Lessons Learned: Put the "Mountain" Back in the 10th Mountain Division

PROBLEMS

AUTHORS NOTE: We know its easy to criticize and SOF certainly doesn't want to appear to be a Monday-morning quarterback. However, information from U.S. forces at Kandahar and Bagram Air Fields tells us that Operation ANACONDA mission planners violated just about every rule of the tactics manuals: underestimating the enemy's strength and capabilities, over-reliance on air power for support, transport, and resupply in a high-mountain environment, lack of adequate preparatory and supporting fires, separation of forces, lack of mutual support between units well, the list is extensive. As you'll see in this article the entire operation seemed in danger of failure from the moment the troops loaded the helicopters. It was only the determination and professionalism of the troops on the ground and the leadership at the lower echelons that salvaged something from a flawed plan. It is disturbing to SOF that the mission planners had to re-learn fundamental tactical lessons. Company-grade and junior field-grade officers (the guys who bite the bullet down in the platoons, companies, and battalions when the colonels and generals screw- up) would have good reason to be very critical of some of their commanders and especially the mission planners at Division-and Brigade-level. Unfortunately, eight U.S. servicemen died and more than 40 were wounded executing a plan that initially just didnt work. The author, long-known by SOF, has assumed a nom de guerre to protect his sources.

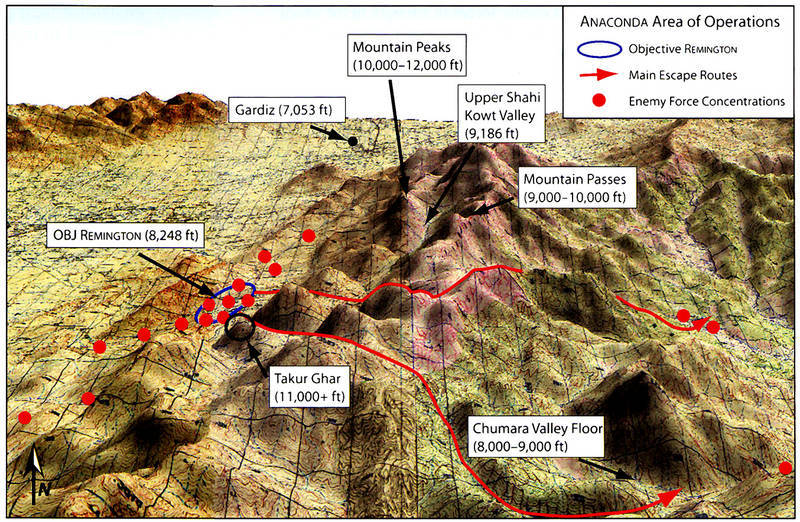

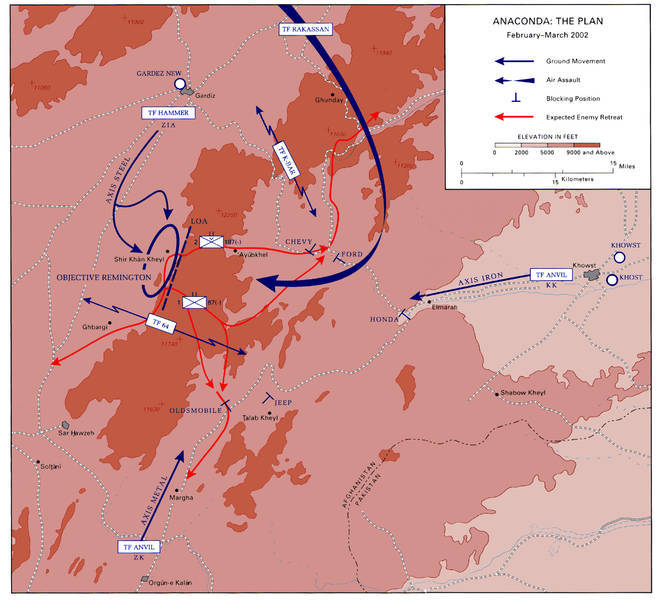

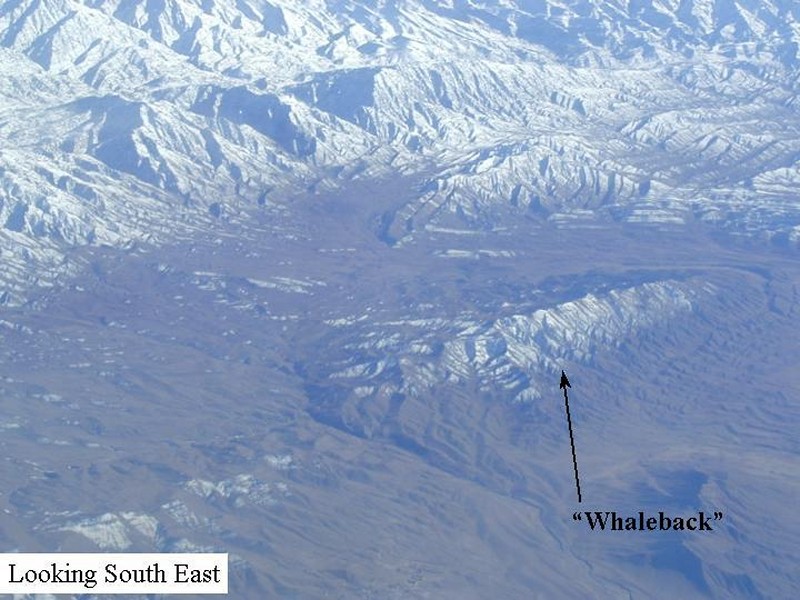

The mission of OP ANACONDA was to destroy the last identified concentration of al-Qaeda and Taliban troops in Eastern Afghanistan. Intelligence indicated that several hundred enemy had gathered around the town of Sherkankel in the Shah-i-Kot Valley, an extremely mountainous region (Hindu Kush mountain range) immediately west of the Afghanistan/Pakistan border. The operational area contained the town of Sherkankel in the valley, with a 10,000-foot feature dubbed the Whale's Back on the west side of the valley, and the 10,000-to-12,000-foot Shah-i-Kot mountain range on the East side. Intelligence based on overhead imagery and strategic reconnaissance (Special

Operations Forces) indicated that the enemy were located in the valley in and around the town of Sherkankel.

Based on this intelligence, an operations plan was issued ordering two U.S. battalions (2nd Battalion, 3rd Brigade, 101st Airborne Division and 1st

Battalion, 2nd Brigade, 10th Mountain Division) to conduct an air assault to occupy blocking positions in the Shah-i-Kot mountain passes and seal-off the enemy's escape routes east from the valley towards Pakistan. Once the blocking positions were established, an Afghan force advised and supported by special operations forces would sweep south down the valley into Sherkankel, and drive the enemy east towards the U.S. battalions holding the high ground: a classic hammer-anvil plan of attack. Unfortunately, it fell apart almost immediately.

The U.S. intelligence estimates of the enemy's strength, capabilities and locations in the Shah-i-Kot Valley were inaccurate. Perceived rag-tag remnants numbering in the several hundreds were actually about 1,000 determined and well-equipped al-Qaeda and Taliban fighters many of them foreigners (Chechens, Uzbeks, Arabs, Pakistanis) with nothing to lose. Furthermore, the main enemy positions werent in the valley town of Sherkankel they were dug into caves and rock bunkers (sangars) along the ridgelines of the Whale's Back and the Shah-i-Kot mountain range, both of which overlooked the valley from the high ground in a classic horse-shoe defense exactly where any novice tactician would have surmised the enemy would be located (especially based on the historical precedence of basic Afghan tactics).

Looked Good On Paper

The blocking battalions had to land on the forward slopes of the Shah-i-Kot mountain range because there were no better helicopter Landing Zones (LZs). This exposed the helicopters and their cargo of infantrymen to direct observation and fire from the Whale's Back, the town of Sherkankel, and the top of the Shah-i-Kot range itself. The planners of this mission expected the troops to move uphill into their blocking positions while in full view of the enemy. Only two LZs were used one at the north end of the Shah-i-Kot range for the 2nd Bn, 3rd Bde, 101st Airborne and the other at the south end for the 1st Bn, 2nd Bde, 10th Mountain. The two LZs were separated by about 8 kilometers of steep, rocky, mountain ridgeline. If either battalion ran into trouble on their LZ there would be little, if any, chance of link-up or mutual support. Who came up with this brilliant scheme of maneuver?

To avoid collateral damage and maintain the element of surprise, there would be no prior bombardment of the (incorrectly) identified enemy positions. Instead, the air assault would go in cold. Not a good idea. When did they start teaching this at Fort Benning or Command and General Staff College? Nor

would units deploy their battalion mortars for indirect fire support. No problem, said the head-shed, we've got eight Apache attack helicopters and Close-Air Support (CAS) for fire support. The operations order called for complete dependence on air assets for all fire support. The helicopters, at the limit of their operational ceiling, were flying in mountains with the possibility of imminent bad weather.

These fundamental planning and tactical errors alone paint a different

picture of Operation ANACONDA than the Pentagon briefers and General Tommy Franks have given the public.

