RETURN OF THE "STEALTH" GLIDER

Fortress Eban Emael. 1940.

This impregnable fortress blocks Germany from driving through Belgium like it did in World War I. Formed of huge gun positions with massive thick concrete walls. It would take at least a division to seize, but in the early dawn while the Belgium defenders looked out horizontally, German Fallschirmjaegers(Paratroopers) and gliders did the impossible. A group of less than 100 men land directly on top of the fortress, skidding to a sudden stop. These men jump out of their gliders and with special shaped-charged explosives seized the fortress which is captured for advancing German Forces.

The Orne River Canal bridges. 1944. D-Day.

www.youtube.com/v/3R9wixc0LKs

www.youtube.com/v/3R9wixc0LKs

Approaching the bridge, the night before D-Day are British Paratroopers in Horsa Gliders, these gliders land at both sides of the bridge. A desperate struggle between elements of the British 6th Airborne division and the German 716st and 21st Panzer Divisions for the vital strategic bridge over the Canal De Caen in Normandy, midway between the villages of Benouville and Le Port, during the night and day of 6th June 1944. The battle commences at 0016 with the daring glider borne coup de main assault on the bridge by "D" company 2nd Ox & Bucks Light Infantry, led by Major John Howard. They kill the the guards and take the bridges. These British 6th Airborne Division Paratroopers hold these positions and the left flank of the entire D-Day invasion---resulting in the bridge being renamed; "Pegasus Bridge".

The mighty Rhine River. 1945.

On the morning of March 24, 1945, an enormous air armada crossed the Rhein River near Wesel in western Germany. The column, two-and-a-half hours long, consisted of more than 1,500 IX Troop Carrier Command airplanes and gliders. To their left were about 1,200 RAF airplanes and gliders. The entire assemblage was supported by 880 U.S. and RAF fighters. This was Operation VARSITY, the Airborne support for the U.S. Ninth and British Second Armies' crossing of the Rhein.

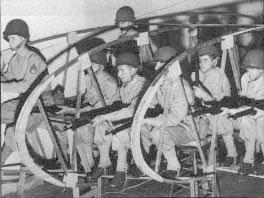

Varsity was unique not only in magnitude. Three weeks before D-Day, Maj. Gen. William M. Miley, commander of the Army's 17th Airborne Division, briefed the glider operations officers of the 53rd Troop Carrier Wing's five groups on the impending operation. His 194th Glider Infantry Regiment needed one more infantry company to carry out its assignment. He asked for one of the troop carrier groups to provide that company, to be made up of glider pilots after they had landed in their designated zones. It would be an all-officer company, maybe the first in the history of modern warfare. Capt. Charles O. Gordon, glider operations officer of the 435th Troop Carrier Group, accepted this unusual assignment. He was to become commander of the provisional company. Personnel of the 194th Regiment trained his glider pilots for two weeks in infantry tactics and weapons.

The vast majority of the glider pilots were second lieutenants or flight officers. None had ever expected to serve as infantry, but they accepted that duty enthusiastically. These men were organized into four platoons, one for each of the group's squadrons. Most squad leaders were second lieutenants. They were to assist the 17th Airborne Division in securing a designated area northeast of Wesel, establish roadblocks, and make contact with British forces northeast of the town. For the first time, each of the 435th's C-47s would be towing two gliders; and, for the first time, their landing zones would not have been secured by Paratroopers.

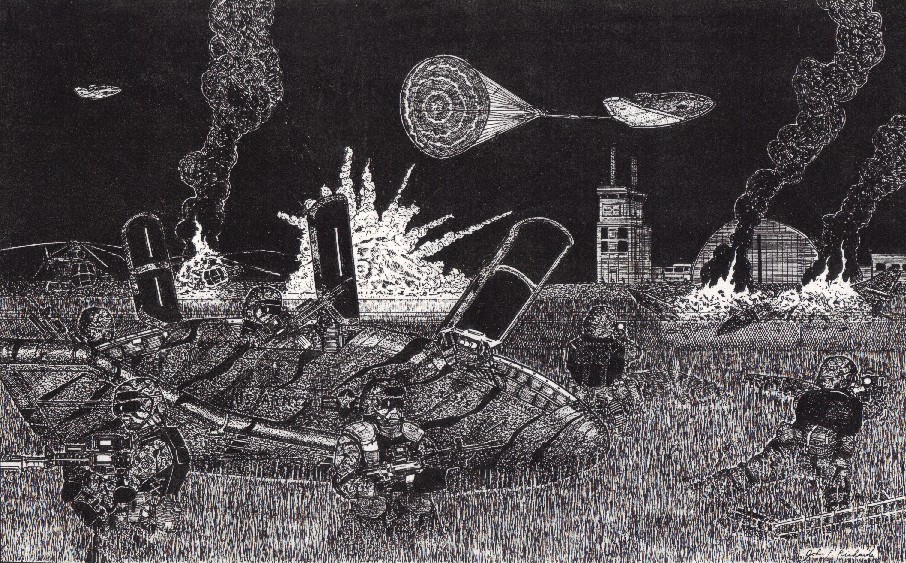

When the 435th's 144 gliders, loaded with airborne infantry and equipment, cut loose over the landing area, they came under heavy ground fire with substantial casualties among the infantry and glider crews. Once on the ground, they continued to be hit by sniper and mortar fire that had to be subdued before they could move to their assigned area of two crossroads--one that would earn the name "Burp Gun Corner." There they cleared several houses, taking a large number of prisoners before digging in for the night.

Several times, small groups of German Soldiers attempted to infiltrate their defensive positions but were driven off in a series of firefights. The defenders knew that German troops, retreating ahead of British forces, would attempt to overrun their position, probably supported by armor and mobile guns. The ground held by the glider pilots was at the top of a ridge, the country sloping away toward Wesel, the direction from which an enemy attack would come. The reverse slope would allow enemy forces to advance almost to the 435th's area before coming under fire.

About midnight, the first attack by a German tank, supported by a large number of infantry, hit the crossroad defended by the 75th Platoon. They came under heavy fire and retreated. Thirty minutes later, a German tank and approximately 200 German infantry, supported by two 20mm flak guns, attacked the position defended by the 77th Platoon. As soon as the enemy troops were in close range, the glider pilots of that platoon, where the attack was concentrated, opened fire. Small-arms fire took a heavy toll on enemy infantry during the hour-long battle.

Flight Officers Chester Deshurley and Albert Hurley held their positions, firing their machine guns until the tank came within fifteen yards of them, as did Flight Officer Robert Campbell, armed with a tommy gun [Thompson SMG]. At that point, Flight Officer Elbert Jella severely damaged the tank with his bazooka. The retreating tank ran over one of its flak guns; the other was captured by the glider pilots.

At daybreak, the glider pilots defeated several smaller attacks and joined up with British forces coming out of Wesel. Their job was done with the professionalism of veteran infantry troops. They soon were relieved from further duty as ground Soldiers. Overall, they suffered 31 casualties in the operation, killed a large number of enemy troops, and captured several hundred prisoners.

"The Battle of Burp Gun Corner," a unique event in Air Force history, was covered by Stars and Stripes but then slipped into obscurity. In March 1995, Air Force Chief of Staff Gen. Ronald R. Fogleman learned from retired Maj. Charles Gordon of the heroic actions of these glider pilots turned infantry and directed that appropriate awards be made to those who took part in the fighting. At the 435th Troop Carrier Reunion in October 1995, Flight Officers Jella, Deshurley, Campbell, and Hurley each were awarded the Silver Star. All others who fought in the battle were awarded the Bronze Star, but many of those more than 280 men had died before their heroism was recognized.

The Glider.

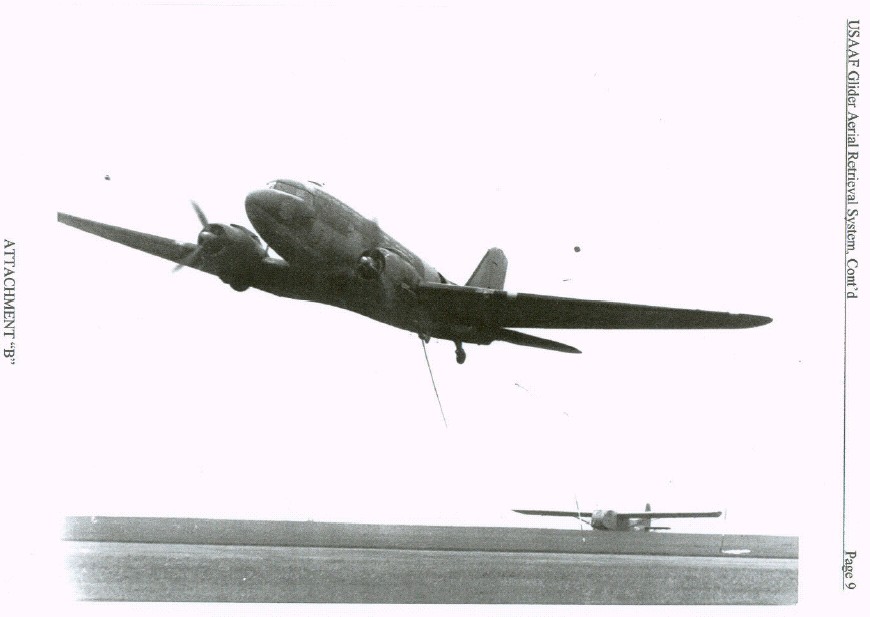

Most of us think of gliders being towed by C-47 "Gooney Birds" watching the film A Bridge Too Far or The Longest Day. In Operation Burma, a glider is "snatched" from the ground by a low-flying C-47 and towed back to base. In these films, the glider is shown to be a stunning success. You then may ask why we are not using gliders today?

When Hitler needed them, they were ready. So it was that at dawn on May 10, 1940 nine gliders containing 78 German Paratroopers landed on the grassed-over roof of a massive fort at Eben Emael on the Belgian border. The surprise attack was a complete success. Anti-aircraft gunners were quickly overpowered, the gun emplacements were blown up, and within hours the 850 or so defenders, prisoners in their own fort, had surrendered.

www.youtube.com/user/2bn442RCT#grid/user/C506D01BF22C00AB

www.youtube.com/user/2bn442RCT#grid/user/C506D01BF22C00AB

Impressed by this stunning success, the Japanese and British began their own glider programs. But it was not until almost a year had passed, by which time it had begun to seem more and more likely that America would become involved in the war, that Major General Henry "Hap" Arnold, chief of U.S. Army Air Force, gave the order to begin development of a glider that could carry troops and hardware and land behind enemy lines.

Any lingering doubts about the efficacy of gliders in war were dispelled by the German capture of Crete in early summer 1941. The island was taken from defending New Zealand troops by an entirely Airborne force which either dropped by parachute or landed in gliders. Ironically though, so many German troops were killed that Hitler swore never to use Airborne troops again. And so Germany's pioneering use of gliders ended just as the Allies' was beginning.

www.youtube.com/watch?v=5zo4PTMg9uA

www.youtube.com/watch?v=5zo4PTMg9uA

In America, the glider program began slowly but received a mighty boost after Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7. Arnold looked around for someone to run it, but there were no military personnel with any experience. And so he chose a civilian champion sports glider pilot, Major Lewis Barringer, whom he brought to Washington, D.C., and gave the rank of major. Soon thosands of glider pilots were trained and their contributions to Allied victory were immense. Gliders saved the day in numerous WWII battles, flying General Orde Wingate's Chindits hundreds of miles behind Japanese lines to flying in doctors to the 101st Airborne Division surrounded at Bostogne. Gerard Devlin's Silent Wings and Milton Dank's The Glider Gang vividly illustrate the epic heroism of our glider troops, who upon landing fought as Airborne infantry. Truly, our glider pilots were the "Forgotten Heroes" of WWII, but this is going to change as you will soon see, as they were just a little bit ahead of their time for technology to fully exploit the military potential of the glider.

When you study the history of the glider in World War II, you will see the basic purpose of the glider was to either seize objectives by stealth (Coup de main: the top two examples) or to deliver jeeps, light tanks, artillery pieces and heavy supplies that parachutes couldn't deliver at that time (Air-delivered logistics). However, these gliders had to be towed by another airplane very close to the targets and then cut free. This is where all the problems come from. Tow ropes would break. Gliders would get tangled up with the tow aircraft. The entire procedure was very tricky.

A Retired USAF LTC "Oregon" Jerry Baird USAF with an awesome career flying everything from gliders to jet transports writes:

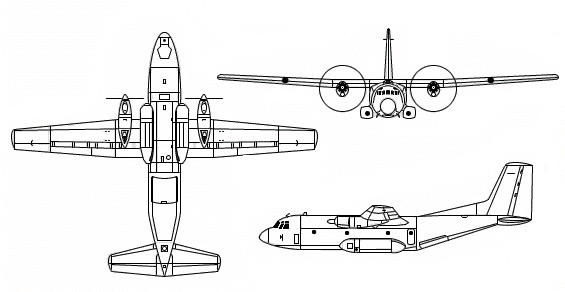

The original C-123 concept was derived from the YG-18 and was designated YG-20, as I recall. That glider would have been able to carry 10,000 - 16 000 lbs of cargo/pax. It would have been all weather with retractable gear and flaps, elec actuated and a 24 volt system with a put-put. It could be deiced in flight.

The helicopter signaled its death kneel. Could the need for silent insertion resurrect the glider?

Is it feasible? Could it be towed and snatched by a C-130?

I flew the CG-15A into the DZs of FT Bragg and was snatched out by C-47 several times."

"In addition to silence, the glider has the advantage of a portion of a platoon already grouped and ready to fight as you well know. Four gliders landing together and you can have the makings of a small company. If you are devoted to the three concept, six gliders and you can have three platoons and a nearly full company.

