UPDATED 12 September 2009

UNITED STATES ARMY POWER PROJECTION IN THE 21st CENTURY: THE CONVENTIONAL AIRBORNE FORCES MUST BE MODERNIZED TO MEET THE ARMY CHIEF OF STAFF'S STRATEGIC FORCE REQUIREMENTS AND THE NATION'S FUTURE THREATS.

UNITED STATES ARMY POWER PROJECTION IN THE 21st CENTURY: THE CONVENTIONAL AIRBORNE FORCES MUST BE MODERNIZED TO MEET THE ARMY CHIEF OF STAFF'S STRATEGIC FORCE REQUIREMENTS AND THE NATION'S FUTURE THREATS.

CHAPTER TWO

THE HISTORY AND EVOLUTION OF AIRBORNE FORCES

"Throughout the ages, effective results in war have rarely been attained unless the approach has had such indirectness as to ensure the opponent's unreadiness to meet it. The indirectness has usually been physical and always psychological."

INTRODUCTION

Through his study of military strategy from the early Greek War to the modern Arab-Israeli Wars, Liddell-Hart identified the "indirect approach" to warfare as the essence of successful military strategy. The speed and depth of an Airborne assault provide both the physical and psychological shock of the indirect approach. This chapter will discuss some of those significant Airborne successes and some failures instrumental in the development of the Airborne warfare concept. First, I will briefly review the evolution of the Airborne from its inception through the military build-up for World War II. Then, in some detail I will discuss the use of Airborne forces by the Germans, Americans and Russians during World War II. Some of the "lessons learned" identified in this chapter will be used to support positions presented later in this thesis.

PRE-WORLD WAR II AIRBORNE HISTORY

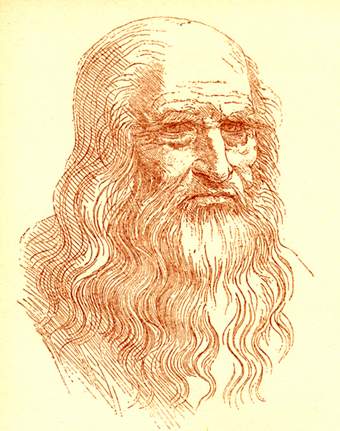

The concept of Airborne warfare has existed for centuries. The Greeks are credited with fables about flying men conducting surprise attacks in the rear of their enemies. The Chinese are believed to have designed a workable parachute, [In 1306, a group of entertainers called the "Acrobats of the Air" demonstrated parachutes from the emperor's palace for a coronation], while Leonardo da Vinci, in the fifteenth century, actually designed and tested a parachute.

http://exn.ca/stories/2000/06/27/56.asp

Da Vinci's parachute - he was right all along

Adrian Nicholas drifts lazily through the air with a parachute based on a 500-year-old sketch by Leonardo da Vinci. Photo courtesy of Heathcliff O'Malley.

By David McCormick, June 27, 2000

In 1483, in the margin of his notebook, Leonardo da Vinci sketched what was probably the world's first parachute. In an accompanying note, he claimed a man using such a device could "jump from any great height whatsoever without injury." [Allegedly] Da Vinci never got to test his parachute, but on Monday, over 500 years later, someone else did. Adrian Nicholas, a British man, proved da Vinci right by successfully skydiving with a parachute based on the Italian's design. "It was time to go," Nicholas says, describing the moment before he jumped. "And I'm thinking 'All right Mr. da Vinci. You promised me it would be safe. I'm trusting you." And we cut it away. And it was very gentle. I was suspended there, hanging in space." Nicholas made the jump with da Vinci's parachute in Mpumalanga, South Africa, where there are wide-open fields and weather ideal for skydiving.The jump was the culmination of three months of work. To build the parachute, Nicholas and his friend Katarina Ollikainen enlisted the help of Martin Kemp, a history professor from Oxford University. Kemp deciphered the 500-year-old note da Vinci left describing the specific dimensions and materials needed to build the parachute. Ollikainen built the parachute, passing up modern tools and materials to use the ones that da Vinci specified in his instructions. Designed primarily of wood and canvas, da Vinci's parachute has a 6.7-square-metre timber frame and weighs 90 kilograms. "All modern understanding suggested that the parachute obviously wouldn't work," Nicholas says. "Nobody said it would work and they gave various reasons why it wouldn't work. And the consensus opinion was that I was going to be in for a very wild ride."

