalion was completely assembled by daylight, and under the leadership of Major Mark Alexander, attacked and captured S. Croce Camerina. It then cleaned up road blocks and pillboxes toward the beaches and toward Vittoria and Comiso. Many of these pillboxes were formidable affairs, some being three stories high with basements. By dark, on D-Day they had the area in front of the 45th Division completely under control. One group of paratroopers fought into Ragusa where they later joined Canadian troops of the Eighth Army. Another group fought into Vittoria.

The 456th Parachute Field Artillery Battalion, although initially widely scattered, reorganized promptly and engaged the enemy wherever he could be found. Several sections of the battalion participated in the fight at Biazzo Ridge. The remainder fought with the 2nd Battalion of the 505th and joined the fight at Biazzo Ridge late on the day of D plus--1.

In the final analysis and evaluation of the merits and accomplishments of the D minus 1 and D-Day airborne assaults, it is interesting to note that although only about one-eighth of the force originally planned to land in front of the 1st Division actually landed there, most of the missions assigned to the combat team were accomplished. Only at Niscemi, was the block thrown in front of the German reserves not fully effective. In front of the 45th Division, a thorough and efficient job of neutralizing the enemy's defenses was accomplished. This was not according to plan. It had been considered in the preliminary planning but was thought to be too much for one combat team.

On the night of D plus 1, the 504th Parachute Infantry (minus the 3rd Battalion), took off from North Africa to jump on the Farello airstrip, midway between Gela and the "Y", to reinforce the 505th. This regiment was engaged in flight by gunfire from, our own surface ships and friendly ground troops. Heavy casualties were inflicted and 23 transports [506 men] lost. The regiment, however, was assembled on the twelfth and soon joined the 505th CT. Together they fought with the 82nd Airborne Division, participating

Page 15

in several weeks of hard fighting culminating in the capture of the city of Trapani and of Cape Vito, the northwestern extremity of the island.

It is of tactical interest to note that the German forces near Catania were also reinforced by the German 1st Parachute Division. Later in September, similar tactics were used when the 82nd jumped into the Salerno beachhead on the nights of D plus 4 and 5, to reinforce the hard-pressed assault units of the Fifth Army.

It is probably because of the wide dispersion of the units in the Sicilian drop (some with the British, some with the Canadians, and others with the U. S. 1st and 45th Divisions) that the general public looks upon the Sicilian operation as a badly dispersed and ineffective effort. About D plus 5, I heard someone say that it was "probably the best executed Snafu in the history of military operations". I believe it could better be termed a "Safu." A "Safu" is a "Self-Adjusting Foul Up." But in the last analysis, the real worth of the airborne phase of the Battle of Sicily can best be gauged by an enemy evaluation of it. Speaking of it to an interrogator in a British prisoner-of-war camp in October 1945, General Karl Student said:

The Allied airborne operation in Sicily was decisive despite widely scattered drops, which must be expected in a night landing. It is my opinion that if it had not been for the Allied airborne forces blocking the Hermann Goering Armored Division from reaching the beachhead, that division would have driven the initial seaborne forces back into the sea. I attribute the entire success of the Allied Sicilian operation to the delaying of German reserves until sufficient forces had been landed by sea to resist the counterattacks by our defending forces (the strength of which had been held in mobile reserve).

General Student should have known an effective airborne operation when he saw one. He was the foremost authority in the German Army on airborne operations and he commanded the German airborne operation on Crete. In addition, he was Chief of Staff of all German paratroops from 1943 until his capture by Allied forces after the German collapse.

Page 17

Little things going wrong can cause a great deal of confusion in combat, and a certain amount must be accepted as normal, but if "little things" go wrong in an airborne operation, you really have confusion.

The pay-off then is in the individual troopers and the small-unit commanders. If they have learned their missions and those of other units working with them and if they have the initiative and moral and physical courage to do something about it, everything will turn out all right.