The LTC is right. We need gliders today and they can be made to work better than ever before. The C-123 as a powered aircraft served throughout the Vietnam war and is showcased in the films, Air America and Con-Air

The U.S. Army's Mistake that Will Not Go Away: Has Light Tanks--But Often Refuses to Fly Them to Win Battles by Decisive Firepower & Maneuver

Persistent research into the history of the U.S. Army's misuse of its light tracked tanks continues to reveal new discoveries and horrors; a mistake that refuses to go away.

Battle losses in places like Task Force Smith, South Korea, Mogadishu, Somalia and Wanat, Afghanistan--where light tanks could have been brought to win the fight--but were not--have had no effect on successive generations of Army bureaucrats to fix our force structure.

Even battle victories where light tanks were taken to the fight--in places like the Pusan Perimeter and march to the Yalu river in Korea, Vietnam, Panama and mild successes like in Northern Iraq have also absurdly had no effect on Army bureaucrats and force structure! Since objective reality--negative (-) or positive (+) --has no effect on successive generations of Army bureaucrats--as well as the rank & file, it's clear the problem is a subjective one that keeps being perpetuated in the Army bureaucracy and non-professional culture. This essay will ascertain the blame and propose the needed corrections.

Prologue 1945: We Have Excellent Light Tanks

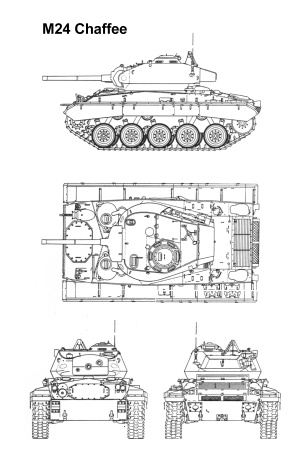

Our story begins with a generally-agreed by most experts as an EXCELLENT light tank, the 18.4 ton, steel M24 Chaffee

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/M24_Chaffee

...introduced in 1944 with the same 75mm gun as on the Sherman medium tank. M24s are still being used today by some of our allies some like Norway upgrade them (NM-116 variant) with safer M113 Gavin diesel engines and 90mm guns with better stabilized optics.

Unfortunately, the second generation of German medium, defensive tanks were impervious to front and side shots from not only the Sherman 75mm gun, but even our increasingly heavier and heavier 37mm and 57mm towed anti-tank guns--ever more difficult for the non-mechanized, walking infantry to man-handle. Recoilless rifles and rocket launchers "Bazookas" were embraced by the infantry as the short-range anti-tank, assault firepower "solution" at war's end. Yet 5 years later the 2.36" bazooka would fail miserably against Communist T34/85 medium tanks during the Task Force (TF) Smith debacle.

Note that the even superior, extremely fast 60 mph 17.7 ton M18 Hellcat light tank [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/M18_Hellcat] with a 76mm gun was highly successful killing all German tanks in WW2 and a 90mm gun-equipped Super Hellcat was available. The problem was they were in a sub-bureaucracy called "Tank Destroyers" that died when its patron, LTG McNair was killed in the botched Operation COBRA USAAF carpet-bombing in 1944--and was not around to stop the bureaucracy from disbanding them. With cavalry branch also disbanded the same year, the tank-dueling mentality in heavier and heavier tanks on the plains of Europe in main bodies clouded the minds of the new "Armor" branch.

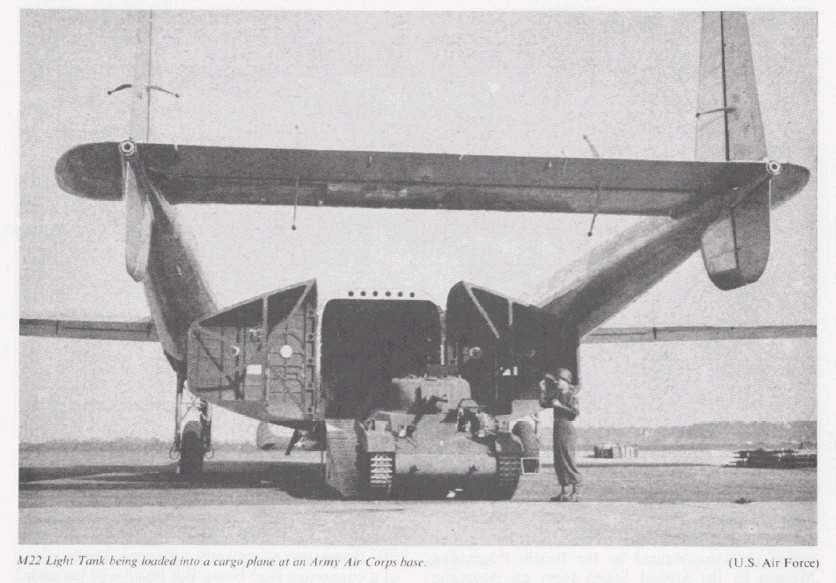

At war's end, a light tank company of M24s would be ASSIGNED to the infantry division manned by "tankers"--outsiders--easily ignored and not factored into tactics and combat plans. In short, the walking infantry refusing to light mechanize itself, didn't want to be bothered with operating its own towed AT guns or its own light tanks to combat enemy tanks and provide fire support. More important activities like continuing the pre-WW2 "From Here to Eternity" routine of slow dismounted infantry drills and after-hours carousing beckoned. While the Army Airborne Center and Ground Forces wanted to get light tanks to the fight--they didn't have any airplanes available from the new separate service bureaucracy U.S. Air Force that could lift them--and didn't think ahead to make sure the new Army CG-10A Trojan Horse glider was large enough to carry light tanks--like the British did with their Hamilcars to fly Tetrarch and our own M22 Locust 37mm gun light tanks into Normandy on D-Day and across the Rhine.

www.youtube.com/watch?v=vWjQ7yPJtaA

www.youtube.com/watch?v=vWjQ7yPJtaA

We know from Keith Flint's book, Airborne Armour that the mere sight of the little Tetrarch light tanks resulted in the Germans not counter-attacking the British 6th Airborne on June 7, 1944. Why the American Airborne did not use its own M22 Locust light tanks and bought some Hamilcar gliders to deliver them is a big question--in light of the Arnhem failure and heavy casualties throughout the war due to a lack of fire support from an armored platform that could wade into enemy machine gun fire and suppress/destroy them. You hear a lot of commentators TODAY complaining about the Tetrarch/Locust's 37mm guns not threatening German tanks, but when you read actual WW2 combat reports infantry loved using towed 37mm AT guns to bust pill boxes and dug-in enemy positions.

combatreform.org/Combat-Lessons-01-the-Rank-and-File-in-Combat-What-They-re-Doing-How-They-Do-It-1944.pdf

Thus, light tanks with 7.62mm medium machine guns and cannon shooting 37mm HE shells could have provided critical fire support that could not be deterred by enemy MG42 machine gun fire--which often suppressed and pinned-down our infantry:

combatreform.org/lightmachineguns.htm

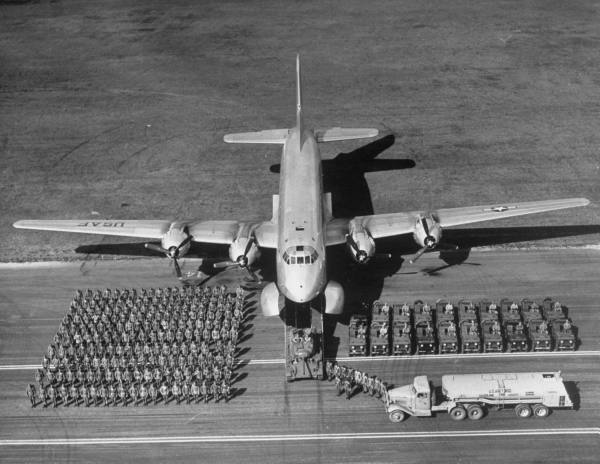

Hamilcar When CG-20 glider prototypes that could deliver light tanks became available--the Army Airborne did not take note of them. When C-82 transport became available, the Army didn't take advantage of them, either.

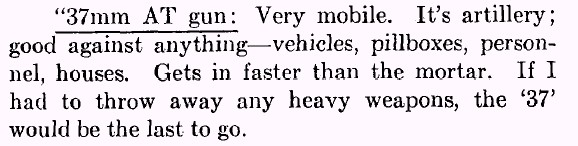

Army Considers M24 and M18 Light Tank Air Delivery--then Gets Lazy

combatreform.org/freedroplighttanks1.jpg

From AFV Weapons Profiles #46, Profile Publications, Windsor UK, 1972, Light Tanks M22 Locust and M24 Chaffee by Colonel Robert J. Icks, Page 100

As the quote above shows, both the M24 and the M18 could have been dismantled into (2) loads so (5) men could reassemble them in 3.5 hours. Is it just me, or do I detect that this IS NOT THAT HARD TO DO, so the Army saying "No" is pure lazy bullshit. Colonel Icks screws up his narrative on page 102 by whining that the somehow 3.5 hours of work was "impractical" and then whined that carrying M22 Locusts with turret removed and in a C-54 was bad because the delivery aircraft needed a runway to land on--forgetting the FIRST PICTURE IN HIS BOOK showing a M22 offloading from a C-82--that did not need smooth runways. Its the picture I have posted at the top of this essay. Icks' anti-Airborne prejudice clearly shows.

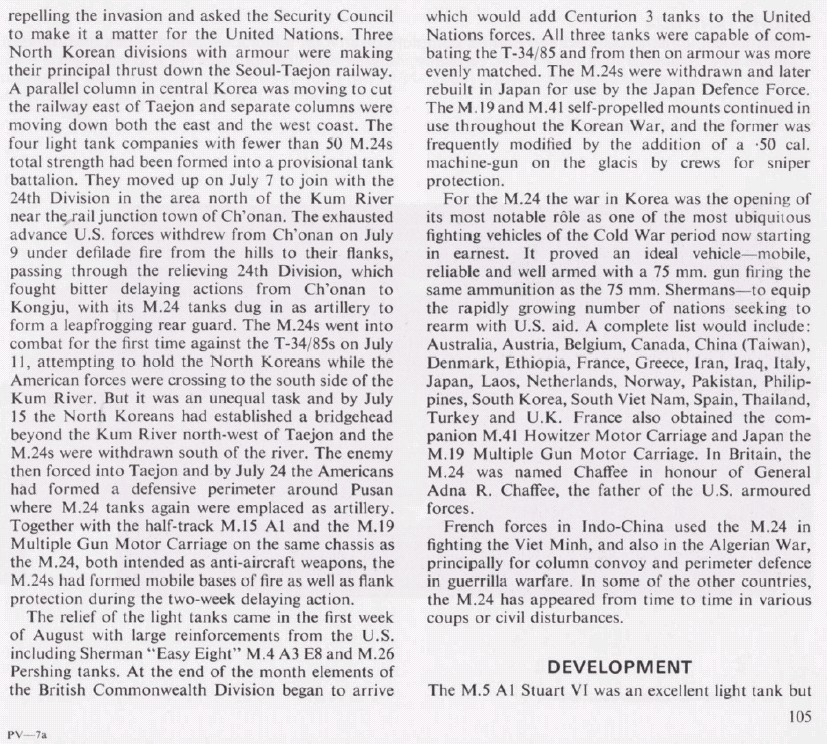

1950: Disaster with Tank-less Task Force Smith in Korea

The result will be the M24 light tanks assigned to the 24th Infantry Division in Japan are not flown in by USAF aircraft along with Task Force Smith, that proceeds to get itself over-run by North Koreans with T34/85mm gun medium tanks. The M24s are brought over later by ship to the Pusan perimeter where they are at least able to hold off the heavier gunned T34/85mm medium tanks until Shermans and M26 Pershings with 90mm guns can be scraped together.

Page 105, Colonel Icks praises the M24 to the hilt.

Had the Airborne and Infantry branch not attempted to duck responsibility for its own AT/assault capabilities (foisting the job onto lazy tankers who don't want to fly), and been alert, M24 Chaffees or better yet--M18 Super Hellcat light tanks with 90mm guns superior to the Communist 85mm guns would have been ORGANIC to the infantry division--and USAF air delivery means secured to fly them to the fight.

Research shows even as things were, M3 half-tracks could have been flown underneath USAF C-54 four-engined transport planes to accompany TF Smith to Korea. Once there, 75mm pack howitzers or 75mm recoilless rifles, quad .50 caliber heavy machines guns could have been fitted to them for firepower and the half-tracks could have transported TF Smith infantrymen and towed artillerymen with some armor protection from NORK enemy fires--and insured they withdrew in good order. So the question remains how could the turreted M24 Chaffee or had we been-on-the-ball, M18 Super Hellcats with 90mm guns with overmatching firepower could have got to the fight using what was available at the time?

Lower the River: Make the Light Tanks Lighter

The first answer is of course NOT HAVE A TURRET like the most successful tanks of WW2, the German STUGs were arranged, to save weight and lower vehicle height while insuring powerful gun armament able to kill any sized enemy tank. More on this later.

Could M24/M18 turrets have been temporarily removed for USAF C-82/C-119 air transport and then re-assembled once in South Korea?

C-119 Flying Box Car

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fairchild_C-119_Flying_Boxcar

We already know the answer here. YES.

A mere 5 men and 3.5 hours of work into (2) loads. If turrets were removed from the M24/M18s, they could have been transported in less than 10-ton payload stages by C-119s to Japan and re-assembled to fire support TF Smith. We know this because of our own tests---and even the cash-strapped French did this in Indochina 4 years later delivering 10 x M24s to Dien Bien Phu. So really, there is no excuse.

Therefore, a lot of the blame rests on the Armor branch "tankers" having a good time chasing Japanese wine, women and song during occupation duty for not having developed the vigor to fly themselves to battle in pieces to pitch in and help.