A group of researchers from Salford University in England accompanied Nicholas to South Africa. They're building a simulator of da Vinci's parachute for Manchester's Museum of Science and Industry and decided to tag along. They put cameras and devices to measure speed and movement on da Vinci's parachute.In preparation for the jump, da Vinci's parachute was attached underneath a hot-air balloon, which then took Nicholas and and Ollikainen nearly 3.5 kilometres above the South African countryside. There were two helicopters hovering around the balloon to help film it. Two of Nicholas' friends jumped from one of the helicopters wearing traditional parachutes. Nicholas was attached to the parachute by 15-metre-long ropes. When he was ready to go, Ollikainen cut da Vinci's parachute from the balloon and it drifted slowly away. "From my perspective, I just saw this canvas material billowing in the wind like the sails of an ancient sailing boat," Nicholas says. "And I just hung there in space. There was no oscillation, no rotation or gyration or anything. And I flew for ages and ages and ages. You could see people in the fields all around waving and shouting. It was wonderful. Absolutely wonderful." When Nicholas got within 600 metres of the ground, he cut himself away from da Vinci's parachute and opened a traditional parachute to take him safely to the ground."You don't want to try and land something like that because you can't steer it and there's things about you," he says. "da Vinci never promised that he wouldn't land me in a tree." But despite its lack of a steering mechanism, da Vinci's parachute landed close to Nicholas. And it landed so gently that all the data equipment was still intact. "He was right. Da Vinci was absolutely right," says Nicholas. "Which is quite fun isn't it? I hope we made him smile."

However, it was not until the launching of balloons in the 1780s that the idea of vertical envelopment began to be seriously considered. Napoleon, while massing for the invasion of England, considered the use of balloon to carry his assault troops across the Channel. "One idea was for 2,500 balloons each carrying four men to be launched before the sea invasion, to land in England in a few hours in advance of the main body and cause confusion if not complete surrender."(2)

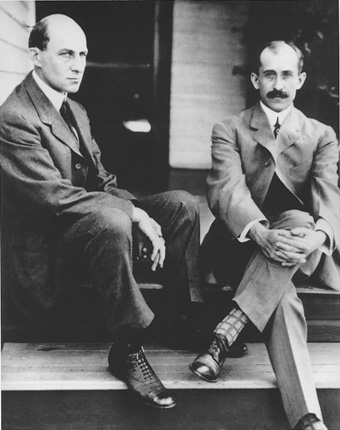

While "balloon-borne" operations failed to materialize, the idea of carrying troops by air would again be considered with the development of the airplane by the U.S. Army which contracted first with the Wright Brothers, who flew powered in 1901.

General John R. Galvin (USA, ret.), writes in Air Assault: The development of Airmobile Warfare, Hawthorne Books, New York, NY, 1969:

"The date was October 17, 1918, less than a month before the armistice. General Jack Pershing had led his forces thorugh the highly successful battle of Saint-Mihiel, in which the American Expeditionary Force (AEF) captured fifteen thousand Germans and 250 artillery pieces in one thirty-six hour period. On that morning Pershing, anxious to get off to the front, which was about five miles north of Verdun, was being delayed by a discussion with his aviation officer, the flamboyant Colonel Billy Mitchell.Pershing wasn't interested in striking enemy's rear with aircraft and he wanted Mitchell to gain air superiority to drive off German aircraft bombing and strafing attacks. After that, Mitchell's pilots should seek out and strike the German troop Concentrations that threatened his forces.

After these missions were accomplished, if Mitchell's pilots had any time left, they should go out and get more information about enemy troop movements along the front. Mitchell quickly agreed to put thtose orders into effect right away, but he was already four or five steops abeyond Perhsing's carefully outlined concept of local air superiority and close air support. He was in fact making long-range plans for the use of his air power and mobility.

By the Spring of 1919, Mithcell assure Pershing the produciton of bombers would be in full swing and there would be enough of them available to support the all-out drive into the heart of Germany, beginning with an attack toward Metz. The Germans had moved strong foreces into position to protect the city, but there was, Mitchell insisted, a way to take Metz without a costly and slow battering ram approach.

For one single massive operation, he would gatehr in all the available aircraft - sixty bomber squadrons consisting of twelve hundred Handley-Pages, Capronis, and de Havillands - and for this mission they would drop not bombs, but parachute troops. In Mitchell's plan, each plane would carry ten men equipped with parachutes and two machine guns; these aircraft, taking off from many airfields, could simultaneously drop a whole division, twelve thousand men, behind the German lines. Imagine, he said, 2,400 machine guns ready to create havoc at a strongpoint in the German rear, while the Allied main attack moved thorugh the crumbling and panicked enemy front lines.

