Militarized, Folding All/Extreme Terrain "Mountain" and Electrical Bikes (F-ATBs, F-MTBs, eMTBs)

COMBAT REPORT: IRAQ

BASRA, IRAQ: A British Soldier on patrol speaks to an Iraqi boy in the southern city of Basra, 500 kms south of Baghdad 06 January 2005. It is mainly British forces that patrol this city.

U.S. ARMY TESTING & OPERATIONAL USE IN AFGHANISTAN/IRAQ

MONTAGUE MILITARY BIKE R & D

www.youtube.com/view_play_list?p=DEBB047C1F3DC03D

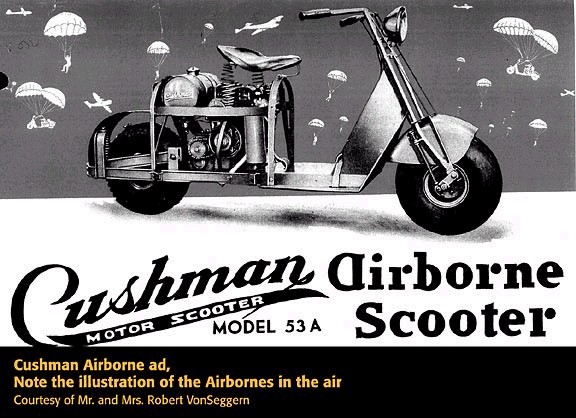

PARATROOPER 2000 on All Terrain Bike (ATB): the future of war is AIRBORNE, not seaborne...

"All men dream: but not equally. Those who dream by night in the dusty recesses of their minds wake in the day to find that it was vanity: but the dreamers of the day are dangerous men, for they may act out their dream with open eyes, to make it possible."

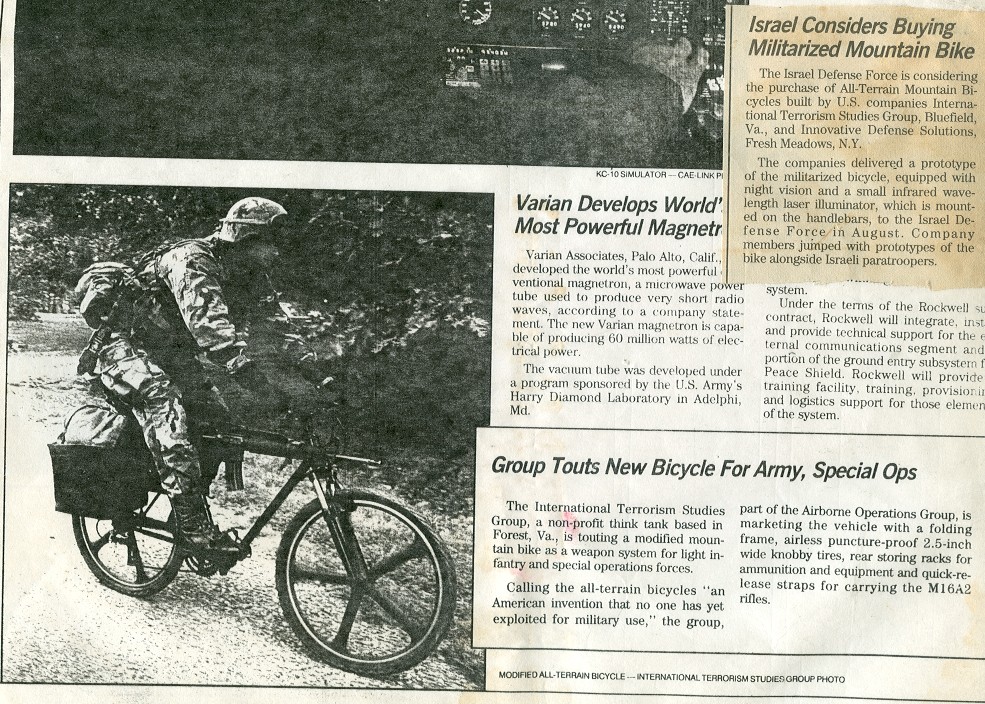

THE AIRBORNE LIGHT BICYCLE INFANTRY (LBI) CONCEPT

The world moves by the speed of the air, not a "slow boat to China". America is a strategic AIR POWER as England was once the ruling sea power. U.S. Airborne forces must be able to rapidly converge on the enemy's most critical center of gravity by AIR power in order to gain strategic and operational surprise; as proven in Grenada, Panama and Haiti. Air POWER is not to be confused with air STRIKES as is vogue in the USAF. Our loss of Pristina airport to the Russian Airborne in a permissive motor march in Kosovo is a perfect example of the weakness of having to wait for marine peacekeepers driving long distances overland (from Greece!!!) to inland areas better reached by air-delivered forces. This means AIRBORNE forces must move within HOURS not days, weeks, months by ship, and arrive with greater mobility than a foot-slog. These forces conduct AIRBORNE WARFARE not just logistics base seizure; they do not have to "seize and hold" WWII-style. The days of piling supplies on the beach for an enemy to cream a bloated marine force are over; the Russians know this, we do not--as we insist on wasting BILLIONS on land-locked, slow-to-deploy, sea-based gyrene units that once ashore foot-slog and truck-hop into enemy land mines.

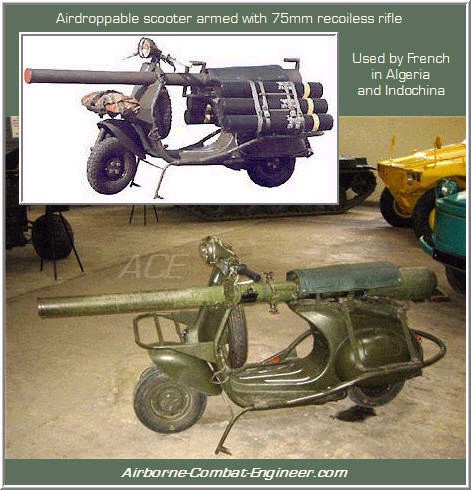

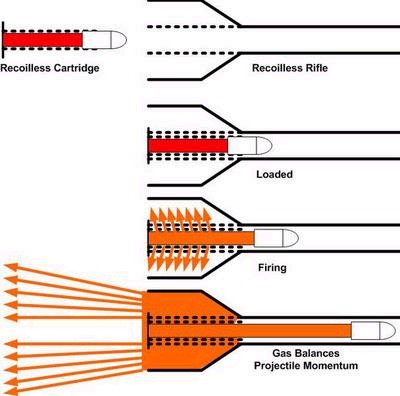

The way to create a fully mobile U.S. Airborne/Air Assault Air-Mech-Strike Force is by creating LTC Richard Liebert's "Dragoon" units: heavily armed mounted Soldiers who use All-Terrain Vehicles like diesel-powered armed Para-Gators now used by the XVIII Airborne Corps and folding bikes and carts backed by light TRACKED Armored Fighting Vehicles. "Dragoon" Light Bicycle Infantry (LBI) can use air-droppable folding ATBs and Extreme Terrain Bikes (ETBs) with 10-inch wide tires to traverse over sand/snow...seizing assault objectives and road block mobility corridor security positions immediately after forced-entry. The maneuver of LBI units would be supported by Dragoons in ATVs firing heavy-caliber machine guns, grenade launchers, rockets and recoilless rifles. Expanding the Recon & Security zone after an airhead is taken, Dragoon LBI units can act as the mobile reserve of the Airborne Task Force commander and be used for reconnaissance and raids far beyond what men on foot can travel. The Airborne's battle space tied in with digital communications means extends beyond enemy artillery and rocket weapons ranges and secures the foothold for offensive operations to collapse the enemy before he can react.

DETAILS:

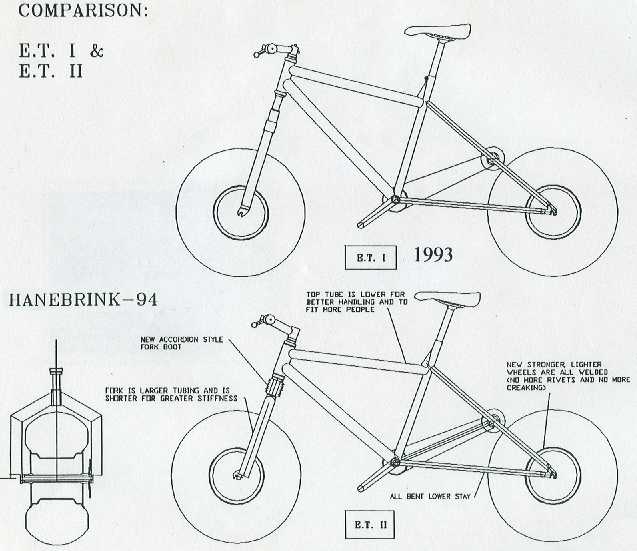

Hanebrink Extreme Terrain Bike (ETB)

Mike Stanley's awesome military Hanebrink ETB

OPERATION: Bike-Jump-Feasible

www.youtube.com/watch?v=Pr3GAOQIkDk

(Images-negatives owned by 1st TSG (A) donated to the U.S. Army; re: Infantry magazine, January-February, 1995)