This convenient, flimsy self-created excuse that one's tanks are "too heavy to fly" is often used by those in Armor branch and can been by the thousands of their tanks sitting in motor pools collecting dust here in CONUS when the USAF has C-17 Globemaster III turbofan jets that can fly ANY of them--even 70-ton M1 Abrams heavy types to any place in the world--as the infantry gets creamed on foot and in absurd road-bound wheeled trucks in Iraq/Afghanistan. As we will see, this excuse was NEVER true--even when we were limited by piston-engined aircraft!

Raise the Bridge: Making Aircraft Larger to Fly Existing Light Tanks

Gliders: What Was Wrong with American Gliders in WW2?

The first conclusion was that as typical, know-it-all Americans we didn't see any military use for gliders until the Germans "got in our faces" and seized Crete in 1941. Then, we went crazy on a crash-course to catch-up--and begin handing out contracts to anyone promising they could build gliders. Many men lost their lives in poorly constructed gliders, giving the concept a bad reputation--when actually it was due to American ignorance and incompetence.

What Made our Gliders Large Enough to Carry Jeeps?

Was it USAAF General Henry "Hap" Arnold ordering a "Flying Jeep"?

U.S. Army Report: "Development and Procurement of Gliders in the Army Air Force 1941-1944"

combatreform.org/Development-and-Procurement-of-Gliders-in-the-Army-Air-Force-1941-1944-USA-1946.pdf

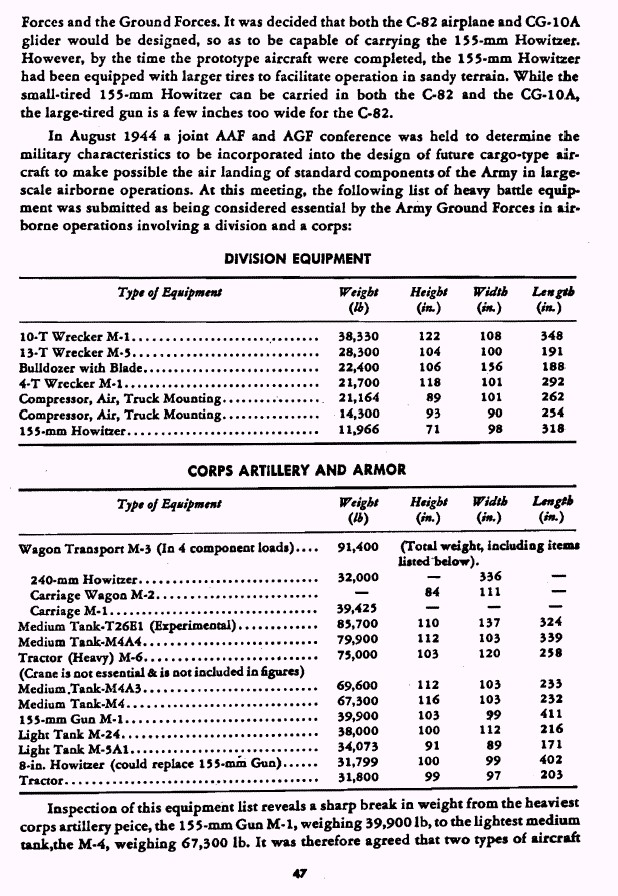

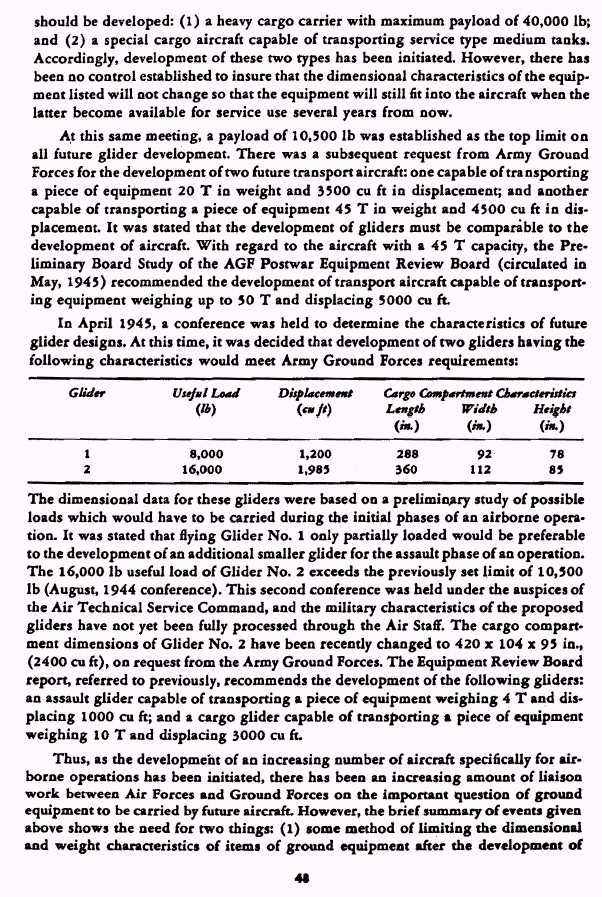

On page 44 on the PDF document:

combatreform.org/generalarnoldsuggestsflyingjeep.jpg

Or British Jealousy Since their Gliders could carry Tanks?

combatreform.org/vonkarmansayshamilcarandlighttankjealousyledtojeepglider.jpg

Von Karman in his 1945 report on future Airborne warfare [combatreform.org/VKarman_FutureAirborneArmies_C5.pdf] contradicts the Arnold explanation and says it was jealousy after seeing the British Hamilcar glider that could carry a LIGHT TANK, that the USAAF insisted its gliders at least carry a jeep or a towed gun.

_____________________________________________________________

SIDEBAR: Flying Jeep Gliders? Combination Air/Ground Vehicles?

combatreform.org/vonkarmanairbornegrasshopperspage33.jpg

Karman also calls on the Airborne to have a folding-wing, STOL observation "grasshopper" plane that could be parachute dropped and even drive itself on roads! Similar to what Arnold wanted by a jeep that could fly.

combatreform.org/vonkarmanwantsflyingjeepairgroundvehicle.jpg

_________________________________________________________

So What Happened to Post-WW2 U.S. Gliders? Why Were They Not Made to Deliver Light Tanks? (One model was)

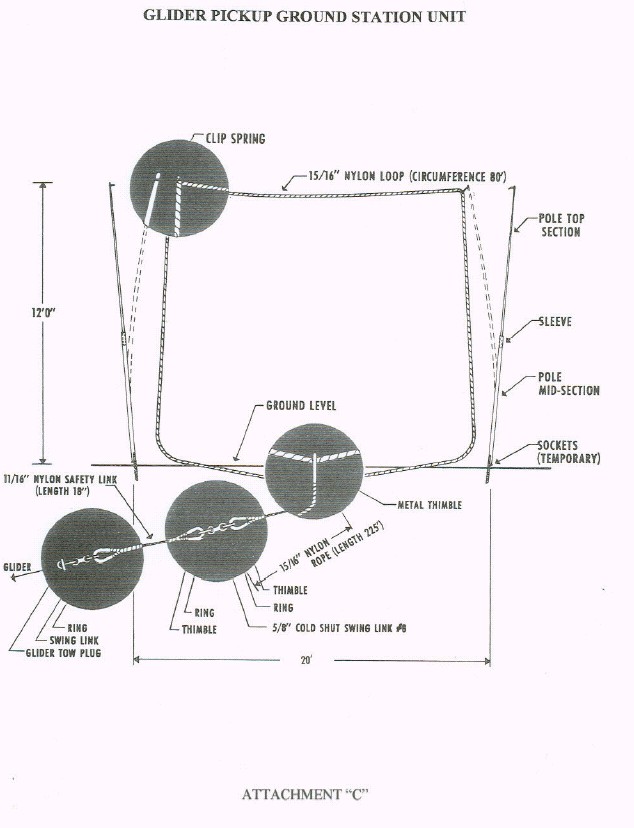

No Power; Towed into the air and to the Assault Zone, Snatched or discarded

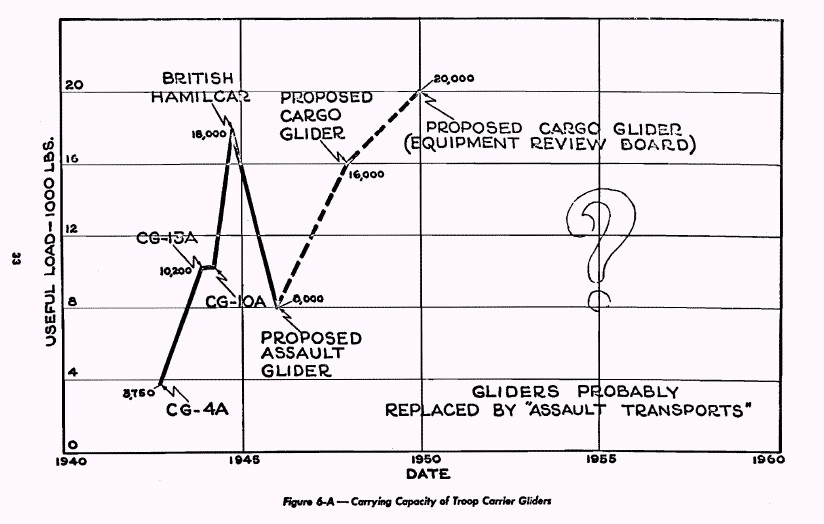

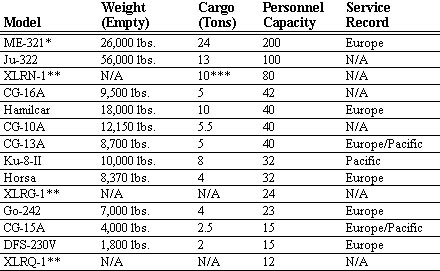

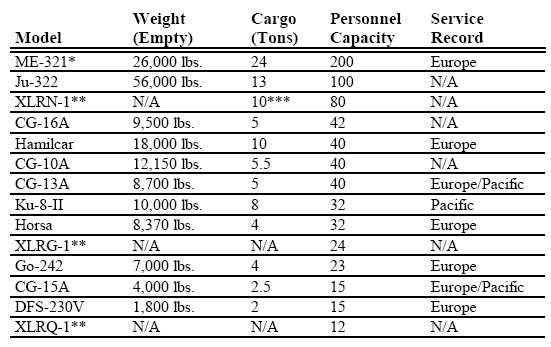

The short answer is there was no excuse. As said before, in WW2 we could have got the plans from the British and built copies of their Hamilcar gliders to transport our own M22 Locust light tanks. These could have been improved after the war. Von Karman shows the pathetic state of U.S. glider payload capabilities far short of the British in the chart below.

combatreform.org/vonkarmangliderprogresschart.jpg

The long answer is contained in the long AAF glider report.

"Reader's Digest" summation:

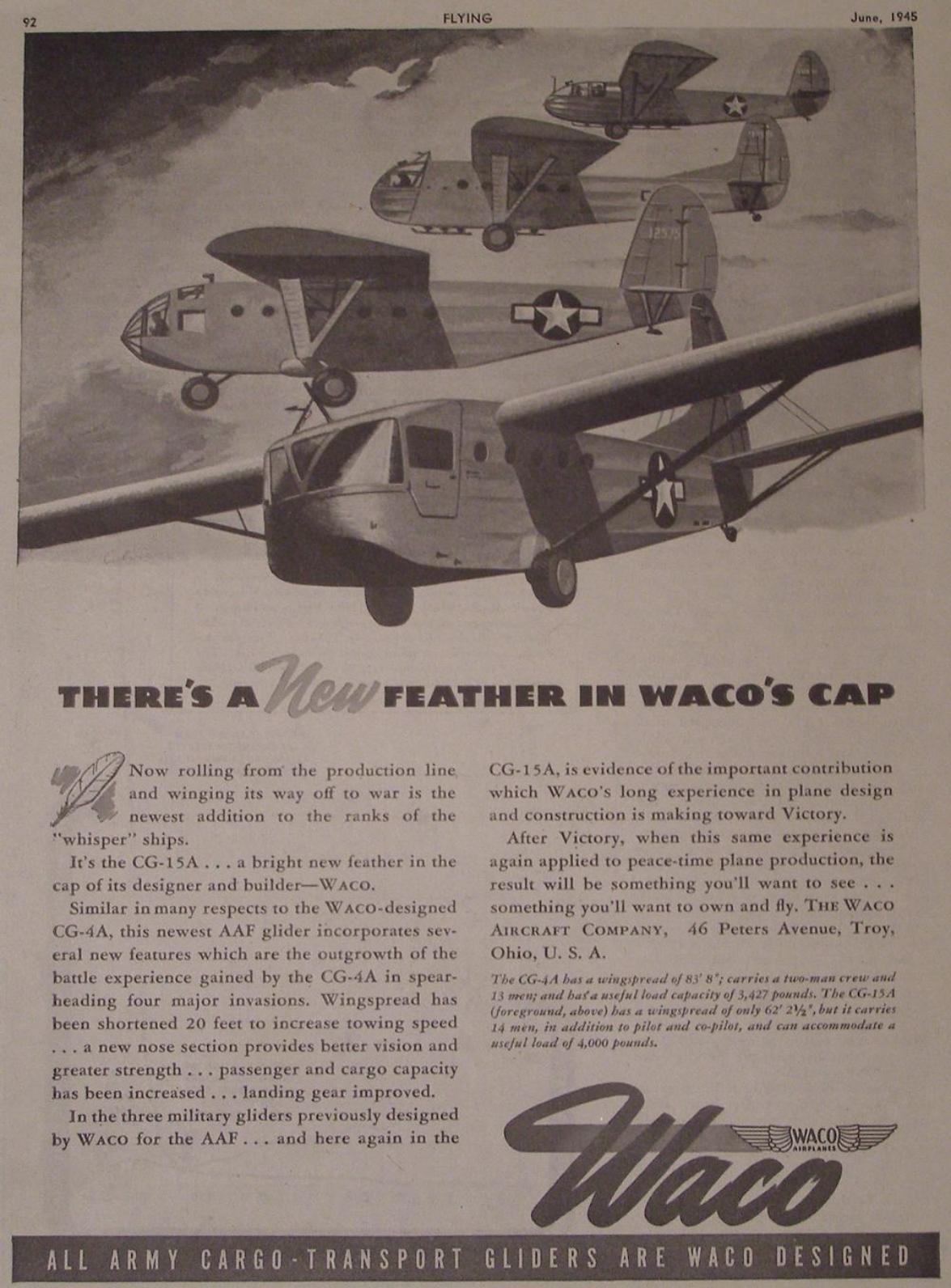

Basically, the Waco CG-4A that could carry either a dozen infantrymen or one jeep or one towed gun (but not both at the same time) was GOOD ENOUGH for us to get by in WW2; so they mass-produced it and ignored larger gliders. Even the mildly improved CG-15 version of the CG-4A was too much deviation and not mass-produced.