To do the job, Mitchell said he wanted the 1st Infantry Division. He would lift the division into position behind the German lines in one great air armada, with the bombers protected by hundreds of fighter planes flying above, below, and beside the formation. Other pilots, flying at low level all around the position, would disrupt any German counterattacks while the American troops landed, dug in, and prepared themselves. He would keep the strongpoints supplied by air. "It is conceivable that all would not have landed safely, that not every platoon could have been reformed behind those German lines," Mitchell admitted later, "but remember, we should have had a potential strength of 2,400 machine guns. If we could have only got 10 per cent in action against the enemy's rear we should have been successful."

Pershing was skeptical that such an attack could be mounted, but he surprised Mitchell by giving his tentative approval to the general concept. He told Mitchell to go ahead with detailed planning, and to be ready to explain just how it would be done and how the necessary resources would be marshaled and used. In the meantime, said Pershing, he would be happy just to have American control of the air over the expeditionary force.

After Pershing left for his daily tour of the front, Mitchell rushed back to his headquarters to talk to his new operations officer, Major Lewis Brereton. Mitchell excitedly explained that he had sold Pershing on the idea of an air assault behind the German lines at Metz. Now all that remianed was to work out the details and get the airplanes. It would take every every bomber and practically every pursuit aircraft in the Allied fleet, including htose promised from production by spring, but Mitchell was sure that if he could show a workable plan, he would be given the Aircraft.

In the days that followed, Mitchell carried out Pershing's orders to protect the ground troops in day-to-day operations, and at hte same time he kept up the steady pressure to get more bombers into the theater. Brereton made a list of the airfields with range of Metz and figured the maximum number of planes that could be supported by each of them. But while Mitchell bustled through the preparations full of conviction, Brereton could see the problems beginning to multiply. He woudl need more than twelve thousand parachutes, and each man in the 1st Division would have to receive at least rudimentary training in such details as how to use a parachute, how to climb out of the cockpit and launch himself over the side during flight, and how to drop his machine guns by parachute and find them on the ground. Hundreds of bombers from scores of differnet fields would have to come together at rendezvous points and proceed to the target as one large formation. In addition, the troops once on the ground woudl require supplies, which meant more parachutes and more bomber flights. Who would pack the parachutes and supplies after the division jumped? The 1st Division command and control systems would have to be adjusted to allow for the ten-man machine-gun teams that Mitchell envisioned. However, before Bereton could become too deeply involved in attempting to hurdle the many obstacles that confronted him, the armistice stopped his work.

In planning this operation, Mitchell may not have been the first tactician to note the possibilites inherent in the development of troop carrying aircraft (the French had carried out small raids behind the lines as early as the spring of 1918, dropping two-man demolition teams to destroy communications), but Mitchell was the only one who thought in terms of entire army Divisions dropping by parachute.

So although interested, Pershing shelved the plan because it was too novel to risk at that point in the war. Billy Mitchell would have to wait, since the war ended a few weeks later with the Armistice of November 11, 1918. Following the war, Mitchell did conduct a successful experimental airdrop with a small party of parachutists at Kelly Field, Texas but the military authorities were not impressed. The Airborne concept would go undeveloped as the Army sank back to its old ways of planning for the next war with the weapons of the last. (3)

In 1927, Italy became the first country to try practical military parachuting using an improved form of parachute. This new parachute, the Italian "Salvatore," provided a significant technical step forward. Rather than the ripcord type escape parachute used by pilots, the Salavatore parachute was carried on a man's back and deployed through the use of a static line which pulled out the canopy. By 1930, the Italians had several battalions trained in parachuting.

In the 1930s the Soviets took the lead on the development of the Airborne concept. The decade began with an experimental parachute operation conducted on 2 August 1930. On that day, the official birthday of the Soviet Airborne forces, they conducted an exercise near Voronezh. The jump, carried out by a lieutenant and eight men, armed with machine guns and rifles, was a success and ushered in the third dimension of offensive maneuver to modern warfare, the vertical envelopment. Later that year, during maneuvers in the same location, the Soviets dropped an eleven-man detachment into the "enemy rear." The detachment raided a Corps headquarters, captured the Corps commander and escaped back to friendly lines. Following these successful exercises the Soviets mandated the conduct of additional Airborne exercises in an effort to emphasize both their technical and tactical aspects. (5)

These early experiments gave rise to the formation of an experimental aviation detachment in Marshal Tukhachevsky's Leningrad Military District. The unit tested organizational concepts and equipment while working with other ground forces and naval forces. Tukhachevsky, considered the father of the Soviet Airborne, aggressively pursued the development of the Soviet Airborne. He published several articles articulating the role and the missions of the Airborne forces.