On Day 1 of the operation, helicopters approached the LZs in the late

afternoon. There were no preparatory fires or airstrikes on the LZs. Upon landing on the two LZs on the exposed slope of the Shah-i-Kot ridge, they came under immediate and intense enemy fire from prepared defensive positions sited above and all around them. Incoming fire consisted of everything from small arms to mortars and heavy machine guns, firing with interlocking arcs from both the top of the Shah-i-Kot and across the valley from the Whale's Back. The Apache attack helicopters attempted to suppress the numerous enemy positions and four of the eight were immediately damaged by RPG and machine-gun fire. The damaged aircraft flew back to the Forward Operating Base (FOB) at Bagram Airfield (north of Kabul) an hour away. So much for direct-fire support from aviation in Afghanistan. This is something the Soviets learned the hard way and Major General Frank Hagenbeck should have learned the easy way by studying the Soviet lessons learned. Didn't anyone read about the Air Cav in Vietnam?

Both battalions managed to land on their respective LZs, in the low ground, thus exposed to direct- and indirect-fire from the surrounding enemy positions on the high ground. The 2nd Bn, 3rd Bde, 101st Airborne secured

their initial objective at the north end of the Shah-i-Kot ridgeline, but continued to take enemy fire from the Whale's Back across the valley, pinning them down. They couldn't move south down the ridgeline to their assigned blocking positions. The 1st Bn, 2nd Bde, 10th Mountain on the southern LZ had

a tougher time. One of their Chinook helicopters was hit and crash-landed near the 2nd Bn, 3rd Bde, 101st Airbornes LZ. Pinned down in their LZ by

enemy fire, the battalion from the 10th Mountain declared its LZ "untenable" and requested extraction. They occupied the LZ in a defensive perimeter under heavy enemy fire throughout the night and were extracted the next morning back to the FOB.

Day 1 was a failure, plain and simple. Neither battalion had occupied its blocking positions. The anvil was not in position. The enemy escape routes east through the Shah-i-Kot range to Pakistan were wide open. In addition to the four damaged Apaches and a crashed Chinook, a second Chinook was shot down at the southern LZ; eight Americans were killed in action and another 40

or so wounded. The weather turned bad, negatively impacting air support for the next 24 hours. As one infantry officer involved in the operation sarcastically remarked, "Bad weather in the mountains? Who would have expected that?" The Allied Afghan movement-to-contact, south down the valley into Sherkankel, went awry when they took heavy small-arms fire from the village, suffered about 30 casualties, and immediately retreated. For approximately the next 48 hours, Operation ANACONDA ceased, as Brigade and Divisional commanders and operations officers attempted to salvage what appeared to be a complete disaster.

Grunts Save The Op, But Planners Lose The Enemy

When the weather cleared the mission planners reverted to their default solution: Airpower will save the day. For approximately the next 24 hours U.S. airpower carpet-bombed enemy positions on the Whale's Back and all along the Shah-i-Kot mountain range with everything in the U.S. arsenal short of cruise missiles. Eventually, it was decided to use the battalion position on the north end of the Shah-i-Kot range as a firm base, push south down the ridgeline to clear out the enemy positions, and try to occupy the original blocking positions. The reconstituted battalion from the 10th Mountain Division and a second battalion from 3rd Brigade of the 101st Airborne Division were flown into what was termed the "firm base", and started an advance down the mountain range assisted by heavy-air and attack-helicopter support.

Massive air support suppressing remaining enemy positions on the Whale's Back across the valley, and the personal efforts of the infantrymen on the ground in those maneuver battalions, overcame poor planning and organization and got the job done. While the two infantry battalions were seizing their original objectives, the Afghan forces, rallied by their SF advisors, took the town of Sherkankel. Of course, the hammer and anvil were too late.

Rather than sit still for a week and await certain defeat in a battle plan implemented days before, most of the enemy had withdrawn east across the Pakistani border. A small rear guard remained to delay. The blocking positions eventually occupied by the three U.S. infantry battalions didn't block anything the enemy was gone.

Observers on the ground, all infantry officers, say the air assault on Day 1 by 2nd Bn, 3rd Bde, 101st Airborne, and 1st Bn, 2nd Bde, 10th Mountain did not go well. According to one field-grade officer, To be brutally honest, the enemy gave them quite a spanking. I have to tell you, as the first reports of casualties and downed helicopters were coming back to us from the initial assault, all everyone could think about was Blackhawk Down! It looked that bad.

On 9 March, a week after Operation ANACONDA commenced, a Canadian battle group, the 3rd Princess Patricias Canadian Light Infantry (3 PPCLI), opconned to the 3rd Bde Rakassans 101st Airborne, received orders to join 2nd Brigade 10th Mountain Division for combat operations as part of OP ANACONDA. The 3 PPCLI was ordered to clear the Whale's Back mountain on the Western side of the Shah-i-Kot Valley of an estimated 60-100 enemy holdouts dug-in or hiding in caves, and then conduct Sensitive Site Exploitation (SSE), i.e. searches of all caves and enemy fighting positions. The SSE tasking meant a detailed sweep over a linear mountain ranging in elevation from 6,500 feet (at the base) to 10,000 feet at the spine; that is, 7 kilometers long and 2 kilometers wide. The final phase of Operation ANACONDA was to sweep the Whale's Back was named Operation HARPOON.

The 3PPCLI launched a battalion-strength air assault against the Whale's Back shortly after first light (0730 hours local time) on 13 March, inserting via

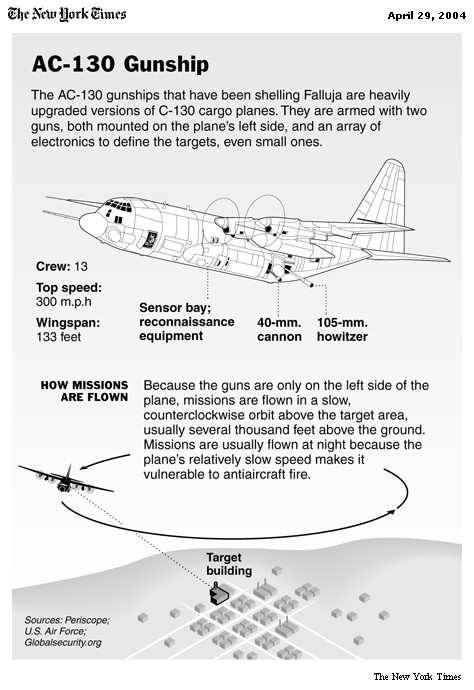

CH-47 Chinook helicopter into a single-ship LZ at the northern end of the mountain. USMC Super Cobra attack helicopters, AC-130 Spectre gunships, and Predator unmanned surveillance aircraft provided close air support. F-18 Hornet and A-10 Warthog jets were available on stand-by. B-52s

conducted round-the-clock carpet-bombing of suspected enemy positions on the eastern side of the valley.

Whither Close Air Support?

A-10s do not have legal authorization to drop jellied gasoline aka ("napalm") anymore to reach out into the rocks and crags where enemies hide like we used to do in previous wars. We don't even have aircraft that can deliver non-lethal smokescreens to temporarily shield our landing forces from enemy fires. What ordnance we can bring to bear is not directed by an Airborne Forward Air Control (AFAC) plane like we used to have with enlisted Army observers...

There were few enemy left on the Whale's Back, and the aggressive Canadians promptly engaged them with anti-tank rockets and small-arms fire, killing three. Moving tactically at 10,000 feet with full combat loads through mountain terrain, it was fortunate that the Canadians were veterans of cold-weather and mountain training. They spent five days clearing enemy positions and searching more than 30 caves; a dangerous business fraught with booby-traps, mines, and possible ambushes on the Whale's Back. They found large caches of ammunition and equipment, collected intelligence documents and maps, and searched a few dead al-Qaeda killed in the airstrikes.

The Canadian infantrymen were extracted by helicopter on 17 and 18 March bringing Operation ANACONDA/Operation HARPOON to a close.

In light of the self-congratulatory pronouncements made by Major General Hagenbeck, General Franks, and others, its doubtful the full extent of the ineptitude at Division- and Brigade-levels will ever be exposed fully (unless one of the battalion commanders retires and writes his memoirs). The failure to fully disclose the operations shortcomings and the predilection of the senior leadership to paint a rosy picture of a great success has impacted morale only slightly. The troops, NCOs, and lower-ranking officers are used to such posturing and cover-ups by the upper echelons. Given the obvious tactical blunders and poor planning, Operation ANACONDA was a failure. Was it a complete failure? Maybe not, but neither was it an unqualified success.

It was inevitable that some enemy would escape, but hundreds were KIA by airpower over the eight-day bombing operation, while the infantry battalions were trying to fight their way south along the eastern ridgeline of the Shah-i-Kot to secure the blocking positions. The enemys combat power in the region and his stockpile of arms was destroyed. The enemy personnel that escaped were stragglers and small groups of disorganized survivors forced to abandon most of their heavy weapons.

As one squad leader has said, "We didn't get em all, but we messed em up good."