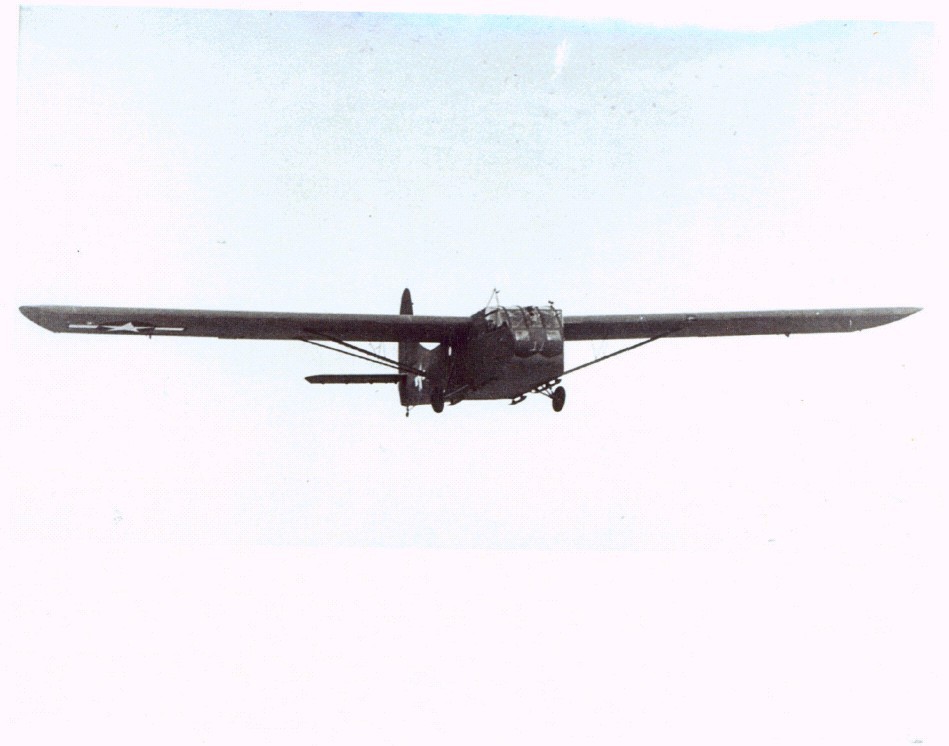

CG-15

The CG-15 had less wing span in order for it to be towed at faster speeds. Had better pilot visibility and crash-worthiness.

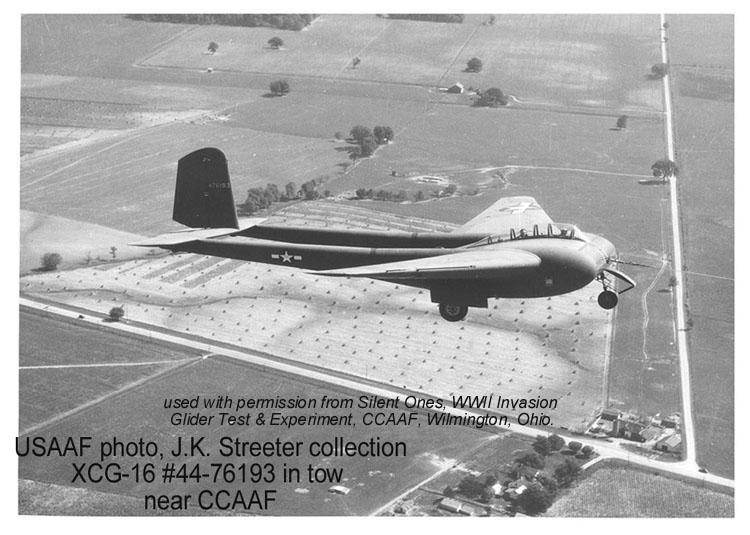

CG-16

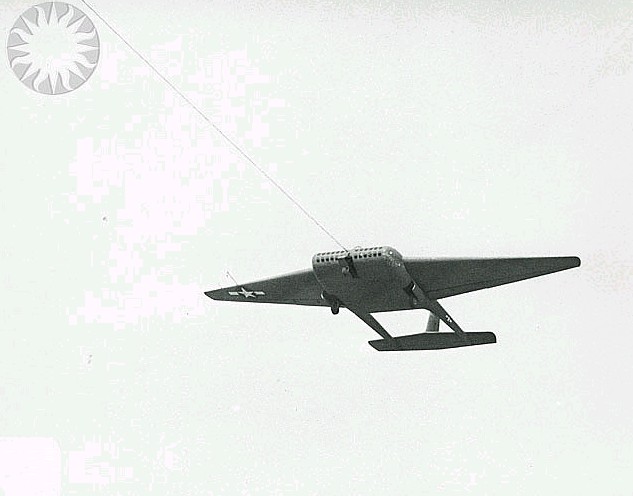

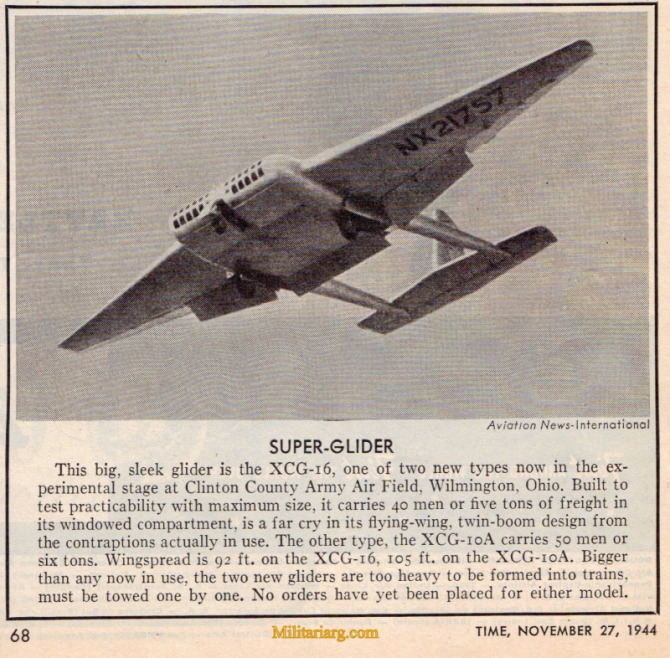

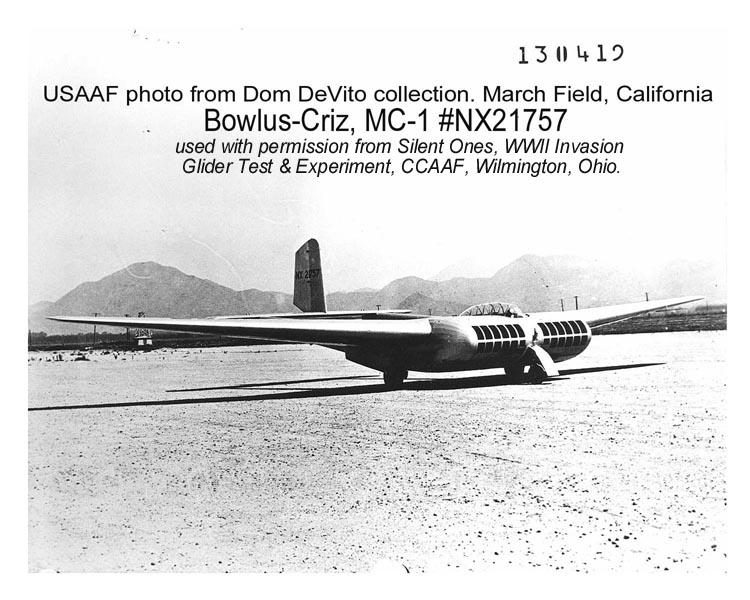

The infantry-centric mentality U.S. Airborne division wagging the logistics tail. As WW2 raged, when innovative designs like the Burnelli-style flying wing XCG-16 appeared, there was no time to pursue it, even though it offered a cushioning ground effect upon landing. Had the CG-16 been supersized to carry a light tank it would have offered a compelling capability.

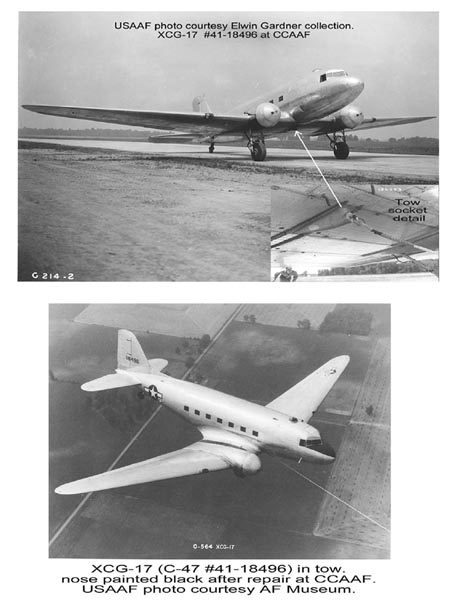

CG-17

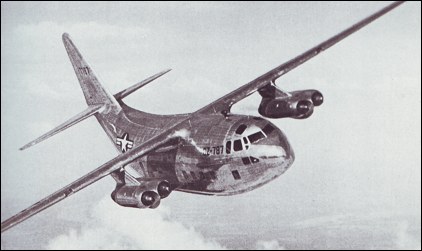

A sharp AAF LT suggested removing the engines from a C-47 and making it into America's first all-metal glider. It worked! It worked so well, it could be towed over 200 mph and carried more cargo than a powered C-47!

So why didn't they make C-47 gliders? The bureaucracy claimed that the C-47 couldn't crash land like a purpose-built glider. Charles Day writes:

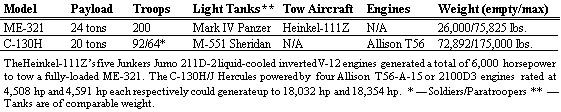

The XCG-17 could carry 49 troops or three Jeeps or two 105mm howitzers with small tires. In comparison, the XCG-10A could carry 42 troops or two 105mm howitzers with combat tires or one 155mm M1A1 howitzer or one 2 1/2 ton 6x6 truck or one 1 1/2 ton 6x6 truck. Despite superior flight characteristics, the XCG-17 was deemed unacceptable because it did not fit the USAAF glider requirement that it be capable of landing on unimproved areas normally not suitable for aircraft.

Excuse me, but the C-47 with wheels retracted has a part of the wheel exposed for the very purpose of making belly landings smoother.

combatreform.org/gasolinejeepcausedburnedupglider.jpg

Airborne Soldiers would have been better protected during the assault landings, saving many lives. It seems the real reason was the bureaucracy was already committed to CG-4A mass-production using non-airplane steel tubing and wood and didn't want to change and start using powered airplanes made of aluminum for the task.

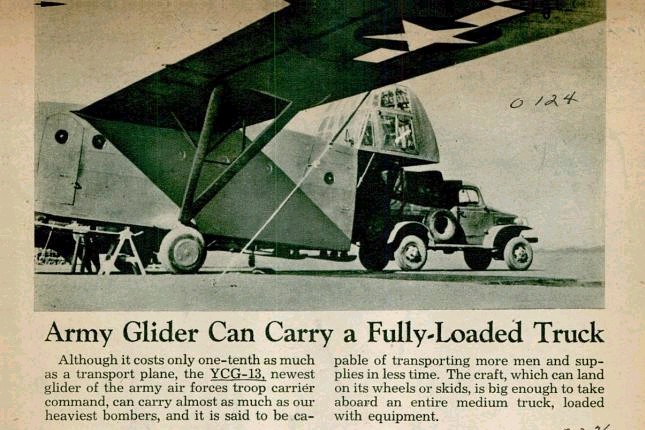

CG-13

The only large glider selected by the AAF to be built was the CG-13--that could carry 30 troops or a towed gun and a jeep. It was used once in the Pacific during the Aparri jump in the Philippines in 1945.

