"Combat Light" Soldier's Load Solution for the 21st century

1st Tactical Studies Group (Airborne) Director Mike Sparks: after 28+ years of military field experience and having solved the Soldier's load problem for myself back in 1995, I think enough-is-enough! I made this web page after reading the gear debacle in Afghanistan and the Rakkasan 1SG's call for going into combat "Combat Light".

Go to internetarchive.org to see the original presentation: www.reocities.com/usarmyafghangearproblems

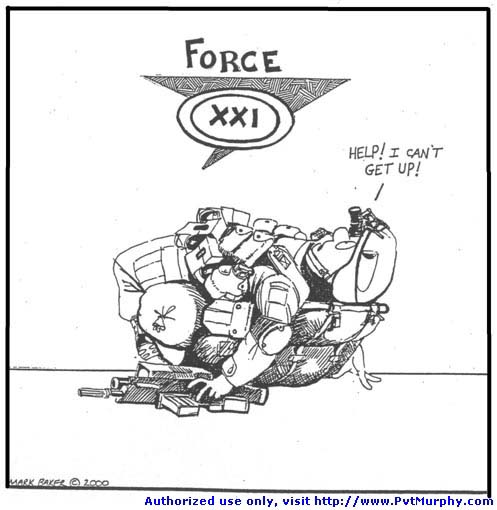

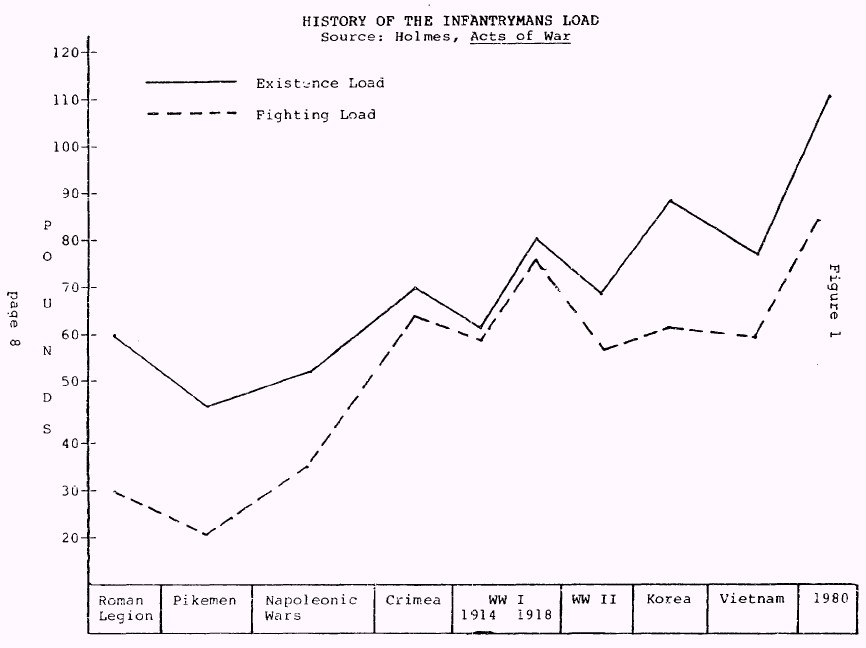

Yet, the Soldier's Load Problem is Getting Worse!

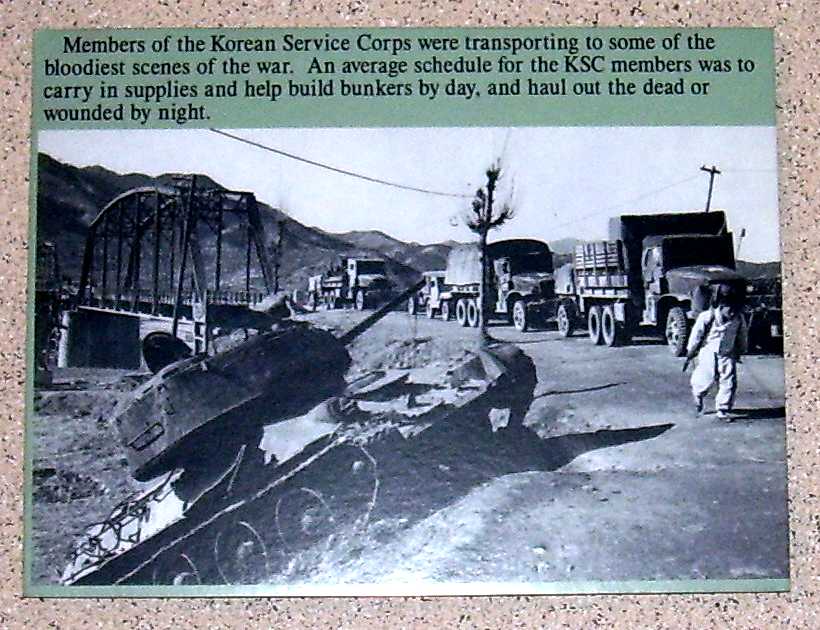

Chart from then Army Major Stephen Tate's brilliant CGSC thesis, "Human Powered Vehicles in Support of Light Infantry Operations"

Accession Number : ADA211795

Title : Human Powered Vehicles in Support of Light Infantry Operations

Descriptive Note : Master's thesis Aug 1988-Jun 1989

Corporate Author : ARMY COMMAND AND GENERAL STAFF COLL FORT LEAVENWORTH KS

Personal Author(s) : Tate, Stephen T.

Handle / proxy Url : http://handle.dtic.mil/100.2/ADA211795 Check NTIS Availability...

Report Date : 02 JUN 1989

Pagination or Media Count : 188

Abstract : This study examines the suitability of using bicycles to enhance the mobility of U.S. light infantry units. Initially the study defines mobility problems encountered by U.S. light infantry units as a result of force design. The study presents historical examples of previous military cycling operations at the turn of the century, during both World Wars, and the Vietnam Conflict. The tactical use, mobility, speed, distance, and load carrying capacity of bicycle troops during each of these periods are discussed. The present use of three bicycle regiments in the Swiss Army is examined. The impact of recent technological improvements in the bicycle industry is examined for possible military application. Keywords: Bicycle; Light infantry; All-terrain bicycle, Mobility; Soldier's load; Vietnam, Swiss army; Strategy; Tactics; Derailleur; World War II; Logistics; Military operations.

Descriptors : *MOBILITY, *LOGISTICS, MILITARY OPERATIONS, MILITARY PERSONNEL, WARFARE, GLOBAL, INDUSTRIES, ARMY PERSONNEL, CAPACITY(QUANTITY), INFANTRY, TERRAIN, CYCLES, MILITARY APPLICATIONS, LIGHTING EQUIPMENT, ARMY, VIETNAM, SWITZERLAND.

Subject Categories : MILITARY OPERATIONS, STRATEGY AND TACTICS

Distribution Statement : APPROVED FOR PUBLIC RELEASE

Vietnam: Soldiers Overloaded

www.youtube.com/watch?v=pbtujMKcVOA

www.youtube.com/watch?v=pbtujMKcVOA

Today: Soldiers STILL Overloaded

www.youtube.com/watch?v=1wCWiWDELrA

www.youtube.com/watch?v=1wCWiWDELrA

After 11 years and 1,000+ web pages [www.combatreform.org/aesindex.htm] I guess we haven't been clear enough; so this time we'll try again to define what "Combat Light" is without pulling any punches and a little help from our dear departed friend, retired Colonel David Hackworth.

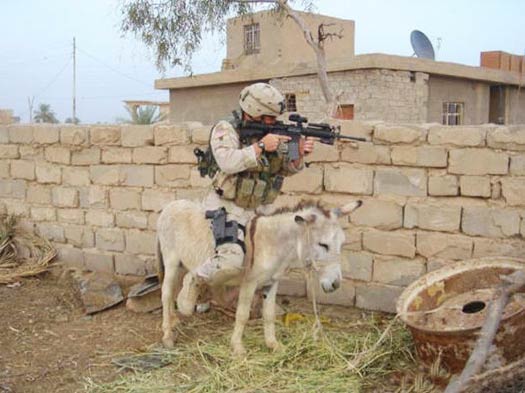

First, the planet earth has not changed that much that its not possible to have a solution that works from freezing to 100+ degrees, a "combat light" field living and fighting capability implying its light enough that you can move fast on your feet at 4-7 mph; with human or electric powered all/extreme terrain bikes that speed can increase to 25 mph. With global warming, when do we ever have winter? YES, you need hard shelters to survive on this planet spinning through space at 66, 000 mph and we propose we face this reality with our self-sustaining ISO container BattleBox system which should form our forward operating bases overseas and eliminate garrison buildings and lawn care mentalities here in the U.S. forever. Against cunning, 21st asymmetric-overmatch-seeking enemies who have "home field advantage" of being able to cache and hide their supplies amongst closed terrain and often sympathetic populace, U.S. forces projecting from CONUS have to carry everything they need to prevail in a fight. To beat the guerrilla at his own game of mobile, light infantry warfare David Hackworth-style we have to be significantly smarter and tougher than we are now through a holistic and honest bottom-up approach that leaves no stone unturned to rid every ounce possible from our Soldier's backs and places superior firepower and supplies on alternate transport platforms.