Cincinnatus is a former U.S. Army infantry officer with experience on battalion and brigade staffs, and experience in Afghanistan.

www.spectator.co.uk/spectator/thisweek/9887/we-dont-do-mountains.thtml

"We don't do mountains": British officers will not criticise the U.S. forces, but, discovers Julian Manyon, the GIs are full of surprises

Bagram airbase, Afghanistan

It is often by accident that one makes the most surprising discoveries. I was driving with 'Bud', a slightly pudgy American Soldier, through the Bagram airbase, now transformed from derelict battlefield into the

sprawling headquarters of the U.S. Army in Afghanistan. All around us baggy-uniformed troops queued at meal tents or whizzed past in oversized jeeps and vehicles that looked like militarised golf carts. Massively muscled Special Forces troops in designer sunglasses manned a heavy machine gun in front of the PX, while ferocious-looking female Soldiers with the build of prop forwards and carrying grenade launchers guarded the runway. Beside me, Bud grazed continuously on the half-empty packets of barbecue-flavour crisps and honey-roasted peanuts which littered his vehicle. On his shoulder he wore a patch which said "Mountain", the emblem of the 10th Mountain Division, one of the first American units sent to this extremely mountainous country. So to make conversation, I inquired about his mountain-warfare training. "No sir, we don't do that", Bud declared in a masticatory pause. "We don't do mountains".

I thought my hearing must be at fault, so I asked the question again but received the same reply. The 10th Mountain Division is based at Syracuse, New York, he told me, and normally never goes anywhere near mountains. Still doubting this startling intelligence about a unit which has been described in both the American and the British press as mountain-warfare specialists, I sought out their press officer who confirmed that Bud's account was correct.

U.S. over-reliance on airstrike Firepower

The division takes its name from a second world war unit that did 'do' mountains, but such training was discontinued years ago. 'We've had a lot of practice recently, though,' the press officer told me brightly. Indeed they have. Troops from the Mountain Division bore much of the brunt of the recent Operation ANACONDA, in which, despite awesome U.S. firepower, the assault troops ran into trouble on the ground. More than half the 47 wounded suffered by the Americans were from the 10th Mountain (the eight

who died were all Special Forces) and, according to one officer, troops

ferried by helicopter to a high ridge had to sit down for half-an-hour before they could move in the thin air. For all the media hoopla, ANACONDA failed to encircle and crush the Islamic diehards who still infest the mountain region straddling the Pakistan border, and who appear to nourish hopes of mounting a long-term guerrilla war.

All this at least explains why the Pentagon is happy to see our Royal Marine Commandos shoulder some of the burden. Despite debate in the British press over whether our boys have trained at high enough altitudes for a country in which the grandest peaks reach almost 25,000 feet compared with 15,000 feet in the Alps, there can be no doubt that they do "do" mountains. Physically, the contrast between the British and the American troops is subtle but striking. The men of the 10th Mountain are often big and seem more or less fit, but to my eye at least they lack the honed edge of real combat troops. The marines, by contrast, are sometimes smaller men, but they have the rugged, self-confident sturdiness that speaks of months of training in the most demanding conditions, and they carry their weapons as if they mean business [Editor: infantry weapons will need to win the fight not firepower from someone else ie; air strikes].

British officers are at pains to cast no aspersions on the fighting qualities of the American ally they have come to assist, though they do hint at a slightly different tactical approach. U.S. bombing is lauded for its power and high-tech "accuracy". One British officer grinned with what appeared to be a certain relish as he told me that the Americans could, if required, land a bomb on the exact spot where I was standing next to my vehicle. But asked if the British troops will follow American doctrine and mount their assaults only after saturation bombing, the answer appeared to be no.

Maneuver needed to locate and destroy elusive enemies in mountainous terrain

"Remember Malaya," said the officer. "What we did there seemed to work, and Northern Ireland too. We have a great tradition in this sort of warfare". He was sphinx-like on detail but the reference appeared to be to the careful collection of intelligence among the local population allied with tactical surprise. Not far away RAF mechanics were working on the small fleet of Chinook helicopters that will ferry the Royal Marines into combat. They tested mysterious attachments designed to neutralise enemy missiles, while the pilots waited to practise the low-flying skills on which many operations will depend.

A long period of cat-and-mouse in the Afghan mountains may well be required: both the future of the country and the final balance-sheet of this campaign against terrorism remain to be defined. The Taleban have been swept from power but still seem to command a residual loyalty in some Pushtun areas. Indeed, the graves of some of the Taleban fighters who died in Operation ANACONDA have been turned into a local shrine. And what was once the all-important objective of mounting Osama bin Laden's head on a pole is these days scarcely mentioned.

But, without that sort of symbolic success, resistance by Taleban and al-Qa'eda ultras may persist and even grow, while there remain strong doubts about the ability of the warlord-riven interim government, or whatever succeeds it, to control a unified country. The Americans can take some satisfaction in their choice of interim Afghan leader, Hamid Karzai, who cuts a plausible, even sympathetic, figure. But one only has to look to either side of him at the hardened, cynical faces of some of his Northern Alliance ministers to see the mafiotic influences that are still doing their best to pull the strings.

After the recent earthquake in northern Afghanistan, while international aid workers appealed for helicopters to carry out the injured, Afghan military commanders were touting their aircraft to foreign journalists, offering trips to the disaster area for thousands of dollars a time. Meanwhile, the efforts to form a national army - or, to give its preferred title, a National Guard - has run into some telling difficulties. By the time this article appears, the first 600-strong battalion of this force will have held its passing-out parade after weeks of intensive training by British troops from the Isaf peacekeeping force. But, according to an Afghan source who has been closely involved in the training programme, substantial numbers of them intend to quit the ranks as soon as they have graduated. "Why should I stay in this army?" my source reported one of them as saying. "Back home I am a commander. I have cars, I have businesses and 100 men who follow me. I wouldn't stay in this army if you paid me thousands of dollars a week."

The difficulties appear to stem from the feudal anarchy of Afghanistan and, in particular, from the methods by which the 600 were selected. For reasons that are not entirely clear, the Afghan ministry of defence, which was responsible for recruitment, spread the word among its forces that the 600 would be flown to Britain for training. Such was the allure of this idea that many local commanders - leaders of the countless armed bands which make up the pro-government forces - decided to reserve this plum assignment for themselves. The commanders duly assembled in Kabul, only to be told that it had always been Isaf's intention to train them in the Afghan capital. There was further dismay when the men realised that British military training does not include the languid lunches and long naps normally enjoyed by the Afghan condottieri but involves repeated drill and such unpleasantnesses as crawling on one's stomach under barbed wire. According to my source, disciplinary problems were resolved skilfully and effectively by the British trainers, and the Afghans decided to stay the course 'because otherwise we will be seen as failures in our villages'. But it remains to be seen if Isaf has created the core of an effective national army or merely a better class of cut-throat.

Meanwhile, I have been able to contemplate the recent, tragic history of Afghanistan from the comfort of a former Soviet army interrogation centre now converted by an enterprising businessman into a somewhat eccentric guesthouse. The Hotel Mustafa in Kabul boasts bars on all doors and windows, and barred partitions, fortunately left open, in the corridor to the shared toilet. Who knows what atrocities took place here, though with the spring sunshine streaming through the bars it is an oddly cheerful place, and I may even miss it when I move to a tent in the alternate mud and dust of Bagram to await the start of British military operations.

Julian Manyon is Asia correspondent of ITV News. This article is also reproduced for ITV News online and can be seen in 'Location reports' at www.itv.com/news

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Soldiers_for_the_Truth_Foundation

ANACONDA: Absolute Success, or Wake-Up Call?

By Gary R. Stahlhut

Now that the dust has settled with regards to Operation ANACONDA, I believe this is the time to start writing a truthful and detailed after operations report. Since I was not directly involved in this operation I can only write about what I have observed, read about, or been told

happened. We cannot only rely on official reports of the operation, since the information was controlled and censored, thus making it imperative to produce accurate and honest appraisals of what happened to our troops, especially AARs from the 10th Mountain Division. The conclusions derived from the lessons learned during this operation must be used to improve our training and our command and control procedures.

Operation Ananconda was designed to encircle and destroy Al Qaeda and Taliban troops who had been infiltrating in to the caves and valleys of the mountainous region of Shah e Tot. Much like the mountainous area of Tora Bora, this region was also being used to store weapons and hide enemy troops in a multitude of caves and tunnels built into the mountains.

Operation ANACONDA incorporated the use of blocking forces to avoid repeating the mistake of leaving the back door open, as happened during the Tora Bora campaign when most of the Al Qaeda and Taliban fighters infiltrated out of the area before being captured or killed. Operation

ANACONDA was fought by 1,500 Soldiers at altitudes of 10,000 feet and more, making this operation one of the highest altitudes at which U.S. combat forces have fought in since World War II. Infantry from the 101st

Airborne Division, 10th Mountain Division, U.S. Special Forces, and Afghan allies fought gut-busting infantry combat which has not been seen since the war in Vietnam.

Operation ANACONDA required infantry to pack in what they needed to fight and survive, the use of helicopters was very limited in the mountains due to the altitude and amount of ground fire thrown up against them.