The Sicilian operation is a splendid example of this. In the last analysis, the accomplishment of the missions is a tribute to the courage and skill of the pilots and crews of the 52nd Troop Carrier Wing, who flew them in, and the fighting heart, individual skill, courage and initiative of the American Paratrooper. Here, in Sicily, he proved the hard way that vertical envelopment at night was feasible and almost impossible to stop, that the American trooper has the mental and physical courage to try anything, asking and expecting no odds. For as the dispersal was widespread, so also were the surprise and confusion of the enemy. Everywhere the Germans and Italians saw small groups of troopers coming out of the night. The panic of not knowing how many were coming or from where had its demoralizing psychological effect. In addition, their accomplishments in ground fighting were an immeasurable contribution to the successful Sicilian campaign.

Perhaps the German high command should have heeded the opinions of General Student. Surely he knew, and it may well have known, that Salerno, Normandy, Holland and Wesel were all practicable within the foreseeable future.

CHAPTER 2: Plans and Operations in the Mediterranean

SICILY WAS A SOBERING EXPERIMENT for all of the troopers and staffs of the U.S. 82nd Airborne Division. But from it men and officers acquired new and more practical ideas about what they should carry into parachute combat. It was decided after the heavy loss of equipment containers in the Sicily operations that more weapons would have to be jumped on the person so that they would be immediately available. In particular the troopers would jump with more grenades and less food.

Another important change was the substitution of simple passwords for mechanical aids in night challenging.

From here on out the troopers of the 82nd Airborne knew what it meant to leap from the door of a plane into the inky black night. They knew full well that whether they lived or died depended entirely upon their mental and physical resources and what they carried out the door with them. Only God came along with you was the feeling after Sicily.

There had, of course, been far too much dispersal over Sicily.

In the next the staffs of all echelons were determined to obtain better massing and more accurate delivery. At this time, too, pathfinding was initiated and teams were trained to go ahead of the troop transports, jump, and set up radar and visual signals accurately in the drop zones to guide the transports in. New and more practical means of effecting a rapid assembly were improvised. Arrangements were also made to have the assault paratroop waves accompanied by more effective antitank means (glider-borne 57mm guns if possible). And many other innovations were designed to add to the striking and holding power of the next paratroop force to go in, wherever it would be.

Right after the Battle of Sicily the 82nd Division returned to North Africa, arriving there on August 20, 1943. There it received reinforcements and equipped and prepared itself for the coming invasion of Italy. For the Division Commander, Major General Matt Ridgway, and for the staffs of the division, this was an extremely busy period. Plans were made, and then there were

Page 18

changes, and more plans and changes. Yet all of that was typical of what usually happens in the planning stages of an airborne operation.

The student of future airborne operations has to realize how normal these shifts and changes are for any airborne operation that has to be planned and staged in a short period of time. And he must realize clearly how many planning details must be attended to, and checked and rechecked. There must be full coordination with the amphibious troops and with the naval and air forces. Coordination for bombing and fighter support is especially vital and air supply may be equally so. And very often there must also be a careful coordination with the activities of the State Department. All these agencies can be expected-in fact, you can depend on it-to make numerous changes in their own plans, but from the whole must emerge a cohesive, workable, well thought-out, operational airborne scheme.

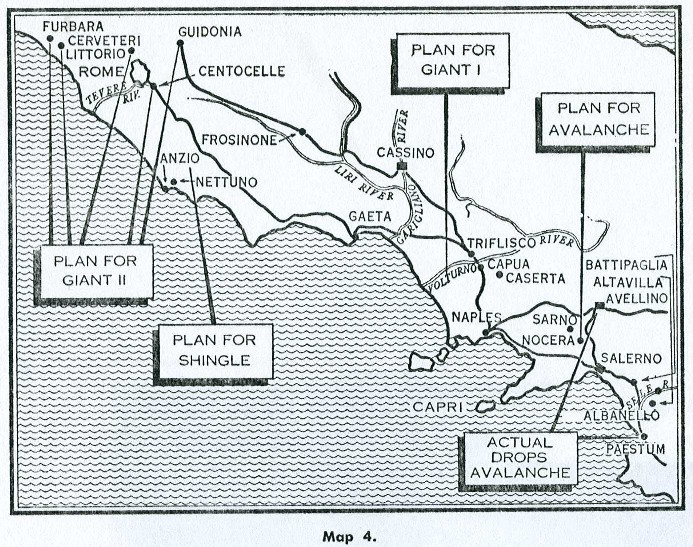

The final plan for the amphibious invasion of Italy contained the following major elements (see Map 4):