Finally, in December 1932, the Revolutionary Military Soviet (Revoensovet) authorized the creation of an Airborne brigade in the Leningrad Military District. Within the next year, the Revoensovet would create an additional 29 Airborne battalions totaling over 10,000 (6) men.

See the early Russian Airborne in action in web page video clips here! AWESOME!

14

In 1935, as part of the Kiev maneuvers, the Soviets demonstrated to the world the air movement of a Division from Moscow to Vladivostok. The 14,000 troops and their equipment were airlanded following the seizure of the airfield by over 1,000 Airborne troops. (7) Subsequent maneuvers, from 1935 to 1937, verified both the utility of the Airborne forces and the doctrinal concepts for their use. The Moscow exercise of 1936 involved the airdrop of over 5,000 Airborne troops to secure an airfield with the follow-on airlanding of the 84th Rifle Division. Although, the Soviet Airborne forces continued to increase in size, adding two new Airborne brigades in 1936 and four more in 1938, Stalin's brutal purges of the late 1930s crippled the further development of the doctrine and the refinement of the Airborne techniques.(8)

[Note how narrow-minded tyrants (Hitler, Stalin) oppose empowering others via Airborne forces which require initiative and granting of dignity and respect to the Paratroopers vice robotics]

The Western world had military observers at many of the Soviets' major maneuvers, including the 1935 Kiev maneuvers and the 1936 Moscow exercise. The Soviets even produced a public relations film on Airborne operations.(9) Yet, the West's initial interest in the Airborne dimension of warfare soon died down thanks to a combination of ill-considered indifference and a growing preoccupation with more urgent matters. Most European countries were overwhelmed with the substantial effort required to raise a modern army in response to the growing German threat. They had no resources to spare on the production of transport aircraft and specially trained Airborne troops for what seemed to be untried ideas. (10)

[Editor: Sounds like today's whining excuses = why then does author propose such expenditures today on an air-droppable 11-ton AFV when we already have one in the M113A3?]

By the late 1930s, American military students were aware of the developments in Airborne operations and studied the problems of Airborne warfare at the U.S. Army Command and General Staff College.

But in Washington, Airborne operations were still considered "fluff" and no serious attention was paid to the development of an American Airborne force, (11)

Unlike the rest of the Western world, the Germans energetically took up the idea of Airborne warfare as a complement to the armored thrusts of the blitzkrieg style of warfare. Germany was well aware of the Russian experiments with Airborne troops and followed them closely with the help of secret military agreements they made with Russia in 1922. (12) The idea of Airborne warfare suited the German philosophy of that time. Surrounded by enemies, determined to strike the first blow and cognizant of the value of surprise in destroying the enemy's morale, Airborne warfare seemed tailor made for the blitzkrieg. Additionally, the groundwork for the airlift support of Airborne warfare was already laid. Since 1928, the German airline, Lufthansa had been buying aircraft which could be utilized as transports in a time of war. By 1935, over 250 of the aircraft were available. These aircraft provided the needed airlift to make the German Airborne a viable force in the coming war. (13)

THE GERMAN WORLD WAR II EXPERIENCE

The Germans were the first to use Airborne forces in major combat operations. As a result of their keen interest in this new approach to warfare and the Russian stagnation that accompanied their purges, by the late 1930s the Germans had taken the lead in the development of Airborne forces. Under the command of Major-General Kurt Student, the German Airborne forces, the 7th Flieger and the 22d Infantry Divisions, prepared for war. Although the German Airborne forces were ready to deploy in Czechoslovakia in 1938 and Poland in 1939, they were not used. [Editor: Not correct. German Paratroopers were dropped behind the heavily defended Czech line near the town of Bruntal in a live-fire TRAINING exercise as the Czech government gave up ground to the Germans without a fight.] So, when Hitler told General Student to prepare for Airborne operations on the

Western Front, General Student was determined to see that the Airborne forces would play a major part in the upcoming operations. (14) It was 9 April 1940, when Hitler finally unleashed the Airborne "weapon" on the Allies. The invasion of Denmark and Norway depended heavily on surprise, a surprise only possible with the use of Airborne forces. A single Airborne battalion captured four separate airfields and a key road bridge, providing the security needed for the build up of follow-on forces. Within two hours, the Luftwaffe was operating from the captured runways and establishing forward fighter bases, while airlanded troops built up a force large enough to compel the surrender of the two countries. For the Allies there was grave concern. Never before had an enemy moved so far, so fast and so deep into friendly territory without warning. (15) For the Germans, despite the success of the Scandinavian campaign, the Airborne still had to prove itself. The assault on the prepared defenses of the Western Front would be their first "real" test.