The following is our immediate solution and its worked for me for well over 10 years now in the field and it can work for YOU so that you can live in the field COMFORTABLY. The only exception is sub-zero temperature conditions where you must carry a full size sleeping bag and extra layers of insulating clothing. However, if you have to just stay ALIVE until morning in sub-zero temperatures, the set-up below will do this though you may not be COMFORTABLE.

I realize admitting that you want comfort is not allowed and a curse word ("snivel gear") in the who-has-a-bigger-penis ego-driven U.S. military; but let's stop playing games, get the "cat out of the bag" (face unpopular truths), admit that we are human beings with finite load carrying limits (no more than 1/3 of our own weight) and realize that these bloated rucksacks we see carrying comfort gear in PEACETIME are skewing our training focus and future TA-50 gear design resulting in us not performing well in actual combat as Afghanistan proved---when our entire focus should be centered on carrying COMBAT ammunition loads with the bare-minimum field living gear to survive so we can move as fast and as strong as possible. Some have termed this concept "eXtreme Soldiering" to use the vernacular of today.

IMMEDIATE SOLDIER'S LOAD FIX

1. Think Combat Light

ALL Soldiers should go to level "C" SERE training by stopping the BS initiation/harassment games at the end of basic training and incorporating survival training of 3 weeks so Soldiers can have skills to live off land's resources and not have to carry items to artificially create needed capabilities.

ALL Soldiers with laminated SERE cards in their BDU pocket.

Leadership "Combat Light" eXtreme Soldiering ethos:

D-R-O-P

Decide mobility level to accomplish mission

Reduce un-necessary gear

Organize transport means to carry unit gear

Police the ranks

Unit leaders should in mission planning have a list of the weights IN THEIR MIND'S EYE of all TA-50, weapons and ammo and add up the loads for their various Soldier assignments and make DRASTIC ADJUSTMENTS ACCORDINGLY. See: www.combatreform.org/combatjump.htm for actual Microsoft Excel spreadsheets for computing your Soldier's Load and March Speeds.

However, the following general SOP will get you "in the ballpark" for 99% of all situations except for extreme sub-zero arctic conditions.

Natick Labs even made a computer planning software tool similar to DROP called "LES" that strangely never got fielded (go to our combat jump web page for Natick's and 1st TSG (A)'s Microsoft Excel spread sheets):

www.dtic.mil/matris/ddsm/closed/ddsm0027.html

RECORD NO.: DDSM0027

OVERALL CATEGORY: Tool

STATUS: Terminated

UPDATE: August 1998TITLE: Load Expert System (LES)

SPONSOR: Army Natick RD&E Center

POINT OF CONTACT: Dr. James B. Sampson / 508-233-4698, DSN: 256-4698GENERAL OVERVIEW:

A computer-based expert system that guides unit commanders in determining a Soldier's appropriate combat load for a wide range of load, weather, terrain, and mission conditions.

LES was developed, in the long term, for use by unit commanders to assist them in the decision-making process of determining a Soldier's combat load. LES is to be used, in the short term, as a training device for junior commanders. LES will allow the junior commanders to "try out" various load configurations in different climates, terrain, and mission conditions. These commanders will then be able to receive immediate feedback on their decisions without leaving the classroom or requiring user troops.

While holding all other mission parameters constant, LES will calculate the maximum load a Soldier should carry, or the maximum velocity he can travel. LES also determines the Soldier's expected water requirement for the given mission. The commander then enters into a dialogue enabling him to adjust the combat load or modify other conditions which would lead to successful mission completion. LES then engages the commander in a dialogue designed to modify the Soldier's load or other conditions over which he has control (e.g., marching speed), in order to achieve a successful mission.

EQUIPMENT/SOFTWARE REQUIRED:

The equipment required for use is an IBM-PC or compatible with hard disk and 640K RAM.

INPUT/OUTPUT/PROCESSING:

The inputs required include basic information concerning the soldier (height, weight), the expected weather, the terrain, and mission conditions.

LES uses the heat-stress model developed at the Army's Research Institute for Environmental Medicine (ARIEM) to estimate the Soldier's core temperature and determine the likelihood that he will be able to complete the mission before becoming a heat stress casualty.

The output is a screen display that estimates the likelihood of mission success under given conditions.

DOCUMENTATION:

None.

STAGE OF DEVELOPMENT:

The initial prototype is available for others to explore for concept development.

VALIDATION:

The model continues to evolve, not in general structure, which we believe is correct, but in details and refinements. The model is supported by a variety of evidence that represents construct, convergent, and concurrent validity. The model has proven to be a rich source of insight in the analysis of complex designs for avionics architecture.

COMMENTS:

The Canadian Army is modifying LES for their equipment and mission. Variations of LES have been developed by Dynamics Research Corp, Willmington MA, using Windows and requiring more memory and a faster processor. LES has been modified for use in Natick's Integrated Unit Simulation System (IUSS).

HOW TO ACQUIRE:

To obtain, write: U.S. Army Natick Research, Development, and Engineering Center, ATTN: SATNC-YBH (Dr. Sampson), Natick, MA 01760-5020.

2. Your rucksack is a unit logpack not an individual's "mobile home"

www.defence.gov.au/budget/05-06/dar/volume_01/chapter_01/01b_year_in_view.html

An Air Force Loadmaster and three Australian Army Riggers deploy a helibox and a maxibox load from a C-130J Hercules as part of Exercise Pacific Airlift Rally in Thailand.

www.youtube.com/watch?v=duFV6AS2u7Q

www.youtube.com/watch?v=duFV6AS2u7Q

www.stage6.com/user/chasedropmaster/video/2122327/CopterBox-Discovery?ref=share_email

All rucksacks should carry is ammo, water and food in that order. Empty rucks should be able to be collected at any time and moved by unit transportation (cargo parachute or CopterBox airdrop) or sent back to be refilled and sent forward with ammo, water and food. If you have to move rucks using your own power, attach "wheels" to them and tow or push them as all-terrain carts or on all-terrain bikes. See:

www.combatreform.org/atac.htm and www.combatreform.org/atb.htm and www.combatreform.org/rucksack.htm

You do not fire & maneuver with your ruck on your back ("Combat Heavy") nor do you need your ruck to survive indefinitely in the field. Its just a means to move forward for the human back, a large amount of bulk supplies.

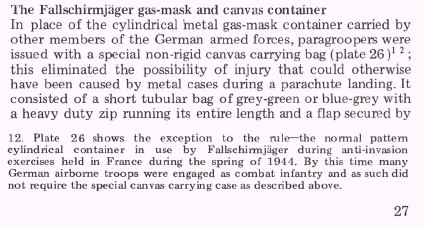

Whenever you get the even empty rucksack off your back---you shed at the very minimum 6 pounds of weight upwards to 100 pounds. This elimination of the 6-10 pound rucksack "pays" for the following "buttpack environmental field living module". It's very similar to what the German Paratroopers did in WW2. The Germans in WW2 (!) realized not to ruin foot mobility by humongous gas mask carriers. Notice their "Combat Light" Soldier gear set-up with a SMALL gas mask carrier.

3. Live Combat Light Package at your buttpack

a. Army standard NSN 8405-01-416-6216 Eco-Tat Lightweight Sleeping Bag Multi-Purpose LWSB-MP (3.0 lbs)

b. Army standard NSN 8405-00-290-0550 Poncho with 550 cords to be a poncho-tent, hood tied into a knot (1.3 lbs)

c. Army standard NSN 7210-00-935-6665 OD Green space casualty blanket (0.6 lbs)

d. Army standard NSN 8415-01-228-1312 ECWCS Gore-Tex jacket (1.5 lbs)

__________________________________

6.4 pounds TOTAL

See:

www.rangerjoes.com/catalog/selection.cfm?category=main&id=892

That's it.

This is all you need to survive from the elements from freezing to 100+ degrees. Items b-d fit inside your buttpack or inside the Ecotat LWSB Multi-Purpose's stuff sack. Item a, the LWSB-MP straps on top of the buttpack or directly to your LBE rear and acts as a kidney pad or stuffs inside it. The weight you save by not carrying even the empty ALICE rucksack (6 pounds) essentially "pays for" the Live Light Package at your buttpack. Why carry 6 pounds of volume when you can carry instead 6 pounds THAT DOES SOMETHING FOR YOU; ie; allows you to live comfortably (YES!) in the field?

Live "Combat Light" in Closed terrains

If you are moving and it begins to rain, you put on your waterproof, but breathable GT jacket, otherwise you sweat in your brush-breaking BDUs and hopefully dry out by night's end. GT jacket also acts as windbreak, but must be treated with McNett.com water repellency Revivex treatments to remain effective. The GT jacket extends down far enough so that only a small part of your legs are uncovered but while you are moving these large muscles are getting hot so they will dry off any rain/dew on vegetation contacted so the GT pants are not needed.

How can you compress the GT ECWCS jacket so it can fit with the other Combat Light items?

Compress the GT jacket with a clear plastic vacuum bag from www.spacebag.com so it takes only a small part of the space inside your buttpack.