ITSG Begins Military Bicycle Development in 1988

1992

1991

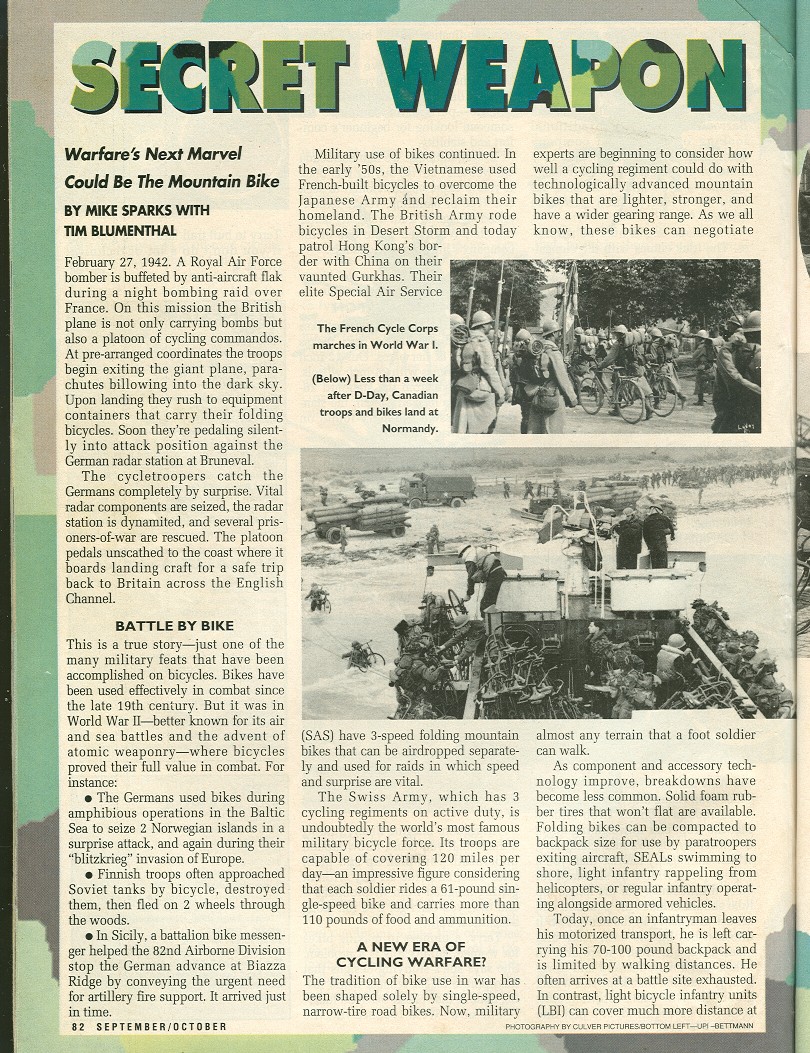

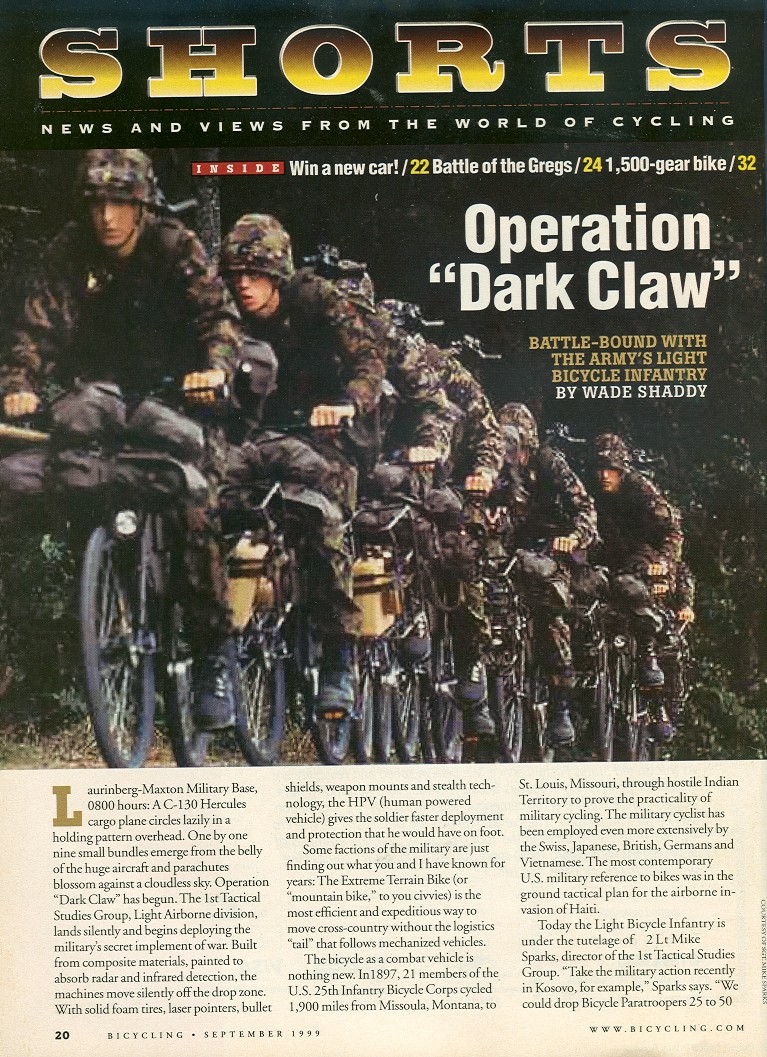

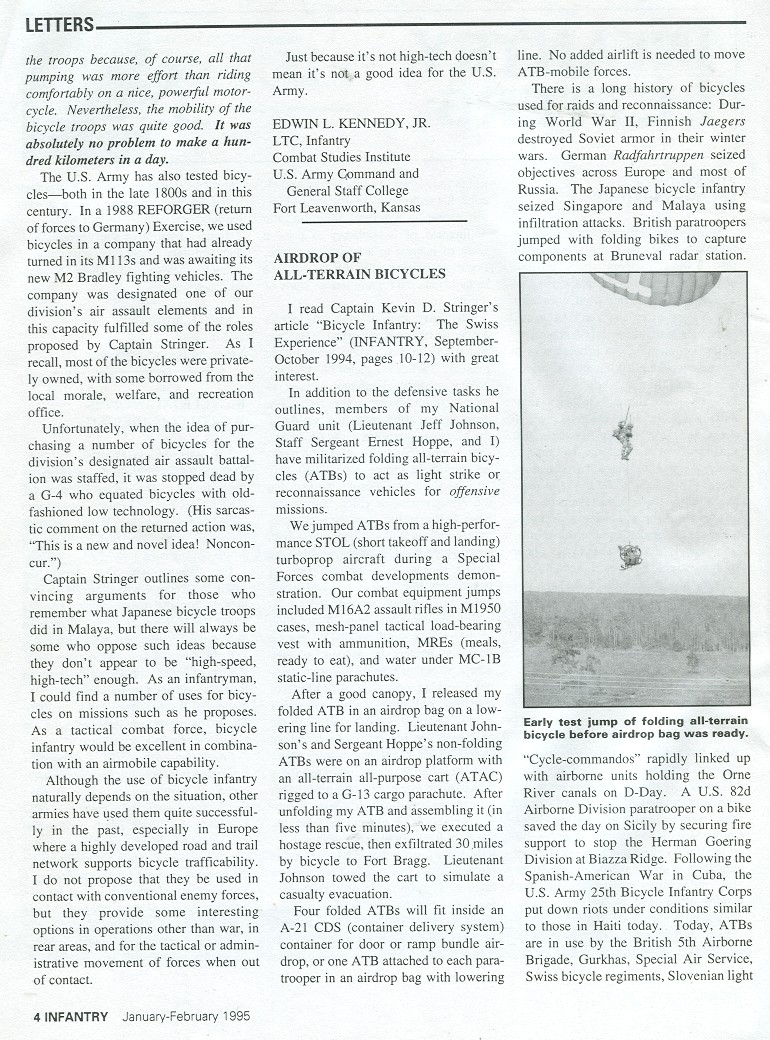

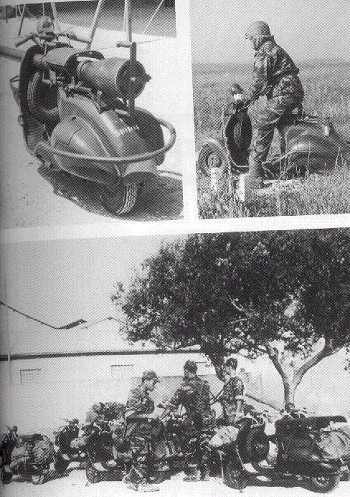

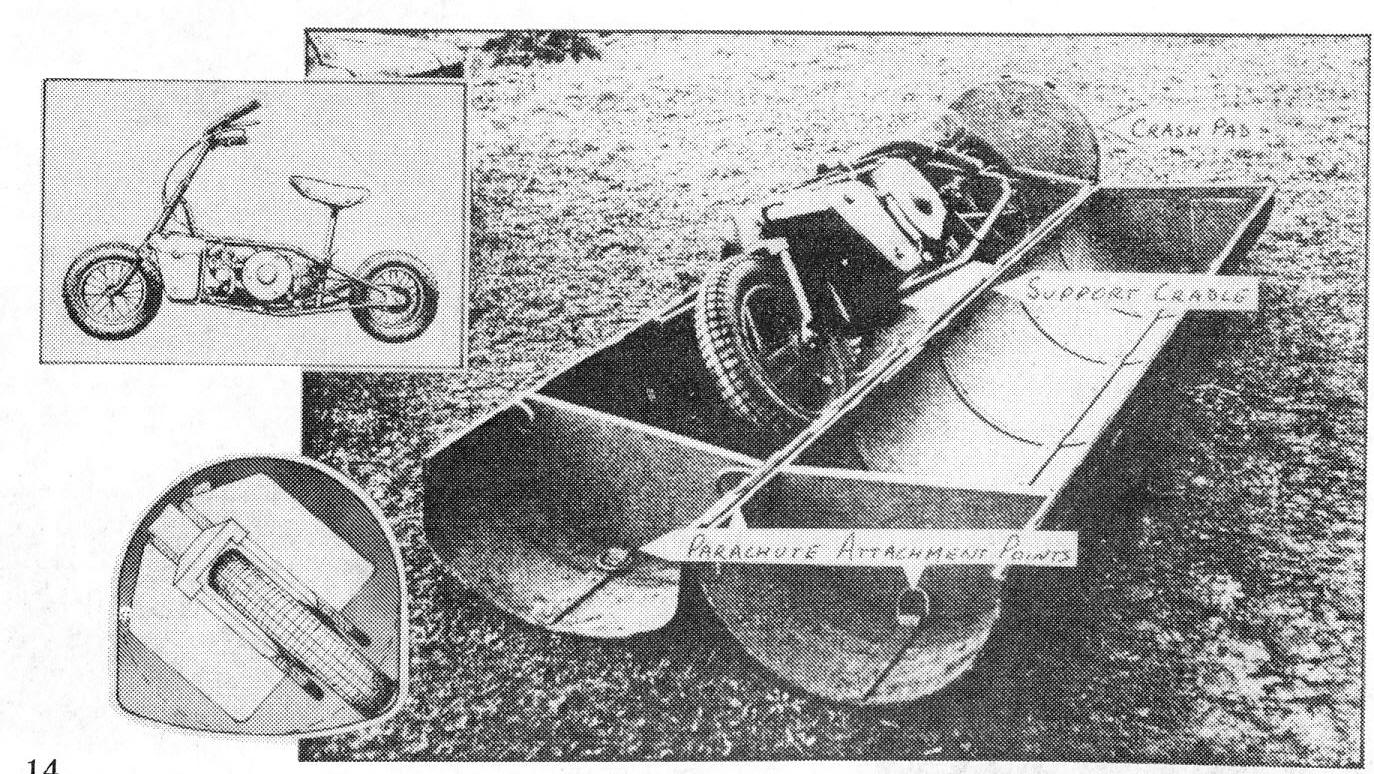

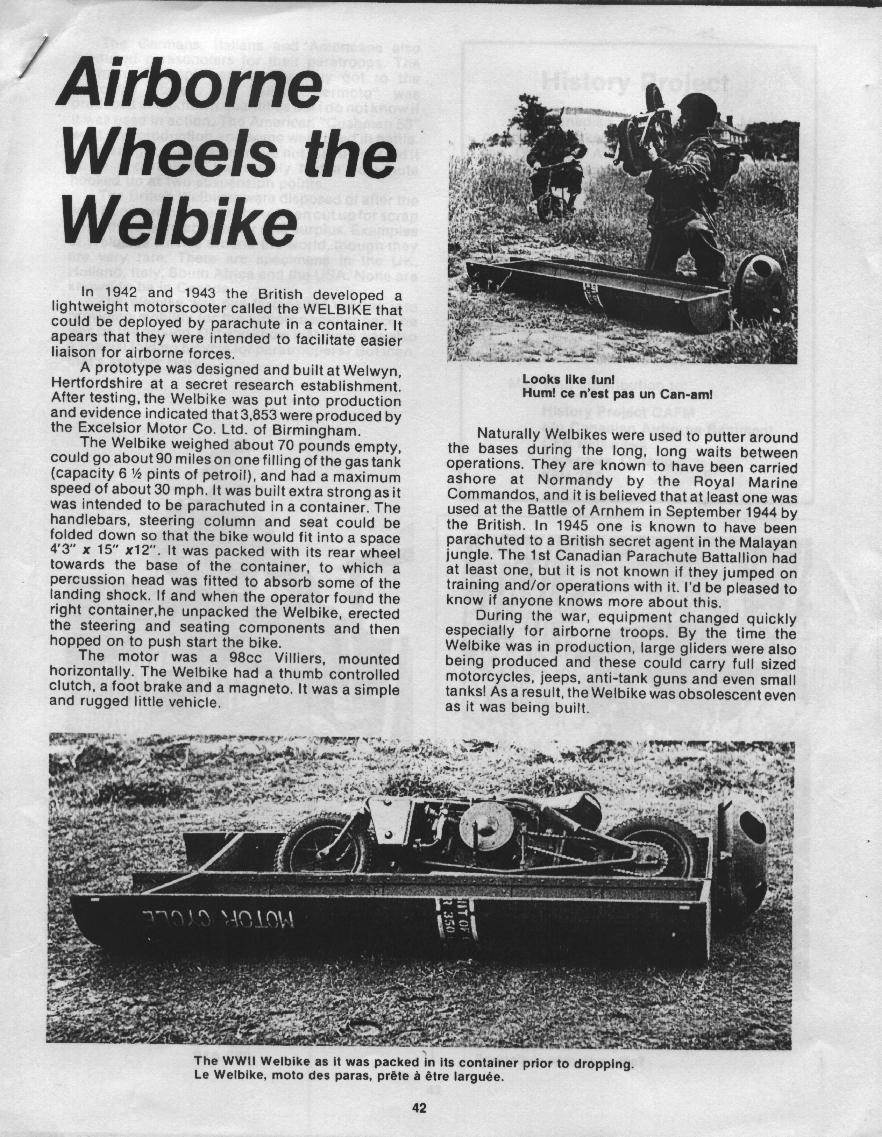

Our early 1992 parachute test of the folding bike was not conclusive due to the exposed condition of the bike for the jump, though we found out later this was successfully done by the British Airborne in WWII combat (see below). However, it proved the ease which parachute delivery can be used to deliver ATBs. Later R&D led to the padded airdrop bag for folded ATBs to be jumped with common Airborne combat equipment attached to ready-for combat individual Paratroopers as lowering line loads as depicted above or Container Delivery System (CDS) bundles to be recovered later (see below) as the 1st Tactical Studies Group (AIRBORNE) Paratroopers did for the OPERATION DARK CLAW demonstration, February 11, 1993 at Laurinberg-Maxton airfield (Home of the U.S. Army Golden Knights) near Fort Bragg, NC. "Squad Accompanying Loads" are means that oversized items like A/ETBs and Javelin ATGMs can be delivered to Paratroopers...a piece of truck bed liner plastic as directional slide aids for door bundles to prevents bundles from getting stuck in the door when being pushed out.

OPERATION DARK CLAW!

Click on thumbnail to view a larger image of picture:

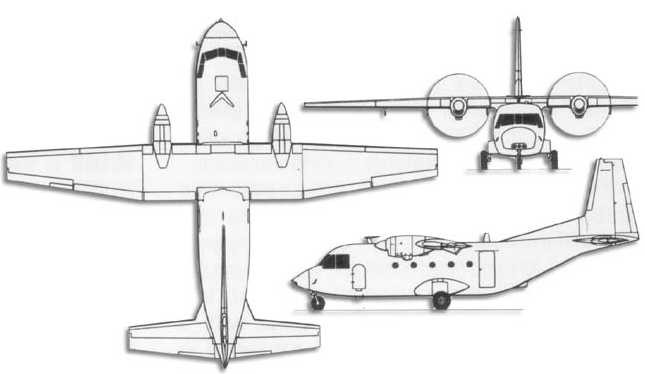

C-212 STOL turbo prop aircraft |

Folded ATB in airdrop bag |

Non-folding ATB and Montague Folding ATB on ATAC as ramp drop bundle |

Dark Claw team members rigged and ready to jump |

Team Leader ready to jump combat equipment and ATB in airdrop bag |

ATB bag rigged under chest reserve |

Folded ATB in bag with quick release straps |

Paratrooper good exit from rear ramp with ATB bag |

ATB in bag still connected to Paratrooper |

ATB lowered on line prior to landing |

Bag opened to recover ATB

|

Unfolding the ATB in under one minute |

Paratrooper cycles at 10 - 25 mph across battlefield

|

|

|

VIDEO: Operation DARK CLAW, Part 1: Insertion

www.youtube.com/watch?v=pkRaE3UEags

From there, they moved as a unit to rescue a mock hostage from an enemy camp, briefed the SF Command Observers, then took the hostage mannequin on ATAC in tow 35+ miles under their own power back to Fort Bragg, NC. All done in under a few hours time. As way of comparison, according to Gerard Devlin's book Paratrooper! in October 1942, the 88th Glider Infantry Regiment foot-marched the same distance to start glider training at Laurinberg field and it took them 2 DAYS to get there from Fort Bragg! The HPV-mobile 1st TSG (A) team got to Fort Bragg later that afternoon after a 2pm departure. What's fascinating is that the 88th GIR was the Army Airborne's Experimental unit and they had bicycles so they could have went much faster!

www.thedropzone.org/units/88thHISTORY.html

History of the 88th Airborne Battalionby James E. Mrazek

The history of the 88th Airborne Battalion, from its activation, to the time it was amalgamated as a regiment with the 326th Glider Infantry Regiment in France during World War II, is covered in an eclectic assortment of conventional official documents.

Not recorded in them, or elsewhere, are its contributions and the impact these contributions have made to airborne warfare operations and doctrine, to military and commercial airlift operations, to military helicopter operations or to the progress of America, especially through the aircraft industry.

At its activation as the 88th Airborne Battalion on 10 October, 1942, it was intended to be an experimental organization that would introduce the air landing aspects of airborne warfare to America's military forces. Such warfare had been applied by the Germans against the Belgians early during World War II with devastating affect. Germany was able to keep information about these operations from leaking out of Germany.

This much the allies were able to glean through intelligence sources - a number of German Soldiers in large gliders had landed on the surface of Belgian's massive Fort Eben Emael on May 20, 1940. They subdued the fort in less than one hour. The loss of the fort created a gap in the Belgian defenses. Because of the shock of this loss, in only a matter of days, Belgium surrendered. This left France's northern flank defensless to the Wermacht's panzers. Soon France fell and the debacle at Dunkerque followed. The 88th battalion was organized as a hybrid tactical and experimental unit. It was lightly manned and equipped and initially was limited to flying in Douglas DC-3's, the only transport airplane immediately available in those early years for carrying its equipment and available to test airborne techniques and doctrine. Motorcycle, bicycles, guns and equipment issued the (airborne) unit were intended to enable it to load in the airplanes, deplane quickly once landed, hit the enemy swiftly and hard and then hold until relieved. The unit was not constituted for sustained combat. This sort of activity divined by a War Department, promised great things for the future of airborne operations, but it did not foresee, nor did it have to cope with the myriad problems in putting such doctrine into reality. It left this to the 88th to translate a concept into workable tactics, techniques, doctrine and procedures.

There was little, if any, experience available with respect to the loading of equipment into airplanes, and the problems such activities entailed. Nor did the 88th get guidance from any source with such knowledge. What was achieved was achieved through dangerous, difficult, practical experience and the ingenuity and ability of the members of the 88th to overcome the problems that developed.

From the beginning there were problems in securing guns, ammunition and equipment so that turbulence while in flight would not cause it to shift or become free. The 88th learned to use ropes to lash the cargo to tie down rings set into the floor of the airplanes. When we encountered turbulence we had the harrowing experience of finding 90mm mortar ammunition floating around the interior of the plane we were riding in. Initially, we could only resecure it or hold it down the as best we could. The 88th sent some men to Wright Patterson air base to present the problem and try to find solutions. One Mr. Baker offered a trucker's knot, the bowline, later dubbed the Baker bowline by his appreciative students. The bowline could not be untied quickly, slowing the unloading of equipment, so enterprising 88ers added the slippery half hitch, well known to boy scouts and truckers.

Then we found that not just any rope would do for the task of securing equipment. Most of it stretched, permitting the equipment to loosen. We opted for 5/8ths-inch Manila hemp, which was very durable and stretched little.

Pilots of the day had little interest in passengers or cargo of any kind. Their attention was directed to flying the glider. The 88th became concerned when pilots were reporting puzzling problems, especially in taking off, and in having to trim the airplanes unduly in flight. What was amiss was that loads were changing the center of gravity of the airplanes, or were heavier than the load for which the aircraft was rated. We had received no cautionary advice from the pilots on how to distribute loads. With little help from the Air Corps, the 88th devised loading plans taking into consideration the center of gravity.

It was customary to equip each military airplane and glider passenger with a parachute. This was OK for airplanes, but when it came to gliders Lieutenant Al Leonard, one of the primary contributors to airborne techniques, considered the expendability doctrine inherent in air transport combat operations and questioned the advisability of issuing parachutes to passengers in gliders. Al reasoned that gliders normally were towed at about 300-500 feet altitude, too low to use parachutes if the occasion demanded. Moreover, weight was always a problem. If chutes could be dispensed with, equivalent weight in weapons and ammunition could be substituted. Al's argument carried the day, and glidermen ceased to wear parachutes, a condition that convinced paratroopers they never wanted to go into combat in a glider. The air force later adopted the practice of not issuing parachutes to passengers in transport aircraft. [EDITOR: WRONG: not true. Only of late has the USAF wimped out and stopped using common sense.]

To facilitate unit training for the vital task of loading men and equipment into gliders, the 88th built the first full-scale glider mockup. It became the prototype for large formations of mockups in training areas that were used for loading and lashing training of the 88th and all airborne divisions. As with the mockup, so it was with many other items of equipment and training. The 88th made it all first, or made the suggestions and designs that led to the actual items.

These ideas led to modifications of gliders and airplanes, and even to the design of new aircraft. A case in point is the successor of the CG-4A glider, the CG-15. The CG-4A was an innovation amongst aircraft, and was the first of its kind in America. It had little testing, and no combat experience up to that time, and thus fell to Al Leonard and other members of the 88th to suggest improvements that would have be desirable and necessary. These were passed up to the Airborne Command, then in charge of collecting and acting on such information, and they all found their way into the modified CG-4A, the CG-15.

Shortly after take off, early production CG-4As dropped their wheels, and landed on skids that ran part of the length of the fuselage. For the gliders to take off again, crews had a real chore to raise the glider and reinstall the wheels. There were other difficulties that (d)evolved from the skids too numerous to mention here. Al Leonard cited them and suggested that landings be made on wheels. The Air Corps adopted his suggestion. Problems evaporated. Gliders suffered less landing damage, and changed from being expendable to recoverable.

It should be understood that these gliders were largely designed by the Air Corps, with little knowledge of airborne unit requirements. This is where the 88th played an important role. Elements of the 88th tested the air transport capabilities of the XCG-13, the CG-15A, and the CG-19 as well as other glider and transport airplane prototypes and heavily influenced which modifications were made.