(1) the main assault by the U.S. Fifth Army with the mission of capturing Naples;

(2) two attacks by the British Eighth Army, one against Calabria and another against Taranto;

(3) a naval diversionary attack in the Gulf of Gaeta. This was to be known as operation AVALANCHE;

named, one can suppose, for the avalanche of combat troops soon to swarm onto the war-weary Italian Peninsula. But to some of the wags on the staffs of the 82nd Airborne Division the name was more indicative of the avalanche of airborne plans and papers that engulfed them in the days that soon followed.

To carry out its mission, the Fifth Army planned to invade Italy at the Gulf of Salerno, fight northwestward, capture Naples, and continue the fight northward until all of Italy was overrun. The 82nd Airborne Division was made available to the commander of the Fifth Army, General Mark Clark, for this operation. How best to make use of the division now became a problem of much concern and speculation. The first mission presented to the 82nd called for the seizure by an airborne task force of the towns of Nocera and Sarno at the

Map 4.

exits to the passes leading northwest from Salerno. The purpose was to cover the debouchment of the Fifth Army from the Salerno area. All available transport planes and gliders, 318 of each, were to be used on the operation. The division commander gave missions to the regimental commanders at the division command post at Trapani, Sicily, about August 1.

The staffs made hurried studies to select drop zones for the parachutists and landing zones for the gliders. Our airborne assault was to be supported by an amphibious assault by troops from the infantry division landing in the Amalii-Maiori area on the Sorrento Peninsula. After considerable study in conjunction with the Air Forces, of the terrain, ack-ack, and possible flight routes, it was decided that the paratroopers of the 82nd would have to be dropped along Sorrento Ridge at altitudes from 4, 500 to 6, 000 feet, in moonlight. The airborne operation was also planned at extreme fighter range, and this, coupled with the ground conditions, the ack-ack, and the possibilities of hostile fighter interception, as well as the real vulnerability of the C-47s to any kind

Page 20

of an attack, ruled out anything but a night airborne show. Fighter range and support are critical factors in any airborne plan.

It was decided, however, on August 12 to throw this whole plan out and use the 82nd Airborne farther inland. On thinking back now to the situation at the time, it seems to me that this first plan contemplated the use of our airborne units merely to gain a temporary tactical advantage. Their use in the manner planned would hardly have had a decisive bearing on the outcome of the operation as a whole. It was a good thing that the decision was made to drop the plan.

On August 18, General Ridgway was told that a new decision had been reached to conduct an airborne operation on the Voltumo River, northwest of Naples and some forty miles from the nearest beach landings in Salerno. Initially, this new plan gave the 82nd Airborne Division the mission of destroying all crossings of the Volturno from Triflisco to the sea and of holding the Volturno itself against all enemy attempts to cross. The airborne force was to be given immediate support by an amphibious assault against beaches just to the south of the mouth of the Volturno, and contact between the 82nd and the nearest unit landing at Salerno, the British 46th Division, was to be expected, at the latest, in five days. I was designated as the airborne task force commander.

Staff planning for the new operation, known as GIANT I, was undertaken without delay at all staff levels concerned. But shortly the Navy announced that the beaches selected for the amphibious assault were unsuitable so this phase was dropped from the plan. Without this landing of a force from the sea to back up our airborne task force, the problem of resupply for the airborne forces now became a most critical factor. Our assault force was to be a task force of two regiments of parachute infantry, a battalion of parachute field artillery, two companies of parachute engineers, and two batteries of 57mm antitank guns, and medics, signal, and reconnaissance units to balance the force. To keep this force able to operate continuously, we would need a daily tonnage of supplies of all classes amounting to 175 tons. This minimum of food and ammunition had to be delivered to us in one way or

Page 22

another, for an airborne force is, like any other, dependent on supplies, and usually more so because it operates completely within the enemy's area. When the situation gets tight such a force can only keep on fighting. It cannot fall back toward a supply base.