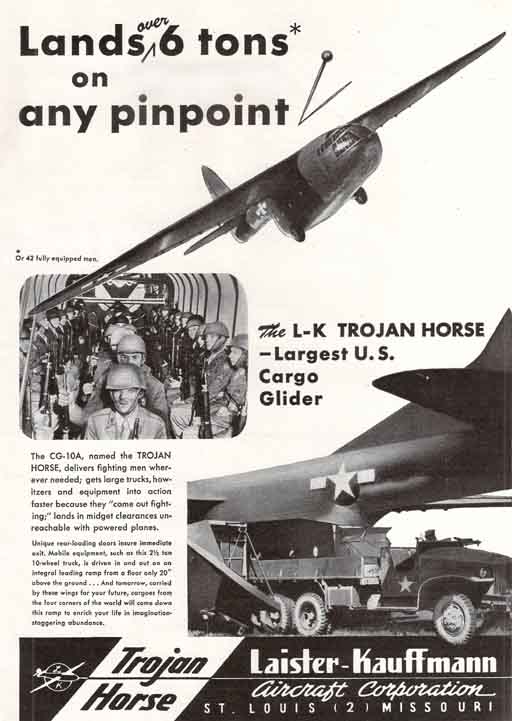

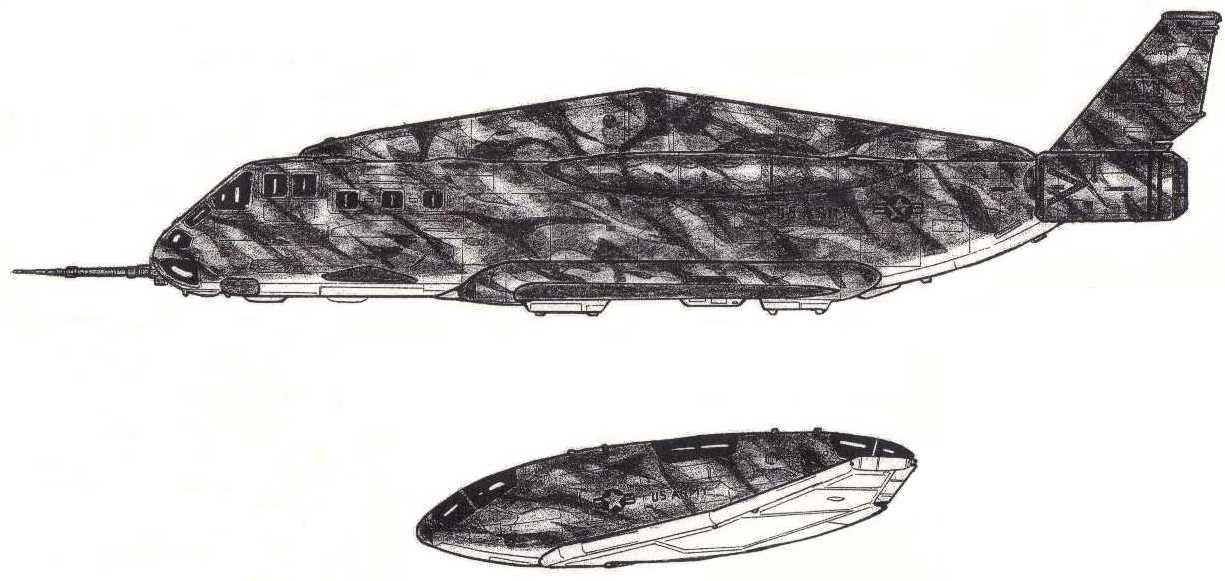

At WW2's end there was more enthusiasm for the XCG-10A "Trojan Horse" which featured a rear loading ramp, but could only carry 10, 000 pounds of men or cargo---the nose-loading British Hamilcar already carried 16, 000 pounds (8T) into combat several times in combat.

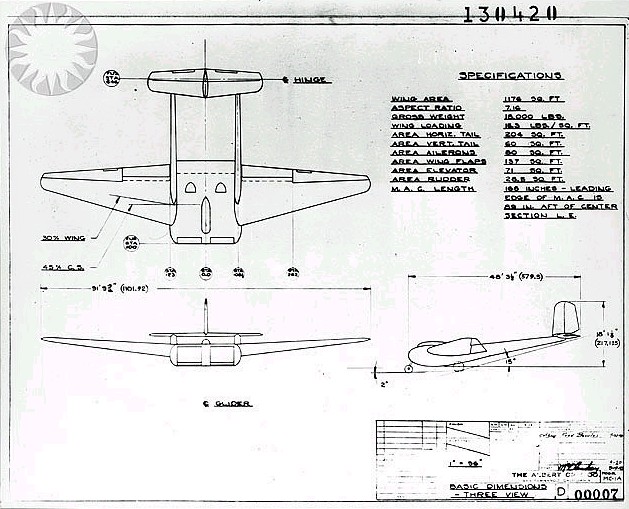

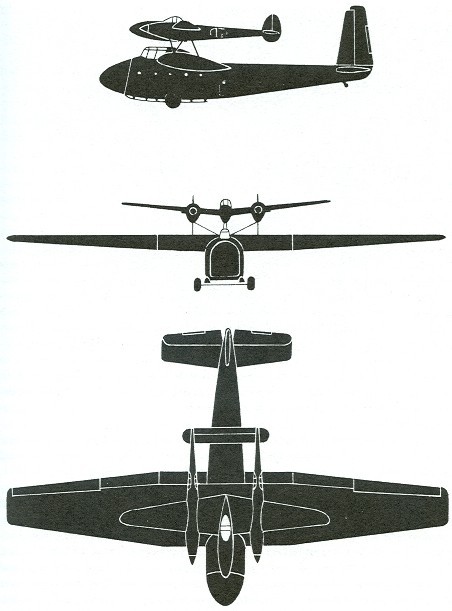

CG-10 "Trojan Horse"

The XCG-10 was a large military glider capable of accommodating 30 troops or a freight load of 5 short tons. It is a high-wing cantilever monoplane with a deep forward fuselage tapering to a tadpole boom which supports the tail unit. At the break in the bottom lines of the fuselage clam-shell doors give access to the main hold 30 ft.(9.15m) long, 7 ft. (2.14m) wide and 8 ft. 6 in. (2.59m) high, which can accommodate a 155mm howitzer or a 2 1/2 ton truck. Structure is entirely of wood with plywood covering. The wings are fitted with Fowler-type landing flaps and have an overall span of 105 ft. (32m). (info from Jane's Fighting Aircraft of World War II)

Additional info from Charles Day, "The XCG-10 and XCG-10A were two different craft. The 10 was a 30 place glider and the 10A was 42 place. Although some sources say the 10 did not exist and the project was changed to 10A in design stage, the 10 was built both as a static test article and a flight test article. The internal hold size was slightly larger for the 10A to accommodate the GM 6X6 truck. The wingspan stayed the same."

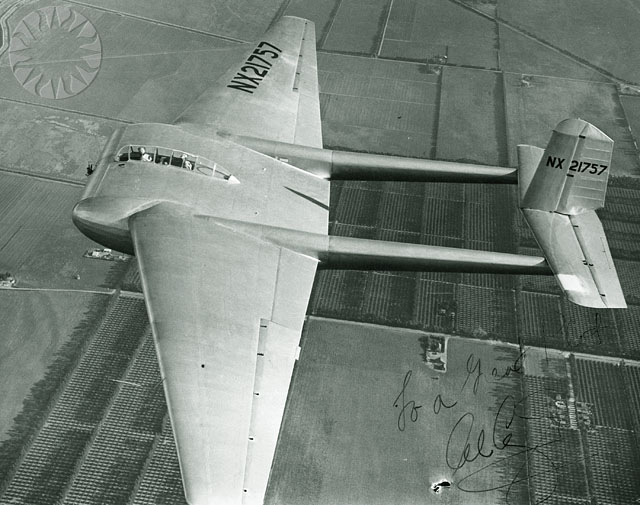

CG-20

WW2 is now over, and all-metal construction is now a possibility. The Army Airborne is still interested in gliders.

Karman describes a convoluted mess. It does list the M24 Chaffee light tank at 19 tons on the Army's shipping list of items desired to fly by air.

vonkarmanidiotic1945transportandgliderdecision1.jpg

vonkarmanidiotic1945transportandgliderdecision2.jpg

It appears the Army brain trust Karman is interfacing with does not realize that the Airborne needs to get light tanks to the fight with something NOW--and not lust after a mythical 50 ton aircraft to lift medium tanks--which incidentally will not arrive until 1969 with the C-5 Galaxy turbofan jet transport. Perhaps realizing this by reading General Gavin's 1947 book Airborne Warfare, on 2 December 1946 Chase Aircraft gets a contract to build two prototype gliders--and they decide to build really big all-metal gliders--big enough to transport light tanks.

www.globalsecurity.org/military/systems/aircraft/cg-20.htm

The CG-20 could take off at 70K--but was limited to 40K due to weak tow planes that were available. Apparently no one considered using JATO rockets to help...the Germans used rockets to lift their Me321 heavy gliders into the air...

www.aviastar.org/air/usa/chase_xcg-20.php

When mounted with 4 x J47 engines, the CG-20 (C-123A) weighed

25, 000 pounds

Each J47 engine weighed 2,707 pounds, so 4 x 2700 = 10, 800 lbs. total

Thus, we can conservatively estimate that the pure glider CG-20 minus the J47 jet engines weighed 15, 000 pounds empty

70K - 15K = 55K total payload

According to C-123 Provider in Action by Al Adcock, page 4, the CG-20's cargo compartment was 30 feet (360 inches) long, 12 feet (144 inches) wide and 10 feet (120 inches) high.

Clearly, the CG-20 had enough space inside for a M24/M18 light tank to fit inside and enough wing lift to be towed into the air to deliver them to the battlefield by crash-landing. In fact, the larger M41 that replaced the M24 at 23.5 tons and 126 inches could also be carried by the CG-20!

Low Power; Towed into the air and Assault Zone, Flies Self Back

If two small engines were fitted, the CG-20 empty could take-off and fly itself back to base if the assault landing zone was suitable. The U.S. modified a CG-4A with engines to enable self-recovery. Another fascination idea was to tow the low-powered glider to get it into the air, then disconnect and let it fly itself to the assault landing zone since it takes more power to take-off but less to stay aloft. The British Hamilcar with a P-38 Lightning on top as a powerplant/parasite fighter was an extremely clever idea with lots of tactical capabilities we should have at least tried. Details:

combatreform.org/airbornewarfare.htm

Full Power: Flies Self to Battle and Back

In fact, with 4 x J47 jet engines the CG-20 (C-123A) could take-off with 60K, so 60K - 25K = 35K total payload = still enough to fly the 17-ton M18 Hellcat up to speeds of 500 mph! Wow. Fantastic for 1950, huh?

Yet at the time, the USAF rejected the jet-powered CG-20 because its J47 engines were under-slung the wings and it ingested dirt. A flimsy and suspicious excuse from a service bureaucracy that always embraces any excuse to stay near pampered air bases. Why didn't anyone suggest PUTTING THE ENGINES ON TOP OF THE WINGS like the Fokker VFW614 commuter airliner?

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/VFW-Fokker_614

The aircraft was revealed to be of unconventional configuration, with two quiet, smoke-free, but untested M45H turbofans mounted on pylons above the wings. This arrangement was used to avoid the structural weight penalties of rear mounted engines and the potential ingestion problems of engines mounted under the wings, and allowed a short and sturdy undercarriage, specially suited for operations from poorly prepared runways.

Or at the top of the wings and using exhaust for Coanda effect like the YC-14 or the Russian AN-72 Coaler?

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Antonov_An-72

An unusual design feature of the An-72 and An-74 is the use of the Coandă effect to improve STOL performance, utilizing engine exhaust gases blown over the wing's upper surface to boost lift.

The bottom line here is that the U.S. Army/Air Forces, and then the USAF made a mistake and should have purchased CG-20s in SOME CONFIGURATION in order to deliver M24/M18 light tanks for an immediate operational capability. These could have been ready by the time of TF Smith in Korea in 1950. Instead, everyone was too busy having fun celebrating the end of WW2.

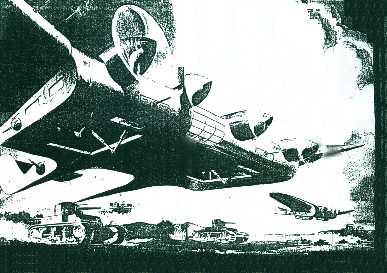

Free Dropping Tanks or Kiwi Pods, Possibly Glider Kiwi pods

As bizarre as this sounds, the Russians had already dropped modified light tanks from a few feet above the ground from under low flying bombers. Photos and video:

combatreform.org/concepttoc.htm

The problem is getting the tank's tracks to go fast enough to meet the lowest possible speed of the plane to stay only a few feet above the ground or briefly to touch down.

combatreform.org/freedroplighttanks2.jpg

The goal is to not need a runway-but to be able to use any grassy field. Von Karman suggests instead of dropping the tank directly onto the ground, have it in a wingless, "Kiwi" pod with wheels or a flat surface to slide fast enough to come to a safe stop.

combatreform.org/vonkarmankiwipods1.jpg

combatreform.org/vonkarmankiwipods2.jpg

Powered Transport Aircraft

Working with the 1945-50 time frame of demobilization and no monies, what could have been done to transport turreted M24s/M18s if one was too lazy to remove them and reassemble them? What if you needed them to fight immediately after air delivery?

USAF 1945-1950 Options to Fly Turreted Light Tanks

B-29 Superfortress

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Boeing_B-29_Superfortress

Let's say the USAF really cared about getting the U.S. Army Airborne to the fight. The B-29 was 75K empty and could take-off at 130K so it had a 55K payload potential--easily enough to carry a 48K M24 Chaffee/M18 Hellcat light tank if armament gun turrets were stripped and the bomb bay modified so their turret fit inside and the rest of the tank hull dangled out into the slipstream. Surely, with the 4, 000 B-29s that were mass-produced, the USAF could have spared at least 100 to fly light tanks for the Army Airborne?

C-54 Skymaster

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Douglas_C-54_Skymaster

Since we know the USAF obsessed with winning wars all by itself via strategic bombing firepower did NOT care much transporting the Army for maneuver, so B-29s would not have been offered. Therefore, what could have been done with the C-54 transport plane to transport a turreted M24/M18 light tank of up to 48K?

First, longer-legged landing gear would be needed to carry the turreted light tanks underneath to have adequate clearance for take-off and landing. Once this gear was in use, it obviously could not retract into the space of the shorter landing gear well, so a NEW WING would be required. This is ok, since a LARGER WING would provide more lift and--an extra set of engines for a total of 6. A four-engined C-54 was 39K empty and 73K loaded--for a total of 34K of payload. The question is would a 6-engined C-54 with a larger wing and longer landing gear have say a payload of 55K to comfortably transport a 48K light tank and have 7K of fuel?