The 88th trained the glider infantry regiments, artillery, medical and other battalions and many of the parachute elements of the 82nd, 101st, 11th, 17th divisions in air transport operations. After the 88th was absorbed by the 326th Glider Infantry Regiment in the 13th Airborne Division, members of the former 88th that were then in the 326th also were selected to train the 84th Infantry division for air transportably. From the 88th evolved the information that was to become the basis of airborne operations, training and doctrine manuals.

The aircraft industry incorporated many of the experiences gained in the 88th into the design of airplanes, especially those that were intended primarily as cargo carriers. Perhaps the best example in this trend was the 66 passenger XCG-20, America's largest glider. It incorporated the best of the technology that the 88th had devised and contributed to cargo airplane and glider construction. It was to become the C-123, which gradually evolved into a jet airplane from which the design of many of America's most advanced airplanes have borrowed many design features.

James E. Mrazek

Colonel, USA (Ret.)Colonel Mrazek commanded a battalion in the 326th Glider Infantry Regiment in the 13th during World War II and towards the end of the war commanded the regiment for several months. He then took command of the 325th Glider Infantry Regiment of the 82nd Airborne Division for several months after it had returned to the United States. PKO

WW2 Mystery: U.S. Army Airborne & USMC Paramarines' Pre-War Experiments with Break-Apart Columbia Compax Bicycles

The question is DID U.S. Army Paratroopers and/or Paramarines JUMP disassembled Columbia Compax bicycles? If so, HOW? We know the British jumped BSA folding bicycles uncovered in their hands which is very dangerous as its a snag risk to your parachute deployment. So far, all we have are these blow-ups from a poster hanging in a museum where a Columbia Compax is displayed. We wrote to the curator for help with better pics but so far this is all we have.

As if we need yet more proof that ad hocery results in good ideas that could gain us a tactical advantage falling by the wayside; consider the U.S. military's failure to exploit bicycles for military mobility advantages in WW2--and thereafter....

The U.S. Army lead the world in military bicycle use but then got fat and lazy and disastrously road-bound with motorized trucks and forgot how to use them when it really counted in war.

While the Germans were moving around entire rifle battalions by bicycle to achieve decisive effects like repelling the British at Arnhem, at best we used bicycles tactically en masse only if they were captured. The point of this is that military bikes must be ORGANIC to U.S. military units so they are used aggressively in war practice so when the fear of life/death settles in during a war their utility and usefulness to FAN OUT INFANTRY QUICKLY to get decisive kill/capture positions or to control ground to deny the enemy its use (prevent land mines from being laid) will be established and not be ignored.

www.usmilitariaforum.com/forums/index.php?showtopic=2016

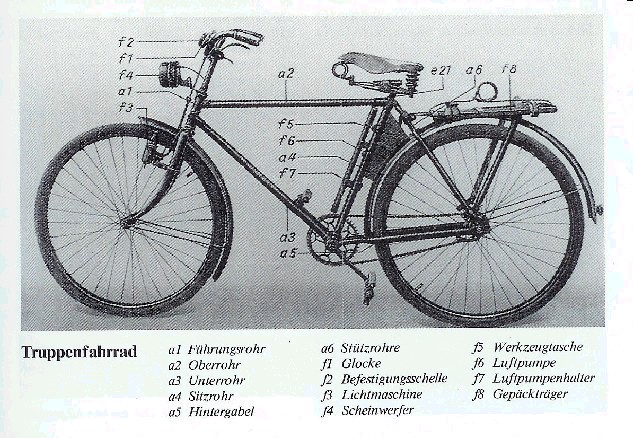

Johan Willaert from Belgium writes:Although the U.S. Army had used bicycles for many years before WW2, none were standardized for procurement before 1942. The Army's official use for these bicycles was: "To provide Transportation for Personnel engaged in Dispatch or Messenger Service". Of course they were used for many other purposes. They proved a fast and economical way to get around Depots, Camps and Airfields.

The "Bicycle, Military, Universal" was adopted in October 1942 by the Ordnance Department. It was a military version of the Westfield "Columbia" and was equipped with heavy duty rims and spokes. It came with a D-Cell powered headlight on the front fender and basic tools were carried in a toolbag attached to the Persons saddle. A tire pump was clamped to the frame.

These bikes were manufactured by both Westfield Columbia and Huffman with only minor differences in parts. Huffman fenders were rounded as opposed to gothic ones on the Columbia, chain guards varied and Huffman front sprockets had a unique whirlwind design.... All parts were interchangeable. Early rubber pedal blocks were replaced with wooden ones later in the war. Early frames had a curved front tube but these were replaced with straight tubes on later models. Late in WW2 Columbia produced a Women's model. Folding "Compax" models were tested by [U.S. Army] Airborne Troops and the U.S. Marine Corps but saw no action in Europe in WW2.

www.theliberator.be/BicyclesImages/MG138969Nieuwpoort.jpg

Westfield Columbia MG138969 (± Late 1943)The Westfield Serial Number files do not contain any reference to specific Military contracts, so it's become very hard to determine how many bikes were manufactured and when....

Huffman frames were dated, but there too there's no reference to how many were made...

I am trying to put together a database with Models and Serial Numbers and their location, so I invite you to post that info here with a picture of the bike if possible....

For more info and wartime images, feel free to visit the Bicycles pages of my site: www.theliberator.be

Thanks,

Johan

Willaert's U.S. Military WW2 Bicycle Research Page

www.theliberator.be/militarybicycles.htm

Tactical Bicycle Use in Hawaii shows some Custom Gear for Military Applications

U.S. Army Signal Corps Photo via Jerry Cleveland

Members of the Intelligence Platoon, HQ Company, 34th Infantry Regiment on patrol in Hawaii. Rifles are carried in leather scabbards on the front forks. Note the Willys MA Jeep in the background...

Another WW2 Bicycle Mystery: By Parachute or Glider?

One of the few surviving Columbia's in Europe is displayed in the Airborne Museum of Sainte-Mère-Eglise, Normandy, France where it sits under the wings of a C-47 aircraft. MG145375 was left behind during WW2 and ended up with a local farmer who used it well into the 1970's before donating it to the local museum where it underwent complete restoration...

WATCH THE CLASSIC MOVIE, "The Longest Day" based on Cornelius Ryan's Book

WATCH THE CLASSIC MOVIE, "The Longest Day" based on Cornelius Ryan's Book

Click on the picture to view the 2-hour movie

Movie details: www.imdb.com/rg/video/browser/title/tt0056197

PROOF! U.S. Airborne Glider-Airlanding Bicycle Use in Combat in WW2

Although many have claimed to see a Compax "Paratrooper" bicycle in the back of the Jeep on the right, the springer type front forks clearly indicate it is not a Columbia Compax.

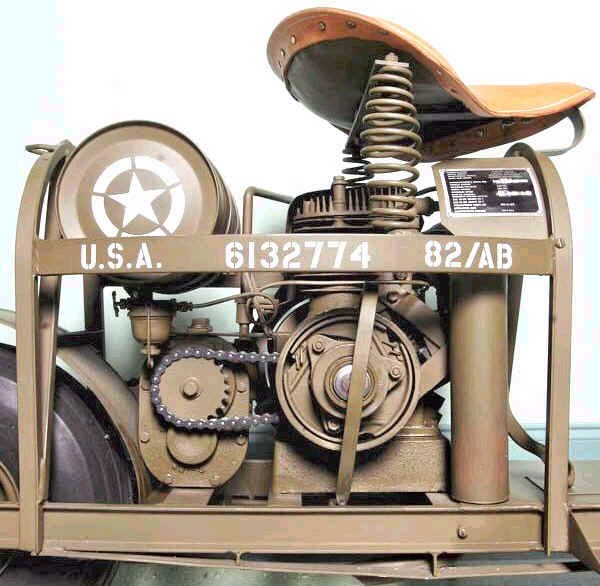

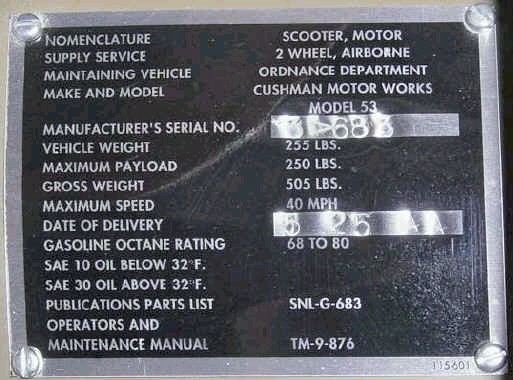

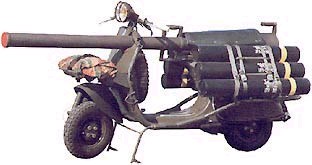

It actually is a Simplex Servicycle. There seems to be another Servicycle in the Jeep on the left where the passenger seat has been tilted forward to make room for the cycle's rear wheel. All vehicles belong to Service Company, 504th Parachute Infantry Regiment of the 82nd Airborne Division and are being loaded into WACO Gliders for the Operation Market-Garden Airborne insertion into Holland in September 1944. During WW2, Servicycles were used by Medical units of Airborne Divisions. Compare the front forks of the Servicycle above to the one shown below.

Father Sampson, Chaplain of the 501st Parachute Infantry is shown on a Simplex Servicycle during Operation Market Garden in September 1944.

Tricycle Resupply in Combat

Al Krochka Photo from Mark Bando's The 101st AIRBORNE-From Holland to Hitler's Eagle's Nest

This image shows Technical Sergeant 5 Mendoza from "B" Company 326th Airborne Engineer Battalion, 101st Airborne Division using a captured/borrowed Dutch Tricycle to transport equipment to a Supply Dump in Veghel, Holland during Operation Market Garden in September 1944. The tricycle is loaded with two A4 Supply Bundles. Note the Parachute First Aid Packet tied to his M1 steel pot helmet.

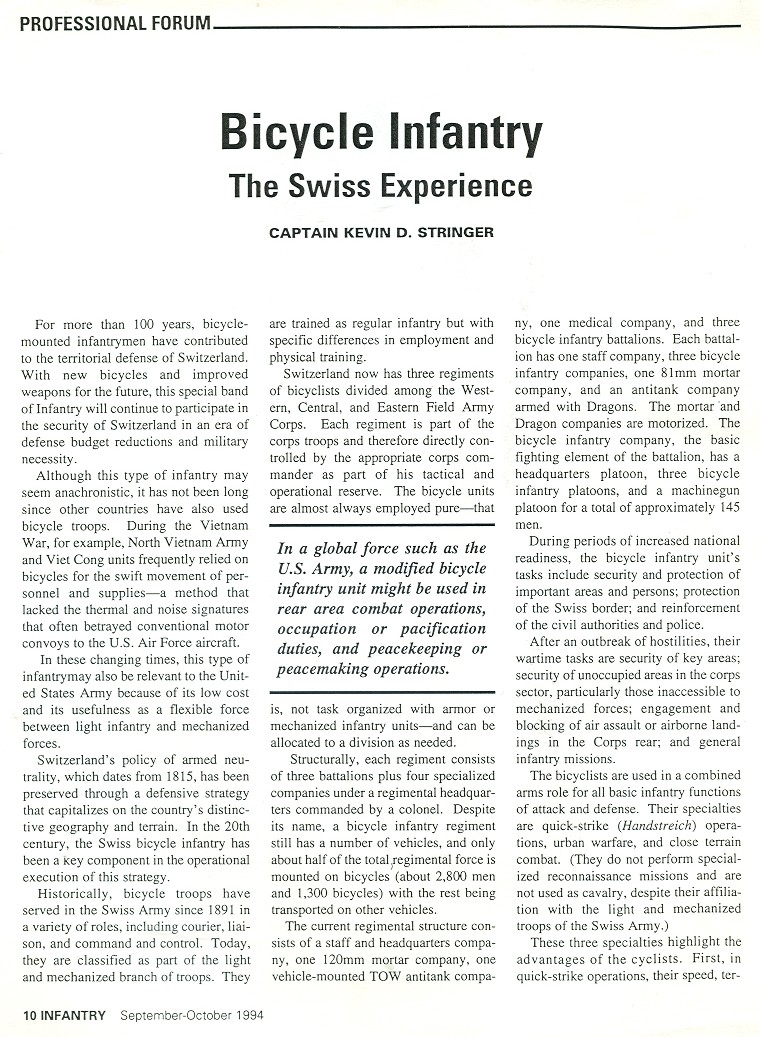

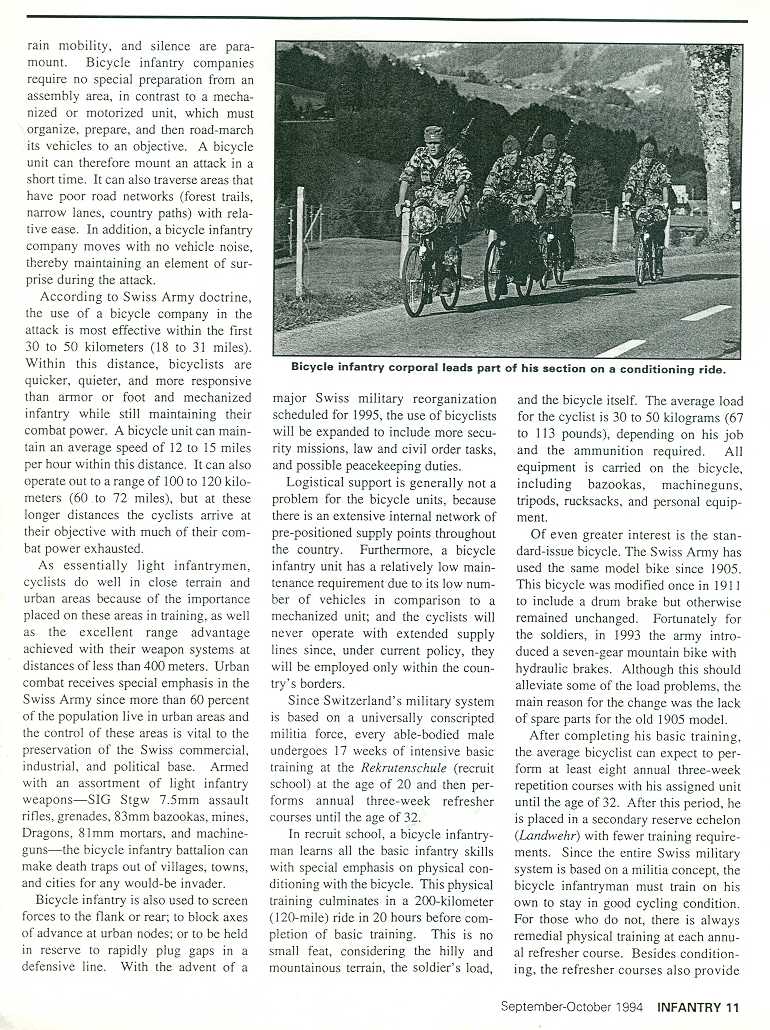

"Bicycle Infantry: the Swiss Experience" by Captain Kevin D. Stringer, U.S. Army Infantry magazine, September-October, 1994

NOTE: narrow-minded Stringer didn't realize that bikes can FOLD and be ATTACHED to armored personnel carriers for armored, mechanized maneuver to the area of operations where LBI would fan out for effect

DETAILS: On-Going 1st TSG (A) Military Vehicle Experiments

Infantry magazine, November-December, 1994

Infantry magazine, January-February, 1995

CDS

CopterBox, HeliBox, MaxiBox

www.defence.gov.au/budget/05-06/dar/volume_01/chapter_01/01b_year_in_view.html

An Air Force Loadmaster and three Australian Army Riggers deploy a helibox and a maxibox load from a C-130J Hercules as part of Exercise Pacific Airlift Rally in Thailand.

Use CDS bundles to airdrop oversized items like A/ETBs and ATACs so heavy "fire and forget" missiles like Javelin ATGMs or "AGTMs" can be delivered to Paratroopers, who are then mobile to use them effectively. So the options are:

1. Jump the folded ATB in airdrop bag attached to the Paratrooper;

a. Rear ramp C-130s/C-27Js/CH-47s/CH-53s

b. Side jump doors of C-130s/C-27Js/C-17s

Obviously, jumping the ATB folded/attached to the Paratrooper will require a major "gut check" of those involved, but the pay-off of 10-25 mph mobility on the ground afterwards is definitely worth it.