At night's end and you become stationary; you find two trees or bushes and tie your long poncho-tent cords to stretch them out. Cut branches to act as tent stakes and mash down into the ground. You now have a rain and wind break; 15 degrees of warmth gained. Unfold mylar blanket shiny side up to reflect your heat back to you (about 15 degrees F) so its not lost to the ground via conductivity and stretch out inside your poncho-tent as a floor.

Open up Ecotat LWSB-MP, pull over and around yourself; you can keep your boots on if you want---tighten shock cords around your feet above boot soles to keep mud out from inside your LWSB-MP. Close head shock cords to trap further heat and go to sleep, drying out your BDUs by the morning. Or if the situation is less threatening, remove your boots and socks and close lower end of LWSB-MP around bare feet for restful sleep. Use GT jacket as extra insulation or pillow for head by stuffing into unused LWSB stuff sack.

If you are in a 2-man fighting position (square hole in the ground to evade enemy observation/fires) and not on watch, unzip LWSB-MP so its a poncho-liner-like blanket (but warmer) and open head hole and stick head through it. Curl up and go to sleep but with weapon at the ready. If you have to go into action you are ready to shoulder weapon and return fire, to include running---you are not caught zipped up in a sleeping bag.

Combat Light in Open Terrains

The only variation is that in open terrains you don't have trees to tie your poncho-tent lengthwise cords to and material to cut stakes from, so you carry 6 tent poles and 6 x OD green plastic tent stakes---the stakes in your buttpack and the poles tied together into one unit attached to the LWSB-MP's stuff sack or on top of the buttpack.

You live the same as you would in closed terrain except that you erect 3 poles in front and 3 poles in the rear of your poncho-tent to erect it and let the tension from the stakes pulling on the cords to keep the tent standing.

Other benefits:

If you become a casualty, the mylar space blanket, LWSB-MP available on your person can be placed around you by a Combat LifeSaver so you stay warm to not go into shock and die. The poncho can be used to drag you like an expedient SKEDCO type MEDEVAC aid for 1 person rescue. Shiny side of mylar casualty blanket can be used as attention getter for rescues or aircraft recognition/marker panel for Close Air Support.

4. Hygiene Combat Light

Also in your buttpack would be a VERY SMALL HYGIENE KIT in zip-lock plastic bag:

e. 2 pairs wool socks rolled up with small can foot powder

f. disposable razors with handles cut

g. small travel toothbrush or one with handle cut

h. small bar of soap

However, if the U.S. Army got smart, it would mold on the back of the MRE plastic spoon a toothbrush and rails to accept shaving cartridges (Spork Toothbrush Shaver) and supply a small packet of multi-use soap Soldiers wouldn't even need to find a "PX in Afghanistan" to obtain/carry the items described above except for the socks/foot powder.

Learn to shave with just water from your canteen cup, until then use soap for lather. In worse case scenario, you can clean teeth with wad of toilet paper from MRE and rinsing water in mouth.

Quick-Detachable Buttpack to carry the "Combat Light" Module

The following pictures show how you can rig your buttpack so it can be quickly attached or detached from the rear of your ETLBV or LC-2 Load Bearing Equipment (LBE) fighting load. You would have the option of jumping the buttpack with Combat Light module INSIDE your rucksack so you do not have a bulge at your rear in event of the likely rear PLF. However, at first opportunity you can in a matter of seconds clip the buttpack to the back of your LBE without fumbling around with flimsy ALICE clips and shed your rucksack at a cache point or into some form of unit transportation.

Anchor the female buckles of a pair of Blackhawk sternum straps to the buttpack

Anchor the Blackhawk straps' male ends to the pistol belt on the ETLBV or LC-2 LBE

Route a strap with or without buckles to secure top of buttpack to ETLBV

Of course, you could jump your buttpack attached to your LBE back and at first opportunity stuff the LWSB, poncho-tent, casualty blanket inside or strap them as a unit inside the LWSB stuff sack on top of the buttpack, leaving space inside for NVGs, a thin inslation layer of clothing like the field jacket liner or Brigade Quartermaster "Bivvy Wear Packable Thermals" proven recently by British Soldiers in Afghanistan since the current ECWCS insulation layers are too bulky and heavy to be carried along in a buttpack for staying warm after a long day's march.

Another good, larger buttpack that can be used is the SpecOps Brand "SOB" described on the link below:

Problem: Soldier's have depended on Buttpacks for years. In theory, they are an excellent method of carrying much needed gear low and close to the body. Problem is, when they are attached to military web gear, it is nearly impossible to access contents without the aid of a buddy, or worse yet - removing your entire set of web gear. This wastes time and unnecessarily puts the Soldier at risk.Solution: S.O.B. - Soldier's Optimized Buttpack. A workhorse built for the modern warrior: the modernization of an old standard: the Buttpack. This S.O.B. has 3 compartments with zippered entry to allow the Soldier instant access to critical gear while on the move. No more straps and flaps to fool with. The need to remove web gear or ask for assistance is gone. Larger, more rugged than conventional Buttpacks, this S.O.B. means business!

Features and Benefits of the S. O. B. :

Constructed from 1000D Cordura(tm).

Main body compartment has white 'DURA'-panel liner: provides added water resistance and increased visibility of contents.

Multiple gear loops for additional gear attachment points (works well with the X-System from Spec.-Ops. Brand).

No exposed stitching along seams.

Fully seam-taped interior, double needle stitched.

Dual side pockets with grommet drain holes allow the Soldier easy access on the move.

3 zippered compartments: main body compartment has "storm-fly" zipper cover for extra element protection.

4 welded mil.-spec. 'D'-rings for attachment to military web gear.

Carry/hang handle.

Color: Woodland, Olive Drab and Black.

Dimensions: 14" x 11" x 6"; 930 cu. in.

Retail Price - $49.95

Guaranteed for life, MADE IN TEXAS, U. S. A.!

5. Fighting Combat Light

a. One E-tool per every 2-man buddy team because only 1 can dig at a time while the other provides security and it must be on his ETLBV not his rucksack!

E-tools are parachute jumped on the rucksack for safety reasons. When rucksacks are ditched at the cache point or transported by air/ground vehicles the e-tools are removed and placed inside the buttpack top. Men with e-tools are these with M16/M203 grenade launchers that cannot attach a M9 wire cutter bayonet as currently configured. Same men also have a Leatherman or Gerber multi-tool type utility device to make up what was lost by not having a M9 WCB.

b. MOPP Gear should be in a modular roll that can be attached to the top of the LWSB-MP or if there is no threat kept with rucksacks which would have individual name/unit markings so if used as collective LOGPACKS can get the right sized MOPP suit/boots to the right Soldier.

c. Extra BDUs: are un-necessary; one set on your body can easily last 1 week or more. Dry out during the night in your poncho-tent. Even then extra material should be removed to improve cooling and shoulder sleeve pockets added.

d. Individual Fighting Gear sublimation: the two canteen covers on your ETLBV should be covered, multi-use pouches and the canteens themselves flexible, collapsible so if they are emptied of water can be stuffed in the buttpack and the pouches used to carry AMMO, grenades etc. for firefights. All M16/M4 magazines with pull cords to clip onto a snaplink to not get lost when emptied in a firefight.

See: www.combatreform.org/canteencover.htm

Two field pressure dressings taped to stock of weapon for entrance/exit wounds and to act as "cheek weld" for firing positions. Camel-Bak on your back puts 70 more ounces of water available on the move, and should have a purification filter so any water source can be used to pump fill the reservoir and the two 1 quart canteens. Night Vision Goggles or Binos held in chest pouch worn over top of body armor. Every Soldier with red lens small neck chain Photon fingertip-sized flashlight for map reading and general visibility if needed at night not large, bulky G.I. anglehead flashlights. Natick Stove/Canteen cup in your rucksack for parachute jump, transferred to your LBE for water boiling/hygiene at first opportunity.

See: www.combatreform.org/hotdrinks.htm

e. Unit Mission Gear sublimation: ropes, radios & batteries, claymores, MG spare barrel bags with tripods, Combat LifeSaver Bags etc. whenever possible are carried on back of designated Soldier by their own carry straps, avoid requiring the rucksack to carry FIGHTING LOADS; rucksack should be LOGPACK with generic extra supplies, and even then as a packboard is best configuration to carry heavy dense ammunition. The packboard shelf should be able to carry a wounded Soldier like Kifaru's cargo chair does.

6. Train Combat Heavy and Combat Light

www.youtube.com/watch?v=hTVRyLVwYhM

www.youtube.com/watch?v=hTVRyLVwYhM

We need to grow up and start taking war seriously which means every time going to the field carry actual live ammunition so we are carrying realistic loads so we don't use up rucksack volume with field living comfort gear done badly and having the trust and confidence that we treat our Soldiers like professionals so they return the ammo at exercise end and not go "postal". If we are not there yet, then we damn well better develop some actually-weighs-the-same-as-live-ammo DUMMY (cannot kill anyone) AMMO, grenades, bullets, rockets, missiles so we can train realistically as we should fight.

7. Test for Combat Heavy not Sports Illustrated

The current sports t-shirt, shorts and running shoes APFT should be junked in favor of a 6 mile march for time with full combat equipment; rucksack, LBE, basic load of ammo, helmet, BDUs, boots. If we can achieve 4 mph with "combat heavy" loads with rucks on our backs, then when we cache the rucks we should be able to go 4-7 mph "Combat Light".