German scientist Von Karman in his report on future Airborne warfare offers a 6-engined Kiwi pod transport plane.

combatreform.org/vonkarmans6enginedkiwipodplane.jpg

An actual Kiwi pod plane was built using the C-119 as the starting point for a glider-pod dropping capability.

XC-120 Pack Plane

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/XC-120_Packplane

www.flightglobal.com/pdfarchive/view/1950/1950%20-%201769.html

Video

www.youtube.com/watch?v=9gspWjduh3Q

www.youtube.com/watch?v=9gspWjduh3Q

A C-119 without a fuselage--the XC-120--could have carried a M24/M18 light tank underslung--the question is could it have taken off with say a larger wing and 4 engines or with turbojets in pods or turboprops? The C-119 and XC-120 had two x 3, 250 hp piston engines for a total thrust of 6, 500 hp and were capable of lifting 10 tons of cargo. Without the cargo pod weight or the C-119's built-in fuselage, the XC-120 as-is could lift another 1-2 tons if the payload were attached directly underneath.

Stanley H. Evans in his superb article "Cargo Carrier Concept: Design-logic for Airborne Logistics: The Fairchild XC-120 Pack-plane". Flight magazine 21 September 1950, pages 331-333 makes an excellent case for a Burnelli design pack plane with turboprops. He notes that the T40 contraprop engines (used in the later R3Y1 Tradewind seaplane transport) were planned for future XC-120 planes. We know now, this didn't materialize and that the T40s were mechanically unreliable--but the concept of contra-rotating props to get 2 engines in the space of one is SOUND and is proven every day in Russian Tu-95 Bear bombers that have been flying successfully for decades since the 1950s. Had reliable British Mamba contraprop engines used in the Fairey Gannet ASW carrier-based plane [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fairey_Gannet] been fitted to a XC-120, 4 x 3, 875 shp engines would have offered 15, 500 shp of thrust--this is over 2x the thrust of the 2-engined prototype. Almost 3 times the power. We will call this the "XC-120T". The XC-120T payload would have increased to over 25 tons to easily transport M24/M18 light tanks.

Comparison/Reality Check

The R3Y Tradewind [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Convair_R3Y_Tradewind] had 4 x unreliable 5, 100 shp T40 contraprop engines for a total of 20, 400 shp thrust and could carry 48K payloads routinely. Empty weight was 72K and max take-off was 165K--so maximum payload potential was 93K--subtract a 48K M24/M18 light tank and one has 45K on crew, fuel etc. to work with. Plenty to work with.

Available USAF 1950-1960 Options to Fly Army Light Tanks

So the Army's tankers are "fat and happy" with their M24 Chaffees and M41 Walker Bulldog light tanks throughout the 1950s. They don't have to risk their necks flying in aircraft and parachute jumping. They haven't made themselves air-deployable. The USAF drastically improves its airlift capabilities by the turboprop C-130 Hercules STOL transport. Here is where things get very interesting....

Will a M24 or a M18 fit into a C-130 fuselage?

The M24 is listed as 9.84 feet wide (118 inches) and 9 feet high (108 inches) high--too wide and too high by a small margin. The M18 is slightly smaller at 9.4 feet (113 inches) wide and at 8.4 feet (100 inches) high is significantly lower than the M24.

The USAF lists 104 inches as the maximum height for a load to tip-off the rear ramp during airdrop. The M18 Hellcat is good-to-go height-wise. Why couldn't the M24 be modified to lose a mere 14 inches of height by a kneeling suspension and smoothing the turret top?

The USAF lists 105 inches as the maximum C-130 floor width allowable---but this includes two sets of 463L pallet rollers representing a total of 18 inches. So the actual C-130 maximum floor width is 123.2 inches and this narrows to 119.5 inches at the wheel well center area; not a lot to work with when backing in a M24--but do-able. No problemo for the M18 Hellcat! Why couldn't lighter weight band tracks perhaps on narrower on narrower roadwheels been developed for a few more inches of aircraft wiggle room?

Or why didn't the USAF insure when they wrote the specifications on the C-130 that they insured a M24 light tank would fit and be air-transportable?

C-130 Cargo Dimensions

www.456fis.org/THE%20AC-130/c-130-cargodims.gif

A problem area of the C-130 is its landing gear bulge half-way into the fuselage cargo floor--and half-out into the slipstream. If we had C-130s with their entire gear held in external bulges like the C-160 Transall this would free up the cabin floor for 123.2 inches of width from beginning to end and make it easy to load/unload as-is M24 Chaffee light tanks. In-flight refueling probes like the RAF C-130s have would enable a Herk with a M24 to take-off with a light fuel load and top-off for long-range missions.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Transall_C-160

Clearly, the answer is YES; the M18 Hellcat--which is the superior light tank in performance---and the M24 Chaffee with some work--could have fitted into a C-130 for the Army Airborne in the 1950s. Both could have been up-gunned to 90mm guns to stay ahead of the threat. So the fault here lies with Armor branch for not applying itself to help Airborne units by getting themselves to the fight by available aircraft and parachutes. One way to not have to become Airborne is to deliberately adopt a tank that cannot be airdropped with what was available.

Enter the M41 Walker Bulldog light tank in 1953

[http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/M41_Walker_Bulldog] has an even better combat record than the M24; tested in Korean combat and later in use by the South Vietnamese Army, they successfully defeated Communist T-54/55 medium tanks in repeated combats with the same 76mm gun used by the M18 Hellcat--which begs the question of why wasn't the latter used all along after closing its turret top?. Surely, the M41 was a light tank the can't-ever-have-enough-armor-protection tankers would embrace...

However, the steel M41 was 23.5 tons and too wide at 126 inches to fly by C-130. It's almost as if Armor branch deliberately designed the M41 so it could not fly by widely available C-130s...But remember if we had adopted CG-20 gliders--we could have flown even M41s by them! Unless of course, Armor branch deliberately moved the vehicle's size goal posts again to wimp out from being air-transportable.

C-124 Globemaster II

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Douglas_C-124_Globemaster_II

The biggest transport after the C-130 in USAF service was the C-124 Globemaster II, introduced in 1950 could carry and AIRLAND a M41 Walker Bull Dog light tank through its front loading nose door--but could not airdrop vehicles in flight. There were a few C-133s that had rear ramps to paradrop M41s--but this option wasn't pursued.

What About Using Light Tanks that Armor Branch Tankers Didn't Like?

So the Army Airborne adopts the 8-ton M56 Scorpion tracked self-propelled 90mm gun on an exposed mount--when the superior fully-enclosed 9-ton M50 Ontos with 6 x 106mm recoilless rifles was available and advocated by Airborne pioneer LTG James M. Gavin. The Ontos would kick serious ass in Vietnam with the not-too-bright marines--who would then retire then when they ran out of spare parts and couldn't figure out how to make newer variants using the widely available M113 Gavin chassis. The French 15-tons empty AMX-13 light tank (initially automatically-loaded version of 75mm used on German Panther medium tank, later replaced with 90mm and 105mm) was also available that is C-130 air-transportable, why didn't we buy some of them?

combatreform.org/airbornetanksnoexcuse.htm

Again, a suspicious subjectivity appears in play here.

Summary of the 1945-1964 Period of American Airborne Development

When the U.S. Army lost control of gliders to the USAF (?), an important opportunity to deliver light tanks by new heavy payload gliders was lost. Until 1953, the M24 Chaffee was the light of the U.S. Army--and even well-liked by the tankers. The CG-20 glider could have lifted the M24 had we thought of towing it with the most powerful plane we had with the assistance of rockets. Therefore from 1945 to 1958--before the advent of the C-130--the CG-20s could have--and should have air-delivered M24s (or better yet lighter M18s Super Hellcats with 90mm guns) to help the Army fight on the ground in Korea and be ready anywhere else in the world. True, in 1953, heavier M41 Walker Bulldog light tanks had replaced M24s, but to create an airdrop capability with the C-130, why not keep a battalion's worth of M24s--or better yet M18 Super Hellcats? They are already bought and paid for, and we are handing them to our allies for free. Why develop the exposed M56 Scorpion for parachute airdrop at all if you had CG-20 gliders or knew turboprop C-130s were coming with payloads and rear ramps that could crash-land or airdrop M24s or M18s so Paratroopers could have immediate fire support? Or did we get complacent and took the low road and felt compelled to seize a runway so M41s could be airlanded by C-124s so tankers wouldn't have to go on jump status?

While all of this was going on, the Russian Airborne VDV were parachute-dropping the open-topped, armored ASU-57 with the proven WW2 57mm AT gun--the same SPG concept that the British Alecto demonstrated years before. These weapons would provide critical firepower for VDV Paratroopers dropped behind enemy lines to blast anything in their path. The M24 and M18 were far more capable than the ASU-57--and we had the means to air-deliver them--and we didn't even try.

THE FAILURE OF HELICOPTERS FOR COUP DE MAIN

Helicopters are noisy, slow, use a lot of fuel and do not have long range. And this includes the ballyhooed V-22 Osprey tilt-rotor helicopter cum airplane. The Son Tay raiders crashed their primary assault team helicopter into a North Vietnamese POW camp rather than even try to fly out. Thus the 101st Air-Assault Division likes to fly in her helicopters carried on-board USAF jet transports that land on runways or assault-zones seized by the 82nd Airborne Paratroopers jumping in with parachutes. As this force maneuvers to defeat the enemy, helicopters are used to deliver troops directly onto assault objectives like gliders used to be used. The problem is helicopters are not stealthy like gliders, thus, the enemy is waiting and the helicopters often get clobbered. In 1975, marines were creamed by heavy machine guns and RPGs on Koh Tang Island. Helicopters got shot down assaulting positions on Grenada, the marines lost 2 Cobras and several transport helicopters to enemy ground fire from hardly a "high intensity" conflict, the MH-6 "Little Bird" helicopter that rescued Kurt Muse from the roof top of Modelo prison in Panama in 1989 was shot down, and two helicopters were shot down in Somalia that created the desperate situation on October 3, 1993. The use of helicopters for direct assault on the increasingly urbanized battlefield is questionable. There has to be a better way.

At least for high risk, high priority missions where absolute stealth is required. Its time for a return of the glider. This time without towing.

FIXED-WING HIGH-TECH GLIDERS

www.youtube.com/watch?v=GlN9oFX6YKY

www.youtube.com/watch?v=GlN9oFX6YKY

TECHNOTHRILLER: The Trouble in Treblestan

What we need is a fixed-wing glider that will hold a M113A4 Super Gavin light tank, and a squad of commandos made entirely of non-metallic material that will be carried sticking out the aft end of a C-130. The wings of the glider would be in the airflow. The men would sit inside the C-130 until time to get inside the glider and be launched. The closest analogy is the way Chuck Yaeger was launched from B-29 Bomber in a X-1 Rocket plane, which can be seen in the Book and movie, The Right Stuff. Instead of being in the belly/bomb bay, the stealth glider would be half in and half out of the C-130. The C-130 with its long range and speed would be able to carry the glider and its men to the insertion area. The men would get inside and the glider would be launched from a stand off range away from enemy detection. The glider would than glide silently into its landing points using state of the art navigation aids and forward looking infrared (FLIR). The stealth glider would be a unique shape with high lift capabilities like Burt Rutan's Scaled Compositesdesigns are like. Just before landing the slealth glider would have its wings pivot and flaps dropped to assist its barbed skids in landing within 20 feet. This was possible with World War II gliders and should not be that difficult to achieve today. The stealth glider should be able to land on a rooftop with precision accuracy----from there the commandos would jump out and assualt their objectives. Enemy would be caught by surprise with no warning. These gliders would be piloted by enlisted Paratroopers.

C-17 SkyCranes to Drop "Kiwi" Pods--and Gliders

ROTARY-WING GLIDERS

www.youtube.com/watch?v=58ADcUthPdo

www.youtube.com/watch?v=58ADcUthPdo

The long overlooked "glider" is the rotary wing AUTO-GYRO. Auto-Gyros are THE safest aircraft ever made. But they cannot hover--if they go slower than 15 mph they descend to the ground, slowly. They can take off and land VERTICALLY and are far simpler than the complicated helicopter which powers its rotors to fly all the time. in contrast, the Auto-gyro which predates the helicopter by a decade, is a ROTARY WING GLIDER, its rotors are NOT POWERED. As the Autogyro moves forward by a propeller of a jet engine, its rotors turn on their own to create lift, hence you have to keep going faster than 15 mph, which is not a problem. You can before reaching the target area, turn off your engines and SILENTLY come to a landing. Unlike gliders, if you want to abort the landing, you can turn the engines back on and fly away.

KIWI GLIDER PODS: GAVIN'S VISION

If we are smart, we will design the replacement for the CH-47D/F Chinook, the Future Transport Rotorcraft (FTR) would be equipped with detachable mission pods or "KIWI" pods like LTG James Gavin wrote about in his masterpiece Airborne Warfare in 1947. A special glider pod would detach in-flight and fly Paratroopers silently to assault objectives.

GETTING OUT: RECOVERY OF GLIDERS SOLVED

If we are using rotary-wing Autogyros, they can jump take-off themselves and fly themselves back to base.

If the objective is secure then helicopters could fly in and sling-load or re-attach KIWI pod gliders and fly the fixed-wing gliders back to their operating base. If the gliders are in a rural area, they could be fitted with a turbofan engine that would allow them to regain flight with takeoff JATO rockets and fly back to base. The gliders should also be lightweight and easy to disassemble for covert delivery to different parts of the world where needed.

The stealth glider is a low-cost weapon that can be developed to work with existing equipment that would be a great assest to special missions units and lead units of the XVIII Airborne Corps and USSSOCOM. "Out of the box" thinkers like Burt Rutan could pull this off on a "shoe string".