The rear ramp jump provides undisturbed air for a majority of the parachute opening sequence; so this using this exit technique should not be a major mental obstacle to overcome. SOF routinely jumps TacSATs and loads almost as large routinely over the rear ramp of C-130 type aircraft today. U.S. Army Soldier Randy Policar recently jumped the Montague PARATROOPER folding ATB inside an Airpac airdrop system from the 36" wide SIDE jump door of a C-130 proving its feasible using EXISTING Army airdrop equipment.

FM 3-21-220 Static Line Parachuting Techniques and Training

Chapter 12 Air Pac Rigging Techniques

http://commutebybike.com/2006/10/23/jumping-with-the-paratrooper

Jumping With The Paratrooper

October 23rd, 2006 by Randy Policar

Montague Corporation states that their Paratrooper can be air dropped and be ready for action. As a Paratrooper myself, I was more than happy to put it to the test.

A few days ago, my Unit conducted an Airborne Operation. It was the perfect opportunity to jump the Paratrooper. But before the jump was to take place I had to rig up the Paratrooper in order for it to be dropped.

I used an Air Pack to rig up the Paratrooper. It was one of the few containers that I had available to fit the whole bike. Here you could see the front tire being placed inside the bag. A lot of padding was used to protect the bike.

The rest of the bike had to be placed inside a HALO kit bag. This was done so that none of the bike would be exposed decreasing the chance of snagging any part of the aircraft upon exit. The handle bars and pedals were removed in order to keep a uniform shape of the Drop Bag. Montague offers folding pedals as an accessory that could be used to keep from having to remove the pedals.

Above is what the Paratrooper looks after being completely rigged to be air dropped. Every part of the Mountain Bike is included so that it could be used on the drop zone.

This was taken on the way to the C-130 Hercules just before station time.

Inside the C-130 just before the jump. Being in a unique Unit, a grand total of five static line jumpers owned the entire aircraft that day. For those of you who jump and are usually packed inside the bird like a can of sardines, stop drooling. Don't worry; I've had my fair share of those jumps as well.

This was taken on the drop zone after a spectacular jump. My landing could use some improvement. But the way I figure is, any jump you could walk away from is a great jump. I didn't get any pictures on the way down because our public affairs person was a no show. I plan on jumping the Paratrooper once again. Next time I'll just leave my camera on the ground for someone to take pictures from the ground up.

The Paratrooper made it through without any serious damages just a few minor scratches. Not bad considering the fact that it was just dropped 1,250 ft above ground level.

2. Drop the folded ATB/ATACSs separately as;

a. Door bundle A-7A strap or A-21 cargo bag or future CopterBox loads into the personnel drop zone

b. Rear ramp CDS A-22 or CopterBox loads into the equipment drop zone (Paratroopers must run to, identify their bundles and de-rig)

In OPERATION PROVE BATTLE MOBILITY, a bicycle assault exercise at Fort Bragg, NC videotaped by a NBC correspondent, Alan Covey the 1st TSG (A) team composed of Combat Medical Specialist LT David Tran, Grenadier/Scout SGT Paul Latham and Team Leader LT Mike Sparks moved rapidly from a simulated airdrop in fully ghillie strip camouflaged-ATBs to assault positions through woods where there was no pre-existing trails. Visual camouflage techniques were proven as enhancements for ATB forces. Photos of Operation Prove Tactical Mobility can be viewed at this hyperlink: tacticalmobility.htm

U.S. ARMY GROUND MOBILITY EXPERIMENTS

TACTICS, TECHNIQUES, PROCEDURES...

www.youtube.com/watch?v=HKMgPbq79m4

The first myth that has to be busted is that light infantry has to take a rucksack to the field at all if you implement all the "Combat Light" techniques described in detail in our Airborne Equipment Shop web site. The only thing that needs to be carried in the rucksack is bulk water, food (MREs) and ammunition. If local water is nearby, it can be collected and purified, instead of being carried thus, saving weight. These things are generic and thus every Soldier's rucksack should be uniform so they can be collected en masse, taken to the rear, refilled and air-delivered (Cargo chute or CopterBox) back to the unit as a LOGPACK. All field-living-SERE (Survival, Evasion, Resistance, Escape) equipments need to be and can be on the "Combat Light" Soldier at all times for the normal temperature/weather range from 20 degrees to 90 degrees. Only in extremely cold weather is a rucksack with survival clothing/tentage required, in extreme hot weather (deserts) bulk water. The British SAS call this living from just the "belt kit".

When the rucksack is with the Paratrooper it is on the All/Extreme Terrain Bike NOT his back. Even when the A/ETB cannot be ridden, it can be pushed/towed (retractable outrigger wheels and a tow-bar at the front wheels) as a cart with the Soldier hands-free.

WHAT IS SO GREAT ABOUT FOOT RUCK MARCHES THAT TAKE ALL DAY?

NO!

YES!

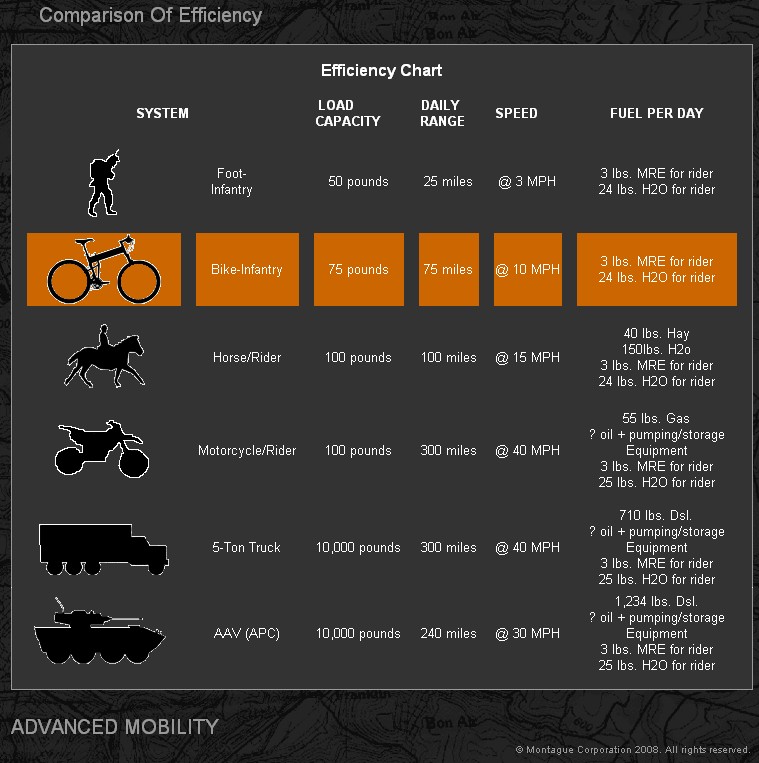

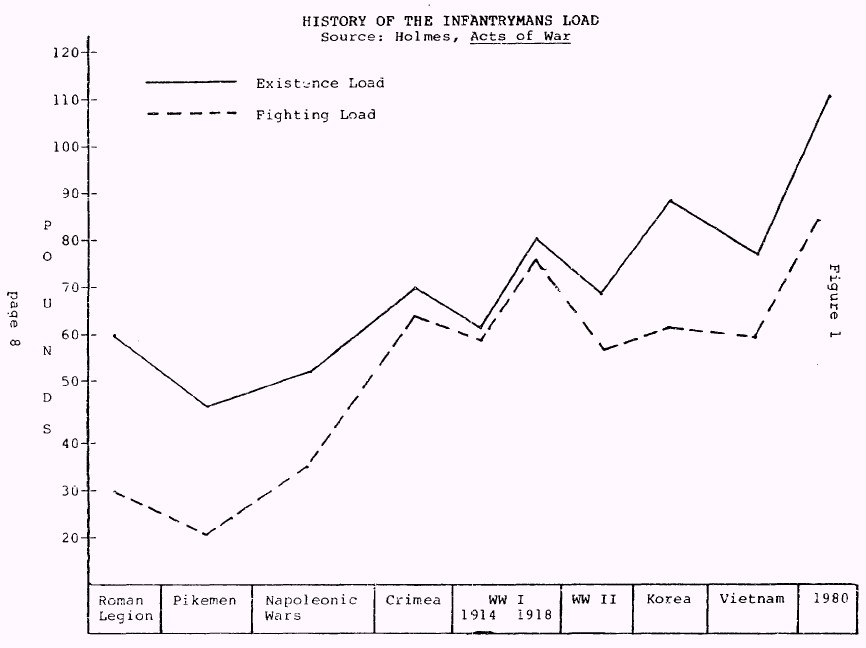

Chart from U.S. Army then Major Stephen Tate's CGSC Master's Thesis "Human Powered Vehicles in Support of Light Infantry Operations"

READ BELOW:

http://stinet.dtic.mil/oai/oai?verb=getRecord&metadataPrefix=html&identifier=ADA211795

Accession Number: ADA211795

Title: Human Powered Vehicles in Support of Light Infantry Operations

Descriptive Note: Master's thesis Aug 1988-Jun 1989

Corporate Author: ARMY COMMAND AND GENERAL STAFF COLL FORT LEAVENWORTH KS

Personal Author(s): Tate, Stephen T.

Handle / proxy Url: http://handle.dtic.mil/100.2/ADA211795 Check NTIS Availability...

Report Date: 02 JUN 1989

Pagination or Media Count: 188

Abstract: This study examines the suitability of using bicycles to enhance the mobility of U.S. light infantry units. Initially the study defines mobility problems encountered by U.S. light infantry units as a result of force design. The study presents historical examples of previous military cycling operations at the turn of the century, during both World Wars, and the Vietnam Conflict. The tactical use, mobility, speed, distance, and load carrying capacity of bicycle troops during each of these periods are discussed. The present use of three bicycle regiments in the Swiss Army is examined. The impact of recent technological improvements in the bicycle industry is examined for possible military application. Keywords: Bicycle; Light infantry; All-terrain bicycle, Mobility; Soldier's load; Vietnam, Swiss army; Strategy; Tactics; Derailleur; World War II; Logistics; Military operations.

Descriptors: *MOBILITY, *LOGISTICS, MILITARY OPERATIONS, MILITARY PERSONNEL, WARFARE, GLOBAL, INDUSTRIES, ARMY PERSONNEL, CAPACITY(QUANTITY), INFANTRY, TERRAIN, CYCLES, MILITARY APPLICATIONS, LIGHTING EQUIPMENT, ARMY, VIETNAM, SWITZERLAND.

Subject Categories: MILITARY OPERATIONS, STRATEGY AND TACTICS

Distribution Statement: APPROVED FOR PUBLIC RELEASE

Get to point B-from-A in a bike in an hour, get off the bikes and into attack position. Walking at a turtle's pace for hours exposes the infantry force to all kinds of air/ground observation, artillery, mortar, small arms fires. Troops tired from long foot marches have lost battles and wars since the Battle of Hastings in 1066 A.D. What is so great about that?

Being able to move through terrain several 1,000 meter grid squares at a time is a form of protection called SPEED. When the LBI force moves it has security front, rear and flank to contact any enemies before they can reach the main body. When contact is expected, LBI teams move by bounding overwatch, one team aimed in on likely enemy ambush points as the other moves ahead--just like armored vehicles do. When it is certain the enemy is ahead, they dismount their A/ETBs and begin fire/maneuver on the enemy. This is more tactical then riding in back of a noisy, unarmed or armored truck.

With a Weapons Gun Shield (WGS) on the end of their shoulder weapons, Paratroopers move forward from cover to cover behind the WGS in the prone, so even if the enemy returns fire, they can survive it to complete the mission----and regain fire superiority with their own weapons. Details of how the "bullet-sponge" paradigm can be defeated is enclosed in the future infantry squad web page link here;

squad.htm The WGS is attached at the front handlebars of the A/ETB during cycling for frontal protection-windscreen in event of enemy contact from the front. It appears that the powers-that-be are starting to listen...

Ref: Prior message on Shields used in MOUT.

Mr. Sparks,

"Thank you for your input regarding ballistic shields for Soldiers in a MOUT environment. You are correct that some sort of shield is needed. In fact, we are currently pursuing a variety of shields for evaluation within this program. Thank you again for your message."

Jonathan Root

MOUT ACTD Force

U.S. Army Soldier Systems Command Hotline

for Food, Clothing, Shelters and Airdrop Systems

DSN 256-5341

Comm: (508) 233-5341

e-mail: hotline@natick-amed02.army.mil

If terrain is not passable by either cycling or towing, the A/ETB can be folded and carried attached to the rucksack for interface with motorized ground/air/sea vehicle transport. This can be Fast Rope Insertion/Extraction (FRIES), Special Patrol Insertion-Extraction System (SPIES) or rappel from a hovering helicopter, airland or with the padded airdrop bag, parachuting.

U.S. Army ARMOR Magazine: Bikes & Tanks = Effective Cavalry

Singapore Army Bicycle-Snipers!

JANE'S INTERNATIONAL DEFENSE REVIEW

Modern Polish Light Bicycle Infantry

THE HISTORY

PRECEDENTS

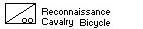

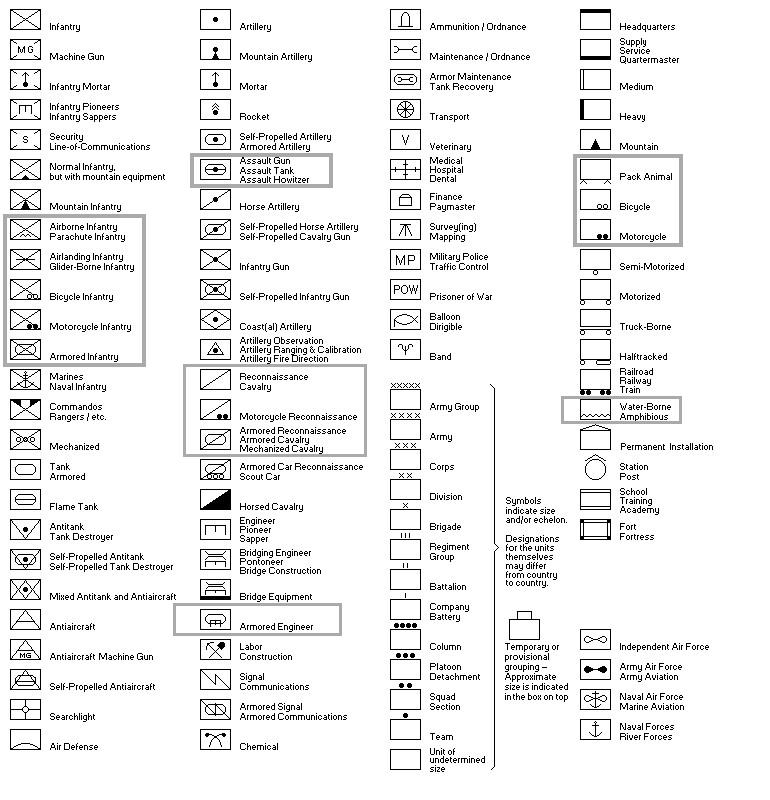

The German Army in WW2 had several light bicycle infantry cavalry companies in every infantry division's reconnaissance battalion. The reason was to have an unit MORE MOBILE THAN THE MAIN BODY THAT WAS WALKING. The German infantry also had light tank assault guns embedded with them to work together just like the M113 Gavins we need today.

The German Army in WW2 had several light bicycle infantry cavalry companies in every infantry division's reconnaissance battalion. The reason was to have an unit MORE MOBILE THAN THE MAIN BODY THAT WAS WALKING. The German infantry also had light tank assault guns embedded with them to work together just like the M113 Gavins we need today.

Dr. Leo Niehorster's excellent organizational web pages document these facts.

http://niehorster.orbat.com/index.htm

http://niehorster.orbat.com/011_germany/41_organ_army/41_id_01-welle.html

| World War II Armed Forces - Orders of Battle and Organizations | Last Updated 01.05.04 |

|

German Army

Organization Infantry Division (1st Wave) Infanteriedivision (1. Welle) 22 June 1941 |

| Diagram of German Infantry Division in WW2 |

|

|

| 1. Welle Infantry Divisions | ||||

| Division

(Commander on 22.06.1941) |

W.K. | Infantry | Other Units |

Comments |

| 1. Infanterie-Division.

Gen.Maj. Kleffel |

I | 1 Regiment

22 Regiment 43 Regiment |

1 | |

| 5. Infanterie-Division.

Gen.Maj. Allmendinger |

V | 14 Regiment

56 Regiment 75 Regiment |

5 | |

| 6. Infanterie-Division.

Gen.Lt. Auleb |

VI | 18 Regiment

37 Regiment 58 Regiment |

6 | |

| 7. Infanterie-Division.

Gen.Lt. Frhr. v. Gablenz |

VII | 19 Regiment

61 Regiment 62 Regiment |

7 | recon battalion: 2 bicycle companies, no heavy company, but 1 lt IG platoon (mot), 1 AT platoon (mot) |

| 8. Infanterie-Division.