The high altitude caused immense problems for the men of 10th Mountain Division, which, despite its name, is not trained for mountain warfare. Many Soldiers suffered from altitude sickness, cold weather exposure,

muscle failure, and weapons failures. To be fair, despite the 10th Mountain Division's best efforts, they were not trained or prepared to fight a prolonged mountain campaign. While division elements had earlier

seen combat most notably in support of the 1993 Task Force Ranger relief in Mogadishu, most of the division's missions of the past decade were in support of peacekeeping missions in Kuwait, Haiti and Bosnia.

I believe that the results of Operation ANACONDA give strong support to actually make the 10th Mountain Division, a true Mountain Division. The "Mountain" tab should be a qualification tab, not just another [unit] shoulder tab. Each Soldier should go through a mountain school (much like Ranger School) and be awarded the tab only if they graduate, to be able to serve in the division. This includes the division support troops. Operation ANACONDA will certainly not be the last time we will have to fight an enemy in mountainous terrain.

The war in Afghanistan is fast becoming a guerilla war, which cannot be

measured by declaring each military operation an absolute success or by how many enemy we kill. Reporting estimates of enemy dead makes good headlines, but as we found out in Vietnam, our enemies are not only willing to sacrifice themselves in battle against us, their strategy is also to outlast our will to continue to fight them.

Success in a guerilla war is not won by any one battle or military operation. Guerillas will seldom welcome pitched battles against a superior enemy, but will use tactics that minimize the superiority of their enemy and maximize their own strengths. They will strike when they can achieve surprise, achieve a tactical advantage and inflict as much damage as possible before retreating from the area before their enemy can react against them. The guerilla will use hostile terrain against us, including jungles, mountains and urban areas. The battles in Somalia almost a decade ago, the battles we have recently fought in Afghanistan and the Israeli punitive actions in Palestinian West Bank cities are a testament to the wars of the future.

Success at beating the guerilla was is not measured by how many of them are killed, it is ultimately crushing the guerilla's ability to sustain and wage a war without having any impact of the government, or the people who live in the area of the insurgency. This takes time and it also takes the will to fight the guerilla until he is defeated.

This is why I do not agree with the initial Pentagon and press assessment that Operation ANACONDA was the success it has been portrayed to be. As enamored as we tend to be with our superior technology and firepower, we completely underestimated the size of the enemy force at Shah e Tot and their tenacity to fight, even when confronted by our overwhelming firepower.

As far as I am concerned, reports of the use of the use of 2,000-pound "thermobaric bombs," (designed to deprive caves of oxygen) and many hundreds of smart bombs, were over shadowed by the ability of the Al Qaeda-Taliban ability to severely damage all the AH-64 Apache helicopter gunships involved in the battle and to pin down large numbers of our troops.

Operation ANACONDA not only identified our overconfidence in the effectiveness of airpower and technology to break the enemy's will to fight, but it also showed our own short-sightedness to believe that the Al-Qaeda-Taliban forces would not be prepared to escape and evade the trap we had set for them.

The fact still remains that no matter how many bombs (smart or dumb) we

drop, no matter how many Apache gunships or Predator UAVs we use, the outcome of these battles will still come down to the ability of our foot Soldiers to dig out the enemy fighters and kill them. This type of gut-busting infantry combat proved successful for Captain Kevin Butler of the 101st Airborne Division.

No matter how many air strikes he called in and how many smart bombs were dropped, his company continued to receive incoming mortar fire and small arms fire from caves hidden in the ridgelines above him. At times, the Al Qaeda fighters would emerge from their caves and taunt our boys, making fun of our inability to kill them with our smart bombs. Captain Butler eventually killed a number of these jokers, using a dime store 60mm mortar and timing an airburst above them as they emerged from a cave to taunt him once again.

This is evidence that taking-the-fight-to-the-enemy with rifles, pistols, grenades and mortars proved to be more effective in this terrain than the use of airstrikes.

Unfortunately, there is no hard evidence nevertheless to suggest that we accomplished our original goal. At the end of Operation ANACONDA, as well as Tora Bora, the majority of the Al-Qaeda fighters escaped, leaving behind a few bodies and many empty caves.

Of much greater significance is the fact that 10th Mountain Division units involved in Operation ANACONDA were pulled from the battle after two weeks and then redeployed to Fort Drum, N.Y. Amid great pomp and circumstance these units arrived back home to the cameras of ABC's Good Morning America. Later in the broadcast, a news anchor reported that the first elements of a 1,700-man strong British Royal Marine battle group began to arrive in Afghanistan. It was also reported that no other U.S. troops were planned to replace the Soldiers of the 10th, or in the words of the division PAO, "we have the Brits now."

I truly wonder if the significance of this one broadcast was recognized for the greater statement it made regarding the decline of our own combat capabilities. A country with one of the smallest armies in the world was formally asked to pick up the ball from the country with the largest and best financed military in the world. This indeed can qualify as an unqualified Wakeup Call.

Gary R. Stahlhut is an Army Reserve officer and combat veteran with 26 years of active and reserve duty. He can be reached at Gary.R.Stahlhut@eudoramail.com

The following is an unvarnished report from a Senior NCO who fought in ANACONDA. I made some punctuation and spelling corrections. Clarifications in brackets [ ].

Rakkasan lessons learned

By a 187th Regiment 1st Sergeant

I guess the biggest lesson I learned is nothing changes From how you train at jrtc. We all try to invent new dilemmas and hp's because it's a real deployment but we end up out-smarting ourselves. Go with what you know, stick

with how you train.

Some of the things in particular were Soldier's load, because you're in the mountains of Afghanistan you try to invent new packing lists, or new uniforms. Some units went in with gore-tex and polypro only, when the weather got bad they were the only ones to have cold weather injuries that needed to be evaced. We've all figured out how to stay warm during the winter so don't change your uniforms. It was never as cold as I've seen it here or Ft Bragg during the winter.

Because of the high altitude's and rough terrain we all should have been

combat light.

That's the first thing you learn at jrtc [Joint Readiness Training Center, Fort Polk, Louisiana], you can't fight with a ruck on your back.

We packed to stay warm at night. Which was a mistake; you take only enough to survive until the sun comes up.

We had extreme difficulty moving with all our weight. If our movement would have been to relieve a unit in contact or a time sensitive mission we would not have been able to move in a timely manner. It took us 8 hours to move 5 clicks. [Editor that's less than 1 mph]

With just the [Interceptor hard body armor] vest and [Enhanced Tactical Load Bearing Vest or the MOLLE vest] lbv we were easily carrying 80 lbs. Throw on the ruck and your sucking.

We out-smarted ourselves on how much water to carry. We took in over 12 quarts per man on our initial insertion, which greatly increased our weight. In the old days you did a three-day mission with 6 quarts of water, and that was on Ft Campbell in the summer. Granted we were all heat exhaustion [casualties] at the end but it's more than do-oable. I say go In with six quarts, if your re-supply is working than drink as much as possible keeping the six quarts in case re-supply gets weathered out. We also over tasked our helicopter support bringing in un-needed re-supply because we've lost a lot of our needed field craft.

We didn't even think to take iodine tablets [to purify water from melted snow etc.] until after we got on the ground.

If you're in a good fight your going to need all your birds for medevac and ammo re-supply.

Bottom line is we have to train at the right Soldiers load, relearn how to conserve water. [Editor: CARRY THE DAMN AMMO YOU WOULD IN COMBAT NOW IN PEACETIME!]

How many batteries does it take to sustain for three days etc.? Take what you need to survive through the night and then wear the same stuff again.

The next day, you can only wear so much snivel gear it. Doesn't do any good to carry enough to have a different ward robe [set of BDUs] every day. Have the bn invest in gore-tex socks, and smart wool socks; our battalion directed for every one to wear gore-tex boots [Intermediate Cold Weather Boots] during the mission, you can imagine how painful that was. 71 gave up my boots to a new Soldier who didn't have any so I wore jungle boots, gore-tex socks and a

pair of smart wool socks and mv feet never got wet or cold even in the snow.

You need two pairs [of boots] so you can dry them out every day.

All personnel involved hated the lbv its so constricting when you wear it with the vest, then when you put a ruck on it cuts off even more circulation.

I would also recommend wearing the body armor during all training, I doubt if we'll ever fight without it again.

It significantly affects everything that you do.

Equipment wise, our greatest shortcomings were optics and organic or direct support long-range weapons. After the initial fight all our targets were at a minimum of 1500m all the way out to as far as you could see. Our 60[mm] and 81[mm]'s accounted for most of the kills. Next was a Canadian Sniper team with a MacMillian .50 cal [sniper rifle]. They got kills all the way out to 2500m.