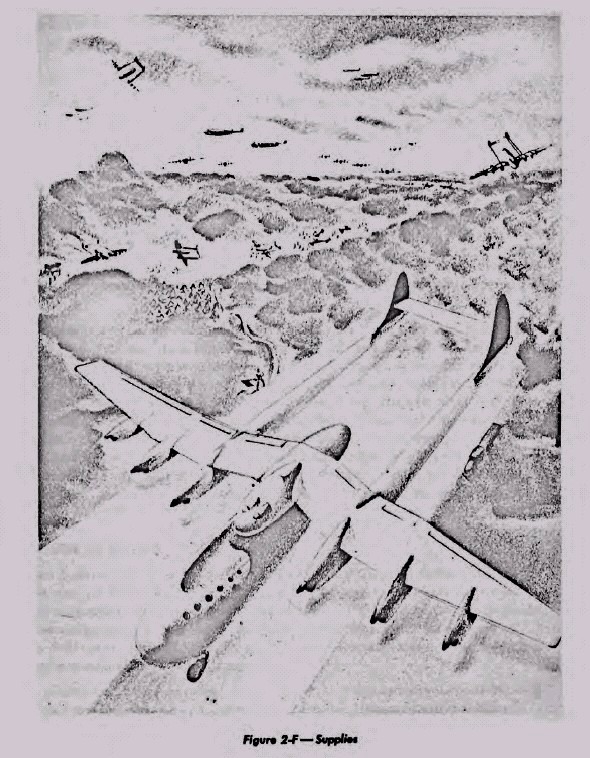

AIR-DELIVERED LOGISTICS BY GLIDERS

The down-side of parachute air-delivery is the cost involded in parachutes/air items if they cannot be recovered. A glider is in essences a sort of "Air-Trailer" like a ground trailer which uses its momentum to move cargo by rolling instead of carrying. The Air-trailer (glider) is a way to capitalize on the forward momentum already there of an aircraft to tow along a payload. Its long been known the the USAF needs more strategic airlift. A few years ago an article in U.S. Army Armor magazine called for a new glider to tow 70-ton M1 heavy tanks to the battlefield to solve our strategic lift problems. Kevlar type fibers would make tow ropes more reliable than in the past.

www.youtube.com/watch?v=jRLFTyHv-_k

www.youtube.com/watch?v=jRLFTyHv-_k

What I suggest to make the "Air-trailer" heavy glider work better would be not having a pilot onboard; use self-guidance to a GPS coordinate as now used in guided ram-air parachutes with a back-up remotely piloted capability via data link to an enlisted pilot inside the tow aircraft. The goal should be a capacity to carry a 70-ton M1 tank or 2 x M2/3 Bradleys or 4 x M113A3 Gavins.

The crews of these vehicles would parachute from inside the tow aircraft at a nearby Personnel drop zone for link-up later on the ground with their gliders. The Heavy gliders recovered by helicopter "snatch" then towed remote-control flying later.

These gliders have the capability to double the USAF cargo airlift capacity overnight and pose no threat to future purchases of transport aircraft since they are no good without something to tow them into the air.

FEEDBACK!

A military futurist from Great Britain writes:

"A bit of additional information that may be of interest for the glider page.

In 1940, Willy Messerschmit proposed that all tanks be fitted with brackets so they could have glider wings added on. The tracks would be covered by a sort of sled, and the idea was to tow the tanks over to England and let them land there. Don't know if it was intended for the crew to ride in the tank."

REFERENCES

1. www.airpower.maxwell.af.mil/airchronicles/cc/torrisi.html

Gliders: Rethinking the Utility of these Silent Wings for the Next Millennium

17 November 1999, Air & Space Power Chronicles by Steven A. Torrisi

Introduction

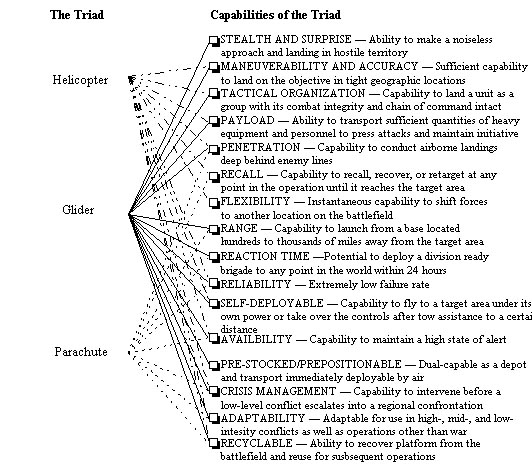

Current options for forced-entry operations need a tune up as the tempo and diversity of threats to United States security interests shift from a bi-polar to multi-polar world. Parachute drops and air-assaults by helicopter endure as the only mechanisms for the airborne insertion of troops and equipment. Units equipped as such require an alternative capability to drive or expand doctrine as traditional airborne roles mesh with non-traditional missions and rapid reaction forces continue to constitute the vanguard of crisis management. The answer necessitates fielding a conceptual aviation design that integrates a genuine stealth capability; a simple, yet sophisticated fuselage economical to manufacture; payload dimensions capable of deploying tactical formations; and, a combat radius enabling it to strike over extended distances and terrain barriers. Such an aviation design integral to airborne forces once existed in the inventory of the U.S. Army; the glider. Combat-proven in diverse wartime missions accents the credentials of these silent wings and makes it an attractive candidate for contemporary procurement and deployment. It is the intention of this article to ponder the benefits and potential obstacles to reinstating a glider capability which in turn may stimulate a renaissance of learning with regard to this neglected mode of flight.

Military Background

Born out of myth as an outlet for genuine scientific investigation into the feasibility of human flight, gliding or soaring, as it is commonly known, emerged at the turn of the century as a pastime and competitive sport

for the aviation enthusiast, domestic and international.1 Overnight the trademark of this endeavor, the glider, evolved from a cottage industry to an entrepreneurial venture as manufacturing plants sprang up to fill orders as improved designs came on the market. The outbreak of the First World War stifled glider development though as production lines shifted to a wartime economy and the military demanded propeller-driven aircraft for front-line service. Consequently, interest in soaring waned as newspapers chronicled the heroics of aerial combat over the Western Front. After the war, many industrialists from the allied powers poured funds and expertise into the development of a competitive aviation industry dedicated to powered flight; a move that did little to restore the glider's pre-war reputation as research and development (R & D) focused instead on building high-performance aircraft. On the other hand, a defeated Germany; the cradle of modern glider development; used the art of soaring as the perfect subterfuge to circumvent the Treaty of Versailles.2 Since treaty restrictions did not prohibit the operational use of gliders, the truncated Reichswehr under the leadership of General Hans von Seeckt sought to improve aeronautical technology and skill resources vis-a-vis subsidized R & D and civilian training programs; the goal: a cadre of pilots for a future air force.3 Inadvertently, the Allied Control Commission furthered this subterfuge when they relaxed the most stringent treaty constraints in 1923, on aircraft manufacturing in a move to stimulate industrial recovery; soon mass quantities of affordable gliders of high-quality design and construction were coming off the assembly lines.

The thought, however, of staging a vertical envelopment by means of glider traces its origins to the Treaty of Rapollo negotiated by Von Seeckt and Nikolai Lenin in 1921; this clandestine agreement among other things permitted technical exchanges between the German and Russian general staffs. Of those Reichswehr officers to benefit from this provision was an avid gliding instructor, Colonel Kurt Student. Having unprecedented access to Soviet military maneuvers during the early 1930s Student observed Russian advances in parachute operations were offset by the fact that the technology for delivering heavy weapons to the battlefield was non-existent. Natural fabrics such as silk, simply could not handle the load bearing capacity under extreme stress and fatigue causing the parachute to fail; tougher synthetics like nylon and rayon were still some years off. In his final tour of duty report, Student recommended the general staff take advantage of this deficiency by employing gliders as a cargo and troop transport, a proposal answered with a reply of skepticism and ridicule. Not until the advent of National Socialism could Student, now a major general and Inspector of Airborne Forces, turn his vision of a "heavy drop" into reality. Working with other proponents at the Darmstadt Airborne Experimental Center, akin to the Lockheed Skunk Works, Student co-wrote the milspecs for the first dual-purpose combat glider: the DFS-230.4

The very tactics and techniques arrived at by this early investment in glider development paid handsome dividends later on, in furthering the concept and conduct of the "blitzkrieg". As the sensational assault and capture of the supposedly impregnable Belgian fortress of Eban Emael by commandos landed by glider made headlines in 1940, the British enthusiastically reacted to

the pivotal role it played in this conquest by forming the Glider Pilot Regiment. The U.S. War Department, on the other hand, was quick to file intelligence dispatches from its attachťs stationed in occupied Europe mentioning the glider's importance as a combat weapon. Only after America entered the Second World War did the Army cease neglecting the potential of these motor-less aircraft for use in its newly organized airborne divisions

that went on to see combat in Europe and the Pacific.

After the war, demobilization eradicated most U.S. and British Army glider regiments.5 Four years later in April 1949, a relatively obscure milestone took place on the training ranges near Fort Bragg, North Carolina. Operation Tarheel, a month-long tactical exercise marked the final operational use of gliders by the 325th Glider Infantry: the last such regiment retained on active duty. Before the year was out, the Parachute School at Fort Benning, Georgia cycled its trainees through the last glider familiarization course. On January 1, 1953, the U.S. Army deleted glider landings from the capabilities of its airborne units as multipurpose transport helicopters, aircraft, and heavy cargo parachutes began to enter service. Army Regulation 670-5 issued on September 20, 1956, which authorized a glider superimposed over a parachute to serve as the formal airborne insignia, lives on today as the only indelible reminder of its former existence and contribution.6

Why Gliders? Why Now?

When you think of it, the art of war briefly comes down to a simple philosophy: success = my time + my place + my way. With dominance in all three parts victory is certain, two parts and one has a more than likely chance of success, and, with only one, defeat. The key to dominance is to create an un-level playing ground to your advantage by introducing new doctrine or equipment, or both before your opponent. However we in the United States tend to equate new to mean complex, high-tech, and expensive, a kind of establishment mentality brought on by an abundance of wealth in natural and intellectual resources that has become the opiate of today's military. Such thinking can cut both ways though, especially if a potential enemy ever recognizes first the utility of a piece of simple equipment discredited by the mainstream as obsolete or of little contemporary military value. The reason behind this is clear: an enemy cut-off or limited in access to wealth and technology cannot afford to be finicky when their national survival is at stake and so must have any type of edge to create that imbalance. If that gamble pays off on the battlefield, the mainstream must then rethink its position until it establishes qualitative and quantitative superiority. Once the threat is gone, said equipment remains in service long enough for another innovation to come along, then the military discards it and the idea remains dormant until it finds favor again and the cycle repeats. This is the history of the military glider in a microcosm and the starting point to determine if the Army should rethink the utility of these silent wings for the next millennium

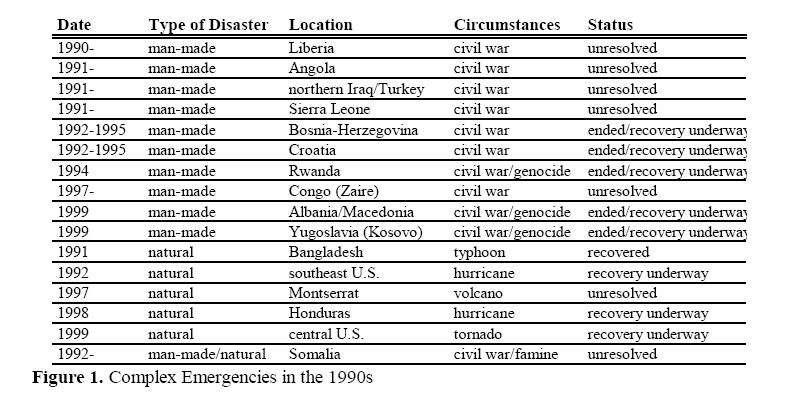

The U.S. Army, like the Reichswehr was, is in a period of transition where the future is uncertain as to how it should wisely invest limited resources to fight the next war. The late Secretary of Defense Les Aspin made

reference to this fact in 1993: "...the dangers of the new era will reinforce the importance of the Army. It will redefine the Army’s missions. And it will require us to reshape the Army so it can respond to those new missions."7 In this decade alone, Army deployments have totaled 33 compared to 10 from 1950 to 1989; the vast majority serving in regions and roles suited towards airborne, air-assault, ranger, and light infantry rather than armored and mechanized operations.8 However, maintenance and fuel costs for shrinking fleets of transport aircraft and helicopters, the

raison d’etre of these elite forces, are expensive and deployments

occasionally time consuming with several simultaneous operations already underway worldwide. Bearing this in mind, it is only logical that the capabilities of the XVIIIth Airborne Corps receive an alternative enhancement since the major combat elements under its command maintain the highest state of alert to meet their assigned operational objective; power projection.

Just as important, to win an active degree of interest by the mainstream and subsequent funding gliders must mirror one or all of the characteristics that are most in demand for equipment suitable for rapid reaction operations in this period of downsizing and reduced budgetary allocations: tactical advantage, multipurpose, simple, cost-effective, a timely initial operational capability

(IOC), and available for procurement by all four services. Traits as these expedites the acquisition process and are factors that weigh heavily on the minds of administrators (and legislators) alike when it comes time to vote on allocations of monies. Thus, procuring gliders makes military and economic sense for several reasons.

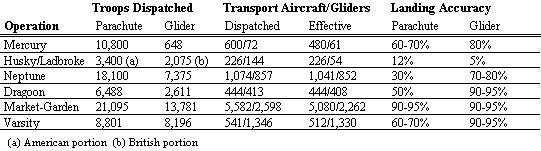

1. Gliders and glider landings dovetail the individual capabilities in airborne (parachute) and air-assault (helicopter) operations while minimizing the associated hazards. While parachute drops embody an atmosphere of surprise and stealth (to a degree), the trade-offs are vulnerability (as airlift assets and descending paratroopers — after a static-line jump from 1,200

feet, are in "double jeopardy" from air defense artillery (ADA)); tactical disorganization (as formations disperse over the drop zone (DZ)); and, firepower (lightly armed, paratroopers are defensively weak). Alternatively, air-assaults integrate tactical organization, precision landings, mobility, heavy payloads, and firepower, while trading-off stealth and surprise (as engines and rotorblades disclose the axis of attack) for vulnerability (to an ambush as troops withdraw or dismount from the pickup or landing zone (LZ). Comparatively speaking, gliders and glider landings prove superior to either

style thanks to several inherent traits.