Gen.Maj. Höhne |

VIII | 28 Regiment

38 Regiment 84 Regiment |

8 | recon battalion: 2 bicycle companies, no heavy company, but 1 lt IG platoon (mot), 1 AT platoon (mot) |

| 9. Infanterie-Division.

Gen.Maj. Frhr. v. Schleinitz |

IX | 36 Regiment

57 Regiment 116 Regiment |

9 | |

| 11. Infanterie-Division.

Gen.Lt. v. Böckmann |

I | 2 Regiment

23 Regiment 44 Regiment |

11 | |

| 12. Infanterie-Division.

Gen.Maj. v. Seydlitz-Kurzbach |

II | 27 Regiment

48 Regiment 89 Regiment |

12 | |

| 15. Infanterie-Division.

Gen.Lt. Hell |

IX | 81 Regiment

88 Regiment 106 Regiment |

15 | |

| 17. Infanterie-Division.

Gen.Lt. Loch |

XIII | 21 Regiment

55 Regiment 95 Regiment |

17 | recon battalion: 2 bicycle companies, no heavy company, but 1 lt IG platoon (mot), 1 AT platoon (mot) |

| 21. Infanterie-Division.

Gen.Maj. Sponheimer |

I | 3 Regiment

24 Regiment 45 Regiment |

21 | recon battalion: 2 bicycle companies, no heavy company, but 1 lt IG platoon (mot), 1 AT platoon (mot) |

| 22. Infanterie-Division (Luftlande)

Gen.Lt. Graf v. Sponek |

X | 16 Regiment

47 Regiment 65 Regiment |

22 | recon battalion: 2 bicycle companies, no heavy company, but 1 lt IG platoon (mot), 1 AT platoon (mot);

no heavy artillery battalion; all antitank companies had 3x sPzBü + 9x 37mm Pak;

3 supply columns, 6 supply columns (mot), 2 P.O.L. columns (mot); 1 division park.

Airlanding equipment was in depots back in Germany. |

| 23. Infanterie-Division.

Gen.Maj. Hellmich |

III | 9 Regiment

67 Regiment 68 Regiment |

23 | |

| 24. Infanterie-Division.

Gen.Maj. v. Tettau |

IV | 31 Regiment

32 Regiment 102 Regiment |

24 | |

| 26. Infanterie-Division.

Gen.Maj. Weiss |

VI | 39 Regiment

77 Regiment 78 Regiment |

26 | |

| 28. Infanterie-Division.

Gen.Lt. Sinnhuber |

VIII | 7 Regiment

49 Regiment 83 Regiment |

28 | |

| 30. Infanterie-Division.

Gen-Lt-v. Tippelskirch |

X | 6 Regiment

26 Regiment 46 Regiment |

30 | |

| 31. Infanterie-Division.

Gen.Maj. Kalmükoff |

XI | 12 Regiment

17 Regiment Regiment |

31 | |

| 32. Infanterie-Division.

Gen.Maj. Bohnstedt |

II | 4 Regiment

94 Regiment 96 Regiment |

32 | Pionier Bataillon 2 |

| 34. Infanterie-Division.

Gen.Lt. Behlendorff |

XII | 80 Regiment

107 Regiment 253 Regiment |

34 | |

| 35. Infanterie-Division.

Gen.Lt. Fischer v. Weikersthall |

V | 34 Regiment

109 Regiment 111 Regiment |

35 | |

| 44. Infanterie-Division.

Gen.Lt. Siebert |

XVII | 131 Regiment

132 Regiment 134 Regiment |

44 | Art.Rgt. 96; Pzjg.Abt. 46; Pion.Btl. 80; Nachr.Abt. 64.;

recon battalion without armored car platoon. |

| 45. Infanterie-Division.

Gen.Maj. Schliepper |

XVII | 130 Regiment

133 Regiment 135 Regiment |

45 | Art.Rgt. 98; Pion.Btl. 81; Nachr.Abt. 65;

recon battalion without armored car platoon. |

| 46. Infanterie-Division.

Gen.Lt. Ktiebel |

XIII | 42 Regiment

72 Regiment 97 Regiment |

46 | Art.Rgt. 144; Pzjg.Abt. 52; Pion.Btl. 88; Nachr.Abt. 76;

recon battalion without heavy company, but with armored car platoon. |

| 50. Infanterie-Division.

Gen.Lt. Hollidt |

III | 121 Regiment

122 Regiment 123 Regiment |

50 | recon battalion: 2 bicycle companies, no heavy company, but 1 lt IG platoon (mot), 1 AT platoon (mot); the infantry regiment antitank companies had 12x 37mm Pak; the antitank battalion companies had 9x 37mm Pak + 2x 50mm Pak. |

| 72. Infanterie-Division.

Gen.Lt. Mattenklott |

XII | 105 Regiment

124 Regiment 266 Regiment |

72 | Art.Rgt. 172; Radf.Schw. 172; no Field Replacement Battalion; the infantry regiment antitank companies had 12x 37mm Pak; the antitank battalion companies had 9x 37mm Pak + 2x 50mm Pak. |

http://niehorster.orbat.com/011_germany/39_organ_army/kstn_0353.htm

German Radhfahrtruppes (Bicycle-Infantry) converge on Arnhem

| World War II Armed Forces - Orders of Battle and Organizations | Last Updated 31.12.00 |

|

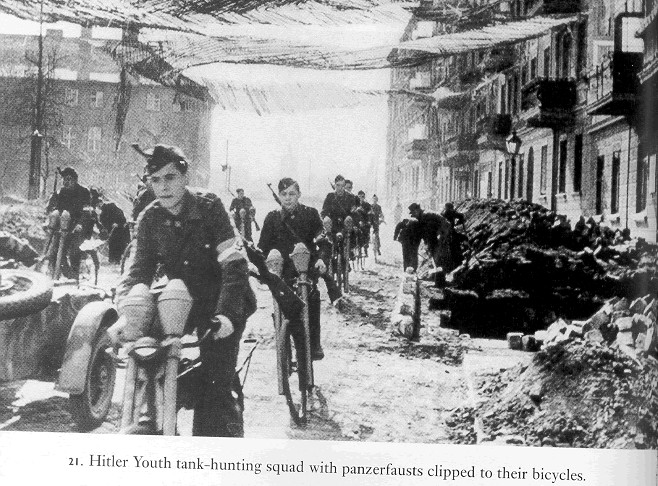

German Army

Organization Cavalry Bicycle Company 1 September 1939 |

|

Radfahrerschwadron

KStN 353 dated 01.09.1939 |

|

| 1 Officer (K) as Company Commander (Pistol) | |

|

Company Headquarters

Headquarters Section 1 NCO as Headquarters Section Leader (Rifle)(on bicycle) 1 Messenger / Bugler (Rifle)(on bicycle) 1 Messenger / Blinker Signaler (Rifle)(on bicycle) 1 Messenger (Rifle)(bicycle) 3 Messengers (Rifles)(on motorcycles) 1 Motor Vehicle Driver (Rifle) 1 car, light, cross-country (Kfz. 1) 3 motorcycles Medic Section 1 Medic NCO (Pistol)(on bicycle) 4 Stretcher Bearers(on bicycles) Combat Trains 1 Senior NCO as First Sergeant / Trains Leader (Pistol) 1 NCO as Armorer (Pistol) 1 NCO for Equipment (Rifle)(on motorcycle) 1 Assistant Armorer (Pistol)(on motorcycle) 1 Assistant Armorer (Pistol) 5 Motor Vehicle Drivers (Rifles) 1 Motorcyclist (Rifle)(on motorcycle with sidecar) 3 Bicycle Mechanics & truck escort (Rifle) 1 Clerk (Rifle) 1 Cook (Rifle) 1 Cook & truck escort (Rifle) 2 motorcycles 1 motorcycle with side car 1 car, medium, cross-country (Kfz. 18) 1 truck, light, open, cross-country for field kitchen 3 trucks, light, open, cross-country for equipment and ammo 9 light machine guns (as equipment reserve) Baggage Trains 1 Enlisted in charge of baggage / clerk (Rifle)(on motorcycle) 1 Tailor (Rifle) 1 Cobbler (Rifle) 1 Driver (Rifle) 1 truck, light, open, for baggage and equipment |

3 Rifle Platoons, each with

1 Officer (Z) as Platoon Leader (Pistol)(on bicycle) Platoon Headquarters 1 Messenger / Bugler (Rifle)(on bicycle) 1 Messenger / Blinker Signaler (Rifle)(on bicycle) 1 Messenger (Rifle)(bicycle) 3 Rifle Squads, each with 1 NCO Squad Leader (Rifle)(on bicycle) 1 Assistant Squad Leader (Rifle)(on bicycle) 1 MG Gunner (Pistol)(on bicycle) 2 Assistant MG Gunners (Pistols)(on bicycles) 7 Riflemen (Rifles)(on bicycles) 1 light machine gun Light Mortar Section 1 NCO as Mortar Section Leader (Rifle)(on motorcycle) 3 Gunners / (Pistols) 6 Assistant Gunners (Rifles) 6 Motorcycle Drivers (Rifles)(on motorcycles with sidecars) 1 motorcycle 6 motorcycles with sidecars 3 light mortars (50mm) |

|

Totals:

4 Officers, 24 NCO, 152 Enlisted; 134 Rifles, 46 Pistols, 18 LMG, 3 Light Mortars; 7 motor vehicles, 7 motorcycles, 7 motorcycles with side cars, 138 bicycles. |

|

From Steve Olderr's superb web site, the "Bicyclopedia" link above, lists an amazing history of the bicycle, military bike history excerpts taken here:

The forerunners of today's A/ETBs have been proven by years of successful military use in war by the Germans, British Commandos, Vietnamese, Swiss and can give AIRBORNE forces 10-25 mph mobility without logistical "tail" that is inherently stealthy. In its 1937 invasion of China, Japan employed some 50,000 bicycle troops. Then the Japanese Army of just 3 divisions defeated the entire British Army in Malaya and Singapore. Their "secret weapon": bicycle jungle infiltration tactics created by a "Studies Group"

"Early in 1941 Colonel Masanobu Tsuji, (scroll down after clicking link) a veteran of the China campaign. was allocated a shoe-string budget and put in charge of a small Southern Military Studies Research Group in Taiwan to investigate problems of jungle warfare. Tsuji was given a report drawn up by two senior Japanese army officers, who had visited Malaya in September 1940. They advised that any attack on Singapore would have to come from the north and reported that the British Air force in Malaya was understrength and its planes obsolete. Tsuji appreciated, as Percival and Dobbie had pointed out, that a frontal attack on Singapore was scarcely feasible but her back door stood open, and he realized that British propaganda was deluding only her own people.BICYCLES AT WAR PHOTO GALLERYTsuji embarked on his task with enthusiasm and verve. The challenge was enormous, for the Japanese Army had no experience of fighting jungle warfare. Soldiers accustomed to cold weather fighting had to be trained to face tropical conditions, and cavalry, which was used in China, had to be abandoned in favour of bicycles. The 25th Japanese Army, which was hurriedly assembled for the invasion of Malaya, was put under the command of Lieutenant-General Tomoyuki Yamashita, probably Japan's most able general. The son of a humble village doctor, Yamashita was then fifty-six years old and was Tojo 's contemporary and rival. He had headed the Japanese military mission to Germany and Italy in 1940 and served in Korea and North China, until November 1941 when he was summoned from Manchuria to command the attack on Singapore.

Yamashita was offered five divisions but decided to employ only three, knowing that this was the maximum force which could be fed and maintained as his supply lines became extended south. The 25th Army comprised the Imperial Guards, the seasoned 18th Division and the highly experienced crack 25th Division, which was one of the best in the Japanese Army.

The Japanese secret weapon was the bicycle and it gave them speed and mobility in the advance down the Malay peninsula

The Japanese swept down the Malay peninsula, carried forward by audacious planning, good fortune and the exhilaration bred by success. The main body of the force were disciplined, hardy and vigorous Soldiers, who had fought together in the China campaign. Yamashita used his mastery of the air and the coastal waters to conduct a dynamic technique of infiltration, enveloping and outflanking which bewildered the defenders and compelled them to withdraw to avoid being cut off from the rear. Confined by the communications system of one trunk road and railway line, the British defence lacked mobility and the Japanese could defeat them in detail. Without tanks and anti-tank guns or prepared lines of defences, the Commonwealth retreat was inevitable, and the Japanese drove relentlessly south. Ironically, when he was almost out of ammunition, Yamashita attacked and General Percival surrendered to his bluff.

Victory brought a thrill of exhilaration to Japan and her allies. The previous year German military leaders had told Yamashita it would probably take five divisions eighteen months to conquer Singapore. In fact, the mission had been accomplished by three divisions in just over two months. For the British, the loss of Singapore was the blackest moment of the Second World War and, in the words of Winston Churchill, 'the worst disaster and largest capitulation in British history'.

--National Museum of Singapore Web Site

VIDEOS: The Fall of Malaya and Singapore The Brits Get Bikes: Defeat the Japs & JerryJap bicyclists take Malaya/Singapore

www.youtube.com/watch?v=Jx38CQkka-Q

The BATTLE

PART 1: Percival had plan to block landing up north but didn't do it, Japs sink air coverless Repulse and Prince of Wales, use bicycle-infantry to infiltrate through British lines, Light tanks prevail because stupid British ASS U ME NO tanks can operate in the jungle; don't fathom LIGHT tanks that are closed-terrain mobile

www.youtube.com/watch?v=9P14DfmapWY

PART 2: non-linear Japs outflank linear Brits repeatedly, IV and pole carry of casualty, planes in crates not helping; if they were folded in BATTLEBOXes they'd be ready to fly, interesting small boat with a cannon on it, Japs encircle Singapore with light tanks and artillery, launch observation balloon to direct fires; British have no planes to knock it down! Cuts off water supply, can't win a fight if forced to dislodge the British so he tries leaflets to get a surrender, Yamashita bluffs Percival to surrender