LONG-TERM SOLDIER'S LOAD FIX

8. Future TA-50 Gear decided by Board of Soldiers not "Council of Colonels"

A "Council of Colonels" meets to decide gear for us grunts for the SEP program to "type classify" (tested to "perfection" to be declared Army kosher) when it should be the lower-ranking gear gurus who are actually humping (carrying) the machine guns, rockets and mortars from every Army command representing their specific climes/places/missons. This is why a lot of our gear sucks. Most Colonels I've run into are concerned more with form than function and are not technotactically oriented enough and candid. SGTs, LTs and CPTs should decide on our new gear from actual try-it-themselves testing.

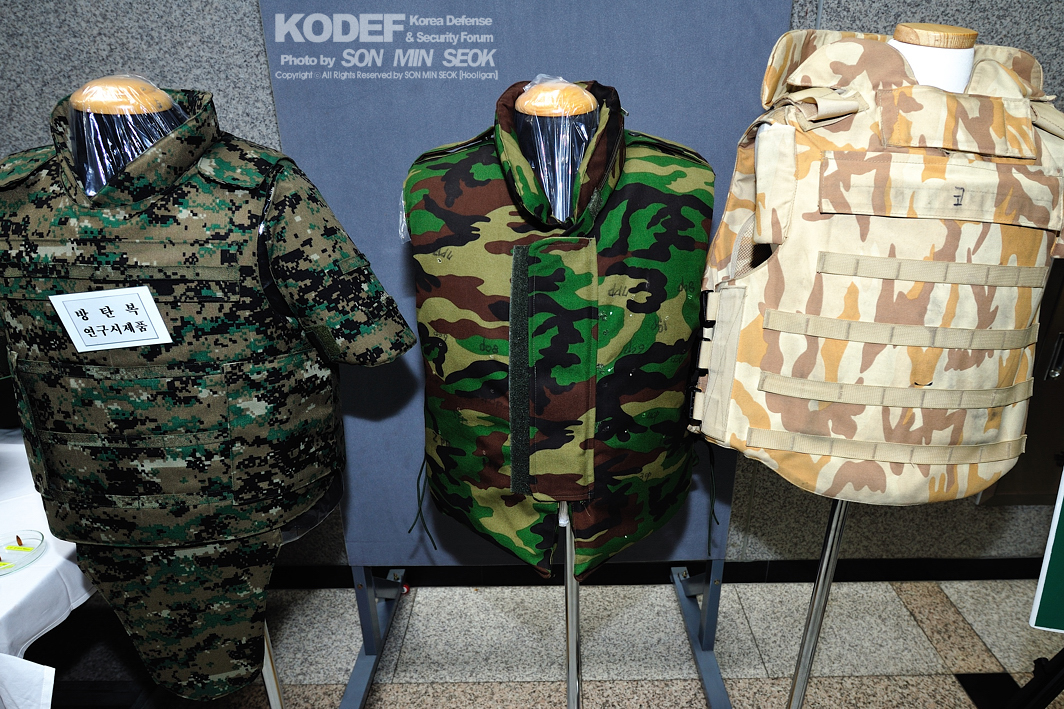

The expertise of the natural "gear gurus" should be tapped and have them designated as a "Master TA-50 Specialist"---an additional skill identifier (ASI). These gear experts would go to Natick Labs and be school trained on the proper fit and wear of ALL Army equipment and have field living (Level "C" survival skills) taught to them so they can advise Commanders that a hot weather desert boot is NOT a mountain boot and how to properly size Soldiers for body armor so a bullet doesn't sneak by and kill them. The Army's Master TA-50 Specialists would also train the Soldiers in their companies how to wear and maintain their TA-50 as well as be pro-active about getting better gear. The Army is strangely an organization that goes "camping" yet hasn't trained itself how to "camp". Lay on top the need for combat mobility 4-7 mph which requires smart loading and constantly improved equipment, its clear that a Soldier from every Company in the Army should go to "gear school" to become a Master TA-50 Expert. To fund this we should cancel the un-needed lav3stryker deathtrap armored car purchases and upgrade superior tracked M113A3 Gavins into "IAVs" for the IBCTs and Light unit's Delta weapons companies and AT platoons since they can be parachute airdropped and airlanded by Air Force C-130s safely for long distances and flown by Army CH-47D/F helicopters for short distances and be fully autocannon and RPG protected. Call them tracked IBCTs or "Gavin Brigades".

An Army bureaucrat informs us that Company Commanders can buy with unit funds whatever gear they need for their men from the GSA Catalog and CTA 5900 (not Army "type classified" but available for purchase: "good enough" using Army funds) but this is something that's not pro-actively done and known about. Have you ever heard about this? GSA catalog is on CDs Supply Sergeants have so it takes a bit of looking when it should be on the www for all Soldiers to see.

What we need is a Soldier's Board of lower ranking gear experts who will review new gear, get it on the GSA Catalog/CTA 5900 and then publish an annual focused list throughout the Army encouraging Commanders/units/individuals to buy these items. Apparently its ok for units to fund-raise to build up a unit fund or this purpose, too so not having the money is not an obstacle. This list of authorized field gear on GSA/CTA 5900 should be placed on the Army Knowledge Online (AKO) secure web site so any Soldier can see what the Soldier Board recommends they get ASAP.

Every year, every Major Army Division (Airborne, Air Assault, Light, Mechanized, Armored etc.) and separate unit (2nd ACR, 172nd Arctic Brigade, SF, Rangers) has ITS SOLDIERS select by vote a field gear representative who will travel to Fort Benning, Georgia to decide for the rest of the Army what off-the-shelf Soldier gear to buy and what gear to develop. Every unit has at least one "gear guru" right for this job; a pro-active Soldier who studied field gear and on his own tinkers and tests what works and does not. THE CHAIN OF COMMAND DOES NOT SELECT THE GEAR BOARD SOLDIERS. Some out-of-touch Army General does NOT select some political yes-man to be on the board to keep the troops ill-equiped and "in their place". Some DA civilian with a ponytail going through perpetual mid-life crisis does NOT decide what items are bought or developed, THE SOLDIERS DECIDE. No "Council of Colonels". Its the individual Soldier's lives that are at stake not some bureaucrat in a comfy office with one retirement already under his belt longing for the good 'ole days when the equipment they had sucked and everyone liked it. What the Soldier TA-50 Board decides AUTOMATICALLY become AUTHORIZED Soldier optional wear/use items without the current kill-joy, politically correct "uniform board" having one say in their decisions. They do a great job keeping everyone miserable and without esperit de corps during garrison hours; the field Soldier's attire should be guided by FUNCTION decided by the mud-Soldiers. Each year a list of acceptible alternatives will be decided on by the Board for Soldiers to buy/use on their own option. Each year the board will decide on commensurate with the SEP budget what items will be bought/issued to enhance Soldiers immediately. And each year the board will see what industry and Natick Labs have "cooking" and provide feedback.

Summary/Conclusion

The U.S. Army should IMMEDIATELY---THIS MEANS RIGHT NOW DAMN IT--PURCHASE AND ISSUE ECO-TAT LWSB-MPs, MYLAR CASUALTY BLANKETS AND BUTT PACKS TO EVERY COMBAT ARMS SOLDIER TO SOLVE THE SOLDIER'S LOAD EFFECTIVE IMMEDIATELY. THEY ALREADY HAVE PONCHOS, JUST NEED TO ATTACH THE NEEDED 550 PARACORDS TO THEM.

Next, 3 weeks of Basic Training BS harassment games should be replaced with 3 weeks of in the field survival training by sending trainers to U.S. Army SERE Level "C" school at Camp MacKall, NC and then having them take-over the last 3 weeks of every cycle's training before graduation. Designated "Master TA-50" gear experts in every Army Company would also be sent immediately through SERE school and Natick Lab training to advise commanders/units and meet annually to determine the direction of Army SEP and R&D efforts.

The APFT needs to be changed to a "Combat Heavy" ruckmarch for time and from now on the Soldiers who actually carry gear into battle decide what gear is bought and how new gear is developed with ruckframes that become all terrain carts and folding human and electric powered bikes fielded in experimental light units as DoD Advanced Concept Technology Demonstrations (ACTDs) to quicken those dismount-centric units that will optimized to hold lodgments and move through the most restricted terrains and not be supplied with a high-technology, stealthy, band-tracked, C4I digitally-connected, air-transportable Air-Mech-Strike armored fighting vehicle (21st century tanks) that other mounted-centric units acting as shock action suppliers for mobile warfare through less restricted terrains should have.

Rethinking SLA Marshall's The Soldier's Load and the Mobility of a Nation (SLAMOAN)

The Soldier's Load and the Mobility of a Nation (SLAMOAN) is Marshall's most important book yet its also his most ignored. The book has two main ideas and one minor one.

Main Ideas

1. Soldier's Loads must be less than 1/3 his body weight so he can fight with the most biomechanical and psychological power on his feet, fear eats away at load-carrying totals in war

2. The mobility of the nation's war machines makes it possible for the Soldier's Load to be carried by them so he can be light on his feet

Minor Idea

That in event of ammunition resupply being cut-off from the nation-state war machine pipeline, ammo will be shared, taken primarily from the cowards who don't fire their weapons by those that do.