Obviously, this would require considerable airlift. And it would equally require an almost incredible amount of good luck and good planning to deliver the needed supplies to each unit of the task force at the times and places required in the face of hostile interference and the many circumstances of combat that can cause the best of plans to go awry.

At the very least, the airborne task force would need regular supplies for a period of five days-until contact was made between our force and units of the British 46th Division which would have landed at Salerno. There was some chance, as well, that the progress of these other forces would be slower than expected, and in that event we would need steady resupply for many days. Intact, had the operation been carried out as planned, it is probable that we would have been on our own for a whole month.

Any serious failure in the resupply of the 82nd Airborne Division task force could only mean its loss. This is true of any airborne force that drops into territory strongly held by an alert and able enemy. No surrounded force can hold out long without food, and when the ammunition is gone the situation naturally becomes hopeless. The planning for the airborne operation was carried through in the smallest detail. General Ridgway emphatically presented the resupply problem to the Fifth Army staff. Approximately three groups of troop carrier transports, about 145 ships in all, would be needed to bring in our daily re-supply by parachute. Because of the great likelihood of interception by hostile fighters, the supplies would have to be delivered at night, on a time schedule that was changed daily. Each day a fast observation ship would fly over our operational area on a prearranged schedule to confirm the daily delivery plan by panel and smoke signals.

One novel twist was given to the planning when it was realized that there were several thousand Allied prisoners of war in the area between Capua and Caserta. Resupply for these prisoners ap-

Page 23

peared to be a necessity, and just what we should do with them in the event of their liberation was a difficult problem. It was also of highest interest to the troopers of the 82nd that the rear echelons of the German 1st Parachute Division and the Hermann Goering Panzer Division were bivouacked near our proposed area of operations. Word was going the rounds that if the Hermann Goering outfit had anything left after Sicily they were about to lose it now. And every man was curious about the 1st Parachute Division and extra willing to tie into them.

As task force commander, I visited the command post of Major General Hawksworth, commanding the British 46th Division, at Bizerte in late August. I arranged for delivery of American-type ammunition and evacuation of our wounded, and for an exchange of information on day and night visual recognition signals, radio frequencies and vehicular markings. General Hawksworth estimated then that he would contact the airborne troops in four to five days at the most. Concurrently with all of this the 82nd Airborne Division was directed to be prepared to drop a separate parachute battalion on either Battipaglia, Avellino, Nocera, or Sarno, for the purpose of blocking movement through those localities. The 2nd Battalion, 509th Parachute Infantry, was attached to the division. This was the battalion that had jumped in North Africa after a 1500-mile flight from England in November 1942.

A final briefing for all higher commanders was held at the Fifth Army forward command post on August 26. Each commander in turn outlined his plan to carry out the mission assigned him by the Commanding General of the Fifth Army.

The destruction of all crossings over the Volturno from above Capua to the sea and the denial of all Volturno crossing sites to the Germans was a satisfying, if not most pleasant, mission to study and prepare for. But the job proved much more difficult of realization on analysis than the higher staffs had first thought. It was the daily air resupply of 175 tons which proved to be the obstacle that couldn't quite be overcome. At least it couldn't be overcome unless the North African Air Force was willing to take an

Page 24

almost certain daily loss of transports or bombers, whichever would be used. There was an extensive bombing program already under way. The big ships of the North African Air Force were working over the boot of Italy from top to toe. The Air Force had already carried out its costly, long-distance raid from bases in Libya on the Ploesti oil fields in Rumania. As for the ships of the Troop Carrier Command, they would be operating beyond fighter support, which certainly made it look like a heavy loss of transport planes to keep our task force going.

Still in the minds of all of the pilots was the recent interception of a German air transport column on the way to North Africa with badly needed supplies for the beleaguered troops of Von Arnin. Seventy-five transports were shot down in not many more seconds.