www.youtube.com/watch?v=8pIpkDk-c04

PART 3: 130, 000 POWs horror made into slave laborers

www.youtube.com/watch?v=lSSJCRToo_Y

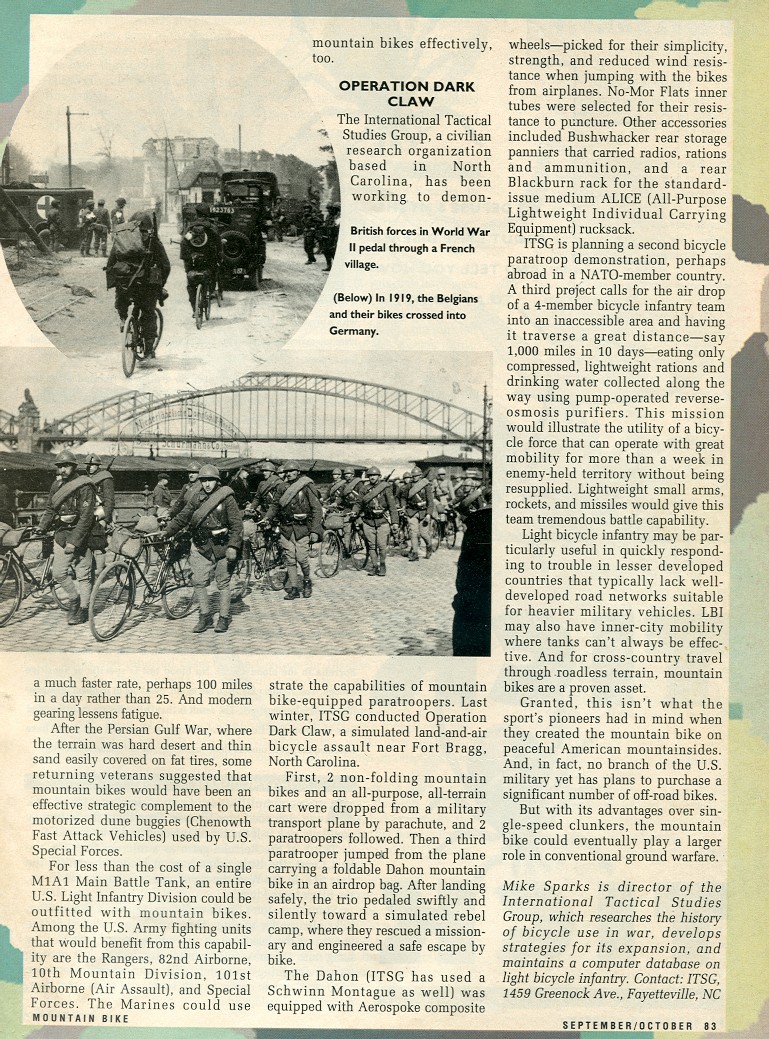

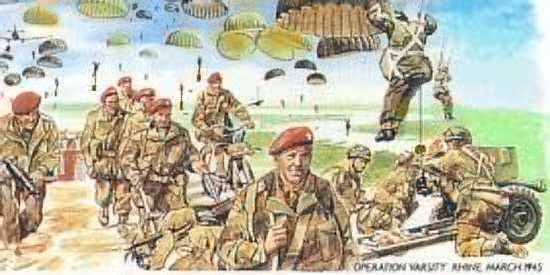

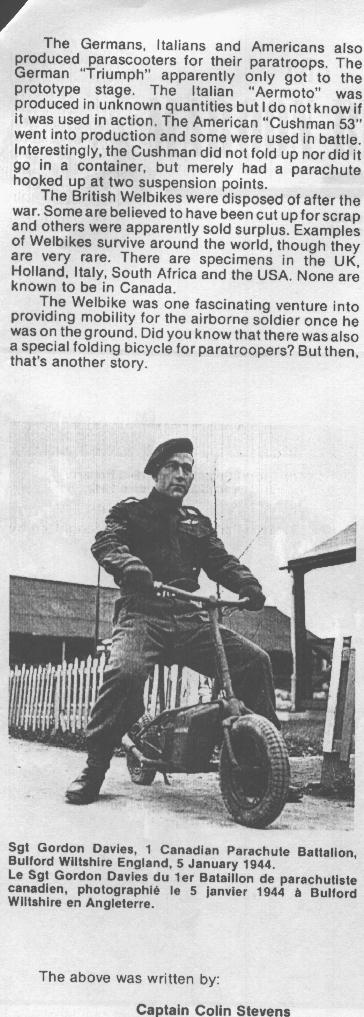

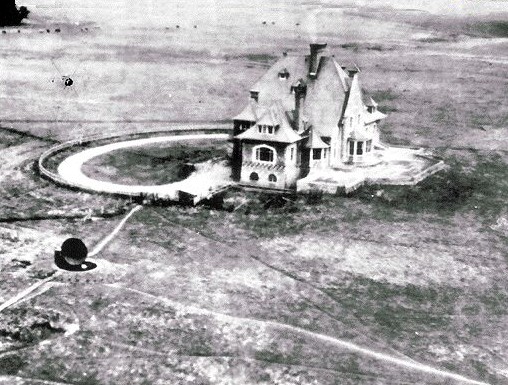

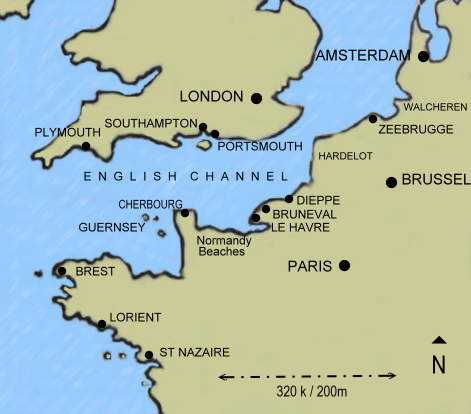

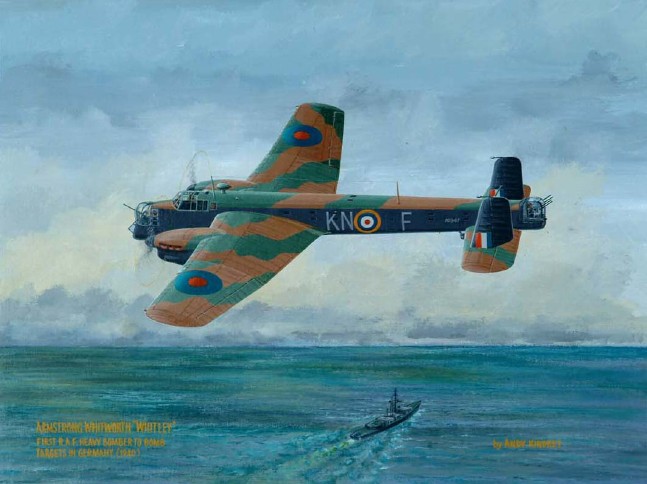

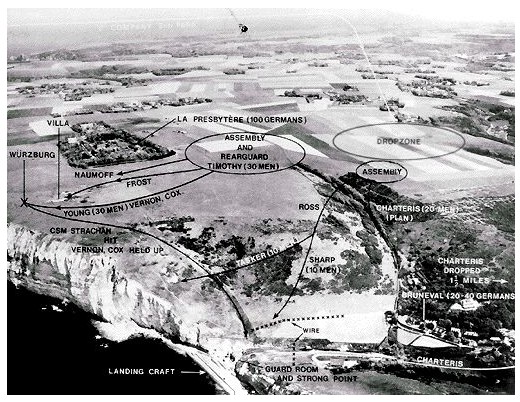

Later in the same year, British Airborne "Cycle Commandos" struck at Bruneval Radar station using folding mountain bikes. Flying in Stirling bombers which also dropped bombs to confuse the Germans, the Cycle-Commandos were paradropped 8 miles away from their objective for secrecy. Using their bikes for ground mobility, the Paratroopers closed on their target silently and captured the necessary radar components and prisoners to bring vital intelligence back to England by sea landing craft.

Details:

www.6th-airborne.org/bike.html

Details & Photos:

Airborne re-enactor equipment page

BSA Airborne Bicycles

BSA Airborne Bike Page

David Gordon's BSA bike pageType G Apparatus - Folding Bicycle

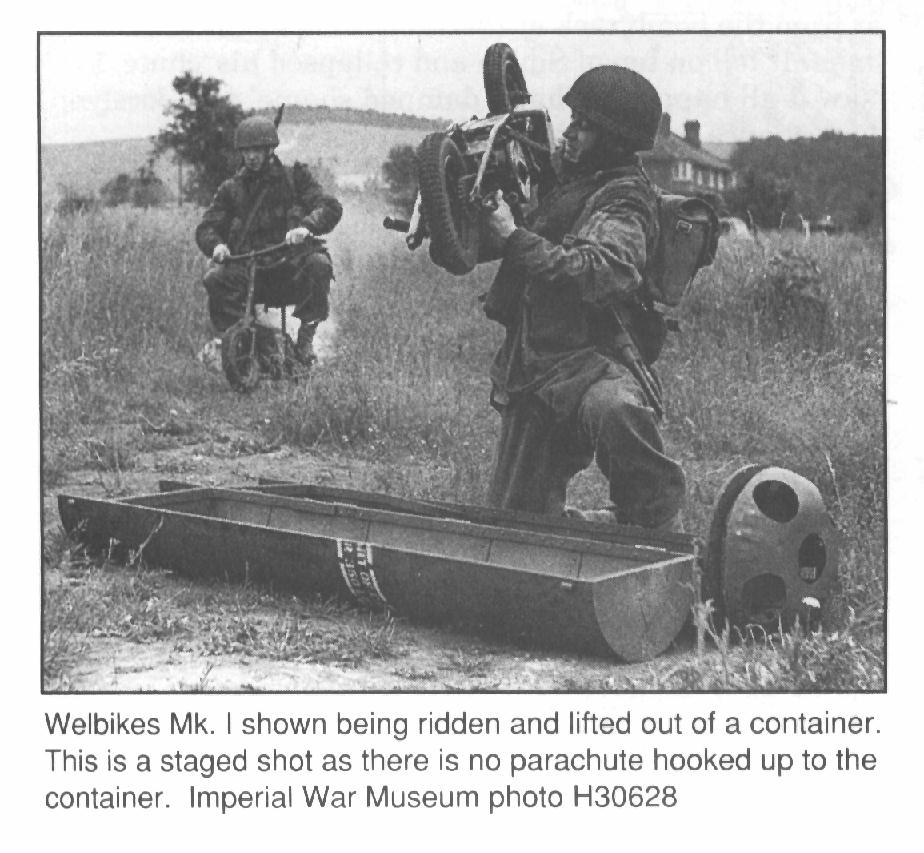

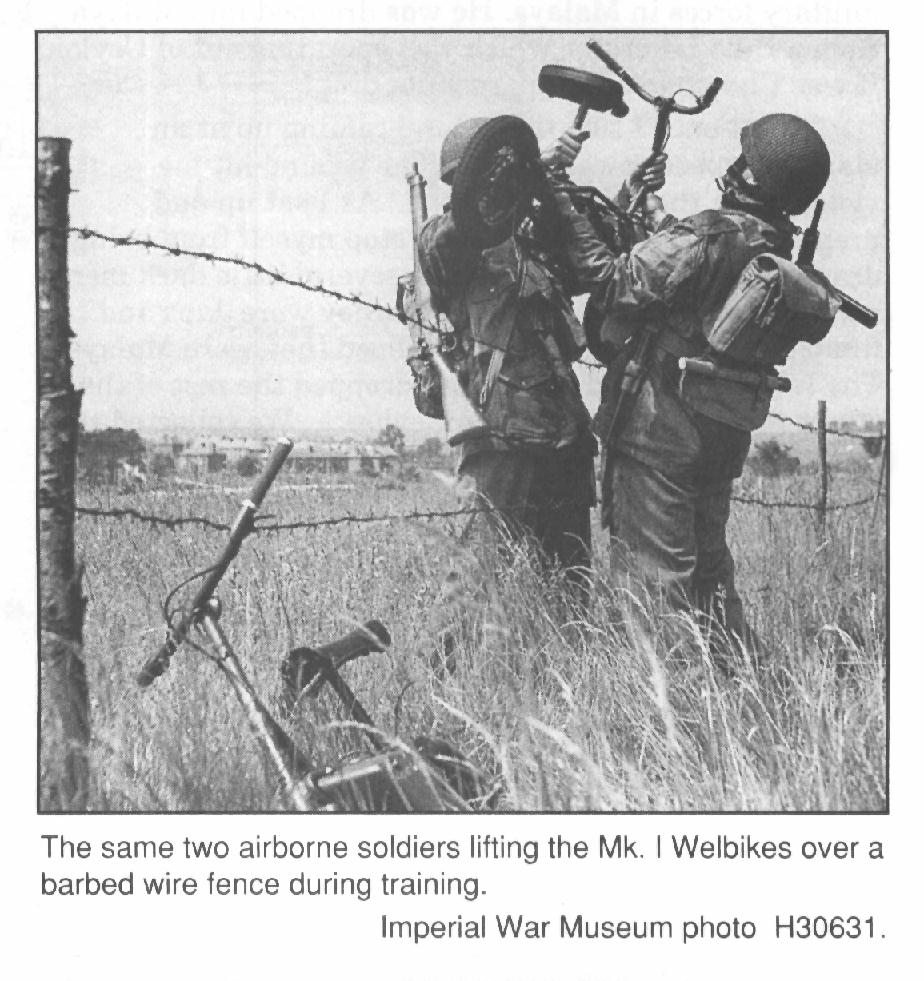

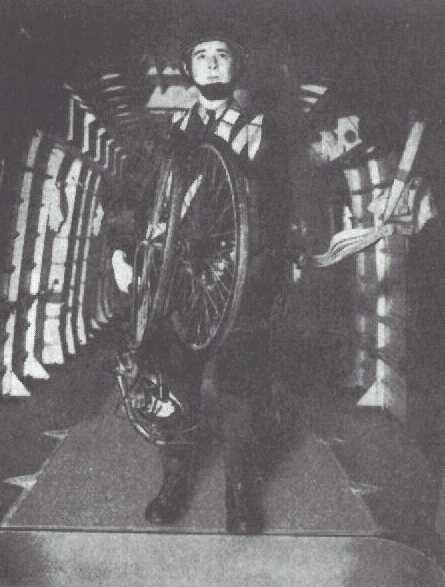

In WW2 bicycles were a cheap and lightweight method of giving mobility to infantry. This was particularly true for Airborne troops, who were obviously much more limited in the size and number of vehicles that could accompany them. The British Airborne forces had a unique bicycle designed to be folded in half and parachuted down. While somewhat bulky by today's standards, the bike is remarkably light. The bike could either be dropped separately or strapped to the parachutist. A member of the [6th Airborne re-enactors] unit has acquired and restored one of these interesting pieces.

BSA Folding Airborne Bike rigged to be dropped separately

Following are several more photos of this particular bike along with several wartime photos. All of the following text is taken from the war-time military manual for the "Type G Apparatus", the folding bicycle.

General Notes

Stores Ref. Number: The Stores Ref. Number of the parachute is 15C/84 Weight of folding bicycle: The weight of the folding bicycle and parachute is 32 1/2 lb.

It is necessary to throw the bicycle vertically downwards through the door of the aircraft to prevent the parachute fouling the tail. Tests were made by A.F.E.E. from a C-47 with satisfactory results.

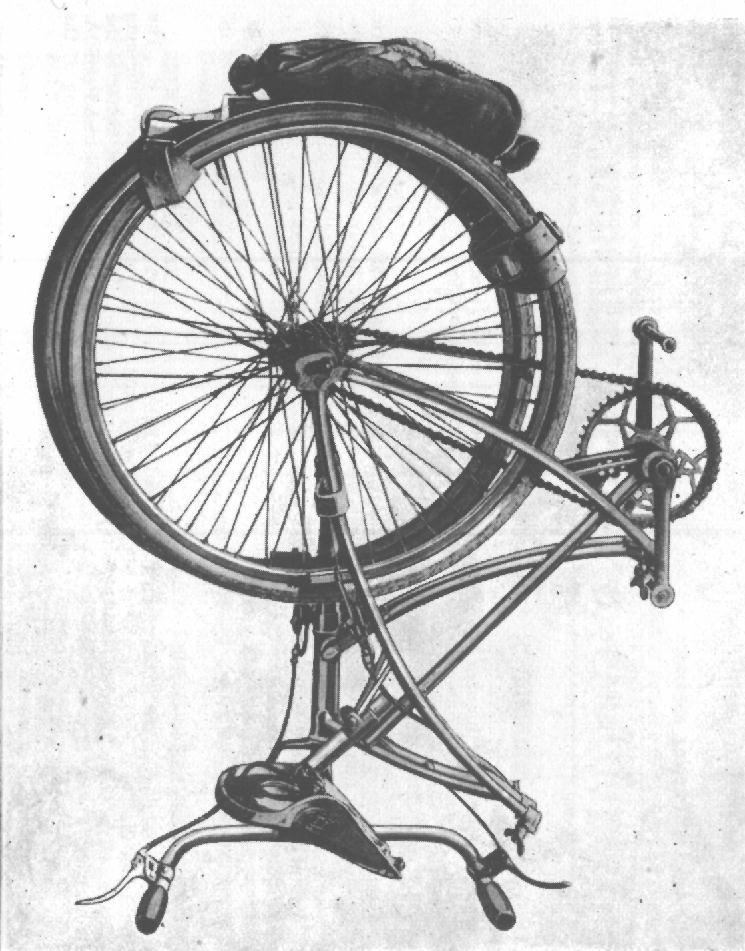

Airborne Bicycle General

The frame of the bicycle is elliptical and is hinged at two points. The slackening of two wing-nuts enables the frame to be folded so that the two wheels lie side by side. The wheels are lashed to the frame to prevent their turning and a type Q parachute with 12 ft. Canopy, as described in A.P. 1180A, Vol. I, Part 2, Sect. 2 Chap. 4, is attached to their circumference. Any partial bending of the handlebars on landing can usually be corrected by hand.

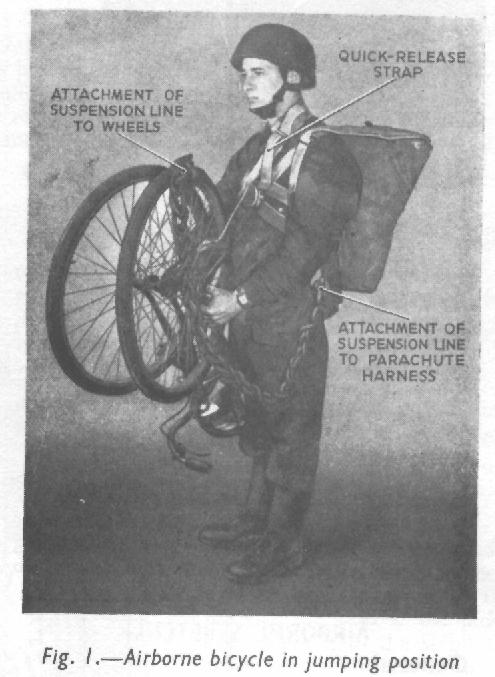

Parachuting with the Airborne bicycle from either Dakota or Stirling Aircraft is simple and requires little equipment. The bicycle is suspended from the parachutist´s body by a quick-release strap when jumping and is always released and lowered to the full extent of a 20 ft suspension line during descent.