Of these ideas, SLAM is right on the first idea and wrong on the others. However, even on the first idea, he has failed to fix the American Army and marines Soldier's Load habits because of entrenched cultural narcissistic mentalities that he did not adequately attack and demolish.

Data versus Ego

SLAM argues in the book that whatever the great captains said about what was vital to carry by the Soldier should be over-ruled by DATA and FACTS drawn from EXPERIENCES. He misses the mark because its not just the officers who insist on overloading Soldiers because they think we are supermen, the enlistedmen themselves think they are supermen and it only gets worse once they start to get killed. An air of self-righteous victimhood is taken on by everyone involved. If you propose less weight be carried YOU ARE ACCUSED OF BEING A WEAKLING "pussy". SLAM also falls short of proposing TANGIBLE SPEED GOALS we need and the maximum weights for them that are possible. Without SLAM holding the Army to TANGIBLE mobility goals they can dismiss everything he says weight-wise as he's just being a "pussy", I CAN ROUGH IT (ICRI) syndrome etc. remaining the operative groupthink. So immobile, overloaded Soldiers are what we have today despite SLAM's book.

SLAMOAN is welcomed by lemming narcissists outfits like the USMC because it foists the lie that all the individual has to do is be a dumbass and subliminate himself into the organizational "borg" and all his ammunition, food and water needs would be met. According to SLAM, he could and should trust the organization to carry his rucksack for him by trucks and they will always get through to him. It took me a case of rain-soak-created hypothermia in the USMCR to teach me to not trust ANYONE to carry my rucksack holding life/death dependent warmth gear in sub-zero temperatures in Wisconsin. To ASS U ME that some mommy/daddy organization is going to take care of you in the face of enemy opposition is asinine. LCPL Jason Rother and thousands of others have paid for this naive outlook with their lives.

Disaster at Dien Bien Phu: Where was SLAM in 1954?

SLAM misses the "big picture" of the grand strategy and strategy of war. Nation-state wars are NOT the only form of conflicts, there are sub-national conflicts where THE INDUSTRIAL CAPACITY OF THE ENTIRE NATION-STATE IS NOT, REPEAT NOT GIVEN OVER TO RAIN SUPPLIES UPON FIGHTING MEN. The French in IndoChina had to make-do with WW2 left-overs from the Americans to fight a NON-LINEAR war without fixed fronts where there would be "safe" areas in the "rear" to run wheeled trucks up/down roads to resupply fighting men as SLAM retells again and again in SLAMOAN. SLAM ignores non-linear, sub-national conflicts and his entire construct to get weight off the individual Soldier collapses.

Thus, the French Paras entered the Dien Bien Phu valley overloaded and were soon cut-off from air resupply by VietMinh anti-aircraft guns. Sharing of ammo between shooters and cowards did not save them, either. They ran out of ammo. Next, SLAM's model of the lemming infantry "ant" was killed by "raid" artillery smashing its nests (forward operating bases) . So what was SLAM doing in 1954 when all of this was happening?

He certainly wasn't amending his thinking and his writings which continued to sing the praises of reliving WW2's total war footing inundating troops with supplies on mythical linear battlefields where they can easily reach them. SLAM contradicts himself constantly by saying tracked amphibious vehicles can carry the Soldier's load so he's light on his feet then says their development is not important, clearly he's confused since he lists them as needing roads when even in WW2 LVT-4 Alligators were cross-country mobile to be wherever the infantry wants to go. Thus, SLAM misses the ultimate solution to the Soldier's Load problem: having every Soldier embedded into a M113 Gavin light armored tracked tank THAT HE CAN SEE AND TRUST TO BE THERE BECAUSE IT IS THERE WITH HIM.

So How Do We Solve the Soldier's Load for the Non-Linear Battlefield?

Clearly, SLAM's "killer ants" that infest an area slowly on foot, supplied by "hives" is easily smashed by long-range artillery "fire beetles" since we in the west are not going to out-ant number Third World Countries in total war mobilization let alone limited wars where civilian life continues unabated. Using the insect kingdom as a model of efficiency what we need are:

21st Century Ground Army

Killer Bees

Killer Beetles

Killer Super Soldier Ants

Killer Nests

Killer Nest Flyer

Killer Bees

High overhead, the Killer Bees are STOL observation/attack planes owned and operated by the Ground Army that accompany them as they move from BATTLEBOXaircraft containers towed by the Killer Beetles; portable nests that exploit the ground for protection by burrowing.

Killer Beetles

The Killer Beetles are tracked TANKS that move the Killer Soldier-Worker Ants cross-country to include across water under a protective shell that can also stop and burrow to exploit the ground for protection. EVERY Soldier has at the minimum a M113 Gavin light armored track to move him at 60mph on roads and preferably cross-country with stealth and 30 days of supplies with complete armor protection. While in the FOB, beetles with long-range tube and rocket artillery insure the "hive" isn't demolished in a replay of the French Paras at Dien Bien Phu and nearly happened to our dumb marines at Khe Sanh.

Killer Super Soldier Ants

First, state our dismounted mobility levels and the maximum weights possible and stick to them. 4-7 mph for 20 miles should be the goal. Next, create self-sufficient troops that have SERE skills and lightweight equipments that will supply them water and climate-protect them against the earth WITHOUT NEED OF A RUCKSACK. The rucksack is the individual Soldier mobility killer. Rucksacks should be carried on/in the Killer Beetle M113 Gavins and when they can't on bikes/carts or rolled on their own wheels. He must be ready to shoot enemy ammo and weapons as captured. We must carry ALL of the ammunition and equipment you'd take to war NOW. Learn to live "combat light". The rucksack is a "LOGPACK" that can be passed to the FOB for filling up with supplies but not be seen as individually owned and kept. It has wheels to roll for hands-free towing whenever possible. Non-able bodied, wounded Soldiers can be towed on carts and bikes and SKEDCO plastic sheets. Bikes and carts enable dismounted and unarmored mounted maneuver away from the Killer Beetles as required.

Killer Nests

The Killer Bee/Killer Beetle/Killer Soldier Ant Force can operate for 30 days using trailer-towed supplies. For long-term operations a hardened FOB "hive" constructed of ISO container BATTLEBOXes can be linked together in myriad ways to form walled perimeters filled with dirt for hardening, buried underground etc. while holding vast amounts of supplies and protecting the Killer Bees/Killer Beetles/Killer Soldier Ants themselves. Power from wind and solar as well as water from the ground and/or ambient air are collected on the Killer Nest pods so only the minimum of fuel and ammunition has to be resupplied in some flow to the hive. There are no huge supply dumps languishing everywhere; the supplies start life in the Killer Nest pod and travel all the way to the FOB hive for use.

Killer Nest Flyer

To fly the Killer Beetles or Killer Nest modules would be a STOL/ESTOL/VTOL aircraft that would enable 3D maneuver against the enemy, escorted by the Killer Bees in the air. The Killer Nest Pods are LTG Gavin's KIWI pods concept finally fulfilled.

www.youtube.com/watch?v=XKeCVYTiIWg

www.youtube.com/watch?v=XKeCVYTiIWg

INTRODUCTION

Of the two score military books and manuals which I have written, this essay which first appeared in 1949 has had by far the most instructive history and consequence.

I was therefore delighted when the publishers of the new edition agreed with me that its genesis and aftermath must be made part of the story.

The basic theme is elementary and should be beyond argument: No logistical system is sound unless its first principle is enlightened conservation of the power of the individual fighter.

The secondary theme, in 1949 a radically new idea, as yet unsupported by incontrovertible scientific proof, is that sustained fear in the male individual is as degenerative as prolonged fatigue and exhausts body energy no less.

Today, this second proposition is commonly accepted in medical and military circles. As to the first proposition, we are doing better and everyone gives it lip service. But there remain too many jokers down the line who still haven't gotten the word.

About the evolution of the essay, and as to the course I ran, I am reminded of the Irishman whose horse ran last in a field of sixteen. When the animal finally passed him, he leaned over the rail and whispered: "Pray, what took you so long?" In July, 1918, I marched with my Regiment to the front on a balmy, starlit night and was astonished to see the strong men around me virtually collapse under the weight of their packs when we got to the fire zone after an 11-mile approach on a good road. They had been conditioned to go 20 miles under the same weight in a broiling sun. Then some days

Page iii

later, after our bath of fire and burials were done, we shouldered the same packs, marched rearward 32 miles in one day and got to our billets with no sweat, feeling light as a feather.

I should have seen the lesson then. But to my juvenile mind the experience signified only that it is a lot easier to move away from a battle than to go into one, which any fool knows. Many years went by. Then in the Pacific War in I early 1944, Major General Archibald V. Arnold gave me a tactical problem to solve. He wished to know why it was that in the atoll operations, if troops were checked three times by fire, even though they took no losses and had moved not more than a mile, their energy was spent and they could not assault.

As is fully explained in Men Against Fire, I was able to advance a tactical solution for the problem, though I still could not answer his question. The mystery grew until it haunted me.

Then after Omaha Beach, as is described in this essay, I dealt with companies whose battle experience had variously gone the whole gamut from utter defeat and mass panic to preserved order under heavy pressure, and distinguished achievement. When at last my field notes were complete, they said to me that there was one truth about the nature of fear which men had missed through the ages. Still, I hesitated to speak.