The problem with our mortars was there as a 24 hour [Close Air Support] cas cap. And they wouldn't fly near us if we were firing indirect. Even though our max ord[nant: how high mortar rounds arc into the sky] was far beneath their patterns. Something for you and your alo [Air Liaison Officer] to work out. The other problem was the Air Force could never fly in small groups of

Personnel, I watched and called corrections on numerous sorties and they could never hit the targets. My verdict is if you want it killed use your mortars. Pay close attention to ti-hz direction of attack your ALO is bringing in the CAS. Every time it was perpendicular to us we were hit with shrapnel. Not to mention the time they dropped a 2,000 lbs [bomb] in the middle of our company, it didn't go off by a sheer miracle I'm sure. [Marine] Cobras and 2.75" [rockets] shot at us. Also, once again, they were shooting perpendicular to our trace. Aviation provided the most near misses of all the things we did.

I recommend all sl's [Squad Leaders] and pus [Platoon Sergeants] carry binoculars with the mils reticle. Countless times tl's [Team Leaders] and sl's had the opportunity to call in mortars. More importantly is leaders knowing how to do it. Our bn has checked all the blocks as far as that goes. Guess what? they still couldn't do it. Especially the psgts contrary to popular belief its not the pl [Platoon leader] who's going to call it in its the Soldier in the position who will. If you don't have the binos guess what? You have to wait for somebody to run to the M240[B Medium Machine Gun] position to go get them. Also same goes with not knowing how to do It, you have to wait for the FO [artillery or mortar Forward Observer] to move to that position.

Plugger [AN/PSN-11 Global Positioning System] battle drill is the way to go, even with the civilian models [Signals are unscrambled now thanks to President Clinton]; the contour interval on the maps is outrageous so terrain association was difficult. Range Estimation was probably the most important or critical thing you do. If you close on your estimation you'll get the target. We all carried in 2 mortar rounds apiece and that was more than enough. We took mix of everything; the only thing we used was wp [White Phosphorous] and he [High Explosive]. All together we took in at least 120 rounds as a company

Its was always seats out due to the limited # of ac [aircraft] and the # of personnel we had to get in. That presents a few problems. Offloading a CH-47 on a hot lz [landing zone] packed to the gills is an extremely slow process (2-3 minutes). Landing was the most dangerous part. While we were there just because of the conditions and terrain, if you crash without seats and seatbelts your going to have a lot of broken bones. If possible maybe you

could send in the first few lifts with seats in, that will get the helo off the lz much quicker then following ac seats out. Food for thought

Just like the Vietnam the pilots were courageous and will do all and even more of what you ask of them. However, re-supply was a big difficulty. Problem was they never put the right package at the right place and you know what that means, especially when its 120mm mortar rounds that fell into a deep ravine. Fix was put a lno [Liaison Officer] on the bird with grids frequencies's and call signs. Our S-4 had a group of supply sergeants that would accompany the re-supply's. Also as the S-3 push the birds down to the

company freqs. That killed us the whole time. Bn would never push the birds down to us so they were always landing in the wrong place or dropping off resupply in the wrong place. Same with AH-64s [Apache Attack helicopter

gunships] we always say give them to the user but we never do it. We always had to relay thru the S-3 to give corrections.

Flying was by far the most dangerous thing we did while we were there.

The environment was extremely harsh. The cold wasn't that bad, its the hard cold dry wind that will eat you up like you wouldn't believe. Chapstick, chapstick, chapstick, sun screen, sun screen, sun screen.

[4x2 All-Terrain Vehicles made by John Deere] Gators, didn't hold up to good, that place eats up tires like you wouldn't believe. [Editor: why we need TRACKED vehicles] They're a great thing to have when their running. Also there real easy getting them into to the fight, getting out is a different story, your always scrounging for ac when its time to go. So be prepared to leave a few Gators. [WTFO?]

We used the [Javelin missile Command Launch Unit infared thermal sights] clu's a lot, every night for that matter. Beautiful piece of equipment. They consume a lot of batteries and add a lot of weight. After it snowed, two in the company stopped working until they dried out a few days later. Other than that they held up real well.

Go in with a good or should I say great [battlesight] zero on all your weapon's. We never got a chance to re zero while we were there. Also zero all your spare weapons for replacements etc. On our last mission I hit a dud M203

[grenade] at 75m with one round from my M4 using my M68 [Close Combat Optic]. It held a zero great. A 1SG [1st Sergeant] doesn't normally abuse his weapon like a young Soldier does though. However, if they treat their weapons like tiller nintendos they should be alright.

Our bn bought the ammo bags for the M240 [B Medium Machine Guns] from London Bridge, they worked great.

Knee pads are a must, needless to say not all personnel had some msr stoves are the shit, and they burn any kind of fuel. Quality sun glasses probably more important [as] would be safety or shooting glasses. Bolle goggles are the way to go if you can afford it.

We had one guy who was hypothermic one night, the medics and a wool blanket saved his ass. Green wool still can't be beat.

Fleece gloves are the best.

We also eventually (after we were done) received Barrett .50 cals [2+ km range Anti-Tank Rifles] for our snipers. Their M24's [308 caliber, 7.62mm range only 1 km] never got used because of the extreme ranges. I think each company should have one. Or a sniper team or a M2 [Heavy Machine Gun] with crew.

Lots of thermite grenades and C-4, we used them a lot our engineers were great

Proficiency with the M203's [Grenade Launchers] right now there isn't available sight for the M-4 [5.56mm Carbine], so lots of practice with Kentucky windage. Lots of HE also mounting brackets for the [an/] peq-2 [Night laser aiming device] for the at-4's [M136 84mm disposable rockets] the smaw-d [Disposable version of 83mm shoulder fired medium assault weapon rocket

launcher] comes with one. Also the smaw-d is smaller, easier to carry and hits significantly harder. Won't collapse a cave--but will definitely clear it.

Soldiers did great you can always depend on them. They are extremely brave and want to fight. Gotta do realistic training, they'll do it just like we teach them, they'll patch a bullet hole just like you taught them in EIB, but they won't take off the Soldier's vest to check for more bullet holes etc.

Because of the extreme ranges you need the 3x adapters for the [AN/PVS-7B Night Vision Goggles] nvg's

There's a lot more I could talk about but probably better left unsaid on e-mail. Hope this gives you some food for thought"

COMMENTS

Internally, the OSD leadership should ask some hard questions about ANACONDA:

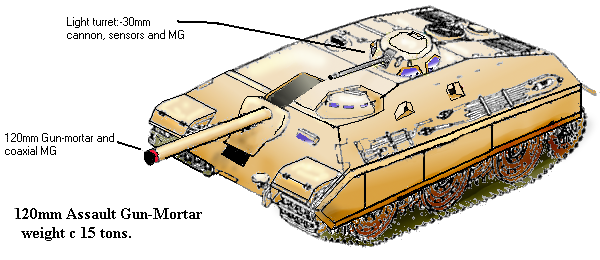

* Why was there NO ARTILLERY BROUGHT INTO AFGHANISTAN FOR THIS FIGHT?

Did Secretary of the Defense Rumsfield "do an Aspin" and deny artillery to our fighting men so he could showcase his favored aircraft delivered firepower and later use a success in Afghanistan as an excuse to get rid of Army gun artillery just like the missile-crazy Navy got rid of battleships?? Notice the U.S. marines, the biggest braggerts on earth, didn't bring any artillery during their short time ashore in Afghanistan...we certainly would have heard about their "big guns". Was this no accident? Or was it someone else that told everyone no arty in Afghanistan?? Who determined the force structure would have no artillery? CENTCOM? This is a telling question in light of Rumsfield's DoD trying to cancel the Army's Crusader self-propelled howitzer system...We have been prepping drop and landing zones with arty for well over 6 decades and suddenly for ANACONDA we decide its not necessary?

The ambush that November day nearly 37 years ago was a total surprise to the American column on its way to Landing Zone Albany in the Ia Drang Valley. The well-prepared North Vietnamese attack separated, killed and wounded many American troops. In some areas, the North Vietnamese were inside the defensive perimeter, moving toward the positions occupied by the Americans.

Often on the battlefield, a shot would ring out, followed by a scream. The enemy was taking no prisoners.

Lt. Bob Jeanette, a weapons officer of the 2nd Battalion, 7th Cavalry, was severely wounded, but had a radio. "As it got dark, I was still in the same position. I was trying to maintain contact with whoever I had talking to me back at brigade. There was a lull in the battle, and suddenly I was talking to an artillery outfit.

"The North Vietnamese were now running around the area, and we could see them moving. Bunches of 10, 20, more of them circling the perimeter of the landing zone. It was maybe 150 yards to the landing zone perimeter, and the enemy were between us and them."

Ultimately, Jeanette was able to convince the artillery unit to bring high explosive rounds down on top of the enemy.

"I never really knew how effective that artillery fire was until two things happened," he remembered.

The first incident happened while he was recovering from wounds at St. Albans Navy Hospital in New York, "I met someone who had been in that fight, a 2nd Battalion, 7th Cavalry guy, who came over to me and thanked me for that artillery fire. I was out in the halls on my crutches for exercise and he came up to me on crutches, too. He had an empty trouser leg. He told me the artillery took his leg, but it saved his life and he was grateful. I was stunned."

Later at Fort Levenworth, Jeanette met a sergeant who was in the same battle whose position was about 50 yards from his position. "Sgt. Howard said that every time the enemy got close to them, the artillery would come in close, too, and really whack them. He said the artillery fire was the only thing that kept the enemy away and kept them alive."