Preparation of Bicycle

Fold the bicycle and push the pedals through into the stowed position. Lower the handlebars and raise the saddle so that the latter will receive most of the landing shock.

Strap both wheels together, securing them to the rear chain stays to prevent them from rotating (An Army-issue valise strap is most suitable for this.). Tie one end of the 20 ft. suspension line to both the wheels in such a position that when the cycle is suspended by the line the saddle is lowermost. This is important to prevent damage to the handlebars.

Method of Attaching Bicycle to Parachutist

Commencing from the free end, plait the suspension line to ensure that it will pay out quickly and easily without forming loose coils likely to foul the cycle. Take the free end and tie it to the lower left leg strap of the parachute harness. Finally, suspend the bicycle from a quick-release strap passing round the back of the parachutist´s neck.

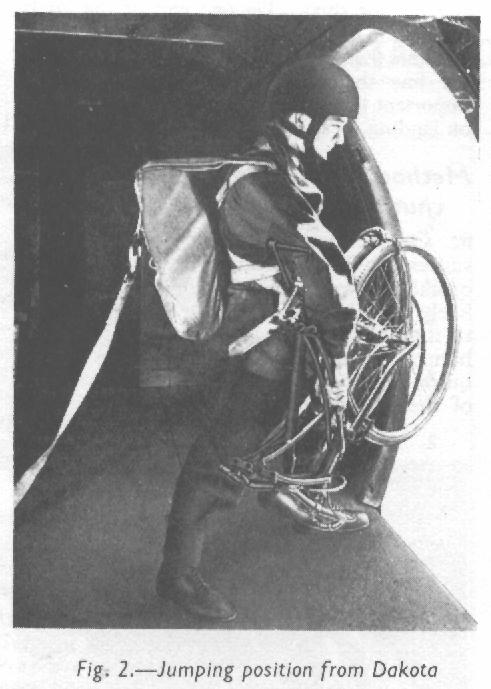

Method of Jumping with Airborne Bicycle

When making an exit from [C-47] Dakota aircraft, hold the bicycle slightly forward and to the right-hand side, as shown in fig. 2. Take care to avoid fouling the forward edge of the door and catching the brake cable of the bicycle on the door jettison handle. Step well out to avoid being brushed along the side of the aircraft. As soon as the canopy has developed, release the bicycle by pulling the loose end of the quick-release strap.

When jumping from Stirling aircraft, hold the bicycle slightly forward and to the right-hand side, as shown in fig. 3. It is important to stand slightly to the starboard side of the aircraft centre-line to prevent the cycle from fouling the exit. As soon as the canopy has developed, release the bicycle by pulling the loose end of the quick-release strap. No anti-sear sleeve is required.

Japanese bicycle-infantry conquering the Philippines

British Airborne folding bicycle

Vietnamese Bicycle Use

Bike decisive Logistical means at the Battle of Dien Bien Phu

www.youtube.com/watch?v=7k0foADqw0w&feature=related

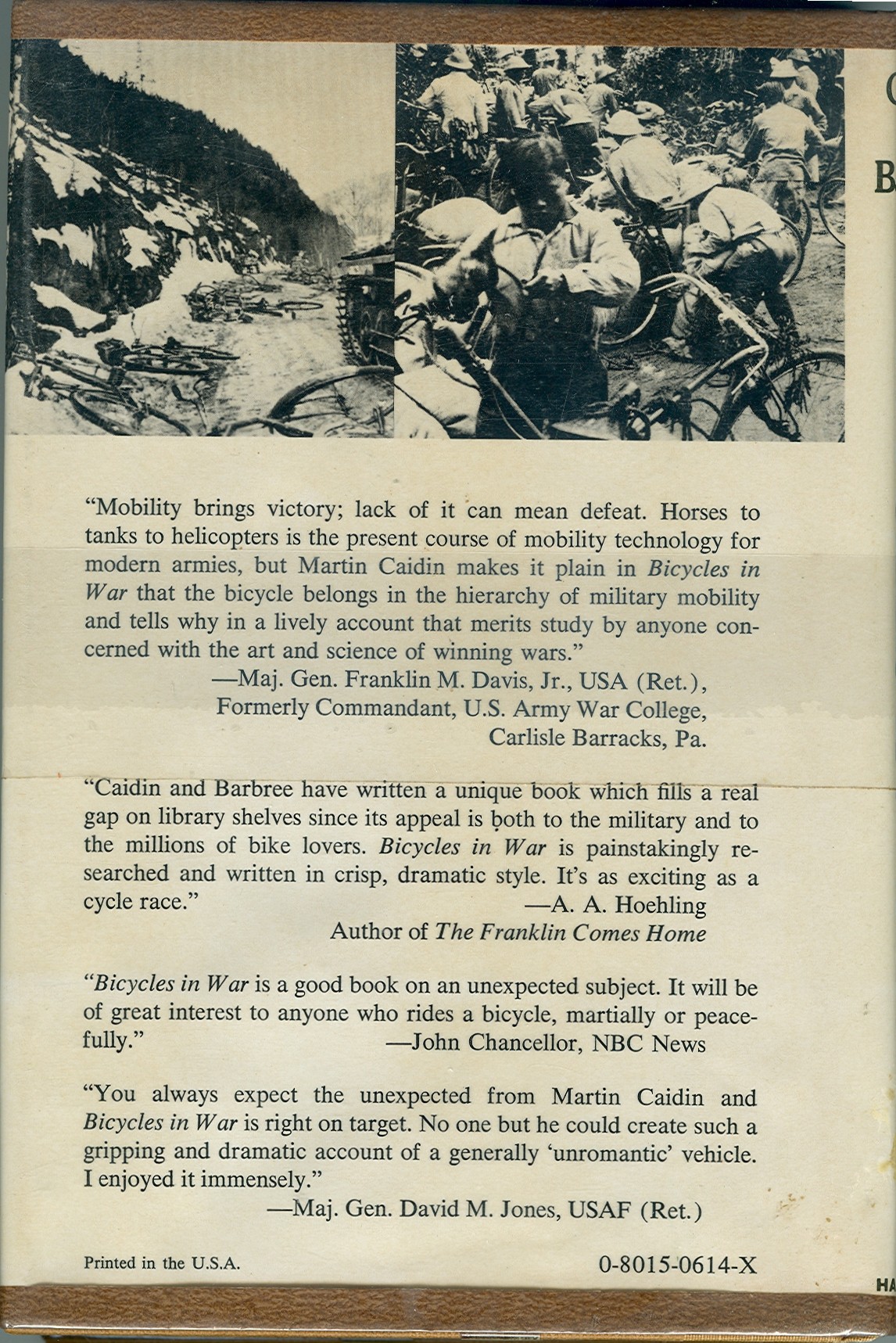

Some of the best references are Bicycles at War by Martin Caidin and Jay Barbree, 1974 (see bottom of this web page) and the 1989 U.S. Army Command & General Staff College Master's Thesis of then Major Stephen Tate: "Human Powered Vehicles in support of Light Infantry Operations", Defense Technical Information Center, AD A211 795, and Infantry magazine, September-October 1994, "Bicycle Infantry: The Swiss Experience" by CPT Kevin Stringer who was a liaison officer with the Swiss Bike troops, January-February 1995, "Airdrop of All-Terrain Bicycles" by Michael Sparks, Pages 4-5. LTC Edwin L. Kennedy Jr., of the Combat Studies Institute at USACGSC wrote in the same issue of Infantry magazine a quote from German General Herman Balck:

"From the early '30s, I advocated equipping infantry with bicycles in preference to motorcycles for the reasons that bicycles would be very quiet, would be able to go off roads onto trails, and would be almost as fast as motorcycles. However I didn't have the time or the position to fight for this position. I had some actual experience with bicycle infantry because right after the First World War, I commanded a bicycle infantry battalion in Germany...the mobility of the bicycle troops was quite good. It was absolutely no problem to make a hundred kilometers in a day..."

He then adds:

"The U.S. Army has also tested bicycles--both in the late 1800s and in this century. In a 1988 REFORGER Exercise, we used bicycles in a company that was designated one of our division's Air Assault elements proposed by Captain Kevin Stringer"

www.youtube.com/watch?v=FkjpDZ1O4C0

www.flickr.com/photos/2kings/2617570242/

armybicyclecarl says:

This MO-05 (militaer ordinanz 1905) example is from 1979 . There were numerous chainwheel designs and two head badge decals over the 83-year production run at Condor of Switzerland. 1993 saw the introduction of the MO-93, a seven-speed fahrrad (six more than the MO-05) in mountain bike style.

Swiss Bicycle Trailer/Sled for M1905 or M1993 Bicycle (?)

http://cosprings.craigslist.org/spo/873904173.html

www.flickr.com/photos/2kings/2617570242/

armybicyclecarl says:

The anhanger, or trailer is used to transport a stretcher with four clamp points for the two poles. The trailer weighs 62 pounds of steel, wood and rubber. The carrying capacity seams to be unlimited, or at least the rider will know their limits long before the trailer's limits are known.

On the way home this day, I passed a VW waiting first at the red light. Just as I passed with the bicycle, the passenger door flung outwards just as the trailer's wheel was passing. The first sign of trouble was the loud crunch. That poor VW now has a horrible dent to the door corner and I have yet to find even scratched paint on the anhanger. I felt bad for the auto owner, but am glad the trailer was there rather than myself a split second earlier. The VW passenger sure was civil and apologized for the scare. We shook hands and departed.

This is an original Swiss bike trailer for the MO-05. The trailer is basically meant to carry a person on a stretcher. Those stretcher with four terminals can be securely fastened. The folding cart is not so much space. The wheels can be removed with a quick and simple operation. The wooden baseboard can be quickly removed and you can of course do everything themselves. He is very stable behind the bicycle.

WITH ALL-TERRAIN CART/SLED

He seems quite sturdy and that is true. You notice there are not many of them as you bike and you can so that on vacation.

The cart and the bicycle are a wonderful combination.

BIKE + CART/SLED INTERFACE

Here is the trailer attached to the hook that comes.

WITH STRETCHER TO MEDEVAC A CASUALTY

Kar stretcher and with the "towing"

CART/SLED ON ITS OWN (TOWED BY HAND) an option

CART/SLED DETAILS

A wheel as you get there from.

The retracted bracket.

In the folded position he does not take much space.

SNOW SLED

Solid and very solidly made. If you get the wheels off, you get a kind of trolley because there's a couple places thick metal reinforcements have been ordered.

"Bicycle Infantry: the Swiss Experience" by Captain Kevin D. Stringer, U.S. Army Infantry magazine, September-October, 1994

Their official Swiss military web site states:

Combat effectiveness and speed: mechanized and light troops

"Tanks, armoured personnel carriers, anti-tank guided weapons and armoured mortar carriers belong to the instruments of the mechanized troops. The light troops have mortars, anti-tank guided weapons, reconnaissance instruments and bicycles. Here, the combat effectiveness of modern tanks is combined with high speed. This allows the defenders to strike well-aimed blows against an opponent who has broken into the country, and to maintain control of the terrain. Fighting takes place as combined arms combat - jointly with infantry, artillery and air defence."

Jane's Defense Review elaborates:

The Legendary British BSA Folding Bicycle

"A unique Swiss Army formation is the bicycle regiment; it can be deployed to counter threats to the corps' rear or used to secure lines of communication for the deployment of armoured brigades or other formations. It is organized into two bicycle battalions and a headquarters battalion, including a Piranha TOW company with nine vehicles. Companies have received the new Bicycle 93, a mountain bike design which allows Soldiers quick access on road or cross-country. Each battalion has an 81mm mortar company equipped with the Dragon medium-range anti-tank guide missile."

Headquarters 5 Airborne Brigade

Montgomery Lines

Aldershot, Hants GU11 2AU

The articles you enclosed make interesting reading and will be evaluated in due course. Once again many thanks for your interest."

"Thank you for your letter of the 2 Nov 93 outlining the low cost solution to our lack of mobility. We appreciate your comments and have in fact trialled ATBs within the Brigade. We have a limited number which are used on the airhead to enhance communications.

A T Boyd

Maj

for comd

British Gurkhas Bicycle Security Fence Patrols in Hong Kong

www.youtube.com/watch?v=U_vWEmZNdfI

THE SWEDES

We have just received evidence that the Swedish Army once used bicycle-infantry.

http://home.swipnet.se/~w-42039/testsida.htm

One of the armored infantry battalions became bicykle mounted. This meant that the mobility of the battalion was totally warped. Three different speeds of advance. To command this battalion effectively was not possible. In practice one half of the battalion fought together, the tank company and the KP-car mounted armored infantry company, while the tractor towed bicykle company fought with other units of the battalion.

Condor Club of Holland found the following on Wikipedia:

Condor Club of Holland found the following on Wikipedia:

The Swedish military bicycle (Swedish: militärcykel), or Swedish army bicycle, has been used in the Swedish military for over a century. In typical military humour, these were nicknamed LTGAC (Swedish: Lätt terränggående attackcykel or Light All-Terrain Attack Bike) by the conscript soldiers using them.

The first bicycles in the Swedish military were privately owned or bought for testing purposes. Bicycle infantry were first introduced in 1901, when a Gotlandic infantry regiment, I 27 in Visby, replaced its cavalry complement with bicycle-mounted troops. By 1942, there were six bicycle infantry regiments in the Swedish army, operating mainly m/30s and m/42s. However, there were also examples of undesignated tandem bicycles for use by field radio operators and specially fitted pairs of bicycles designed for mounting a stretcher between lead's rack and the rear's steer tube.

Following World War II, in 1947, the decision was made to decommission the bicycle infantry regiments. They were gradually removed from the Army between 1948 and 1952. Following this decision, the role of the bicycle shifted away from a combat one to a more utilitarian one, with special bicycle transport groups being formed. However, bicycle rifle battalions (Swedish: cykelskyttebataljon) continued to exist into the late 1980s.

m/1901: A safety bicycle, it was the first officially designated bicycle in the Swedish army

m/30: A spoon brake equipped, balloon-tired roadster. It was based around an agreement with several large Swedish manufacturers regarding the interchangeability of parts. Weight: ca. 23.5 kg (52 lb.)

m/finsk: A Nymans-manufactured bicycle without chainguard. The label finsk is the Swedish word for Finnish.

m/42: The most well-known Swedish military bicycle. It was produced by several large Swedish bicycle manufacturers (Rex, Husqvarna, Monark, Nymans) from the 1940s to the 1950s with a maximum of interchangeable parts. It uses a rear, one-speed Novo coaster brake hub and, on Husqvarna-produced examples, a front drum brake (chain-operated by an integrated right-hand lever). In addition, it has a large, sturdy rack with a tool box and storage tube for a short frame pump. Weight: up to 26 kg (57 lb.)

m/104, m/104A: 26 × 11/2 inch (584 mm) wheels with Sachs Torpedo rear hub.

m/105, m/105A: Post-1971. 28 inch wheel with Sachs Torpedo rear hub.

m/111

Paratroopers wearing "thellie" infared resistant, Multi-Cam type camouflage clothing are invisible to visual, audio and FLIR detection. Couple this invisibility with A/ETB mobility and you have a battle-winning combination that can be taken along with Paratroopers during their jump into the drop zone.