Unfortunately for General Student and the German Airborne forces, Germany's use of Airborne forces in the Scandinavian campaign forewarned the Dutch of what to expect and they altered their deployment accordingly. On 10 May 1940, the German Airborne forces that tried to seize the airfields around The Hague, were met with heavy fire. The defenders were ready and the parachutists were quickly rounded up. As the airlanded units came in to land they were decimated. All over the Hague area there were smoking aircraft wrecks; the Dutch were triumphant, but also bewildered and nervous. South of The Hague, the 7 Flieger Division fared much better, mostly because it was not dependent on the landing of aircraft to get troops on the ground. The German Airborne forces in the south seized a number of airfields, several key bridges (intact), and the "impregnable" Belgian fortress of Fort Eban-Emael. These objectives were critical to the success of the

German "blitzkrieg" across the low countries. The neutralization of the Belgian Fort Eben-Emael by the German Airborne forces provides an excellent example of their effectiveness. Fort Eban-Emael, a large underground fort dominating three well defended bridges over the Albert Canal, was manned by over 1,200 Soldiers. A 400-man strong glider force silently attacked at dawn with nine gliders (78 men) landing on top of the fort. Using hollow-charge explosives, they blasted their way through the roofs of the gun emplacements and quickly disabled the guns. With the guns out, the remainder of the force was able to quickly secure two of the three critical bridges over the canal. The German armored forces were then able to cross the heavily fortified Belgian border without a fight, in a matter of hours. (16) The Airborne operations in the West were not only tactically successful, but also operationally successful. The very fact that large forces could penetrate deep behind the Dutch defenses, undoubtedly broke the resistance of the Dutch and saved the German Army the cost of a serious fight in capturing Holland. (17) Holland surrendered in four days.

Germany's successful Airborne invasion of the island of Crete in May of 1941 ushered in a new era of conventional warfare. More than 22,000 men and 1,450 aircraft were used by the invading Germans in the first battle to be fought without traditional land or sea augmentation. (18) The German plan was fairly complicated. General Student planned to conduct several airdrops creating a number of small airheads, at first without any definite point of main effort, and then expanding the airheads until they ran together. This technique was to come to be called "oil spot tactics."

The four "oil spots" on Crete were the airfields at Maleme, Retimo, Herakleion and Canea. (19) The objectives were well defended [Editor: Ultra Secret revealed to Allies exactly WHERE the Germans were landing] and the 4,300 German Paratroops suffered heavy casualties. By nightfall on

the first day, none of the airfields were secured and the four German Airborne regiments were surrounded and under considerable pressure. The next morning General Student sent into Maleme the reserve Airborne battalion and was still unable to gain control of the airfield. In desperation he started the airland operations at Maleme even though the airfield was only partially controlled and still under British fire.

[Editor: not totally correct read the links we provide for a detailed account of the Battle for Crete]

This tipped the balance in his favor and the airfield was finally secured. The remainder of the 5th Mountain Division airlanded at Maleme and the Germans gradually rolled up the island from west to east. British casualties totaled 17,325 while the Germans lost 5,678, mostly Paratroopers who dropped in on the first day.20 Although costly, the Airborne assault of Crete demonstrated, as no other campaign had, the full effectiveness of Airborne warfare.

[Editor: remember there was no surprise on Crete thanks to the Allies being able to intercept and decode German transmissions]

The heavy losses at Crete spelled the end for the German Paratroopers. General Student lamented that

"Crete was the grave of the German Paratroopers"

and Hitler said,

"after Crete, we shall never do another Airborne operation. . . . The day of the Paratrooper is over." (21)

[Right Bavarian Corporal. Several battles and wars won since then by the Paratrooper show that the day of the narrow-minded tyrant-&*%shole is what is over]

It is ironic that the operation that ended the German Airborne operations, motivated both the British and the Americans to devote considerable energy into the development of their fledgling Airborne forces. While the success of the German Airborne at Fort Eban-Emael got the American General Staff's attention;

"Crete was the absolute proof of the efficiency of Airborne operations." (22).

[Of course, silly we knew where they were landing and STILL COULDN'T STOP THEM.]

RETURN TO AIRBORNE WARFARE CONTENTS PAGE