Rommel's Afrika Corps was starved into submission by German supply ships being sunk by combined Allied naval and air actions. They tried air resupply with slow JU-52s and Me-323 transports.

Corey Jordan writes in his online book,

SIDEBAR: Transports without Air Superiority

http://home.att.net/~C.C.Jordan/P-38MTO.html

By late winter, the Luftwaffe was flying as many as 100 transport sorties across the Straits of Sicily to re-supply the exhausted Afrika Korps, who had been squeezed into Tunisia by U.S. forces from the west and the British 8th Army from the east and south. Generally flying at altitudes below 100 feet, these transports were usually escorted by Bf-109 and Fw-190 fighters. Allied fighters were deployed to intercept these transports, the North African Air Force P-38's being cut loose to hunt down the Luftwaffe.

On April 5th, twenty-six P-38's intercepted a huge formation of German transports and their escort. 16 of the German aircraft went down, including two of the escorts. A pair of P-38's were lost, with one pilot missing in action. Elsewhere, P-38's accounted for another 15 German fighters. Combined efforts of NAAF fighters and bombers destroyed up to 200 x Luftwaffe aircraft on April 5th,with many destroyed on their airfields. Just 5 days later, on April 10th, the P-38's destroyed another twenty German transports and 8 escorting German and Italian fighters. Later that afternoon, B-25 Mitchell medium bombers and their escort splashed 21 more transports and four of the escorting fighters. Despite these serious losses, the Luftwaffe continued to fly these aerial "convoys". On April 11th, the Lightnings located and destroyed another twenty six Ju-52 transports and 5 x Bf-109 fighters did not return to their airfields that evening. The Luftwaffe was being bled white. Finally, the German re-supply effort came to a halt when an entire convoy of the massive Me-323 Gigant six-engine transports was shot down by a combined force of Spitfires and South African P-40 Kittyhawks.

The Allies had achieved air superiority by April 22nd. There remained some Luftwaffe aircraft in Tunisia, however, they were soon destroyed or evacuated to Sicily. On May 13th, 1943, the last of the Deutsches Afrika Korps surrendered to the Allies, having fired off all their remaining ammunition and destroying any usable equipment. About 240,000 Germans and Italians went into captivity. The focus of all now turned to Sicily. The Germans understood that this would be the next target of an Allied invasion. The question was, what could the Luftwaffe do to defend the island?

Air Marshal Tedder and General Clark decided in the end that the possible gain from our Volturno mission would not be worth the probable losses. The mission was called off, and thus ended GIANT 1.

Thirteen days remained until D-Day. General Ridgway and the staff of the 82nd Airborne Division returned to the headquarters of the division at Kairouan in North Africa, where preparations were continuing for any type of airborne mission that might fall to the division's lot.

On the evening of September 2, the division commander and several staff officers were called to the Headquarters 15th Army Group at Siracusa, Sicily, to receive the first information of a new mission. The new job was to be the seizure of Rome, one of the most interesting airborne plans of the war, and a plan that will be discussed pro and con for many years to come. This operation was known as GIANT II and called for placing the strongest airborne task force the available aircraft could carry on and near three airfields immediately east and northeast of Rome. Because of the range there was no possibility of fighter support. The date for, GIANT II was the night of September 8-9. The mission was to secure Rome by operating in conjunction with Italian forces in the Rome area. The airborne lift was to be repeated, the next night

Page 25

and as directed thereafter, until the mission of the 15th Army Group was accomplished. The airborne part of the operation was to be supported by a landing at the mouth of the Tiber River also staged by troops of the 82nd Airborne Division.