Stealth and Surprise

Recognized as moments where the greatest weakness of the attacker and of the defender occur simultaneously, the outcome of a vertical envelopment depends on initiative and determination. In a non-permissive environment when an unarmed cargo plane or helicopter approaches and departs from an DZ or LZ is the point at which pilots face the greatest danger of being shot down. Ejecting flares to confuse and divert incoming heat-seeking surface-to-air-missiles (SAMs) is the only countermeasure available to a pilot, provided he has the gear at his disposal, but this method is not 100 percent foolproof. Thus, successful concealment of an airborne formation in transit to the target area can negate

the potential for detection and offset any military imbalances. Stealth is the key determinant in maintaining total surprise. Without the former, one cannot exploit the latter to its fullest potential. Since a glider’s wind-driven propulsion system can maneuver into a gradual or swift descent and has a low metal-content fuselage that does not emit infrared heat its radar signature is negligible. This means it is invulnerable to fixed and man-portable SAMs. Thus, a soundless, low-level glider approach in hostile airspace, especially in a nighttime operation, is liable to inflict a state of paralysis and psychological shock, including paranoia, upon an adversary’s economic, social,

military, and political infrastructure.9

Tactical Organization

Time is of the essence in securing the target area during an airborne assault and minutes can mean the difference between success and failure. Maintaining unit cohesion immediately after landing is therefore essential in bringing its full striking power to bear against a decisive point which may mean fewer casualties and less time mopping up resistance. Luftwaffe Field Marshall Albert Kesselring attributed merit to gliders for adequately filling this requirement: "Gliders, according to their size, hold ten to twenty or even more men, who immediately constitute a unit ready for combat."10

According to one estimate, a glider infantry company could assemble within five minutes of debarkation, thus ensuring its table of organization and equipment, and (what was more important) its chain of command remained intact.11 Parachute insertions cannot make this statement. Any semblance of organization during a parachute drop, dissipates the moment a chalk of paratroopers exits the aircraft. In a best-case scenario, in ideal weather, a company of parachute infantry requires a minimum of 15 minutes to regroup and recover its equipment.12 Factor in hostile ground fire, injuries sustained during the jump, parachutes caught on natural- and man-made obstructions, as well as poor climate, and the reaction time declines further. Night drops lead to further disorientation among parachutists. This is especially true in a worst-case scenario where an airlift undershoots or overshoots the DZ and the cross-winds alter the descent. As a result, a motley collection of units emerges which may find itself involved in a series of disjointed attacks lacking any coordination as dispersed paratroopers search for a friendly face in unfamiliar territory. One need only be reminded of the casualties suffered by the 82nd and 101st Airborne Divisions scattered over the flooded Normandy hedgerows to see the danger. Similar misfortunes continue to occur despite the introduction of the non-steerable T-10 parachute because mass drops increase the chance of midair collisions between jumpers trying to maneuver and land on target. Regarding the Panama City airfield seizure package during Operation JUST CAUSE, the records of the XVIIIth Airborne Corps Historian noted: "Intent of [the 82nd Airborne] Division was to drop 50 meters east of runway, inside perimeter fence. Actual drop was to east, mostly outside perimeter fence in mangrove swamps; also dropped long furthest [landing] was eight kilometers."13

Payload

As a workhorse, gliders served as an immediate force-multiplier for the offensive and defensive firepower for combat units thanks to its payload capacity; an inherent trait necessary for contemporary airborne operations. Credit went to its cost-effective heavy-lift design. By all accounts, Second World War-era gliders adhered to the principle of constructing a simple, yet durable aircraft since most had fuselages constructed of air-tight canvas wrapped around welded steel tubes and honey-combed plywood, "...a

construction technique that provided strength with minimal weight."14 A lack of complicated flight instrumentation and engines meant very little maintenance and kept costs down resulting in a potentially reusable airframe without diminishing, but rather increasing its lift capability. Most models of that era had cargo and troop capacities greater than or equal to every model of transport helicopter (and some cargo

aircraft) currently in Army or Air Force service. Furthermore, the inclusion of hinged cargo doors on either the nose or tail assembly, or both, kept loading and unloading times to a minimum.

Parachute drops and air-assaults, however, require multiple sorties to field enough artillery and prime movers for effective fire missions and adequate mobility. Of the two, air-assault unit guidelines order the dismantling of some vehicle-mounted crew-served weapons into its organic components for overland movement while the squad helicopters to the battlefield to link up with it; a time-consuming process.15 The location of LZs and DZs in high-altitude environments also affect fuel consumption and weight allowance thereby further restricting the quality and quantity of deployable weapons systems by either method. Provided of course, these systems arrive in working order and no equipment mishaps occur such as parachutes failing to deploy or exposure to ground fire while slingloaded beneath a helicopter; The operational account of Operation Just Cause chronicled one such mishap:

Heavy drop carried out...Lost HMMWV [High Mobility Multipurpose Wheeled Vehicle] carrying Stinger SAMs. Damage to two of eight M551 Sheridans [light tanks] from DRB[Division Ready Brigade]-1 company of 3rd Battalion, 73rd Armor: 1) One initially assessed as probable malfunction; was destroyed in drop. 2) One initially assessed as probable parachute problem stuck in mud and destroyed in place when cannot be extracted.16

Other variables can exacerbate similar scenarios such as fierce wind currents altering calculated parachute trajectories and depositing heavy equipment in hostile territory.

Performance

Combat gliders did not yield to the opinion that once an airborne operation was in motion, the entire action necessarily had to unfold according to some predetermined schedule without taking into consideration unforeseen events. A critical assessment of the D-Day airborne landings noted that if tow release occurred at an altitude above 700 feet a pilot could "make a proper approach and come in slow," an option that afforded him the time to select and divert to an alternate LZ if necessary.17 Unlike the sports

glider though, a military glider could not use atmospheric currents or thermals to remain aloft for a considerable amount of time or even be made to climb due to weight, construction, and design. However, it could execute some evasive maneuvers to land on target depending on the method of soaring: gliding or diving flight.18

Perfected by the German Luftwaffe with exceptional results, "dive gliding" produced speeds in excess of 125 miles an hour based upon the angle of descent. If spotted, evading ground fire with this method required deploying a braking parachute and making frequent changes in the diving angle or

spinning for a short time which refutes accusations that gliders were "compact targets." Furthermore, if release occurred at the right altitude, 13,000 feet, a glider could coast to the target area from as far away as 20 miles before going into the dive.19 This radical innovation in tactics is still useful because gliders can execute spot landings in a variety of terrain (including built-up areas) in clearings only yards long.20 Although gliding flight was the accepted standard, after-action reports confirmed that most of the several hundred gliders belonging to a division could

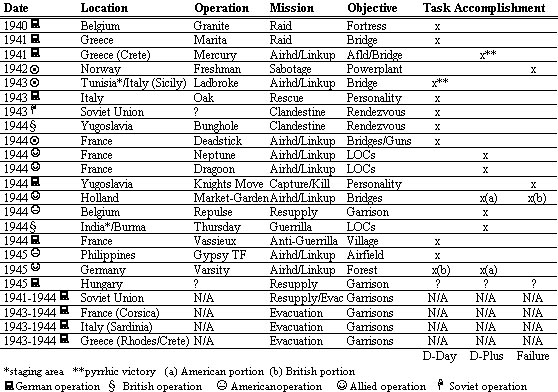

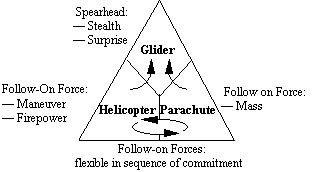

land on target. Figure One denotes a comparison between the success rate of parachute and glider insertion during the Second World War21

Figure 1. Operational performances

of the glider and parachute in combat22

Recyclable

Critics contend that the glider had a life expectancy of only one airborne operation since most assaults left the powerless aircraft destroyed beyond repair or unsalvagable. This statement is true as far as those gliders shot down or that skidded to a halt after hitting natural or man-made obstructions.23 Figure Two below, compiled from the

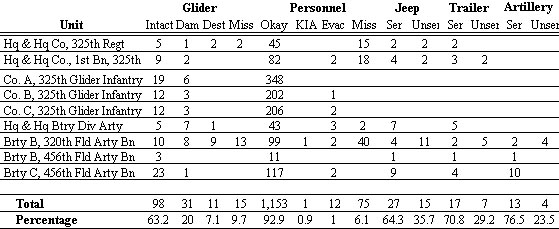

82nd Airborne Division after-action report for Operation MARKET-GARDEN, illustrates most gliders and cargo assigned to individual units landed in serviceable condition, and few casualties were evident.

Figure 2. Landing statistics, 82nd

Airborne Division, Operation Market-Garden24

There were other circumstances, all preventable. First, retrieval of gliders had a low priority due to combat requirements and hundreds sat on secured LZs for several weeks before recovery aircraft or repair teams received permission to enter the area; by then, exposure to the elements had already taken

its toll. Just to give an example, 97 percent of the gliders used by American forces in the Normandy landings were left to rot in narrow pastures in which they landed. Second, limited numbers of qualified recovery crews and pick-up equipment proved insufficient for handling the thousands of gliders involved in a major airborne operation. Third, lax security measures around LZs after an operation led to damage by vandals or theft by civilians who chopped up the plywood fuselages for fuel. Fourth, glider pilots whose job it was to help clear the LZs of spent fuselages and prep them for recovery returned to their staging areas in England, in most cases, three days after landing. Finally, because

of a wartime economy tooled up for mass output, logisticians found it easier to replace than recover used stocks with new inventory taken right from the production line.25

2. Gliders are in a class by itself that units equipped as such would have an edge over their parachute and air-assault counterparts that neither can duplicate for certain reasons.

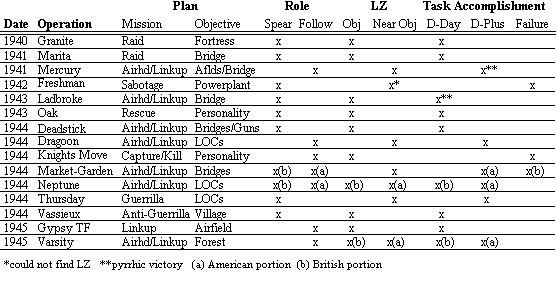

The fuselage is inexpensive to manufacture, meaning an airborne division could contain hundreds of general purpose-, medium-, and heavy-lift versions: a normal wartime complement for a U.S. division boasted 800 to 900 in its order of battle. The availability of sufficient numbers on-hand enabled six infantry and two field artillery battalions plus headquarters and support personnel to

go into battle at once. Contemporary planners with access to similar quantities could earmark enough to sustain training and exercise purposes; provide a replacement pool for losses to normal attrition; and, establish a war reserve to support as many as three successive operations.

Bayonet strength may increase by as much as 30 percent if one factors in the glider pilots whose military occupational specialty (MOS) reverts to that of an infantryman upon landing.

For every hour of operational use, helicopters and transport aircraft require several hours of maintenance and a large pool of technicians to keep them flying. A glider requires fewer man-hours for assembly and routine upkeep: no cumbersome avionics, engines, or extensive wiring exist. Instead,

diagnostic tests and preventative maintenance would stress certifying the structural integrity of the fuselage as airworthy before the next deployment.

Whether in single or tandem tows, pre-stocked and prepositioned gliders in self-deployable theater airborne readiness packages, akin to the POMCUS and Prepositioning Afloat programs, could be effective crisis management tools for accelerating the anticipated deployment schedule of contingency units. Low cost per unit makes this possible. This requires a detailed explanation.

The sole function of transport aircraft and helicopters is to load, shuttle, and unload men and material. With multi-million dollar price tags both cannot loiter for any length of time on the ground as "hangar queens." Thus, neither can serve as a pre-stocked and prepositioned cache for either payload because both are high-priority platforms requisitioned and deployed globally on a

daily basis in a variety of support roles that overtax a finite fleet with a different cargo manifest for each sortie. Bearing this in mind, consider the Herculean effort it takes to deploy one of three DRB’s belonging to the 82nd Airborne from a cold start.

Upon receipt of a notification order, DRB-3, acting in a support role, has 18 hours to "push" Division Ready-Force-1 (DRF-1), one of DRB-1’s three battalion task forces, into the air "chuted up, loaded, and wheels up."26 Task accomplishment in the designated launch

window demands preparation of detailed aircraft movement and loading timetables. These plans must further take into account the transit time for: 1) the arrival of sufficient airlifters from various points of origins; and, 2) DRF-1 to transfer its personnel and equipment from a marshaling area at Fort Bragg, North Carolina for boarding at nearby Pope Air Force Base. Though pre-rigged equipment pallets enhance DRB-1’s readiness, it takes time to properly load an airlifter in a configuration that efficiently makes maximum use of the entire cargo bay. Furthermore, if discrepancies in the flight manifest exist

unforeseen delays may arise and the DRB may not ready be for immediate loading: during JUST CAUSE, "The USAF walked away from earlier planning meetings with the mistaken impression that the 82nd had [only] 25 loads (i.e., five C-141s’ worth) prerigged...In reality, the DRB was loaded in 24 hours, with [the first] plane filled in 10 hours."27

The 101st Air-Assault Division fares no better either since an air-assault DRB is of little military value until the Air Force transports its helicopters to the theater of operations; three to seven helicopters,