The above is just one of many war stories from the Vietnam conflict, but maybe the civilian movers and shakers in Washington need to re-read We Were Soldiers Once And Young" by Lt. Gen. Hal Moore and Joseph Galloway.

The scene described occurred after air strikes by the highly efficient A-1E SkyRaiders. Despite napalm and other ordnance, many enemy soldiers remained alive. It took artillery fire to save American lives.

That was long ago. But proof that it wasn't just an artifact of history emerged only weeks ago during Operation ANACONDA in Afghanistan, when a U.S. infantry company found itself under mortar and rocket fire for nearly 12 hours without close air support. Unfortunately, it also had no artillery support: the unit's artillery had been left behind in the U.S.

Pentagon civilians who threaten to cut the Crusader artillery system seem to have forgotten their history. Airpower is a wonderful tool, but it isn't enough. Infantrymen on the ground need the combined firepower of both close air support and artillery.

Strangely, combat veterans who understand the value of combined firepower have been deafeningly quiet about the need for more advanced artillery. That's hard to understand, because they know air power has its limitations and that their grandsons will pay the price.

In the late 1940s when air power advocates tried to eliminate aircraft carriers and shift responsibility for power projection to the Air Force, active duty admirals revolted, cranked up the public relations machine on the need for Naval airpower and won. [EDITOR: now we have a dozen bloated aircraft carriers that eat bloated airplanes that cannot render CAS and too far away to help inland fights]

The battle for Crusader may be over. The "after action report" will be prepared soon. Maybe the report should look at why the Army failed to convince the Pentagon, public and President that the Crusader was a vital asset. If so, it should also examine why the combat veterans who experienced the live-saving value of artillery hid in their foxholes.

In an attempt to make excuses for Army light infantry leaders wanting to hog up all the action to themselves and not bring any field artillery or use any mortars for LZ prep fires, the U.S. Army Center for Lessons Learned (CALL) Afghanistan report states:

http://call.army.mil/products/handbook/02-8/02-8ch2.htm

"The land component does not have field artillery that would normally deploy with a unit. The only indirect fire assets within the battalion are mortars. These mortars provide fires directly in support of the battalion out to

limits of the weapon's range. Beyond that range, commanders must request air support to attack targets in their operational area".

This is TOTAL BULLSHIT. Its a bald-faced lie. We deliberately co-locate field artillery units on the same Army posts where light infantry are at for the very purpose that they can train and deploy together. This is politically correct BS to prop up infantry ego and not wage combined arms warfare with the rest of the Army which is required to WIN on the modern, non-linear battlefield (NLB) against cunning enemies who know thew terrain better than we do and outnumber us.

* Why was each battalion maneuvered on the ground remotely by a different brigade commander? Why were the two brigade commanders (each maneuvering one battalion) from different divisions reporting to a 1 star and a two star (BG from 101st and MG from 10th Mountain)?

Perhaps answers to these questions would do much to illuminate the condition of our warfighting readiness, as well as the confused nature of Army senior leadership. Of course, these questions only begin to scratch the surface concerning the host of other things, but I think this UK

reporter has shed some light on the reality of the U.S. Army.

Remember what then LTG Ridgway said after assuming command of the 8th Army in Korea:

"The primary purpose of an Army - to be ready to fight effectively at all times - seemed to have been forgotten.... The leadership I found in many instances was sadly lacking and I said so out loud. The unwillingness of the army to forgo certain creature comforts, its timidity about getting off the scanty roads, its reluctance to move without radio and telephone contact, and its lack of imagination in dealing with a foe whom they soon outmatched in firepower and dominated in the air and on the surrounding seas - these were not the fault of the Soldier, but of the policymakers at the top."

Our problems are not just equipment or technology related. They are profoundly human which is why reorganization and reform offer the only path to transformation.

Ambush at Takur Ghar: Fighting for Survival in the Afghan Snow

By Cincinnatus for SOF magazine

www.youtube.com/watch?v=sm1XY6_cOb8

www.youtube.com/watch?v=sm1XY6_cOb8

www.youtube.com/watch?v=zw7dn49ZnEA

www.youtube.com/watch?v=zw7dn49ZnEA

The B-1B has a great record of staying aloft to provide stand-off, distant air support (SODAS) but is extremely expensive to operate and not likely to be available to all Army maneuver units

www.youtube.com/watch?v=EK3rI7zq9OM

www.youtube.com/watch?v=EK3rI7zq9OM

www.youtube.com/watch?v=2u2TxVA23W4

www.youtube.com/watch?v=2u2TxVA23W4

www.youtube.com/watch?v=H6r3U4NW3ck

www.youtube.com/watch?v=H6r3U4NW3ck

"I would like to pass on a few things learned during our recent deployment. It won't be in a specific order so bare with me.

David Hale, Editor of the Lawton Constitution newspaper wrote in his editorial:

Battle: Secretary Rumsfeld, airpower advocates about to overrun "Firebase Crusader"

* Why were MPs suddenly converted to infantrymen to fill out under-strength units in the two battalions from two different divisions (10th and 101st) that were deployed to ANACONDA? This goes to the heart of the readiness/training problem in the Army.

Bravery And Breakdowns In A Ridgetop Battle: 7 Americans Died in Rescue Effort That Revealed Mistakes and DeterminationBy Bradley Graham, Washington Post Staff Writer

Robert's Ridge aka Takur Ghar after the snow meltedPART 1

www.youtube.com/watch?v=kWA5vEkDJlE

A call had come in to headquarters just before daybreak: A Navy SEAL team was taking fire on an Afghan mountain ridge and needed help. As they raced in helicopters toward the site, Capt. Nathan Self and his platoon of Army Rangers were excited about the prospect of engaging al Qaeda. They'd spent more than two months in Afghanistan without a firefight.

They didn't know how many enemy fighters to expect. They didn't know exactly where the enemy might be. They didn't know exactly where the SEALs were, either. They did know that they were losing the advantage of darkness, flying by dawn's early light.

Two U.S. helicopters already had taken fire while trying to land on the ridge during the previous three hours, and two U.S. soldiers had been killed. Around 6:15 that morning, March 4, Self's chopper, a black, 52-foot Chinook, reached the ridge and started to descend.

Absurdly DARK GREEN MH-47 Chinook helicopter should be LIGHT GRAY to blend into the sky--and not be such an easy target for enemy fireThe chopper was still about 20 feet off the ground when a rocket-propelled grenade slammed into its right engine, knocking it out. Enemy machine-gun fire ripped through the fuselage. Bullets started punching holes in the cockpit glass.

The chopper shook and dropped, landing hard enough to send the Rangers and aircrew sprawling across the floor. Within seconds, four men on the helicopter were killed, and the survivors were fighting for their lives.

By day's end, a seventh Soldier, an Air Force search-and-rescue specialist, would bleed to death as Self's appeals for urgent evacuation were rejected by his superiors, who wanted no more daylight rescue attempts.

What became a 17-hour ordeal atop a frigid, desolate and enemy-ridden mountain ridge cost seven American lives, more combat deaths than any U.S. unit had suffered in a single day since 1993, when 19 Rangers and Special Operations soldiers died in battle in Mogadishu, Somalia. How the operation was conducted revealed serious shortcomings in U.S. military coordination and communication in Afghanistan. How it unfolded highlighted the extraordinary commitment of American soldiers not to leave fallen comrades behind: The entire episode spiraled out of an attempt to rescue a single SEAL, who had fallen out of the initial helicopter and was quickly shot by the enemy.

The firefight at Takur Ghar mountain came on the third day of Operation ANACONDA, a three-week-long U.S. sweep against al Qaeda and Taliban forces in the Shahikot valley in eastern Afghanistan. The Mogadishu battle nine years ago precipitated the withdrawal of U.S. forces from Somalia. This one, Pentagon officials credit with reinforcing the Bush administration's commitment to pursue the war even in the face of U.S. military casualties. Efforts are underway to award some of the military's highest decorations for valor to those who fought on the mountain.

Even so, the circumstances that led to the firefight on the ridge have been subjected to extensive review in the Special Operations Command, which has responsibility for some of the elite U.S. military forces, including the Navy SEALs. Special Operations commanders ran the star-crossed rescue effort.

Close examination of the effort indicates that U.S. intelligence sources failed to detect enemy fighters on the ridge, leaving commanders to assume it was safe. Even after learning otherwise, U.S. military officials dispatched the SEALs back to the ridge where they had first come under fire, rushing them headlong into another ambush. Self and his Rangers then ended up going to the same spot unaware, because of communications equipment glitches, that the SEALs had retreated from the ridgetop.

An AC-130 gunship that could have provided covering fire for the Rangers was pulled from the scene just as they arrived because rules prohibited use of the low-flying, slow-moving warplane during daylight. An unmanned Predator drone [ED: un-armed and couldn't do squat] took live video of the unfolding battle, giving commanders at the operation's command post at Bagram air base about 100 miles to the north and as far away as U.S. Central Command in Tampa real-time images of the firefight. But little of the information it initially gleaned was passed to the troops.