This mission posed some new and extremely interesting airborne problems. Again the operation was beyond friendly fighter range, and since enemy fighters were very active, the operation was limited to hours of darkness. The simplest method of delivering the troops was to air-land them on the airfields with the cooperation of the Italians. But since our transports were not to enter the enemy fighter range until after dark and they had to clear by daylight, rigid limitations had to be placed on the time that could be spent on the Rome airfields. Parachute troops of course require no landing time whatever; a completely equipped fighting force is dropped while the ships remain in flight. Airlanding C-47 transports on a one-strip airfield with a control officer on the field from the landing troop carrier unit can rarely be done at a faster rate than thirty-six transports an hour. That rate has been exceeded, but not under combat conditions. This means that at best a battalion of infantry [792 men] an hour per available airfield is all that could be landed. And for practical planning purposes, this is a pretty optimistic expectation.

Under the conditions existing in the Rome area and the time limitations these conditions imposed upon us, the forces that could be air-landed in a single night would be relatively small.

The airfields were small ones without runways. Effective cooperation of the Italian ground forces was especially doubtful.

We might well find units of the German Wehrmacht at or near the fields. There was no assurance of an efficient handling of aircraft damaged in landing and it was not clear how traffic in and over the fields was to be controlled.

The Rome area was beyond glider range from the take-off airfields in Sicily. It had to be accepted that the success of the mission was wholly contingent on such full cooperation from the Italian military forces as would insure the neutralization of German antiaircraft defenses along the planned flight route, the security of the

Page 26

landing fields or drop zones to be used, and the furnishing of essential supplies, and in addition full military cooperation of all Italian forces against German troops. This made quite a bill of goods.

Nevertheless the planning moved at a rapid pace and the afternoon of September 8 found the troops of the 82nd busily checking orders and plans, loading the para-containers, and making a last check on rations, ammo, and weapons.

The greatest difficulty was the lack of assurance from the Italian government that the airfields around Rome would be freed of Wehrmacht and German ack-ack troops. The flak we would run into on the way from Sicily to Rome was sure to be heavy, and losses from it likewise unless it were taken out beforehand. Of equal concern to the 82nd Airborne Division was the reception to be expected on the airfields. It was necessary not only to clear these fields of the enemy, but to have guides and interpreters, ammunition and food supplies, and vehicles ready for our use at the fields when we landed. There must also be further advance organization by the Italian Army for the control of traffic around the airfields, clear the airfields of our damaged and cracked-up planes, and for security against attack on the fields by German or hostile Italian forces.

The agreement reached between Allied authorities and the Italians at Siracusa provided for all of this. There were, in fact, several pages of itemized needs including such things as telephones, picks, shovels, wire, gasoline, and civilian laborers, all of which were to be furnished by the Italian commander to the airborne troops. The Italians had also agreed to clear the Tiber River so that there could be amphibious support for the airborne landl11gs.

But I think the fact is that the Italians at Siracusa had simply promised everything-about ten times as much as they could possibly have done. And it became fully evident that there were no guarantees of the needed support at the airfields where the regiments of the 82nd were to land, so the plans were changed almost at the last minute.

Page 27

The leading assault regiment, the 504th Parachute Infantry, was to land on the Furbara and Cerveteri airfields near the seacoast. From there they were to push inland towards Rome. The regiment jumped on the second night, the 505th Parachute Infantry, would land on Guidonia, Littorio, and Centocelle airfields, all of which are considerably nearer the center of the city of Rome.

Since the Sicily operation, we had paid a great deal of attention to pathfinders as means of having parachute transports home on the proper drop zones. For the Rome attack, pathfinder ships and men would precede the main landings of the 82nd and bring them accurately in. The pathfinder ships and personnel were based on the field at Agrigento, Sicily. On the evening of September 8, these ships were fully loaded, warmed up, and ready to take off. But minutes before the take-off, word came from higher authority that the mission had been postponed for twenty-four hours.

Brigadier General Maxwell D. Taylor, chief of artillery of the 82nd Airborne Division, had been sent through to Rome twenty four hours earlier to confer with the leading Italian authorities.