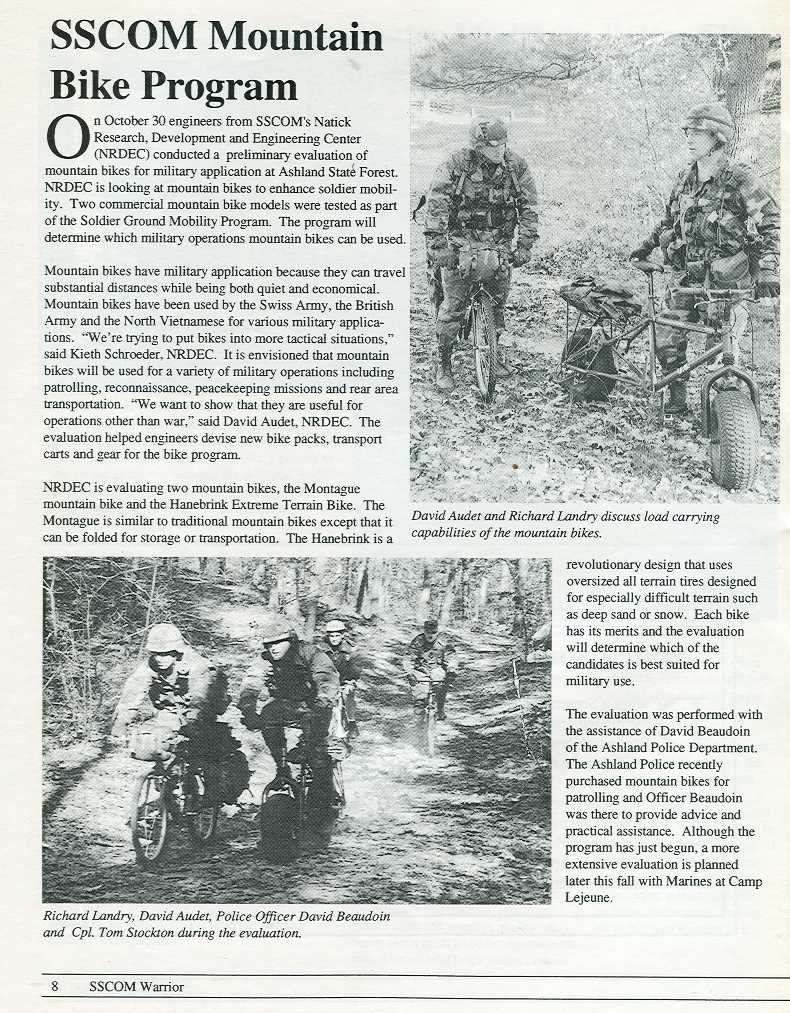

Thanks to the efforts of the 1st TSG (A) which contacted the U.S. Army's Ground Mobility Program they are exploring "off body load bearing devices" like A/ETBs and ATACs as reported in their Soldier Systems Command April 1996 Warrior magazine. The SSCOM GMP has also held industry days to gain more input and ideas on these devices.

BIKES AND SPECIAL OPERATIONS....

Anyone who has seen the film, "Blackhawk Down!" will note that in 1993, shortly after the 1st TSG (A) test jumps that U.S. Army Special Forces Operational Detachment Delta ("Delta Force") used a mountain bike to infiltrate and exfiltrate an operator into and out of downtown Mogadishu, Somalia to gain intel on the whereabouts of warlord Muhammad Farrar Aideed. The film shows the Delta operator with All-Terrain Bike in civilian clothes being picked up at a beach landing site by a MH-60K helicopter.

Retired Command Sergeant Major Eric Haney in his superb book, Inside Delta Force on page 210 notes:

"For our part, we shot targets, blew things up, and executed building assaults. We also made free-fall parachute jumps with motorcycles and, upon landing, roared past the VIP stands firing our submachine guns".

Therefore, if Delta Force can put out heavy motorcycles under a parachute canopy and follow them in under their own parachutes, land together and ride motorcycles, certainly smaller A/ETBs can be airdropped and utilized in a similar manner where more stealth is required.

Its also common knowledge the multi-billion-dollar Osprey tilt-rotor aircraft is too small to carry even a HMMWV inside and this is a major handicap, forcing SF units to fight at a foot-slog. A/ETBs can be cycled and rolled right off the rear ramp of helicopters/tilt-rotor aircraft so SF units can perform special operations with 10-25 mph mobility----not getting surrounded and decisively engaged as famed SAS patrol "Bravo Two-Zero" was in Iraq.

FORCE MULTIPLIERS....

In Vietnam, U.S. Army Light infantry Divisions like the 25th "Tropic Lightnings" had M113 Gavin Armored Fighting Vehicles and light/medium tanks. Today, out of spite and jealousy, senior Army officers have blocked repeatedly our light units from getting tracked light tanks like the M8 Armored Gun System to replace the retired M551 Sheridan or even modernized M113A3s out of fear that these units will get all the "action" and have nothing left for the heavy units to do to put on career resumes. Thus, we are stuck with trying to airland heavy 70-ton Abrams tanks and 33-ton Bradley Fighting Vehicles 4 hours after Paratroopers have jumped/died to seize a concrete runway for them to airland. This heavy force structure is too slow to deploy by air to take down a Kosovo so we ended up bombing 2 million people into refugee status before the enemy gave up after we decided to mass for a ground invasion. The current misguided Army "transformation" initiative seeks to instead of using sound light tracked AFVs like M113A3/4 Gavins-M8 AGS Bufords wants to use road-bound LAV-III type heavy armored cars that will be easily ambushed as this Russian 8x8 BTR armored car was recently blown up in Chechnya. To add insult to injury, only 2 x LAV-IIIs can be flown per C-17--the same number as M2 BFVs that can fly in a single C-17 sortie, and neither can fly by C-130 because the LAV-III is too wide, and at 16.5 tons EMPTY exceeds the USAF's 16-ton forward landing strip limit! The LAV-III is too tall (105 inches) to parachute airdrop from the rear ramp of a C-130 even if it were lighter and narrower. What we need are mobile Airborne/Light Divisions coupled with light Armored Fighting Vehicles (AFVs) like the 10.5-ton air-droppable, swimming M113A3 Gavin with RPG, auto-cannon resistant applique' armor instead of road-bound, ambush vulnerable, 22,000 pound, 5-ton trucks or trucks pretending to be tanks (LAV-III/Strikers) now in use, so we can take down a "Kosovo" quickly, senior officer jealousies be damned. With light AFVs like the M113A3, the U.S. Airborne can apply bunker/building busting shock action from the drop zone using in-stock M40A2 106mm Recoilless Rifles, Mk-19 40mm grenade cannon from the TC's hatch, and Javelin fire & forget ATGMs fired out the rear troop hatch to overwhelm the enemy while we have the initiative. The Airborne Assault Echelon with light tracked AFVs can overcome enemy fires to secure the drop zone to enable it to be an assault landing zone for follow-on forces to airland. ATB-equipped LBI forces would drop away from enemy defenses and fan out to set-up blocking positions and establish the recon & security zone to act as a covering force to keep the enemy at bay and out of mortar/artillery range as the airhead builds up. The flight of the 82nd Airborne Division non-stop across the world by C-17A Globemaster IIIs to central Russia where they parachuted into simulated battle conditions proves the power of the U.S. Airborne......See photo below....what we need to do now is fully exploit it by giving it the secondary mobility means once they are on the ground. Beginning with LBI and "Dragoons" in ATVs, and M113A3 AFVs is a very low-cost way to create these capabilities NOW, before there is another Kosovo-type crisis. 100% of the air is covered by AIR and vulnerable to AIRBORNE attack....while a tiny fraction borders on watery edges. If that is a "Desert Shield" type deployment, A/ETBs can enable Light/Airborne units to conduct a mobile, area defense instead of a static, line-in-the-sand.

We have been to NTC as OPFOR and we won. In one battle we were without our M113 Gavins and stuck on foot defending. ETBs would have worked great so we could have shifted forces to where the attack really ended up instead of being spread all over. We could have been on the reverse slope and used them to rapidly move to firing positions on signal. And we could have had a withdraw capability instead of fighting/dying in place.

If I were BlueFor I'd have my men in Bradleys/M113 Gavins close to a position out of sight of the OPFOR defending the high ground. Then, at night close rapidly through a smoke screen (made by M58s--M113s with smoke generators--or artillery barrage in actual war) by ETBs to the defenders position and take the key terrain BEFORE trying to stampede AFVs which only gets everyone killed as the pass gets clogged with dead vehicles. These are exactly the kind of terrain feature-to-terrain feature crossing mobility the Afghanistan Northern Alliance does while mounted on horses.

UPDATE 2002: Afghanistan: where all-terrain mobility is a MUST. Easily ambushed roads must be avoided

1. Mules to transport long-range rockets/mortars for infantry raids

The Bear Trap

afghanbooks.com

Special Forces Mounted Operations

FM 31-27, PACK ANIMALS IN SUPPORT OF ARMY SPECIAL OPERATIONS FORCES, 15 FEB 2000

https://hosta.atsc.eustis.army.mil/cgi-bin/atdl.dll/fm/31-27/toc.htm

2. Video footage of bikes/carts

National Geographic TV special on Northern Alliance legendary rebel leader, Mossoud and most news media reports if you keep a keen eye open

3. Horse Cavalry that attacks from terrain feature to terrain feature

Ah, that we would open our minds to off-road mobility, including forces using armored TRACKED vehicles flown in by aircraft to then maneuver to compliment the lighter forces on foot, bike, cart, mules, horses, ATVs etc.

Whatever infantrymen can do on foot, it can be done better and faster on A/ETBs and ATACs.

UPDATE 2004: PROGRESS

Amphibious Light Bicycle Infantry

The centerpiece of a good light bicycle infantry should be a M113 Gavin light tracked AFV to provide large distance mobility, armor protection, battery recharging, supply carry, overwatching sensors and fire support. M113 Gavins can swim in lakes/rivers and with waterjets, oceans.

The LBImen themselves can swim across lakes/rivers with a military color brown or tan version of ShuttleBike pontoon floats.

www.shuttlebikeusa.com www.gizmo.com.au/public/News/news.asp?articleid=2530

When you consider that the LBIman has an ability to parachute insert and helicopter insert/extract, being able to swim adds an extra dimension for scouts fanning out from their "mother" M113 Gavin.

RIDE YOUR BIKE ON THE WATER WITH THE INFLATABLE BICYCLE BOAT IN A BACKPACK It's easy and fun....set up in 10-15 minutes....up to 6 miles per hour....

Aluminum alloy frame clamps attach to your bicycle The entire Shuttle-Bike Kit in a backpack!

Propeller and rudder Easy and quick float inflation with pedal power

SHUTTLE-BIKING IS THE ULTIMATE PEDAL-POWERED EXPERIENCE!

Shuttle-Bike Kit Features and Technical Information:

Aluminum alloy frame clamps attach as a permanent accessory to your bike.

Stainless steel snap-together bike support frame.

Brushed aluminum alloy propeller gear housing.

Propeller/rudder combination attaches to front wheel - steer with your handlebars.

Clutch pivot retracts propeller in shallow water.

Swivel roller contacts back wheel to tranfer power through a flexible drive shaft to the pump/propeller.

275 pound maximum safe load (450 lb. emergency rescue).

4 miles per hour cruising, 6 miles per hour maximum speed.

Pedal powered rapid inflation pump with pressure relief valve.

Dual floats make the Shuttle-Bike(r) more stable than canoes, kayaks and other monohulls.

Highly maneuverable - can turn 360 degrees in place.

Compact - everything fits in a 25 lb. packpack.

No tools required for quick setup on the shore.

Economical - lowest priced pedal powered watercraft available.

Precision machined mechanical components - fine craftsmanship.

The Shuttle-Bike Kit is made in Italy by SBK Engineering.

SHUTTLE-BIKE USA, Inc. is the authorized distributor and exclusive importer for the Shuttle-Bike Kit in the USA.

Toll Free USA Order Line: 1-877-725-2329.

Information Line: 1-425-823-7763.

Most major credit cards accepted. Dealer inquiries welcome.

Email address: shuttlebikeusa@aol.com

Mailing address: 9805 NE 116th St. #7139, Kirkland, WA 98034

Stability and Support Operations (SASO) in Iraq

1. American infantry squad leaves fortified base camp in up-armored M113A3 Gavin with gunshields to city/town/village area. If enemy explodes bombs and/or ambushes by RPGs, small-arms fire troops will survive initial volley and be able to fight back.

2. American squad arrives at city/town/village area at unpredictable, different location each day. Infantry dismounts from M113A3 Gavin and re-mount onto all Terrain "MounTain" Bikes (MTB)s taken off the Gavin's sides where they were snap-linked. Squad fans out into two fireteams, left and right of road with M113A3 Gavin and at least one if not 3 machine gunners riding "shotgun" with overwatching fires if enemy should ambush.

3. Cycle troops are wearing FULL Interceptor Hard Body Armor and kevlar helmets with clear ballistic face shields to protect in event of grenade/small arms/bomb attack. Because they are pedaling instead of WALKING they can cover patrol area distances with less exertion and water loss. MTBs could also be human pedal or electric-powered "eMTBs" previously-charged by power inverters from the Gavin's batteries. Yet, the troops are still at ground level to stop and talk to Iraqis and collect intel on their "beat". The question is in a situation of quasi-peace how much more vulnerable are the troops riding and stopping on ATBs with weapons slung at the ready in the same way as they are on foot movement if they can cover larger areas and gain more preventative intel? If the troops can cover larger areas wouldn't this contribute more to their safety than the slight advantage having one hand on the M4/M16/M249 weapon's pistol grip instead of on a handlebar. The point is that troops wearing IBA are due to weight not patrolling as aggressively on foot and covering as large areas as the British are in the south without hard body armor to control and influence their "beat". MTB or eMTBs.

4. Patrol complete, the troops rally onto their "mother" M113A3 Gavin and snap-link their MTBs to the vehicle's sides, remount inside the Gavin weapons facing out through the top troop hatch. Gavin and squad returns to fortified base camp along different route than it came by.

5. Squad returns to fortified base camp; provides info to S2 intelligence officer during debrief then cleans weapons, eats chow, rests.

6. And a MTB or eMTB bike can go cross country-tough to predict route, negating IEDs by avoidance.

7. Tweaks

A British Army officer writes:

"Interesting. The UK issued bikes for boarder road patrols in Hong Kong. - Never spoke to anyone who did it, but it seemed to work chasing 14 year old Chinese kids!

As I see it, the concept has three prime equipment components.

1.. M-113A4

2.. MTB

3.. Body armour

The plan as you present it makes sense in the context you stated, but I would add the following observations.

1.. Would bike borne troops be more or less vulnerable to small arms fire and blast from IED?

2.. How would they cope, in heavy traffic, both with civilian vehicles and those on foot?

3.. To patrol in the IS environment, you are constantly stopping and talking to people, going into shops, stopping vehicles and just holding firm, to await the start of your next phase.

4.. No Squad/Section EVER patrols alone. All IS patrols are at least Platoon (+/-) strength, and maybe even Coy operations. Movement is always on multiple routes, aimed at the manoeuvre defeat of the bomber or shooter, PRIOR to his engagement. - In very simple terms, this is why the IRA gave up sniping in city centres. It was just too dangerous for them.

5.. Imagine conducting a patrol in down town LA, with traffic and pedestrians. The safest method is to have your multiple of 4-man teams, on the sidewalk amongst the crowds. - watch how the Israelis do it. The enemy have to try and track lots of teams snaking around the area.

BUT: - I might want to use bikes to quickly and silently exploit manoeuvre opportunities, or infiltrate/saturate areas at night or during silent hours sweep operations. - I'd have 3 x 4 man teams on foot, and 2 x 4 man teams on bikes. Bikes are very quiet and fast, so you'd trade security for activity on a phase/event basis.

The bike men would be dismounted most of the time, and only mount and dash, to leap frog forward, when required.

Like wise, you could foot patrol a small amount of teams into an area, that once they had secured it, could be rapidly flooded by a Coy on bikes, to conduct sweeps or searches. - no warning sounds of Hummvees of AFV's in the night.

End of OP, M-113's come in to extract everyone, plus the bikes."

Good points! We add that LBI troops should carry a very large padlock to clip to a light pole to secure their bikes if they decide to apprehend someone on foot.

BICYCLE-INFANTRY AS THE CENTERPIECE OF A FUTURE FORCE DESIGN

Noted defense reformer and theorist William S. Lind proposes a bicycle-infantry centric redesign of the USMC in marine corps Gazette:

www.mca-marines.org/Gazette/2003/03Lind.html

EXCERPT:

"The basic unit of the Islandian marine corps is the infantry battalion. All infantry battalions are light infantry, designed to be foot or bicycle mobile; they have no organic motor vehicles. Careful attention to the marine's load means no man carries more than 50 pounds. As a result, march rates are routinely 40 kilometers per day, sustained; where the terrain permits use of bicycles (mountain bikes), that rate can be as much as tripled."

An Army Captain writes:

"Interesting concept.

I'd rather we start placing static patrols into OPs at really good spots for reconnaissance and ambush to catch the bad guys with their hands in the cookie jar.

Use the a fire team hide position similar to what the Brits devised in N. Ireland. Equip with thermals, digital cameras, etc.

Dig them in at night for maximum concealment and go "silent" for about a week. Track the comings and goings. Then move when they have a juicy target."

A former USAF Combat Control Team (CCT) member and professional bicyclist writes:

"It sounds feasible. Is all of that body armor required equipment for these troops? My thoughts tend to lean more towards the "travel light, freeze at night" SUT mode because of my CCT background.

Bicycle handling is effected greatly by weight and it would seem that tight manuevering to get either into, or out of a situation (especially urban) would be paramount in reference to individual, or squad mobility.

The only way I could make a truly informed decision would be to gear-up and get on the bicycle(s) to be used and ride. Of course, it would have to include live fire exercises..."

NEW ATBs!