In 1948 I raised the question with my personal friend, Dr. Raymond W. Waggoner, chief of psychiatry at the University of Michigan and a sage in many fields. He was at first skeptical about the theory and s.aid that the physical effects of fear and fatigue

Page iv

might seem to be the same but he believed that the rebound from fear would be more rapid. When I stood on the documentation, he called in some of the biologists. They rallied to my side of the discussion, one of them saying: "We have been thinking along these lines for some years." After hearing them out, Dr. Waggoner warmed to the subject, gave me a private lesson in bio-chemistry and imparted the confidence which enabled me to proceed.

Since I am not a scientist, the organic reaction to fear is not a proper part of this statement. Such details do not stay in my mind and those who are interested in them have a plethora of learned writings to ponder. We simply found out that we were on the right track. After the theory was launched, medical laboratories in several of our main universities took it under study, and by varying tests proved it to be correct. One of them, I now recall, made its findings by examining men undergoing major dental surgery, as to the count of male sex hormones excreted through the urine before and after. Still later, during the Korean War, one of the research organizations serving the Army put scientists into the line to make comparable tests of fighters before and after combat, with general results, as I recall, doubly confirming what had already been substantially proved.

At about the same time there was a study in the University of Utah for some months to determine how long this truth had been kicking around underfoot; that is to say, that all of the basic evidence was in the hands of scientists, but none had bothered to add two and two to make four of it. I think these researchers concluded that there was no excuse for

Page v

ignorance after the year 1890. If that's the wrong I date (or the wrong school) it's because I kept no file on the business, feeling no interest in the experiments.

What is said in the essay concerning optimum loading the Army took seriously. One Army board set up its own test apparatus, complete with treadmill, etc., to measure human stress under assorted, loads at varying distances. The Quartermaster Climatic Research Laboratory ran other parallel tests and published reports of same which continued into the late 1950s. The opening paragraph of the first study acknowledged that the research had been stimulated by this essay. From that same writing by Dr. Farrington Daniels, Jr., M. D. I quote only these words: "It is disturbing to speculate that since 1750 several hundred million men have gone into combat on foot carrying back loads, while during this time probably less than a hundred men carrying loads have been subjected to scientific study."

Programs were projected for lightening all line items which the infantryman must carry into battle. What came of all this motion in the end I cannot say.

Completed data often may point to the existence of a pressing problem, but within a bureaucracy thousands of minds must be in tune to evolve the technical solution affording the bettering of a system. As Admiral A. T. Mahan said, this is the great evil.

In Korea, when the scientists were double checking the laboratory data, I was viewing off-and-on the same problem in quite another dimension, and going on to a startling tentative conclusion. Here was a unique battlefield. With its high, ubiquitous ridges,

Page vi

limited foregrounds, climatic extremes and short duration fire fights, Korea gave us the best opportunity to measure combat stress that we will ever know. We took little advantage of it.

My field notes convinced me that we need to take a fresh look at the recovery interval which follows troop exhaustion. Man is better than we know; his tired body will rebound quicker than we think.

Take one example. After a wearing approach march and entrenching, two rifle companies went into perimeter on adjoining ridges. They were the same strength; the positions were about equal. Both units were dog tired. One commander ordered a 100 percent alert. The other put his men in the sacks and with a few of his NCOs kept watch. Thirty minutes later the Chinese attacked. The first company was routed and driven from its hill immediately. The second bounded from its sleeping bags, fought like tigers and held the position until finally ordered by battalion to withdraw.

Another incident is described in detail in The River and the Gauntlet. One company of the Wolfhound Regiment was flattened when overrun by a Chinese brigade. The unit looked utterly spent. The brigade charged on to take position atop a ridge blocking the route of withdrawal for the regiment.

The stricken company, after one hour in the sacks, was ordered to take the ridge. Even before the ascent started, every company officer was felled by fire.

Without a break the survivors swept the slope and carried the crest.

If these episodes mean what they say, then some of our security procedures when in the presence of the

Page vii

enemy need to be re-examined. Worn out men cannot fight or think. It is folly to press them beyond endurance when just a little rest will work a miracle of recovery.

A collateral proposition is best illuminated by citations from marine operations. When the 7th Regiment emerged on the Koto-ri plateau in November, 1950, it was met with bitter cold and the first spark of enemy resistance simultaneously. Returning patrols showed every symptom of men in intense shock.

Pulse rates were abnormally low. The individuals gibbered, grimaced vaguely and could not articulate.

The puzzled doctors treated the empirically with a heavy shot of grog and bed rest. Eight hours later, they were normal.

On the other hand, the remnants of the 7th Division elements, which 1st marine division brought out over the ice of the Chosin in an heroic exploit, had been enveloped by the enemy for the greater part of one week. The cold, the privation and the suffering at the hands of the CCF had been extremely harsh throughout. In the case of these men, Major General Oliver Smith felt that at least 48 hours total rest was essential. At the end of that time, he concluded by personal inspection that the ones which I had escaped wounds and frostbite could march out with the column from Hagaru-ri and do normal duty.

There is only a suggestion here that the recovery period is in ratio to the duration of the extraordinary, pressure resulting in exhaustion. Appearances are not to be trusted. The unit knocked out by five hours of marching, digging and hard fighting may look no less down and dispirited than the unit saved after three

Page viii

days of envelopment and hand-to-hand combat on a hilltop. It does not follow that what the two require for recovery is at all alike. This subject requires far more attention than anyone has yet given it. There is more to be learned about man under pressure than we yet know and the areas for, profitable research which remain unexplored are wide indeed.

One trouble is that we are slow to alter our procedures even after ordeal by fire has shown where they are at fault; this is due to the drag of orthodoxy which is a quite different thing from tradition. Another difficulty is that the practical lessons that we learn in war and apply under the gun are too often obscured in the pursuit of some other object under the conditions of peacetime training.

Two anecdotes, both dating from 1956, both bearing directly on the thoughts expressed in this essay underscore my meaning. Israel's Army is exactly as old as is this small book. Right after publication, that Army translated the book into Hebrew and made its principles a part of operating doctrine for all troop leaders.

In the book Sinai Victory you will find this tale. Israel's general campaign into the Sinai wastes was to begin with a battalion attack on Queisima, not far from the oasis called Kadesh Barnea in the Bible.

H-hour for the whole campaign was determined by an estimate of when this troop body would close on the position. But the night advance through the dunes and into the wadis was a killer and the men staggered and stumbled. As the battalion got to within strike range of the target village, the Commander's watch told him that he was still on time but his eyes saw

Page ix

just as clearly that his men were spent. He could not get in touch with the High Command by radio. Even so, he made the decision to postpone for one hour this triggering assault while his men lay down in the sands in their great coats and slept.

The contrasting episode occurred at about this same time. I had flown via Naples to join the Israeli Army in the Sinai Desert. Over a weekend I was with the Sixth Fleet off Sicily. On Monday, there was to proceed a two-battalion exercise, an attack by marines on Sardinia, with the Navy doing its part. That Sunday morning, we gathered on the flagship and with Admirals Walter R Boone and Charles R. (Cat) Brown present, the full-dress briefing prior to attack perforce went as smoothly as a Broadway musical in its second year.

At the end, Admiral Boone asked: "Any questions, General Marshall?" I said: "Yes, one question. As I get it, the battalion attacking just after dawn gets in landing craft four miles out. The beach is defended at the waterline by about two companies, working heavy mortars and machine guns, along with small arms. Their bunker line is along that low-lying ridge 700 yards inland.

The battalion will take that by mid-morning. It will then go on to that first high range, marked 1,500 meters, where the enemy artillery is based. By sunset these same men are supposed to assemble on the range beyond that one where they meet the battalion coming up from the west coast. Now have you told the troops that if this were war they would be doing well if that first line of low ridges were theirs by the end of the day?"

Page x

Boone was startled. He said to the two marine commanders: "Is it true?" They withdrew to consider the question, then returned to say: "We agree with him."

Boone asked: "Then why are we doing it this way?"

Someone replied: "Any smaller plan wouldn't give forces enough of a workout."

I said: "Fair enough. But you have not answered my question. Have you told troops, staff and everyone else that the plan is far over-extended,- that operations would not have this much reach if men were fighting?"

The answer was: "No".

I said: "That's the hell of it. No one ever does. Out of such plans and exercises in peacetime, when no precautionary words are spoken, we recreate our own myths about the potential of our human forces. Then when war comes again, men who discovered the bitter truth the hard way are all gone. Voila, we've got to learn all over again."

There is only one way to stop such drifting. Realistic training derives only from continued study of what happens in war. No system can go far wrong if leaders at every level know what is to be expected of their people under fire and are prepared to raise practical questions when planning staffs overlook elementary precautions. The first duty of the officer is to challenge whatever seems illusory.