The episode has prompted some changes within Special Operations intended to improve communications and the flow of information to rescue teams. Commanders also have taken steps to promote closer coordination between conventional and Special Operations units in Afghanistan, which have separate chains of command.

This account is drawn from extensive interviews with the Rangers, who are back in the United States, as well as Air Force air controllers, Air Force para-rescuemen, and the Army helicopter crews who flew the Special Operations team and Rangers to the ridge. The chopper crews asked that only their first names be used; one Ranger requested his name be withheld.

Those who survived the battle are reluctant to criticize the decisions of superiors. But some senior military officers familiar with the rescue operation have raised questions about how it was managed. Could aircraft have attacked the al Qaeda positions before the rescuers set down? Could the communications glitches that hampered the rescue effort have been avoided? Could the Rangers have been dispatched sooner, allowing them to maintain the advantage of darkness?

"Instead, it was the shootout at the OK Corral in the broad morning light," one Ranger officer said.

"A Dominating Piece of Terrain"

PART 2

www.youtube.com/watch?v=HR24K3pIh88

The first signs of trouble came about 3 a.m., when an MH-47E Chinook carrying Navy SEALs and an Air Force Special Operations combat controller tried to land on a ridge on the eastern side of the Shahikot valley, on a mountain the U.S. military dubbed "Ginger."

U.S. military commanders launched Operation ANACONDA on March 2 against members of al Qaeda and their allies in the Taliban militia. It was still winter in Afghanistan's forbidding eastern mountains, where night-time temperatures dipped into the twenties and the snow on ridgelines was knee-deep.

Military planners had intelligence that enemy forces were concentrating in the Shahikot valley. The plan was for friendly Afghan troops to lead an assault from the northwest, pushing the enemy fighters into U.S. blocking positions along the eastern ridge.

Instead, the Afghan advance stalled and the eastern ridge itself was found to be teeming with al Qaeda fighters. As U.S. 10th Mountain Division troops tried to get into position to seal off valley exit routes in the south, they came under heavy mortar and machine-gun fire from around Ginger.

Elements of the 10th Mountain regrouped with plans to insert additional forces north of Ginger and move south to attack. At the same time, on the night of March 3, U.S. commanders sought to gather a firsthand picture by placing a reconnaissance team on the ridgetop.

"It was a dominating piece of terrain, and if we had observation up there, it gave us a 360-degree look across several trails as well as Shahikot," explained Army Maj. Gen. Franklin L. "Buster" Hagenbeck, who was commanding Operation ANACONDA from his headquarters at Bagram.

The ridgetop, at 10,200 feet, was thought to be uninhabited. U.S. warplanes had repeatedly bombed the area, and overhead surveillance had produced little sign of life on top. Commanders chose a reconnaissance team of seven Special Operations troops, all but one of them Navy SEALs, to go to Ginger.

Helicopter maintenance problems and a B-52 bomber strike that night forced a delay in the reconnaissance mission. This raised concerns that the SEALs, who were to be dropped off at the base of the mountain and climb to the ridgetop, might not make it up before daylight. A decision was made to fly them directly to the top.

The Chinook carrying the reconnaissance team, code-named Razor 3, left a staging area in Gardez with a second helicopter, Razor 4, which was to drop another Special Operations team elsewhere in the valley and then rendezvous with Razor 3 for the return trip. The choppers were flown by the 160th Special Operations Aviation Regiment, a special Army unit known as the Night Stalkers. Its pilots are accustomed to operating on covert missions behind enemy lines. The 2nd Battalion of the 160th had been in Afghanistan since October, flying some of the war's most sensitive missions.

"Before we went in there, the plan was for an AC-130 to recon the area and make sure it was all clear," recalled Alan, the pilot of Razor 3. "With a recon mission like this, you don't want to land where the enemy is."

The helicopter touched down in a small saddle near the top of the ridge, and the SEALs moved into position at the rear door to get off. At the head of the line was Navy Petty Officer 1st Class Neil C. Roberts.

The chopper's crew reported the presence of a heavy machine gun about 50 yards off the nose of the aircraft. But the gun appeared unmanned, a not uncommon sight in Afghanistan, whose mountain ridges and caves are littered with seemingly abandoned tanks and antiaircraft guns. The SEALs announced they were leaving.

At that moment, machine-gun fire erupted from several directions, ripping into the chopper. A rocket-propelled grenade came flaming in from the left, tearing through the cargo bay and exploding.

"I saw a big flash," said Jeremy, a crew chief. "By the time I got my senses back, we were flying down the mountain."

Dan, the crew chief on the rear right, shouted to the pilot: "We're taking fire! Go! Go! Go!" The pilot applied full throttle, but the grenade had short-circuited the aircraft's electrical power and damaged its hydraulic system. The machine-gun fire had punctured oil lines and wires. The chopper wobbled and jerked as it lifted off.

As it lurched, Roberts went flying off the back ramp.

Alexander, one of the chopper's rear crew chiefs, tried to grab him. But Alexander lost his own balance on the ramp, slipping on draining oil and hydraulic fluid. He dangled off the edge, saved only by his safety harness. Dan yanked him back inside.

The pilot, thinking an engine was out, sent the chopper into a dive, hoping to gain airspeed. Quickly realizing both engines were working, he leveled the chopper and tried to climb.

"The thing was shaking like a washing machine out of balance," he recalled. "There were holes in the rotor blades, and the hydraulics were doing some funny things."

Told that Roberts had fallen out, the pilot tried to turn back. But with no hydraulic fluid, the controls locked up. Dan, having just hauled Alexander to safety, grabbed the handle of a hand pump and started furiously pumping spare quarts of hydraulic fuel into the system.

"The controls came back," the pilot said. "I leveled it out and said, 'Sorry guys, we're going to have to abort.'"

The Chinook limped north, its controls briefly freezing twice more as the crew desperately looked for a place to land in the valley below. With its radio out, Razor 3 could not contact Razor 4, which was beginning to wonder why its buddy was a no-show at the rendezvous point. Razor 3 finally came to rest at the north end of the valley, about four miles from the ridgetop. crew members were not even sure they were out of the battle zone.

The SEALs and aircrew got off the chopper to take up fighting positions. Mike, the flight engineer, grabbed a picture of his 2-year-old as he got off, wondering whether he would ever see his child again.

Razor 3 soon received word that Razor 4 was on the way to pick them up. It arrived within 30 to 45 minutes. The two teams discussed returning immediately to Ginger to rescue Roberts, but with the crew of Razor 3 also on board, Razor 4 would be too heavy to reach the ridge. Leaving the Razor 3 crew on the valley floor while Razor 4 ferried the SEALs back also would not work: Reports were coming across the radio of enemy forces about 1,200 yards away and closing in fast.

So the only option was to go to Gardez, drop off Razor 3's crew, then take the SEAL team in Razor 4 to hunt for Roberts.

Two of Razor 4's crewmen had gone over to Razor 3, which was about 60 yards away, to do a final sweep of the aircraft. Suddenly in a rush to leave after getting word of the enemy fighters nearby, those on Razor 4 tried, using laser signals and other means, to get the attention of the crewmen on the other helicopter -- in vain.

"It was just a moment of pure panic," the pilot of Razor 4 recalled.

Lifting off in a hover, Razor 4 landed in front of Razor 3, loaded the other crewmen and hustled to Gardez. There, it dropped off the other crew and -- with the SEALs and Air Force Tech. Sgt. John A. Chapman, the air controller, on board -- set out back to Ginger, and Roberts.

"This Is Going to Hurt"

At Bagram air base outside Kabul, the command staff was trying desperately to gather some sense of Roberts' condition and location. U.S. military officials say no one knows exactly what transpired during the next few minutes on the ridge. There were no surveillance aircraft over the mountain at the time Roberts fell from the helicopter.

Based on forensic evidence subsequently gathered from the scene, officials with the U.S. Special Operations Command concluded that Roberts survived the short fall, likely activated an infrared strobe light and engaged the enemy with his M249 Squad Automatic Weapon, a light machine gun known as a SAW.

"He was there moving around the objective for a period of time, at least half an hour," Hagenbeck said. An AC-130 gunship moved over the area and reported seeing what the crew believed to be Roberts surrounded by four to six enemy fighters. As a Predator drone arrived to provide a video picture, the strobe light went out.

Hagenbeck says the imagery taken by the drone appeared to show him being taken prisoner. "The image was fuzzy, but we believe it showed three al Qaeda had captured Roberts and were taking him away around to the south side of Ginger and disappearing into a tree line," Hagenbeck said. "That was 15 to 20 minutes before the first rescue team arrived."

The review by Special Operations Command concluded that Roberts was shot at close range. His SAW was found near his body with blood on it, along with other evidence that he had been able to fire some shots. Some ammunition remained in the gun, suggesting it had jammed.

It is unclear just how much information commanders were relaying to Razor 4 as it sped Roberts' comrades back to Ginger. Uncertain about Roberts' situation, the rescue team approached the ridgetop cautiously, resolved not to fire wildly lest they hit the stranded SEAL.