He was to inform the Allied commander by code whether or not in his opinion the operation should be attempted. General Taylor and a small staff were taken to the island of Ustica by a British PT boat where they were transferred to an Italian corvette which landed them at Gaeta, the scene of much bitter fighting later in the war. They were quickly taken from Gaeta to Rome where they conferred with General Carboni, commanding the Italian troops in the Rome area, and the aging Marshal Badoglio. The Marshal and General Carboni both agreed that in recent days the German forces in Italy had been greatly increased in strength. They said further that the Italian troops had little or no gasoline and only enough ammunition for a few hours of fighting, that they could not guarantee that airfields would be in Italian hands, and that, anyway, our airborne landings would cause the Germans to take drastic steps against the Italians and that therefore the whole plan as proposed would be nothing less than disastrous.

General Taylor decided they were right and radioed the pre-

Page 28

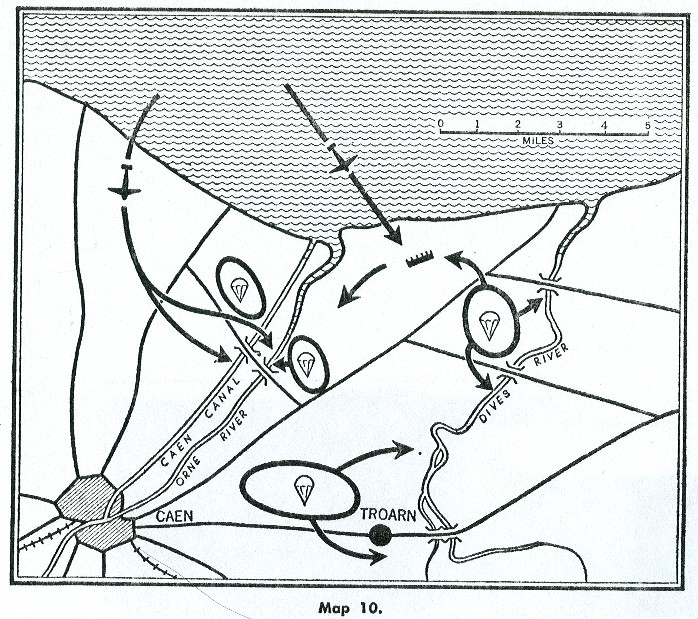

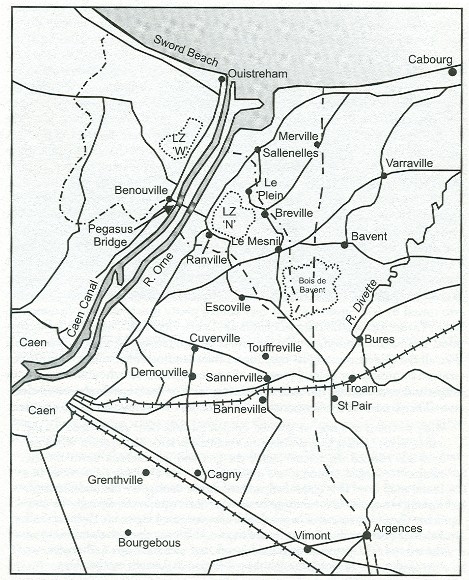

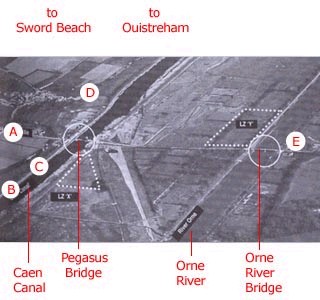

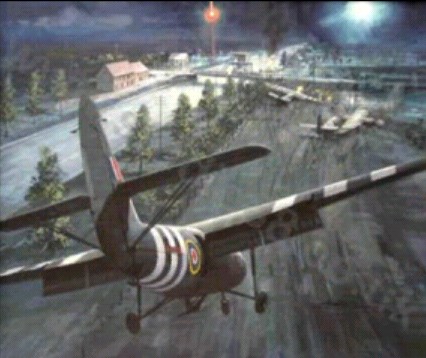

arranged code message, and the operation was called off. D-Day came and H-hour struck, and despite the many plans and the days and nights of staff work, the airborne troops found themselves sitting and waiting on their take-off airdromes. Patience is an essential attribute of a good airborne trooper.