The marine corps has a classic model on which to guide. As the analyst of General Smith's operation in the frozen north, I have long felt that its salient lesson is the Commander's deliberate conservation of

Page xi

his men's powers under utterly adverse conditions. Though the enemy vise steadily tightened, he still rested his troops till he felt they were ready to march and fight. Each day's movement was regulated by his measure of how far the column could go, short of exhaustion. Of this care, came the big payoff to him and to his people. At Koto-ri, after the hard day's fight, he felt worn down. Then outside his tent he heard some truckers singing the marine hymn and his heart leaped up. He had earned that great moment. A more precipitate, but less bold, leader would have started lunging from the hour when Hagaru-ri and Yudam-ni became enveloped and, 1st marine division would never have come down the mountain to the sea.

S.L.A. Marshall

Brig. Gen. USAR-Ret.

Dherran Dhoun

Birmingham, Michigan

CONTENTS

PART I: THE MOBILITY OF THE SOLDIER Page 1

PART II: THE MOBILITY OF A NATION Page 77

Page xii

PART I: THE MOBILITY OF THE SOLDIER

ONE-MAN LOGISTICS

STRATEGY is the art of the general. And like any other art, it requires patience to work out its basic concepts. But the odd part of it is that among higher commanders that branch of the art most apt to be treated with a broad stroke, though it calls loudest for the sketching-in of minute details, is the logistics of war.

Since that word has in recent years become a catchall, covering everything pertaining to the administrative and supply establishments, it is necessary that I be exact as to how I use it here. Let us therefore take the definition of Sir George Colley, who described logistics as "the scientific combination of marches, the calculation of time and distances, and of economy of men's powers." This is much more satisfying than anything to be found in our own dictionaries.

But when that last phase is included (and it cannot be left out) it precludes that view of logistics which sees it

Page 3

only as a game for the G-4s and the mathematicians-a game to be settled with loading tables, slide rules and transportation schedules.

Logistics becomes, in fact, the very core of generalship -the thing that is ever the main idea-to get military forces into a theater of war in superior strength and husband that strength until they shall prevail. Further than that, I think we can all agree this does not mean numbers of men and weapons solely. For if it did a general would be only a glorified cattle drover, and we would say of him what Col. G. F. R. Henderson wrote of General Pope: "As a tactician, he was incapable. As a strategist, he lacked imagination. He paid no attention to the physical wants of man or beast" . With the general, as with anyone under that rank, the very acme of leadership comes of the ability to lift the powers of the average man-in-the-ranks to the highest attainable level and hold them there. It is therefore especially curious that there is less competent military literature on this subject-the economy of the powers of fighting men-than on any other aspect of war.

In modem armies, more is being written about moral value than in the preceding nineteen centuries. Yet modern works on the art of command have almost nothing to say about the economy of men's powers. It seems to be taken for granted that the introduction of the machine into warfare is tending to produce automatic solutions of the prevailing problem of how to get more fire out of fewer men. But that can only be true if men's powers before and during battle are more carefully husbanded than they have ever been. The actual fact is that men in the mass are growing weaker. The general impact of the machine on all industrial populations is to lower the stamina of the individual and make it less likely that he

Page 4

will develop his legs by walking and harden his back and shoulder muscles by manual toil. Until recently the most sturdy and reliable Soldiers were drawn from the agricultural population. Now the drafts are filled with men from towns and cities, more than half of whom have never taken regular exercise or participated in any group game.

Likewise, the machine has tremendously increased the over-all weight of war. Two hundred years ago an army could go through a campaign with what it carried in its train and on the backs of its Soldiers. But in the European Theater in the last war, every Soldier had to have back of him some ten tons of materiel. And the field army that had to rely on its organic transport during an extended advance found itself soon beached high and dry.

So much for change in one direction. The machine has made warfare more ponderous but has also given it greater velocity. In the other direction there has been no change at all. For it is conspicuous that what the machine has failed to do right up to the present moment is decrease by a single pound the weight the individual has to carry in war. He is still as heavily burdened as the Soldier of 1000 years B.C. This load is the greatest of all drags upon mobility in combat and I submit that it is not due to unalterable circumstance. It comes mainly of the failure of armies and those who control their doctrine to look into the problem. [EDITOR: Militaries are populated by weak egomaniacs who don't want to be reminded that they are NOT supermen].

A decisive decrease in that load is possible, once we recognize that our use of the machine can be accommodated to this end. Failing that, we will not in the future make the best use of our human material.

Nothing benefits an army, or any part of it, which is not for the good of the individual at the hour he enters battle. For that reason, the whole logistical frame of the Army of the United States should develop around an

Page 5

applied study of the logistical capability of one average American Soldier. That means getting a more accurate measure of his physical and moral limitations, and of the subtle connection between these two sides of his being. It means rejecting the old dogmatic notion that by military training alone we can transform the American Soldier into a cross between Superman and Buck Rogers. It means that by first enlightening ourselves, we have the main chance to bring forth the Soldier more enlightened.

THE DEAD HAND

GEN. J.F.C. FULLER once said that adherence to dogma has destroyed more armies and lost more battles and lives than anything else in war. I believe this can be proved to the hilt, and that it is time to shake it.

For in the future, we will not be able to afford any unnecessary expenditure. In the study called Men Against Fire, I dealt somewhat narrowly with the problem of conserving the average man's power on the battlefield. The main theme was that the reason all movements in minor tactics tend to fall apart is that we have not rooted our tactical thinking in a sound appreciation of how the average American thinks and reacts when hostile fire comes at him.

But the case as presented there was too limited. It considered man only as a being who can think-who gathers moral strength from his close comrades-who needs every possible encouragement from them if he is to make clear decisions and take constructive action in the face of enemy fire.

But something should be added. On the field of battle

Page 6

man IS not only a thinking animal, he is a beast of burden.

He is given great weights to carry. But unlike the mule, the jeep, or any other carrier, his chief function in war does not begin until the time he delivers that burden to the appointed ground.

It is this distinction which makes all the difference.

For it means that the logistical limits of this human carrier should not be measured in terms of how much cargo he can haul without permanent injury to bone and muscle, but of what he can endure without critical, and not more than temporary, impairment of his mental and moral powers. If he is to achieve military success and personal survival his superiors must respect not only his intelligence but also the delicate organization of his nervous system. When they do not do so, they violate the basic principle of war, which is conservation of force. And through their mistaken ideas of mobility they achieve only its opposite. Almost 150 years ago, Robert Jackson, then inspector general of hospitals in the British Army, put the matter thus simply: To produce united action of bodily power and sympathy of moral affections is the legitimate object of the tactician." The desired objective could not be stated more clearly today. It is universally recognized that the secret of successful war lies in keeping men in a condition of mental alertness and physical well-being which insures that they can and will move when given a competent order.

Yes indeed! Everybody is ready to give three cheers for mobility. But when it comes to the application of the principle at the most vital point of all-the back of the soldier going into battle-the modern commander is just as liable to be wrong about it as the father of the general staff, General Scharnhorst, when he wrote these incredi-

Page 7

ble words: "The infantryman should carry an axe in case he may have to break down a door." Scharnhorst did not lack for company. You cannot read far into war without noting that among the great leaders of the past there has been a besetting blindness toward this subject. Either they have not deemed it worth mentioning among the vital principles of command, or their thoughts about it were badly confused.

Take Marshal Maurice de Saxe for example since his grasp of moral problems was on the whole profound.

About training he wrote eloquent truths like this one, "All the mystery of combat is in the legs and it is to the legs that we should apply ourselves." But when de Saxe turned his thoughts to the problem of man's powers on the battlefield, he said: "It is needless to fear overloading the infantry Soldier with arms. This will make him more steady."

Making all allowances for the more limited movements during battle and the short killing range of all weapons during the wars of de Saxe's times, it must still be conceded that on this point he sounds like an ass. Overloading has never steadied any man or made him more courageous. And such dictum runs directly counter to the principles of war and the sound leading of Soldiers. But the words are dangerous, if only because de Saxe uttered them. We too often ascribe to successful men a godlike infallibility, instead of weighing all things in the light of reason. What the Great Captains thought, succeeding generations find it difficult to forget and challenge reluctantly despite an ever-broadening human experience.

We are still troubled by commanders who do not "fear overloading the infantry Soldier with arms." Rare indeed is the high commander who will fight consistently and

Page 8

effectively for the opposite. In fact, it is chiefly the high commanders who have laid this curse on the back of the fighting man right down through the ages. The second lieutenants have usually known better.

Take Frederick the Great. He said that a Soldier should always carry three days' food. Take Napoleon. He said on St. Helena that there are five things a Soldier should never be without, "his musket, his cartridge box, his knapsack, his provisions for at least four days and his pioneer hatchet." Take Scharnhorst again... He said that a Soldier should carry with him, besides his arms and a three-day supply of bread, "sixty rounds of ammunition, three spare flints, a priming wire, a sponge, a worm, an instrument for taking the lock to pieces, two shirts, two pairs of stockings, rags to wrap up his feet on a march, combs, brushes, pipe-clay, black balls, needles and thread." We can forget such details as the "worm" and the "sponge." The point is that what a Soldier is required to carry into battle today is more directly related to these hoary prescriptions than to any modern surveyor analysis showing what a Soldier is likely to use most in combat-and what weights he could well be spared by a more foresightful planning for the use of other forms of transport.