The pilot of Razor 4 had never flown into a hot landing zone. The briefing he had received from Razor 3's pilot gave him some confidence that he wouldn't be caught by surprise. He figured all he had to do was put the chopper on the ground long enough to let the SEALs dash out.

About 40 feet above the ground, the pilot saw the flash of a machine-gun muzzle off the nose of the aircraft. "I thought, 'Oh, this is going to hurt,'" he said. "And then the second thought was, 'How do I get myself into this?' But we had to go. We had to put these guys in."

Rounds of gunfire started hitting the aircraft, "pinging and popping through," in the words of one crew chief.

Hagenbeck, watching the Predator's pictures, saw Razor 4 land and the SEALs and Chapman rush off toward the enemy positions. He had little view of the enemy fighters, who were hidden under trees, dug into trenches and obscured by shadows.

"They didn't take cover, they just started moving immediately to where they thought that Roberts was located, right off the nose of the helicopter," Hagenbeck said of the U.S. commandos. "They moved straight out and took withering fire and they returned it as well."

The most prominent features on the hilltop were a large rock and tree. According to the Special Operations Command review, Chapman saw two enemy fighters in a fortified position under the tree. He and a nearby SEAL opened fire, killing both fighters.

The Americans immediately began taking fire from another bunker position about 20 yards away. A burst of gunfire hit Chapman, mortally wounding him, the review said. The SEALs returned fire and threw grenades into the enemy bunker directly in front of them.

As the firefight continued, two of the SEALs were wounded by enemy gunfire and grenades. The SEALs decided to disengage. They shot two more al Qaeda fighters as they moved off the mountain peak to the northeast, according to the official review.

As they moved down the side of the mountain, a SEAL contacted the AC-130, code-named Grim 32, and requested fire support. The gunship responded with covering fire.

As the SEAL team battled, Capt. Self and the 19 other Rangers in the "quick reaction force" took off from Bagram in two Chinooks -- code-named Razor 1 and Razor 2 -- and headed for Ginger, about an hour away. It was shortly after 5 a.m.

"You Have This Dilemma"

PART 3

www.youtube.com/watch?v=GhG4dfVhGq4

The Rangers left Bagram with only sketchy information about where they were headed and what they were to do. Initially, they had been told only that a helicopter had been hit by enemy fire and forced to land; later, they learned that someone had fallen out. A lightly armed infantry unit, the Rangers specialize in behind-the-lines evacuation and reinforcement missions. They work frequently with SEALs and other Special Operations teams.

More specific guidance arrived as the Rangers flew toward the scene. They received orders to link up with the embattled SEALs and extract them, along with the commando who had fallen. Beyond that, many details were lacking.

"You have this dilemma: Hold guys on the ground longer so they know exactly what they're going to do, or push them ahead so we can affect the situation sooner," said Self, 25, a Texas native and West Point graduate who had commanded the platoon for 17 months. "A quick reaction force is never going to know everything that's going on. If they did, then they wouldn't be quick."

At headquarters, commanders tried to notify the Rangers that the SEALs had retreated from the ridgetop and to direct the helicopters to another landing zone further down the mountain. Due to intermittently functioning aircraft communications equipment, the Rangers and aircrew never received the instructions, according to the official review. Communication problems also plagued headquarters attempts to determine the true condition of the SEAL team and its exact location.

"As a consequence, the Rangers went forward under the false belief that the SEALs were still located on top of Takur Ghar and proceeded to the same location where both Razors 3 and 4 had taken enemy fire," the review said.

Nearing the mountain, Razor 2 went into a holding pattern. Self flew ahead on Razor 1 with his "chalk," nine young men in body armor over desert camouflage fatigues. In Afghanistan since December, the platoon -- Part of Alpha Company, 1st Battalion, 75th Infantry Regiment -- had been scrambled a number of times, but it had not seen combat in the country, or anywhere else.

"The force flew to the place they knew the folks were in trouble," said a senior officer who monitored the battle. "They didn't know where the enemy or the Americans were. They were committed relatively blindly."

As they approached the landing site, the Rangers quickly found out how blind they really were. A rocket-propelled grenade knocked out the right engine, and enemy gunmen opened up on the damaged chopper.

Sgt. Philip J. Svitak, one of the forward gunners, fired a single burst of his 7.62mm gun from the copter's right side before being struck and killed. The other forward gunner, a flight engineer named David, was hit in the right leg.

"It basically just pissed me off," David said. "And I just pushed the trigger on my [Dillon Aero M134] minigun and started sweeping fire on the left. I didn't know where the fire was coming from, I just knew we were taking fire. I wasn't going to let that happen without shooting back."

The chopper slammed to the ground. David collapsed in a corner and used a lanyard from his 9mm pistol to tie a tourniquet on his leg. He knew it was broken -- every time he tried to move it, the whole thing would twist.

Bullets were zooming through the cockpit glass. A round shattered one of the pilot's legs below the knee, another knocked off his helmet. The pilot, Chuck, popped open his emergency side door and flopped onto the snow. A bullet or fragment ripped a chunk out of the left wrist of the other pilot, Greg. Another bullet cut into his thigh. He staggered out of the cockpit toward the rear of the aircraft, holding his wrist as it spurted blood.

The incoming machine-gun fire was turning the aircraft's insulation into confetti. An RPG shot through the right forward window, hit a high-altitude oxygen console on the wall and started a fire.

"It's chaos at that point. Nobody has a grip on what's going on," said Cory, the chopper's medic. "I took three rounds in the helmet. It knocked me down," he recalled. "I was on my back. Somehow the impact caused a small laceration in my eyebrow. But it was bleeding a decent amount. I was on my back, and the blood was running down my face, and it took me a second to gain my senses and I realized I was okay."

Sean, the crew chief on the right rear side, shouted to Cory, "You need to put that fire out." But the forward fire extinguisher was missing. Brian, the other rear crewman, passed an extinguisher forward. Cory put out the fire, but the rest of the chopper was pure hell. The air was laced with smoke and bullets, and the enemy seemed to be everywhere.

"I Saw the Tracers" The Rangers were supposed to exit down a back ramp in an order they had practiced countless times. Those on the left would assemble outside on the left side of the chopper. Those on the right would assemble right.

But the moment had turned into a mad scramble to get out in whatever order they could. One Ranger, Spc. Marc A. Anderson, was shot and killed while still in the helicopter. Two others -- Pfc. Matthew A. Commons and Sgt. Bradley S. Crose -- were gunned down on the ramp.

At 21, Commons was the youngest in the group, with a reputation as a good-humored, enthusiastic Soldier. Crose, 22, a leader of one of the platoon's four-man teams, was a quiet professional. Anderson, 30, was a former high school math teacher who had awed his fellow Rangers with his knowledge of weaponry. Now they were dead.

The surviving Soldiers peeled off in different directions, wheeling around in the knee-deep snow, scurrying for cover behind whatever rocks they could find and firing on enemy positions.

The enemy was concentrated in two spots 50 to 75 yards away, looking down on the chopper from dug-in, fortified positions atop the ridgeline. Two or three fighters were shooting from the left rear side of the Chinook -- at about the 8 o'clock position. Staff Sgt. Raymond M. DePouli, the first Ranger out, began blasting away at them with his M4 assault rifle.

"I saw the guy shooting at me, I saw the tracers. I got hit in my body armor," said DePouli, a squad leader. "I turned and dumped a whole magazine into him. Then I just got down prone...to make sure nothing else came over the hill."

Another cluster of enemy fighters was behind a boulder and under a tree to the front of the helicopter, off to the right at about 2 o'clock. They were firing machine guns and RPGs at the Americans. One slammed near the right side of the 'copter.

Spc. Aaron Totten-Lancaster, a long-distance runner considered the fastest in the battalion, took shrapnel in his right calf. [EDITOR: how fast did he run after that?] Shrapnel also cut a wound in Self's right thigh and put a small hole in the left shoulder of Air Force Staff Sgt. Kevin Vance, a tactical air controller attached to the Ranger unit.

Another RPG soared over the Rangers' heads, skipping off the helicopter's tail. Self could see the torso of the man who fired it suddenly exposed above a boulder. DePouli, moving around from the other side of the helicopter, saw him, too, and shot him in the head.

Nearly all the Rangers were hit. A machine gun belonging to Spc. Anthony Miceli got shot up. A bullet slammed into helmet of Staff Sgt. Joshua Walker, another team leader.

Only Pfc. David Gilliam, the newest member of the platoon, avoided a hit to either his body or his equipment. He had jumped to the right side of the chopper, then scrambled to reassemble scattered ammunition belts for his M240B heavy [EDITOR: medium] medium machine gun.

Self thought that the bullets flying past sounded different from what he had expected, almost like a clicking instead of a crack. The smell, too, was something he hadn't imagined, a mixture of cedar from the trees dotting the ridgeline, fuel, gunpowder, metal, sweat, blood and something faintly like strawberries. It all seemed so strange. "You see something happening and it doesn't seem real," Self said. "We understood we were getting shot. But it just seemed like a bad movie."

Disorienting and frightening as the first intense minutes of combat were, a sense of anger and indignation quickly took hold.