In fact, careful research, after first revealing the historic roots of most of these elementary logistical concepts would also enable us to trace their growth right down to the present. But the researcher would look in vain for proof that they are based upon field data rather than upon a blind adherence to tradition. He would perforce conclude with Bacon that: "The logic now in use serves rather to fix and give stability to the errors which have

Page 9

their foundations in common received notions than to help the search for truth!" Perhaps in Frederick's day it was necessary for a Soldier to carry three days' food in his pack. Maybe when Napoleon was on the march there was a sound reason for upping that figure from three to four. One can even give Stonewall Jackson the benefit of the doubt for following Frederick's rule-of-thumb during his campaigns in the Valley. Though observers noted, according to Col. Henderson, that it was the habit of the troops to bolt their three rations as soon as possible and then scrounge around for more.

But why in common sense during World War II did we put infantrymen across defended beaches carrying three full rations in their packs? In other words, nine packages of K rations, weighing roughly the same number of pounds! We did it time and again in landings where "hot cargo" shipments of food were coming onto the beaches right behind the troops and almost tripping on their heels.

One package would always have been enough-one third of a ration. In fact, we learned by actual survey on battlefield that only some three per cent of the men along the combat line touched any food at all in the first day's fighting. And that water consumption was only a fifth what it became on the second day and thereafter.

Such is the economy that can be achieved by virtue of a churning stomach. But compared to this reality, we continued until the end of the war to overload our forces with food every time we staged a major attack. To understand why we did it, we must disregard field data and look into history.

Some centuries ago Frederick had an idea.

Page 10

THE FIRE LOAD

A MORE critical and debatable issue than the amount of rations to be carried is the weight of the fire load, since fire is the mainspring of mobility and men can't shoot with empty guns. Again the historical roots of the solution are worth remarking.

Outdoing Scharnhorst, von Moltke in his time decided that 200 rounds of ammunition was a more fitting load for the sturdy Prussian. That became the standard requirement for modern armies. Both sides used it during the Russo-Japanese War, and most armies likewise used it in World War I. So far as may now be learned, no one of any importance saw fit to question whether that figure of 200 rounds had any justification, either in tactics or logistics. In the American Army in France of 1917-18, our commanders usually adhered to-the practice of requiring troops to carry a full ammunition load during the approach march, even in moving into a "quiet" sector.

And in hot weather the results were brutal. We can write off the general policy with the simple statement that troops usually had to carry ten times as many cartridges as there was any likelihood they would use.

Following World War I, several general staffs, and particularly the French, gave some thought to the proposal that with the improvement of first-line transport through motorization it had become possible to relieve the Soldier of carrying his own ammunition reserve. But these good intentions bore no tangible fruit, though in the course of World War I such weapons and equipments as the grenade, trench knife and gas mask had been added to the Soldier's over-all weight.

When World War II came along, the rule-of-thumb

Page 11

laid down almost a century before by Moltke still gave the infantryman blisters around his belly, though meanwhile, owing to changes in civilian transportation, the system of forward supply had undergone a transformation so revolutionary that it had become almost impossible for the combat line to run out of ammunition. Jeeps and amtracs would run the stuff right up to the company CPs and 0P ring line. And when they couldn't go fast enough, planes were dropping it there in bundles.

Despite this altered situation there was no relief for the human carrier. True enough, we did not follow the Moltke prescription right down to the last cartridge. But we deviated from it, not primarily to lighten the Soldier's load but to make room for other types of ammunition.

For example, during the last two years of operations in the Pacific, the rifleman put across a beach generally carried eighty rounds for his M1 or carbine. This special dispensation was simply granted him that he might the better carry eight hand grenades, or in some cases five.

It was presumed that in the close-in fighting he was likely to meet, five to eight grenades would give him a wider margin of safety than double the amount of his rifle ammunition.

In the event, such calculations were found to have little practical relation to what took place along the line of fire.

When you examined company operations in atoll fighting in detail, it was evident that the Soldier who used grenades at all was almost as rare as the man who fired as many as eighty rounds from his rifle in anyone day of action.

Which is to say that the load of grenades the line was required to carry did not promote either increased safety or greater firepower. Eight grenades are a particularly cumbersome burden. They weigh 10.48 pounds. Had the grenade load of each man been cut by three-quarters

Page 12

(giving him two grenades) it is a reasonable assumption that the over-all and expedient tactical use of that weapon would not have been reduced, and the force so lightened would not have been made more vulnerable.

With all hands carrying eight grenades, the number of men making any use of that weapon at all was consistently less than six per cent of the total in any general action. Research showed further that the grenade was rarely put to any practical use in the initial stage of an amphibious attack. This was also true in Europe.

Having been a grenadier in the Army before I became qualified at anything else, I have a natural sentimental fondness for the grenade. In the First World War, I was convinced that the throw as taught was bad for American practice, and therefore conducted the first experiments that resulted in its change. But at that time I learned that if the weapon is to be employed.... usefully, it must be understood that a definite penalty IS attached to overestimating its usefulness. That still applies. The high command falls into such an error when it overloads the man. The Soldier himself makes the error-as we learned in too many cases-when he uses the grenade to clean out the unseen interiors of such places as underground air raid shelters and thick-walled blockhouses, and then takes it for granted the job is tactically finished.

I agree that there are conditions of terrain, and situations that involve movement through entrenchments or against houses, where the grenade is all but indispensable.

But common sense says also that if it is mobility we want, there is no more justification for loading men with grenades they are not likely to use than to send them forward burdened with so many sticks and stones. In fact, that might be better, for they would then drop off their ballast at the earliest possible moment.

Page 13

This same argument would eliminate altogether any further issuing of the bayonet. That weapon ceased to have any major tactical value at about the time the inaccurate and short-range musket was displaced by the ride. But we have stubbornly clung to it-partly because of tradition which makes it inevitable that all military habits die a slow death, but chiefly because of the superstition that the bayonet makes troops fierce and audacious, and therefore more likely to close with the enemy.

I doubt that any combat officer of the last war below field grade would agree that this idea has any merit whatever. Their observations are to be trusted more than the most positive opinions of any senior commander who has had no recent experience with warfighting.

The bayonet is not a chemical agent the mere possession of it will not make men one whit more intrepid than they are by nature. Nor will any amount of bayonet training have such an effect. All that may be said of such training is that, like the old Butts Manual, its values derive only from the physical exercise. It conditions the mind only in the degree that it hardens the muscles and improves health.

The bayonet needs now to be re-evaluated by our Army solely on what it represents as an instrument for killing and protection. That should be done in accordance with the record, and without the slightest sentiment So considered, the bayonet will be as difficult to justify as the type of slingshot with which David slew Goliath. A situation arose during the siege of Brest in August 1944, when the 29th Infantry Division found that an improvised slingshot was useful in harassing the enemy. And about all that may be said for the bayonet, ,too, is that there is always a chance of its being used to advantage. But the record shows that that chance is extremely slight

In the Pacific fighting of World War II, more men were run through by swords than by bayonets.

In our European fighting there is only one bayonet charge of record. That was the attack by the 3rd Battalion, 502nd Parachute Infantry, at the Pommerague Farm during the advance on Carentan, France, in June 1944. In that attack three of the enemy were actually killed by American bayonets. It is a small irony, however, that these killings took place about six minutes after the main charge had subsided. And it is a somewhat larger irony that the one junior officer who actually closed with the bayonet and thrust his weapon home was subsequently relieved because he was not sufficiently bold in leading his troops.

AIRBORNE EXAMPLE

SINCE we are talking about mobility, and how to control the loading of the Soldier toward that end, there is no chapter from our past more instructive than

Page 15

our airborne operations of World War II.

In the European Theater, the basic individual ammunition load for the Paratrooper was eighty rounds for his carbine or M1 [Garand], and two hand grenades. When the Paratrooper jumped into Normandy on June 6, 1944, he also carried these things: 1 rifle and carrier part, 1 English mine. 6 packages of K-ration, 1 impregnated jump suit, 1 complete uniform, 1 steel helmet and liner, 1 knitted cap, 1 change of underwear, 2 changes of sox, 1 entrenching tool, 1 gas mask, 1 first-aid pack, 1 spoon, 2 gas protective covers, 1 field bag with suspenders, 1 packet of sulfa tablets, 1 escape kit, and a set of toilet articles.

Despite all that weight, the most salient, characteristic in operations by these forces was without "doubt the high mobility of all ranks. That was because" in most of them used common sense. They jumped heavy but they moved light. Once on the ground, most of them ditched every piece of equipment they considered unnecessary. They did this without order, and often before they had engaged any of the enemy or joined up with any of their comrades. It was a reflex to a course of training which had stressed that the main thing was to keep going.

The mainspring to the movement of these forces lay in the spirit of the men. They moved and hit like light infantry, and what they achieved in surprise more than compensated for what they lacked in firepower.

Further, at every point they pressed the fight hard, and the volume of fire over the whole operation proved to be tactically adequate, though supply remained generally adverse.

The 82nd and 101st Divisions jumped into one situation where for two days all their elements were engaged by the enemy and only those groups fighting close to Utah Beach had an assured flow of ammunition. Some

Page 16

of the groups got additional ammunition from bundles dropped either by the initial lift or by resupply missions.

But until the airborne front was passed through by the seaborne forces, many of these riflemen were completely dependent on the ammunition they had jumped into Normandy with-eighty rounds and two grenades.